Category Archive: Essays

-

Architecture Feature: B. F. Jones Memorial Library, Aliquippa, Pa.

“Classic Lines, Sufficiently Modern, a Charming Freshness, and Dignity of Style”: B. F. Jones Memorial Library, Aliquippa, Pa.

By Albert Tannler

Adhering strikingly to the classic lines of the Renaissance, The B. F. Jones Memorial Library is nevertheless sufficiently modern in its treatment to suggest a charming freshness which in no way detracts from its dignity of style.— Programme of the Presentation and Dedication of B. F. Jones Memorial Library. Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, February 1, 1929

Angelique Bamberg notes:

The present City of Aliquippa was created from the merger of the towns of Woodlawn and Aliquippa in 1928. . . . The city’s history is closely tied to that of the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad (P&LERR) and the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company. The P&LERR’s line from Pittsburgh to Youngstown, OH was completed in 1879. To encourage passenger traffic from both cities, the railroad opened an amusement park, Aliquippa Park, roughly equidistant between them in 1880. The name Aliquippa was chosen by the President of the P&LERR, who had an interest in Native American history; Queen Aliquippa was a leader of the Seneca Tribe in the 18th century. There is no evidence of a direct association between the historical figure of Aliquippa and the town site, however.[1]

The Building and the Donor

According to the National Register Nomination Form, “the library serves as a fitting memorial for one of the industrial giants and cofounders of Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, Benjamin Franklin Jones, Sr. [1824-1903] His contributions, along with those of his family and associates, are part of the history of steel making and the socio-economic impact which resulted from J&L’s growth. His daughter, Mrs. Elisabeth McMasters (Jones) Horne, recognizing the importance of individual development, offered to erect a library more responsive to the needs of the public. Her generous gift to the community has probably had as much effect on the growth and development of the community as did the steel plant several blocks away.”[2]

According to the National Register Nomination Form, “the library serves as a fitting memorial for one of the industrial giants and cofounders of Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, Benjamin Franklin Jones, Sr. [1824-1903] His contributions, along with those of his family and associates, are part of the history of steel making and the socio-economic impact which resulted from J&L’s growth. His daughter, Mrs. Elisabeth McMasters (Jones) Horne, recognizing the importance of individual development, offered to erect a library more responsive to the needs of the public. Her generous gift to the community has probably had as much effect on the growth and development of the community as did the steel plant several blocks away.”[2]The National Register of Historic Places Inventory––Nomination Form of 1974 gives a detailed listing of the elements of the building while noting: “The interior has been little altered although some rooms are no longer used for the purposes for which they were designed.”[3]

The February 1, 1929 Programme of the Presentation and Dedication of B. F. Jones Memorial Library, gives a sense of character of the building:

The library building . . . is remarkable not alone for its architectural beauty. The entire structure reflects the thoroughness with which the project was studied long before erection, in order that the completed building might lend itself in every way to the work and service to be accomplished. Consequently, one finds book stacks, work rooms, rest rooms, a librarians office, an exhibition room, furniture, filing cases and other carefully selected equipment, all so favorable [sic] situated and co-ordinated that the building is practically perfect as to workability. Building materials include “grey Indiana limestone . . . Kasota marble . . . and Travertine from Italy.”

The Architect and the Artists

Brandon Smith was among a handful of the most talented eclectic architects to have practiced in western Pennsylvania. One of the last in a noted generation of traditionalists, his work at Fox Chapel Golf Club, The Edgeworth Club, and on a series of fine residential designs are distinguished by thoughtful accommodation and unfailingly gracious resolution. He is deservedly remembered as Pittsburgh’s most sought after high society architect.

Smith was born in Allegheny City in 1889. His parents were Charles O. and Elizabeth Benn Smith. His family was of German and English descent and his father owned the Sterling White Lead Co., which was later sold to the National Lead Co.

Brandon graduated from the old Central High School, his first job was demonstrating roadsters and early automobiles. He attended architectural classes at Carnegie Tech in the years 1910 – 1912. He was a student of unmistakable talent and sophistication, but he never graduated from the program. He enlisted in the Army in 1917 and served as Lieutenant in the Field Artillery during World War I.

