Latest News

-

Landmarks Scholarship Reception Celebrates Community-Minded Young People

David Brashear, chairman of our Landmarks Scholarship Committee paused with scholarship and honorable mention winners at a reception held in the Grand Concourse restaurant. From top left: Maclaen Johnson, David Brashear (standing center), Clark McCord. From bottom left: Desirae Nance, Madeline Douglas, Negein Immen, Mia Schubert

David Brashear, chairman of our organization’s Landmarks Scholarship Committee presented winners of three scholarships and 11 honorable mention award recipients at a reception held at the Grand Concourse restaurant in Station Square on June 27.

The financial award for our scholarship is $6000 paid directly to the recipient’s account at the college or university of their choice. The scholarship winners include:

- Maclaen Johnson, is a graduate of Bishop Canevin High School and a Junior Councilperson of Carnegie Borough. He will study History and Political Science at the University of Notre Dame.

- Clark McCord, a graduate of Central Catholic High School, will pursue Civil Engineering and Architectural Studies at the University of Pittsburgh.

- Luke Smarra, is a graduate of Montour High School and will study Economics and Art History at Tulane University.

Eleven students received $250 as a one-time honorable mention award, which will also be paid directly to their accounts at their college or university of choice. Honorable mention recipients include:

- Madeline Douglas a graduate of Woodland Hills High School will study biomedical engineering at Columbia University.

- Negein Immen a graduate of Pine Richland High School will study Civil Engineering at Penn State University.

- Desirae Nance, a graduate of Sewickley Academy will study Chemical Engineering at Hampton University.

- Mia Schubert, a graduate of Shaler Area High School, will stud Biology and Business at Juniata College.

- Aubree Arelt, a graduate of Serra Catholic High School, will study Economics at West Virginia University.

- Christian Cropper, a graduate of Eden Christian Academy, will study business at Hope College.

- Christian Duckworth, a graduate of North Allegheny Senior High School, will study Architecture at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

- Madison Martin, a graduate of Sewickley Academy, will study Psychology at New York University.

- Elizabeth Neel, a graduate of Pittsburgh CAPA will study Early Education at Temple University

- Hailey Shevitz, a graduate of Pittsburgh Allderdice will study International Relations at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Melaina Thompson, a graduate of Pittsburgh CAPA will study Art at Cornell University.

Since 1999, our organization’s Scholarship Committee has awarded 85 scholarships, payable over four years, and 51 honorable mentions, a one-time gift. In doing so, we have connected with 136 high-achieving, community-minded young people who care deeply about the Pittsburgh region and recognize the value of historic preservation.

This program is funded by the Brashear Family Fund, Scholarship Committee members, and the Landmarks Scholarship Fund, including donations to the 2008 and 2014 Scholarship Celebrations. We thank each donor for supporting this program that helps young people achieve their educational goals and stay connected to the Pittsburgh region through our organization.

-

Three Winners and Eleven Honorable Mention to Receive Landmarks Scholarship

Maclaen Johnson, one of the 2022 Landmarks Scholarship winners, wrote about the Andrew Carnegie Free Library & Music Hall in Carnegie, PA. By sixth grade, he was volunteering at the library. He wrote: “I developed self-confidence and enriched my knowledge of history inside the storied structure.” The Carnegie Carnegie, as the building is now called, recently dedicated a beautifully landscaped Library Park.

“It’s a remarkable achievement,” said PHLF Trustee David Brashear. “Since 1999, PHLF has awarded 85 scholarships and 51 honorable mentions to high school graduates from Allegheny County who care deeply about the Pittsburgh region and are pursuing an undergraduate degree at a college or university of their choice.”

Mr. Brashear’s family initiated the Landmarks Scholarship Program in 1999 through a Donor-Advised Fund at PHLF. Foundations, businesses, and many PHLF members have generously contributed since then. The scholarship award of $6,000 is payable over four years to the recipient’s college/university to help pay tuition and book expenses; the honorable mention award is a one-time gift of $250, payable to the recipient’s college/university.

The following people were awarded scholarships at the May 16 Committee meeting:

- Maclaen Johnson (Bishop Canevin High School/University of Notre Dame);

- Clark McCord (Central Catholic High School/University of Pittsburgh)

- Luke Smarra (Montour High School/Tulane University).

