Category Archive: Uncategorized

-

Pine-Richland Sixth-Graders Complete Architecture Apprenticeship

A group of sixth-graders posing as the members of an architecture firm, MCCV Architects, made a presentation showing the evolution of their project for the Pine-Richland Architecture Apprenticeship. This team and ten others designed re-uses of a small building on the Eden Hall campus of Chatham University to sustainably address needs specified by the university, which served as the students’ client. For the ninth consecutive year, gifted students at Eden Hall Upper Elementary School in the Pine-Richland School District took part in a program that brings to light the mutually reinforcing benefits of historic preservation and environmental sustainability.

Working in eleven teams, the 45 sixth-graders proposed ideas for re-use of a small 1913 Dutch-gabled house on the Eden Hall campus of Chatham University as either a recreation center, a building to support campus farm operations, or a bicycle repair and rental shop.

The three programs were specified by faculty and staff at Chatham, the “client,” which has partnered with our organization since the program’s inception. The students’ work started in the fall semester, culminating in formal presentations, in early February, to their teachers, a team of architect mentors brought together by our organization, and a large number of parents.

Awards were given to recognize not only outstanding design, but also achievement in presentation—i.e., in how well the students communicated their ideas through architectural drawings and models.

Mary Whitney, who is the sustainability director for Chatham’s campuses, said she was “blown away” by the students’ designs. “They really did their research and listened to what we [the client] told them.”

The Architecture Apprenticeship program fulfills some of Pennsylvania’s educational standards for career education by introducing students to the various professional roles involved in architecture, historic preservation, and sustainability.

Jennifer Kopach and Joanna Sovek, the teachers, also see the program’s iterative process as imparting to the students an invaluable framework for navigating life, regardless of the fields the students eventually pursue.

“The students have to respond to the client’s needs and incorporate into their designs the feedback they receive from the architect mentors in multiple reviews,” said the teachers.

Through that process, they added, “the students learn that nothing is perfect on the first try and that being able to accept and integrate constructive criticism is important, and by working in teams, they also come to understand the need for compromise.”

-

Architectural Design Challenge Helps Sixth Graders Imagine Reuse of Historic House

Gifted sixth-grade students from Eden Hall Upper Elementary in the Pine-Richland School District gather on the steps of the Esther Barazzone Center at Chatham University’s Eden Hall Campus after making final presentations in PHLF’s 8th Annual Architectural Challenge. Accompanying them are their teachers, the panel of architects who reviewed their work, and representatives of the Eden Hall Campus who were the students’ clients. Thirty-one gifted sixth-grade students from Pine-Richland School District’s Eden Hall Upper Elementary School presented design concepts for repurposing a 111-year-old house on the Eden Hall campus of Chatham University, on January 27.

The presentations were part of our Architectural Design Challenge, a component of our educational program to help young people imagine how to relate to our city and region’s architecture, and historic preservation of the built environment. As it has been in previous years, the Challenge site was the Morledge House—a roughly 1800-square-foot house and garage with a Dutch gambrel roof, located on the Eden Hall Campus.

This year, Pine-Richland teachers Joanna Sovek and Jennifer Kopach proposed a substantial change in the program. Instead of designing for whatever use suited their fancy, student teams would now work for a client that had specific programmatic requirements.

“The State of Pennsylvania’s academic standards include a career awareness component for our kids. We thought this program could provide a great opportunity to give students direct experience working in a creative, collaborative way that requires them to solve particular architectural problems,” said Ms. Sovek and Ms. Kopach.

The teachers’ idea meshed perfectly with the conditions on the Eden Hall Campus, which has been a valued partner since we created the program in 2015.

Kelly Henderson, K-12 education coordinator at Eden Hall, canvased colleagues there about the unfilled facilities needs in their departments. Together, they came up with three possible architectural programs for the eight student teams to wrangle out of the Morledge House:

- A recreational center where students could relax—whether passively, by simply “chilling,” or actively, through outdoor or indoor diversions.

- A bike shop, at which the campus’s bikes would be stored, rented, and repaired and where students could learn to fix bicycles.

- A space to support the farm team, which grows food that is used on campus and conducts research on agricultural sustainability.

Student teams met with the clients during the program to learn about what they needed or wanted, and to ensure that they were being responsive to the clients.

To make the Challenge even more realistic, students assumed specific roles that would be found on an architectural project with this scope and goals: LEED-certified architect, preservationist, landscape designer, interior designer, drafter/digital modeler, and project manager.

Students presented their projects to a panel of four architects (Ray Bowman, Nicole Cicconi, Paul Tellers, and Rob Zoelle) and two of the clients. Awards were presented in several categories that recognized the varied skills needed for complex architectural projects. The panel gave the award for Best Project Overall to the team calling itself Apex Architecture Firm, for “The Bike Barn.”

Inspired by the “casual-meets-elegant” aesthetic of so-called Wedding Barns, it maintained the building form and reinforced the structure to accommodate heavier loads; used reclaimed wood for storage furniture and other furnishings; and proposed use of a pulley system to move heavy boxes to the attic-level storage. Dr. Mary Whitney, Sustainability Director for Chatham University and the client for the bike shop program, was impressed by the team’s responsiveness to her feedback on its initial design. “I felt very heard: they really listened to what I told them!”

Ms. Kopach and Ms. Sovek were “beyond proud” of their students for the sophistication of their design solutions and the maturity with which the teams made their well-practiced presentations. By way of closing remarks, juror Paul Tellers, a PHLF docent and practicing architect, told the students that the problem-solving process they experienced through this program would serve them well in the future.