While stationed in Salt Lake, Utah, he met and later married Kate Nelson. They had two daughters, Marian and Barbara.

It’s important to note that early in his career Brandon worked in the office of Alden & Harlow. From 1920 – 1927 Brandon worked in partnership with Paul A. Bartholomew, a University of Pennsylvania graduate who had also worked at Alden & Harlow. Bartholomew & Smith had offices in Pittsburgh and Greensburg.[4]

The years of the Great Depression and the Second World War were very hard on architectural careers and Brandon despaired that the profession would never recover. During the war years some of his beautiful drawings for designs that would never be built were exhibited by the Pittsburgh Architectural Club, and by the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh. He remained a traditionalist, opposed modernist ideas, and retired to Florida in 1955. There he also designed a few buildings, and died in Pensacola in 1962 at the age of 72. He is buried in Arlington Cemetery.[5]

David Vater observes that “the B.F. Jones Memorial Library at 603 Franklin Street in Aliquippa, PA . . . is without question the finest building in this once prosperous steel town. . . . It’s well worth a visit.” The National Register of Historic Places form notes that “Three large 30 light windows are set behind the recessed columns. . . The side elevations each have three windows of 30 lights.” David Vater quotes Smith’s daughter who observed that her father “always insisted upon driving convertibles because he was a claustrophobic, like the bright yellow Nash and a little green MG he used to race about in. Perhaps his claustrophobia was the motive for the generous fenestration and a preoccupation with openness in many of his architectural designs.”[6]

Artwork in the library consists of a larger-than-life bronze and marble statue of B. F. Jones by Robert Aiken of New York City; the color scheme in the building was planned by Norah Thorpe of New York City; Mrs. Horne’s portrait is by Dutch portrait painter Alfred Hoen; and the leaded glass windows are by Henry Hunt of Hunt Studios, Pittsburgh.

Bibliography

Programme of the Presentation and Dedication of B. F. Jones Memorial Library. Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, February 1, 1929.

50th Anniversary, B.F. Jones Memorial Library 1929-1979. Aliquippa, Pennsylvania.

- F. Jones Memorial Library, National Register of Historic Places Inventory––Nomination Form. Placed on the NRHP on December 15, 1974.

Vater, David J. “Brandon Smith, Eclectic Architect.” Fox Chapel Golf Club, October 2, 2005.

Bamberg, Angelique. “An Architectural Inventory, Franklin Avenue Aliquippa, PA. Report of Findings and Recommendations.” Prepared for the Community Development Program of Beaver County in cooperation with Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office by Clio Consulting, June 12, 2016.

[1] Angelique Bamberg, An Architectural Inventory, Franklin Avenue Aliquippa, Pa, 3.

[2] “B. F. Jones Memorial Library,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, n.p.

[3] Ibid.

[4] David Vater notes that Smith later partnered with Harold O. Rief, with offices in downtown Pittsburgh.

[5] Vater, “Brandon Smith, Eclectic Architect,” 2005.

[6] Ibid.

-

An Essay On Town Planning in Upstate New York

On a recent trip to Upstate New York, Arthur Ziegler, president of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation (PHLF), toured the historic Chautauqua community, Buffalo’s Canalside, a waterfront development on the Erie Canal Harbor in Buffalo, and Niagara Falls. He recounts the trips and some of his thoughts and observations on the history of the area, sense of place, and town planning in the essay below.

By Arthur Ziegler

It had been many years since I last visited the Chautauqua Institution near Jamestown, New York, when I drove up there a couple of weeks ago to take in a performance by Garrison Keillor, the noted author, humorist, and radio personality. The Chautauqua Institution, of course, was embroiled in considerable controversy in recent years concerning its demolition of its historic amphitheater, which had been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. We, at PHLF, joined the preservationist voices from all across the country in opposition to the Institution’s plans, but the board of directors of the Institution won out and raised over $23 million to demolish it and build what is actually a rather good replica.