The following were awarded honorable mentions:

- Aubree Arelt (Serra Catholic High School/West Virginia University);

- Christian Cropper (Eden Christian Academy/Hope College);

- Madeline Douglas (Woodland Hills High School/Columbia University);

- Christian Duckworth (North Allegheny Senior High School/Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute);

- Negein Immen (Pine Richland High School/Penn State University);

- Madison Martin (Sewickley Academy/New York University);

- Desirae Nance (Sewickley Academy/Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University);

- Elizabeth Neel (Pittsburgh CAPA/Temple University);

- Mia Schubert (Shaler Area High School/Juniata College);

- Hailey Shevitz (Pittsburgh Allderdice/University of Wisconsin-Madison); and

- Melaina Thompson (Pittsburgh CAPA/Cornell University).

The recipients will be recognized during a reception in June at the Grand Concourse restaurant in Station Square.

The Scholarship Program has helped introduce young people to the work and mission of PHLF and has created a network of support and a sense of family among the recipients. Two former scholarship recipients are now trustees of PHLF––Todd Wilson and Kezia Ellison––and many others contribute their time and expertise as members.

Applicants are asked to write about a place in Allegheny County that is meaningful to them. The essays this year were outstanding and insightful. Featured places included the Allegheny Observatory, Andrew Carnegie Free Library & Music Hall, Benedum Center for the Performing Arts, Cathedral of Learning, Carnegie Museum of National History & Art, First English Evangelical Lutheran Church, Fort Pitt Museum, Freedom Corner, Frick Park, Fulton Log House, Hartwood Acres, Homestead Grays Bridge, Sarah Heinz House, Kennywood Park, Sue Murray Swimming Pool, North Park, South Park, Washington’s Landing, and White Oak Park.

PHLF welcomes contributions in support of the Landmarks Scholarship Program which will be celebrating its 25th anniversary in 2023.

Please click here to contribute; be sure to designate your gift to “Scholarship.”

Thank you!

-

PHLF Supports National Opera House in Restoration of Historic Homewood House

This Queen Anne-style house in Homewood once housed the National Negro Opera Company considered to have been the first African American opera ensemble in the United States.

The Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation is pleased to support Jonnet Solomon, executive director of the National Opera House, to restore the Queen Anne-style house in the Homewood neighborhood of Pittsburgh, which once housed the National Negro Opera Company, considered to have been the first African American opera ensemble in the United States.

“We have a great partnership with PHLF, which has been essential in understanding the scale of the restoration effort we are undertaking,” Ms. Solomon said. “I have been working on this house for more than 20 years and I am pleased to have the support of PHLF, not only on advocacy but in understanding the feasibility of restoration and how to execute a fundraising plan.”

In 2008, our organization supported the house’s designation as a City Historic Landmark. In addition to offering public support for the National Opera House, we have been working to conceptualize new ideas that would move forward the restoration of the house at 7101 Apple Street.

“PHLF has taken the lead and is underwriting the cost of the civil engineering work for the site, which entails the restoration of two historic stone walls that support the structure of the house, and also includes stormwater and erosion mitigation, and landscaping of the steep hillside on which the house is located,” said PHLF President Michael Sriprasert.

“Through this partnership, we have a great opportunity to restore this important house,” said Mr. Sriprasert. “We hope that this historic preservation effort will help create and leverage more funding opportunities for community renewal in this part of our city.”

Built in 1894, the house is a landmark in American history, and not only reflects the complicated history of race in this country, but also the aspirations of African Americans who dreamed of developing and pursuing their love of music, opera, and the performing arts, in this house seated on a hill in Homewood, in Pittsburgh’s East End.

In 1930, the house was purchased by William “Woogie” Harris, Pittsburgh’s first black millionaire and brother to famous photographer Teenie Harris. As the Harris’ family home, the house hosted some of the most famous personalities of African American society, arts, sports, and culture. During a period of discriminatory housing, lodging laws, and practices, the house provided a safe place, community, and accommodations to African American artists and athletes.

The National Negro Opera Company, organized under the direction of Mary Cardwell Dawson, rented the third floor of the house, using it as offices and rehearsal space. The company lasted from 1941 to 1962 and saw productions launched in Homewood and performed in Washington D.C., Chicago, and New York, among other places.