“Working together, learning to compromise, responding to specific needs, communicating your ideas—you need to be good at all these things, regardless of what you do later in life,” he said.

In addition, learning about historic preservation and sustainability are the big lessons to be gleaned from this Architectural Design Challenge.

-

Architecture Feature: The African Heritage Room at the University of Pittsburgh

The design of the African Heritage Room was formally presented and approved on May 8, 1986. From left to right: Maxine Bruhns (former Director of the Nationality Rooms Program), William J. Bates (Architect), Dr. Larry Glasco (Concept Chairman), and Wesley W. Posvar (former President of the University of Pittsburgh).

By Larry Glasco

Both individually and collectively, the Nationality Rooms at the University of Pittsburgh constitute some of the most dramatic and beautiful examples of interior architecture in the city. Indeed, one might say in the world, for there is nothing like them anyplace else.

The Nationality Rooms program began in the late 1920s as part of an effort to enlist Pittsburgh’s nationality groups in support of the newly constructed Cathedral of Learning. The University stipulated that the rooms must be authentic representations of a national culture, must be cultural rather than political in design, and must represent a time before 1787, the year of the University’s founding.

Today, some 31 rooms grace the first and third floors of the Cathedral of Learning. They attract some 100,000 visitors annually, and serve as classrooms, regularly exposing students to a variety of world cultures.

In addition to their beauty, what most attracted me to the rooms is that they are designed by the nationality groups, not by the University. This makes them an expression of how the groups think of themselves and want to be perceived by others. The trade-off is that each group has to pay for its room, with the University agreeing to provide subsequent upkeep.

In addition to their beauty, what most attracted me to the rooms is that they are designed by the nationality groups, not by the University. This makes them an expression of how the groups think of themselves and want to be perceived by others. The trade-off is that each group has to pay for its room, with the University agreeing to provide subsequent upkeep.As professor of African-American history at the University of Pittsburgh, I was excited to serve as chair of the Design Committee for the African Heritage Room. The most immediate problem we faced was that Africa is a continent, not a nationality. How to create a room that reflects that fact? The answer: designate the room as the African Heritage Room, meant to reflect the identity and cultural heritage—or at least the African cultural heritage—of black Americans.

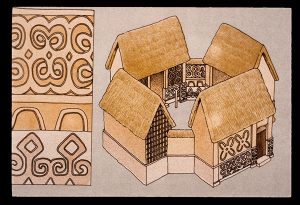

That identity is Pan-African, not based on any one African tribe or nationality, which allowed us to create a room that is both a blend of many cultural elements and an example of a specific African culture. We chose a courtyard as the room’s unifying concept, a place of gathering for friends and family. The courtyard is a feature of home life throughout the continent–the counterpart of the American front porch, backyard, and family room all rolled into one.

The African Heritage room is also a specific example of African architecture – that of the Asante, or Ashanti, people of Ghana. Finally, the room features (in subtle bas relief) examples of African written languages, musical instruments, art, science and mathematics.

One of my greatest pleasures was documenting the authenticity of everything in the room. To examine African artifacts, I visited the British Museum in London, the Museum of Mankind in Paris, and the Museum of Ethnology in Munich. I also traveled to Ghana, where I observed and photographed traditional temples and shrines in the countryside.

The room benefited from contributions by many individuals. African students at Pitt advised us about the importance of the courtyard. Lamidi Fakeye, a renowned traditional woodcarver from Nigeria, created the door, chalkboard, and lectern. Kweku Andrews, a Ghanaian professor of art, made the roof, stools and plasterwork.

The room benefited from contributions by many individuals. African students at Pitt advised us about the importance of the courtyard. Lamidi Fakeye, a renowned traditional woodcarver from Nigeria, created the door, chalkboard, and lectern. Kweku Andrews, a Ghanaian professor of art, made the roof, stools and plasterwork.Pittsburgh-based architect William Bates (also a member of PHLF) turned ideas, photographs and documentation into a beautiful reality. Maxine Bruhns, the long-time director of the Nationality Rooms program, supported us every step of the way. Committee members, drawn from Pittsburgh’s black community, kept the faith and, under the leadership of Nancy Lee, raised over $150,000.

Today, the room’s current chair, Donna Alexander, leads the African Heritage Classroom Committee in advancing appreciation for Africa and African culture. Since the opening in 1989, it has been a joy to hear tour guides relate how the African Room remains one of the most popular and admired of all the many beautiful rooms.

The African Room’s current focus is providing scholarships for students to study and/or work in Africa. In addition, at Christmas time, the African room – like all the other rooms –is decorated, in our case with a Kwanzaa motif. In these, and in many other ways, the Nationality Rooms Program brings people together in a collective, mutually supportive way to celebrate their nationality alongside that of others. It promotes the sort of interracial and inter-ethnic atmosphere that is worthy of being cherished and cultivated.

Editor’s Note: We were saddened to learn of the recent death of Maxine Bruhns, the former longtime director of the Nationality Rooms Program at the University of Pittsburgh. She was a great friend of our organization, and we worked together for many years on a number of advocacy issues, including our support for the Nationality Rooms, which our organization awarded a historic landmark plaque. Read her obituary featured in the Post-Gazette here.

Larry Glasco is Associate Professor of History at the University of Pittsburgh. Since coming to the University of Pittsburgh’s History Department in 1969, he has focused on African-American history, both locally and globally. He is a longtime member and Board Member of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. He is a co-author of August Wilson: Pittsburgh Places in His Life and Plays, which was published by PHLF.