From what I observed, they have created a better access for physically handicapped patrons, a large addition to the theater for back-of-the-house improvements and space needed for performers. The wooden benches and the spaces, the stage, are all replicated and the organ is in place. One would hardly know the difference but one can feel the loss of the patina of time that one felt in the former amphitheater.

For this opening week Garrison Keillor performed with two cast mates from his old radio variety show, A Prairie Home Companion, and the acoustics in the amphitheater were perfect both for performers and the several thousand attendees who joined in singing old-time songs. A new plaza will be developed in front of the theater in the coming year to make that area more inviting.

It is the planning—or lack of planning—that makes Chautauqua itself so welcoming and really endearing. There is a relative grid pattern of streets except for a curving street from the lakefront up toward the hotel. There are few curbs, few sidewalks, and yards go right to the edge of the asphalt and almost every yard has a front yard garden or little lawn. In late July, the flowers were all in bloom, making the town feel very inviting. The informality of the roads and gardens is rare in America and largely disallowed anywhere in planning today.

The architecture of Chautauqua, largely Gothic, board and batten, and some classical, is an endless treat to the eye and every time one walks for about a block, no matter how often it is repeated, one sees new details. In Chautauqua, it appears, that no house has setback requirements and there is no single-use of land i.e., a street block might have single-family houses, inns, rental cottages, lecture hall, restaurant, art center. Everything exists in harmony, a notion that runs counter to our contemporary ideas of urban planning where different uses are isolated from one another.

What they have in Chautauqua that also helps to make the community feel inviting and in-tune with nature is that shade prevails. The town is filled with great trees everywhere, a mixture of deciduous and conifers. One can walk the entire town with comfort because of its short street blocks. There, I recalled that Jane Jacobs taught us the value of short blocks.

Amidst the charm of the town, I was reminded that the community in Chautauqua was founded as a religious retreat by the Methodist churches and religion still prevails. The residents and visitors are— at least when I was there— almost entirely white, and aging. Occupants of houses now seem to be permitted to have alcoholic beverages on their porches but the great hotel has limited its offerings to wine and beer. While the artistic and intellectual programs are plentiful and varied, Chautauqua still seemed to be limited in its demographic appeal and I wondered how many of the people that were there will be there 10 years from now due to age and infirmity. In the future, I wondered: What will bring younger more diversified people there?

Buffalo

From Chautauqua, I drove farther north along I-90 to Buffalo, New York, to visit and see Canalside, a waterfront redevelopment in an historic district on the city’s inner harbor. Located within Buffalo’s Downtown, the redevelopment of the area started in 2005 when the state of New York formed the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation, a state agency that was charged with planning the redevelopment of this historic site to help boost Buffalo’s economic resurgence.

Stanton Eckstut, a leading preservation planner and architect with Perkins Eastman— and who has done considerable work with our organization over the years— was the project designer and through his vision the Erie Canal has been resurrected, water is flowing, and a Downtown playground has been established all around it with a number of developments scheduled to come.

Stanton Eckstut, a leading preservation planner and architect with Perkins Eastman— and who has done considerable work with our organization over the years— was the project designer and through his vision the Erie Canal has been resurrected, water is flowing, and a Downtown playground has been established all around it with a number of developments scheduled to come.A light rail line comes right to the project connecting to the business area a couple of blocks away. Here is a planning triumph, I thought, in that it is bringing residents and visitors back Downtown and in the winter when the water is frozen in the canal, it is a hugely popular ice skating rink. I saw a group of youngsters enjoying hula hoops, some oldsters talking to one another in a collection of Adirondack chairs, and people enjoying views of the water, the marina, and a great naval destroyer anchored there. A highway soars over the site on concrete posts and it has been retained and people frolic underneath it.

The area has been pedestrianized with easy access by vehicle and parking and various areas are treated in different ways, some with wooden boardwalks, some with lawns, some with blocks that might have been used in the ships that sailed there, old foundations from the canal and adjoining buildings have been excavated, and interpretive panels have been displayed with good graphics narrating the history of the area.