Because of its significance, the house received a historical marker from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in 1994 and it is included in African American Historic Sites Survey of Allegheny County, published by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in 1994, and in A Legacy in Bricks and Mortar: African-American Landmarks in Allegheny County, published by our organization in 1995.

Our organization is currently designing an oral history and education program about the significance of the house as a part of Pittsburgh and American history named, A Legacy in Stone: Homewood’s National Negro Opera House and the Confluence of Pittsburgh’s African American Culture.

This project, which is funded through a grant from the African American Civil Rights Grant Program through the Historic Preservation Fund administered by the National Park Service, will also include our nomination of the house for listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

-

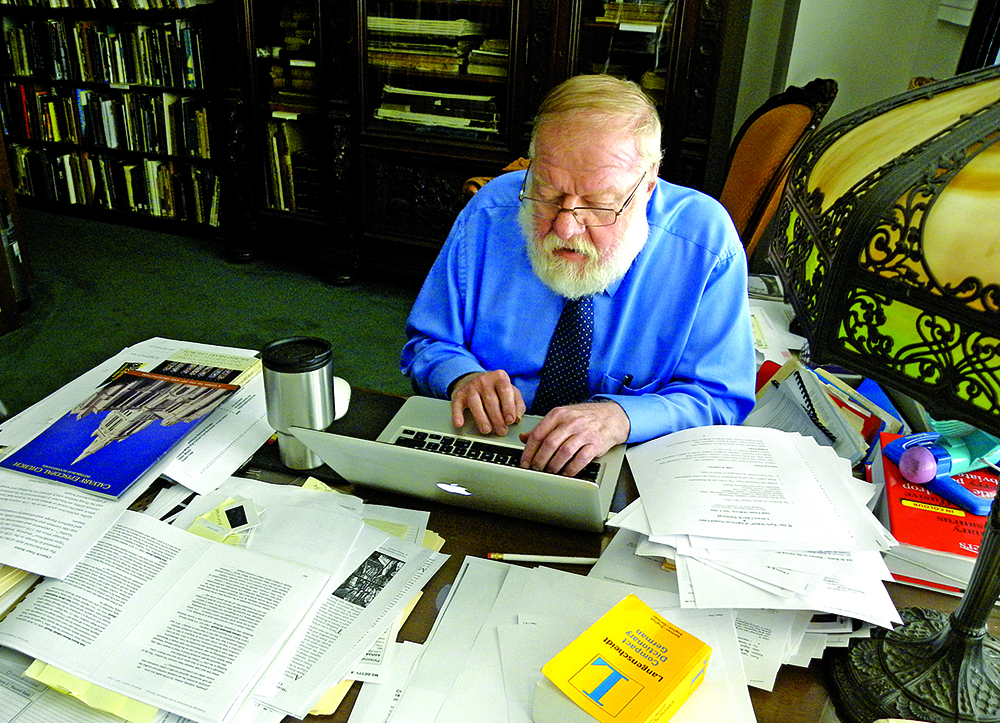

Remembering Albert Tannler, PHLF’s Longtime Archivist and Architectural Historian

Albert ‘Al’ Tannler, an architectural historian and author of significant books on the history and architectural heritage of Pittsburgh, died at St. Clair Hospital on February 24. He was 81.

A consummate researcher, editor, and archivist, Al was the director of the historical collections for the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation for 28 years, overseeing two libraries in addition to his scholarly interests.

For many years, he profiled more than 120 architects whose work defined the architectural landscape of our city and region through his writing, lectures, and specialized tours. He joined our organization in 1991and retired in 2019.

In that time, he authored and co-authored books, guidebooks, pamphlets, and many essays on various aspects of the built environment. His articles appeared regularly in the Pittsburgh Tribune Review’s Focus section from 1994 to 2004.

His Pittsburgh Architecture in the Twentieth Century: Notable Modern Buildings and Their Architects, was published by PHLF in 2013, and is the first guidebook devoted solely to the twentieth-century buildings in the Pittsburgh area.

Al was also the author of Charles J. Connick: His Education and His Windows in and near Pittsburgh, which he wrote after more than a decade of research into architectural glass and the discovery that buildings in Pittsburgh had some of the most inspired glass to be found anywhere. Published by PHLF, the book was selected by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette selected one of the best books of 2008.

Al was incredibly fascinated by the lives and stories of the architects and their clients, who built America, and the significance of their work in establishing an aesthetic that continues to define and impact how we appreciate the built environment. He established meaningful connections with architectural scholars and organizations in Pittsburgh, throughout the United States, and overseas.

In a tribute to Al upon his retirement, Peter Cormack, the distinguished British author, and expert on stained glass noted that Al’s “meticulous research, always so liberally shared with others,” and his devotion to the built heritage, truly made him “Pittsburgh’s priceless Civic Treasure.”

Al also authored a guidebook on H.H. Richardson’s Allegheny County Courthouse and Jail, published by PHLF in 2016, and he served as a co-editor of several other architectural guidebooks and publications.

In addition to his scholarly work, Al distinguished himself as a tour guide who relished the prospect of helping visitors appreciate the exceptional quality of Pittsburgh’s historic built environment. Over the years, he gave tours for assorted groups and organizations including the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Heinz Architectural Center, Friends of the Gamble House, the American Museum and Gardens in Britain, and the Society of Architectural Historians, Chicago Chapter, among many others.

A native of northeastern Pennsylvania, Al received Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Divinity degrees at Franklin & Marshall College (Lancaster, Pennsylvania) and the University of Chicago, respectively.

He lived in Chicago for more than 25 years, working as an archive research specialist for the University of Chicago Library and as a proposal coordinator in the marketing department of Sargent & Lundy, an architecture and engineering services firm, before moving to Pittsburgh in 1991.

Al’s extensive work in documenting our region’s architectural heritage will be accessible to the public through our organization’s James D. Van Trump Library, where we are in the process of creating the Albert M. Tannler Collection.

Our organization is establishing the Al Tannler Memorial Fund to underwrite various preservation efforts in memory of him. Click here to donate to this fund. Mark your contribution in memory of Al Tannler.

You may also send a check to PHLF marked in memory of Al or contact Karamagi Rujumba: karamagi@phlf.org or 412-471-5808 ext. 547 for more information on ways to support this fund.

-

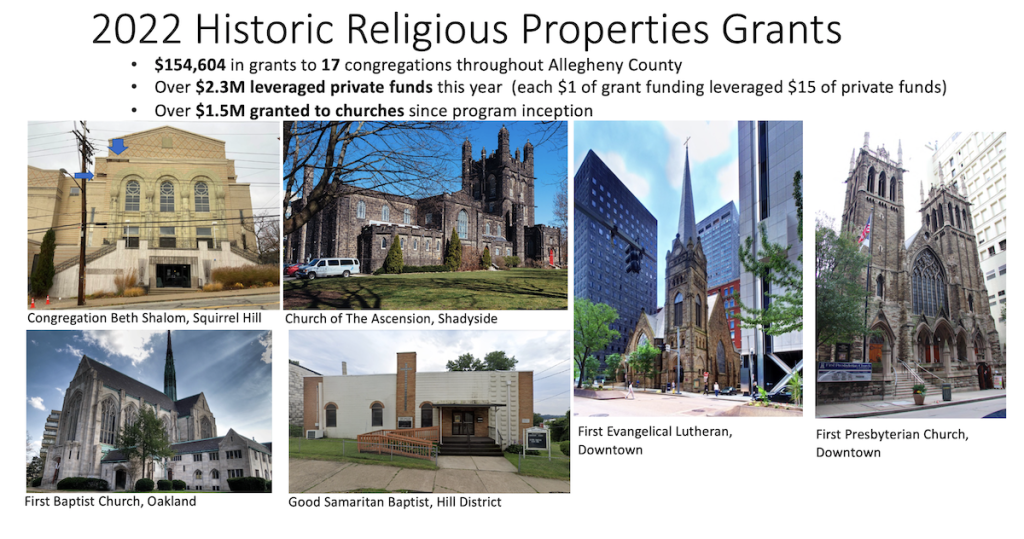

PHLF Awards $154, 604 for Renovation of Historic Religious Structures

The Historic Religious Properties Grant Program of PHLF has awarded a total of $154,604 in matching grants to 17 congregations in Allegheny County as part of its 2022 funding cycle.