The area has been pedestrianized with easy access by vehicle and parking and various areas are treated in different ways, some with wooden boardwalks, some with lawns, some with blocks that might have been used in the ships that sailed there, old foundations from the canal and adjoining buildings have been excavated, and interpretive panels have been displayed with good graphics narrating the history of the area.I could see that Stan Eckstut and his team sought to renew the core of the city as a major attraction by reviving its history. In doing planning anywhere, Stan first looks to the history of what happened at a particular site and then develops relevant concepts for people living, working, and playing in the space today. In Buffalo, unlike Chautauqua, people of every age and race were there in abundance and the place felt alive.

It also occurred to me that Canalside is very different from our own historic Point State Park in Pittsburgh, which is really disconnected from the rest of Downtown. Here, our history in Point State Park is treated modestly and was recently mostly covered up. It is no wonder that the park is not heavily used unless there is a special event.

At Point State Park, the museum is almost hidden away and the Block House was saved only through the intrepid determination of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The foundations of the historic buildings, historic wharfs, were all eliminated in favor of plain concrete walkways around the rivers’ edges. It is beautiful and pristine but not in any way equivalent to the educational playground I saw at Canalside.

Niagara Falls

About half an hour’s drive north of Buffalo lies the majestic Niagara Falls. On the American side of the falls, we have a Downtown whose street pattern is elusive. Traffic overwhelms the town, parking is not neatly provided. The park and the falls are hidden beyond various tourist stores in the town. Way finding is hard for pedestrian or drivers but when one finally arrives at the park, which is maintained by the National Park Service, the landscaping, unlike at Chautauqua or Canalside, leaves a lot to be desired. It feels more like the remnants of a landscaped park, with shrubs and trees looking like they need nourishment. The lawn in many places is just dirt. Granted that there are many thousands of visitors here and it can be hard to maintain landscaping but it is done across the river in Canada very well.

Signage is poor if it exists at all and one can end up driving around and around the same block or doing the same on foot because each block seems to be lined with the same tourist shops. Niagara Falls is a major world attraction and we should have there a town outstanding for its architecture and its linkages to the river and the Falls and demonstrate our country’s planning and landscaping to the best.

One very good thing that can be said about Niagara Falls is that the population is highly diversified. People from every country, every ethnic background, and every age are there and the great natural wonder of the Falls delivers a spectacle that somehow equalizes the human beings who come to enjoy it and they seem to enjoy one another.

As I reflect on my journey to this part of Upstate New York, I can’t help but wonder:

- How will Chautauqua Institute move toward the future?

- How should Buffalo work to spin off more good economic development for the future by its investment in the visionary Canalside?

- How can Niagara Falls reconfigure itself to be in itself an attraction that befits and enhances the natural attraction that brings people there?

-

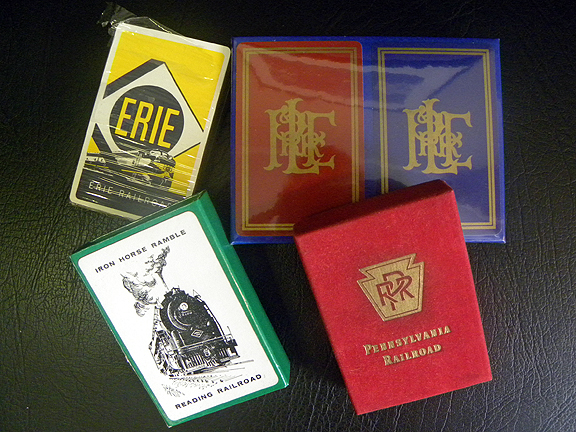

Fairbanks Feature: Playing Cards from Well Known Rail Lines

James D. Van Trump Library | Frank B. Fairbanks Transportation Archive | Fairbanks Features

Showcasing a variety of materials located in the Frank B. Fairbanks Rail Transportation Archive

Showcasing a variety of materials located in the Frank B. Fairbanks Rail Transportation ArchiveNo. 7 Presentation

Fairbanks Feature: Playing Cards from Well Known Rail Lines

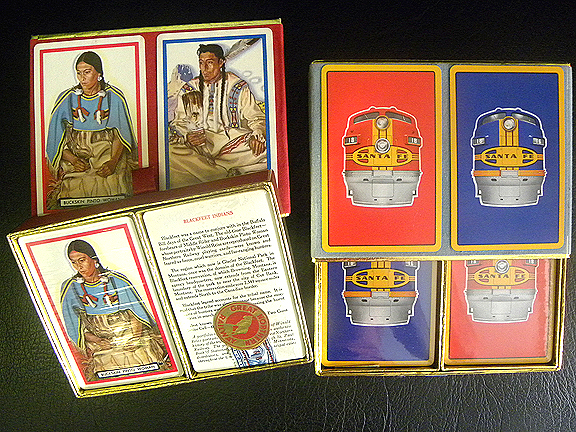

In the golden days of railroad travel, amenities abounded for the rider, especially on the long distance excursions. Railroads provided decks of cards to passengers, many times given out free. These cards were good advertisements for the sights that could be seen along the way. They also showed pictures of the rail cars and engines of that particular rail line and/or reminders of the great historical background of a railroad. Many of these cards came in durable boxes; some are covered in velvet-like material. These cards were not produced to be discarded at the end of the journey. There is a high quality, good, long-lasting feel to the cards.

Frank Fairbanks collected these cards as he traveled the United States. The Fairbanks Archive has playing cards from 46 different rail lines, given out on train trips between 1952 through 1965. Some of the decks still have their seals intact, and some have been opened but the cards have never been used. All the boxes of playing cards are on display in the Archive, and patrons can handle and examine each box.

- “Pennsylvania Collection” Four rail lines represented: Reading, Lake Erie, Pennsylvania, and Erie Railroad

- Great Northern Railway and The Santa Fe

- Wabash and the Chicago and North Western Railway Company

- Louisville & Nashville R.R., Burlington Vista-Dome Zephyr, and The Atlantic Coast Line

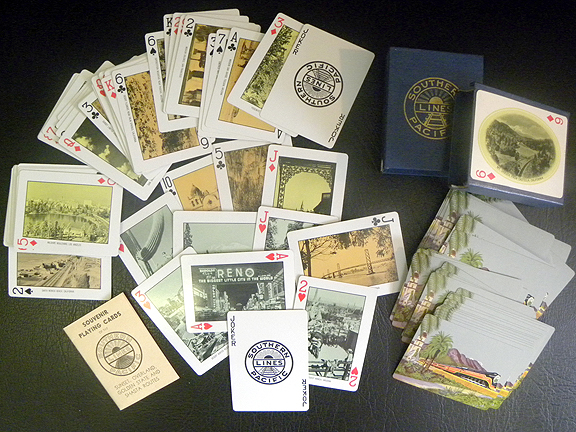

- Two very interesting decks come from the Southern Pacific Lines. Each deck is different. One side of the card has a lovely color photo of the train itself. The other side has a photo of a sight along the route. With 52 cards plus extra cards in each deck, there are over 100 different well known photos along these routes in the time period of the 1950s to 1960s.

The Frank B. Fairbanks Rail Transportation Archive is open by appointment on Mondays, from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Use of the archive is free to PHLF members (one of the benefits!); non-members are assessed a $10 use fee.

The Archive is located on the fourth floor of The Landmarks Building at Station Square, in the offices of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

To schedule an appointment, email Librarian James Halttunen: James@phlf.org

-

Students Pen a Historical Look at Homestead – Book Features Poems, Photos, Essays

Thursday, June 10, 2010By Dana Vogel, Pittsburgh Post-GazetteThanks to the Young Preservationists Association — a nonprofit organization that encourages the participation of young people in historic preservation — the history of Homestead has come alive for a group of Propel Andrew Street High School students.

The association’s Youth Main Street Advisers Program and seven students from Propel Andrew Street held a book signing last Thursday in Homestead to launch their new book, “Take a Walk From the Past to the Future of Eighth Avenue,” published by Red Engine Press.

The book was the result of a year-long project to better understand Homestead’s historic commercial district and to envision a new future.

“Take a Walk From the Past to the Future of Eighth Avenue,” which is divided into three parts representing the past, present and future of Eighth Avenue, features essays, poems and interviews by the students. The book also includes photographs of the neighborhood from the past and present.