The monies, which will leverage over $2.3 million raised by the congregations, will be used to fund restoration, renovation, and maintenance projects on the historic structures utilized by religious organizations. The work ranges from cornice repair to masonry, roof, wooden doors, stained glass, and stone masonry repairs, among other needs.

PHLF is the only nonprofit organization in Allegheny County offering a continuing program of financial and technical assistance to historic religious property owners. Since 1997, we have awarded more than 270 such grants totaling more than $1.5 million and provided more than 60 technical assistance consultations.

Our effort is made possible through individual donations, private foundations, and our Donor Advised Funds. For more information about this program, contact David Farkas: david@phlf.org or 412-471-5808 ext. 516.

$10,000– Beth Shalom Congregation, Squirrel Hill—Cornice repair

$10,000– Church of The Ascension, Shadyside— Stained glass window repairs

$10,000– First Baptist Church of Pittsburgh, Oakland– Repointing & slate roof repairs

$10,000– First Evangelical Lutheran Church, Downtown–– Exterior wood door repairs & repointing

$10,000– First Presbyterian Church, Downtown–– Exterior wood door repairs

$10,000– Good Samaritan Baptist Church, Hill District–– Roof replacement

$10,000– Homestead United Presbyterian, Homestead– Masonry repairs

$5,000– Natrona Heights Presbyterian Church, Natrona Heights, PA– Slate roof repairs

$10,000– Shepherd’s Heart Fellowship, Uptown– Repoint exterior

$10,000– Sixth Presbyterian Church, Squirrel Hill– Stained glass window repairs

$10,000– St. Nicholas Croatian Church, Millvale, PA– Roof replacement

$10,000– St. Phillip Parish, Crafton, PA– Restore exterior wood doors

$10,000– Tarentum Central Presbyterian, Tarentum, PA– Stained glass window repairs

$7,500– The Union Project, East Liberty– Replace lobby roof

$10,000– Third Presbyterian Church, Shadyside– Restore exterior wood doors

$2,825– Tree of Life Open Bible Church, Brookline, PA– Repoint entry stairs

$9,279– Valley View Presbyterian Church, Garfield– Stained glass window repairs

-

Grant to Fund Educational Program on African American History

The Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation is pleased to announce a grant of $41,378 from the African American Civil Rights Grant Program, through the Historic Preservation Fund administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior.

The grant will enable PHLF to design an educational program around the National Negro Opera House, that will not only highlight the history and significance of the building in African American history, but also the importance of its restoration and preservation. The program will be titled, A Legacy in Stone: Homewood’s National Negro Opera House and the Confluence of Pittsburgh’s African American Culture.

“We are delighted to receive this grant, which will enable us to not only deepen our understanding of the significance of the National Negro Opera House and its place in American history but also tells the greater story of the African American experience in Pittsburgh in the first half of the Twentieth Century,” said PHLF President Michael Sriprasert.

As part of this program, PHLF will prepare and submit a nomination of the National Negro Opera House for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. This will include the creation of an educational component to explore the history of the building, bringing an understanding of the depth of Pittsburgh’s African American cultural legacy to a younger generation of students.

This grant is one of 53 projects in 20 states funded by a total of $15,035,000 from the National Park Service’s African American Civil Rights Grant Program.

“This grant makes it possible for us to work with educators in sharing the history of the National Negro Opera House with more students, helping even more people learn about and appreciate the significant African American history reflected in this landmark building in Homewood,” said PHLF Co-Director of Education, Sarah Greenwald.

Listed in 2020 as one of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places, by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, the Queen Anne-style house in the Homewood neighborhood of Pittsburgh, was once a place of prominence for African American entertainers, musicians, and sports figures.

The house served as a lodging house and a community space for prominent African Americans visiting Pittsburgh during the era of segregation when it was not easy for African Americans to gain lodging in white-owned establishments. It is currently undergoing efforts to renovate and restore it by a group of stakeholders led by its owner Jonnet Solomon.

PHLF has been working with Ms. Solomon to help implement a strategy of restoration and renovation of the building. This includes an initial stabilization study to assess the feasibility of restoration and an ongoing engineering assessment of the building to analyze stabilization of the hillside behind the house and restoration of a historic wall along the property.