Dan Holland, CEO of the youth group, explained the idea for a book came from a desire to do something more enduring than a video. “We wanted something you can see, feel, touch,” he said.

The rest of the story came down to a combination of luck and preparedness, Mr. Holland said. He explained that he ran into his longtime friend Jeremy Resnick, executive director and founder of Propel, at a barber shop and mentioned his idea. With a grant from the Grable Foundation and approval from Propel superintendent Carol Wooten, students from Propel Andrew Street in Munhall turned Mr. Holland’s dream into a reality.

The most significant result of the project seems to be its effect on the students.

Stephanie Nachemja-Bunton, a teacher at Propel Andrew Street and the group’s adviser, said, despite a few initial setbacks, “the seven students who completed the books were dedicated and did a wonderful job.”

She said that in addition to researching Homestead in books and on the Internet, the students took a number of tours of the borough.

Dr. Wooten said not only did the project give the students a stronger sense of community, but it also helped them to meet Pennsylvania academic standards, particularly in communications. She also emphasized that the group aspect of the project will help to prepare the students for the workplace.

The students also agreed that, in the end, the project was about learning.

“The experience was good. I gained knowledge and learned about the community,” said MalikQua Salter, a 17-year-old junior from Rankin, who contributed an essay, interview and photo essay to the book.

MalikQua, whose father grew up in Homestead, wrote in the book, “Eighth Avenue is no longer what it used to be, but many people are coming together to make it what it once was.”

Freshman Janiece Hall, 15, of Penn Hills, said, “I learned about interviewing and communication skills.”

Janiece, who has a poem, photo essay, interview and essay feature in the book, also said that while the project seemed difficult at first, “as it was coming together, it got easier.”

In her poem, she describes earlier excitement on the avenue which is “now as empty as a dried up river bed.”

The result of all the hard work seems well worth it to MalikQua. “The book turned out great. We worked hard and put in a lot of effort, and it’s pretty good,” she said.

Echoing her sentiments, Mr. Holland said: “I’m thrilled with the book. It’s a very compelling product.

“Our hope is that the community will embrace this book as well,” he added.

For a copy of “Take a Walk From the Past to the Future of Eighth Avenue,” call the Young Preservationists Association at 412-363-5964.