-

“Building Buddies” — A Giant Puzzle, Art Activity, and Outdoor Exploration — Teaches the Value of Our Buildings

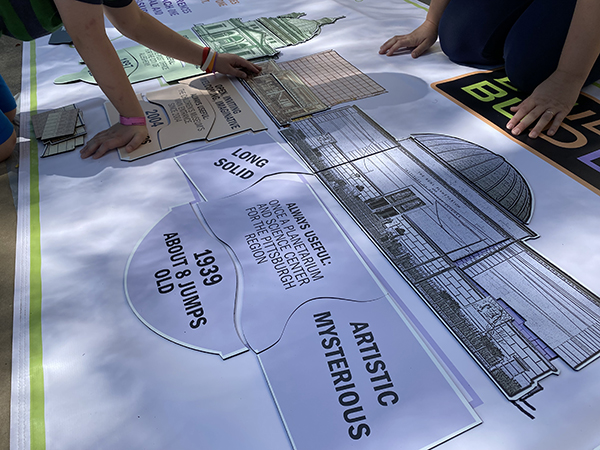

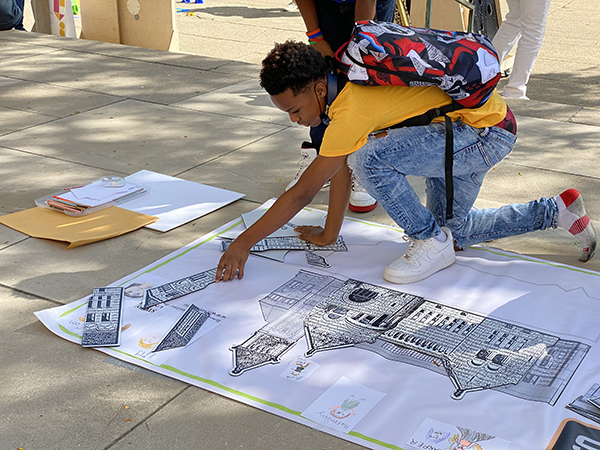

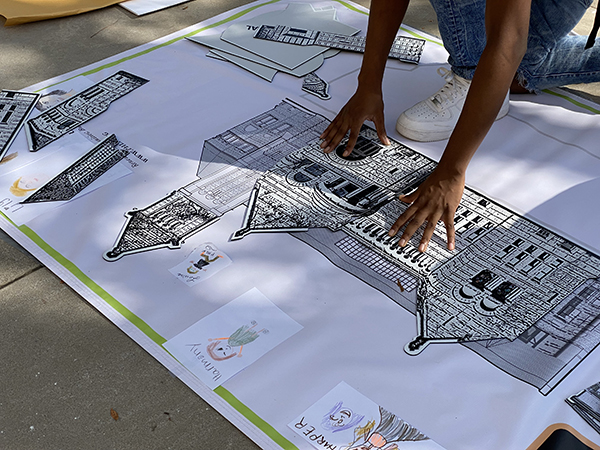

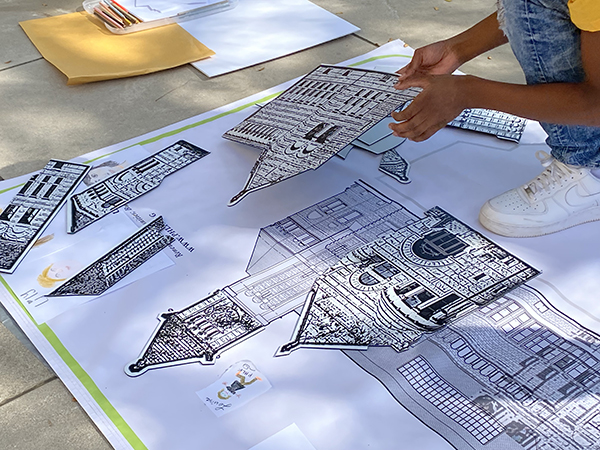

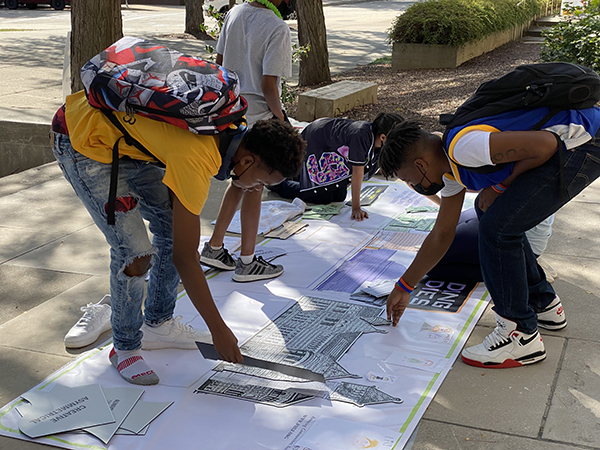

Young learners and their families put together the PHLF-created “Building Buddies” puzzle at the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh’s Corridor Free Day on September 30, 2021.

As part of the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh’s Corridor Free Day on September 30, 2021, we presented a creative “Building Buddies” program in which learners of all ages helped put together a giant puzzle of the Children’s Museum campus. Through the exercise, participants learned about the details that define the character of each of the four museum buildings. They also drew pictures of themselves and added them to the giant “Building Buddies” puzzle.

PHLF Co-Director of Education Sarah Greenwald and Education Adviser Louise Sturgess, guided learners through various activities, helping everyone see the beauty and discover the story of the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh.

“Building Buddies” was created by the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation and Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh, thanks to funding from the McSwigan Family Foundation Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, Gailliot Family Foundation, and Grambrindi Davies Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation.

An online version of “Building Buddies” is available for anyone interested in exploring the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh’s family of buildings. Through an interactive game, matching activity, puzzles, and drawing activity, children learn that the four museum buildings have different styles, colors, shapes, details, and ages. It is the differences that make each building––and each one of us––unique and worth treasuring.

Use the learning platform Nearpod (free for students) on your phone or computer to explore “Building Buddies.” Click HERE to access these creative, educational activities.

We thank Megan Pen, PHLF’s 2020 summer intern from CMU’s Heinz College and College of Fine Arts, for adapting PHLF’s “Building Buddies” program to a series of interactive, online activities.

-

Carnegie Mellon University Students Explore Pittsburgh

As part of Carnegie Mellon University’s Pittsburgh Connections program, freshman students had the opportunity to explore Pittsburgh’s distinctive architectural character and historic significance from PHLF Co-Directors of education Tracy Myers and Sarah Greenwald. Tour stops included buildings along Grant Street, Pittsburgh’s grand civic boulevard.

This time of the year marks a common annual passage: that of college freshmen settling into campus and university life. To introduce first-year students from Carnegie Mellon University to Pittsburgh’s historic built environment and preservation’s role in sustaining it, PHLF Co-Directors of Education Tracy Myers and Sarah Greenwald led students on a special tour, titled “Hello My Name is Pittsburgh,” through Downtown and the Lower Hill District.

Twenty-nine students, almost none of whom were familiar with Pittsburgh before the tour, trekked through an introductory survey of the City’s architecturally significant buildings, districts, and green spaces. Through the tour, students were encouraged to think of themselves as taking a journey across time––from Pittsburgh’s establishment as an outpost of Empire during the French & Indian War, to its industrial history, postwar development, and more recent renewal as the “Renaissance City.”

In a vigorous walk that took in such landmarks and historically significant sites like the Fort Pitt Blockhouse, Gateway Center, the Allegheny County Courthouse, and the former Civic Arena site, students learned that, like all cities, Pittsburgh is a living, ever-evolving combination of old and new buildings.

The tour ended at Freedom Corner, where the students were encouraged to contemplate how historic preservation can help renew communities and build pride in contrast to massive demolition of the built environment.

“We are so pleased that CMU asked us to be part of its freshman orientation program. The old saying that you only get one chance to make a first impression is as true of places as it is of people. Sarah and I were excited to both show these young people our city and tell them of historic preservation’s very important role in keeping Pittsburgh distinctive,” said Tracy.

“It is our hope that whether or not they stay in the city after their university experience, these students see the relevance of history and understand that architectural preservation is completely aligned with their generation’s concern for the environment and the planet,” she added.

If you are interested in a similar experience for your education group, contact our education department by calling 412-471-5808 or emailing Tracy Myers at tracy@phlf.org.