-

Howard Gilman Wilbert (1891-1966), Pittsburgh

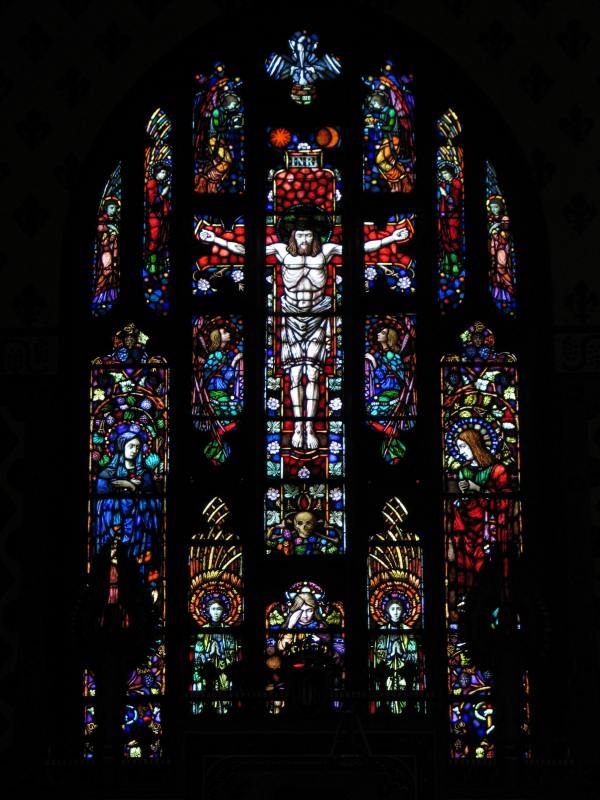

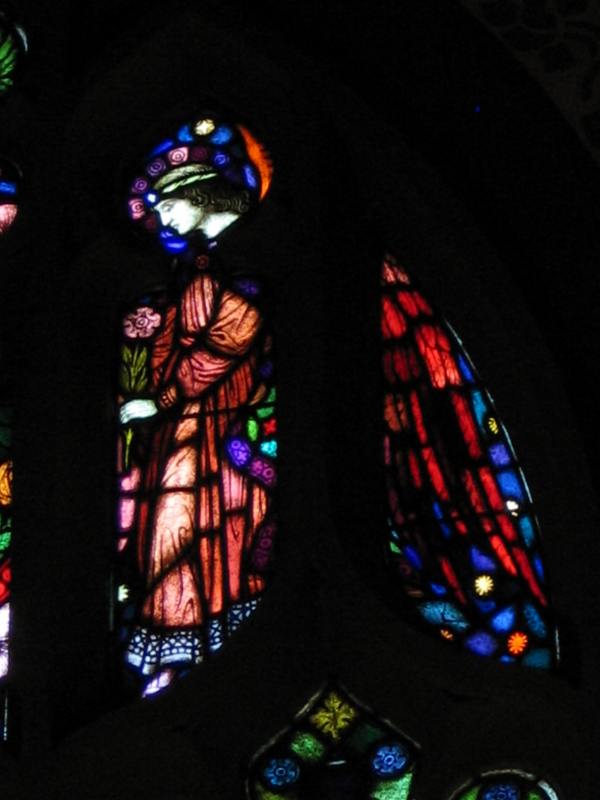

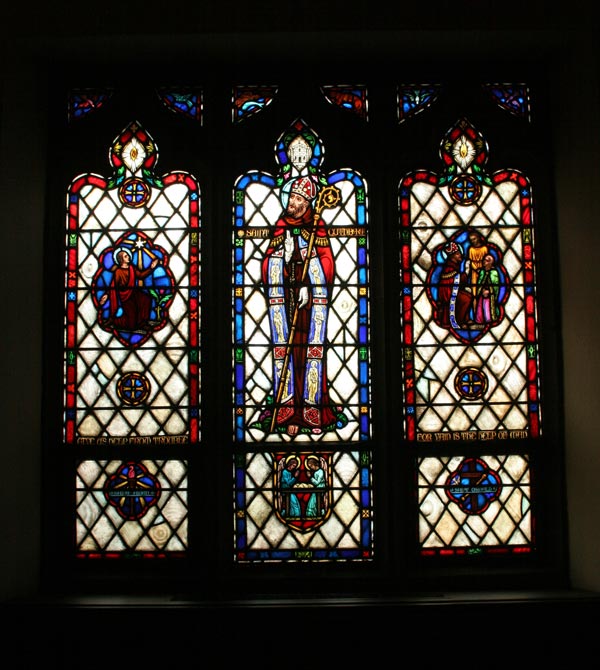

Howard Gilman Wilbert (1891-1966), Pittsburgh: Nave windows, from windows designed and made 1939-62 for the Episcopal Church of the Redeemer; E. Donald Robb, for Frohman, Robb & Little, architects

Photographs of stained glass windows by Glenn Lewis © 2009/glennlewisimages.com. Text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. Photograph of The Church of the Redeemer © 1998 William Rydberg PHOTON for Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

As the craftsman selects the pieces of colored glass and puts them together in various combinations, he becomes more and more fascinated by the infinite variety of effects to be obtained, and to have a profound love and respect for the material that makes this possible.

–Howard G. Wilbert

Despite its comparative youth—Pittsburgh’s Episcopal Church of the Redeemer was designed and built 1936-37—the building incorporates earlier structures erected after the parish was established in 1903. According to James D. Van Trump, the principal structure, a stucco building of 1913, was “turned around, set on new foundations, encased in Gothic stone work, and a stone tower was added.” The new building cradles the old. The Church of the Redeemer, in Jamie’s words, exhibits “a fineness of scale and proportion and an amiable forthrightness of aspect that make it one of the best things of its kind in Pittsburgh.” The same might be said of the stained glass windows, created over more than two decades by one craftsman, Howard Gilman Wilbert.

Wilbert was born in Pittsburgh and attended Stevenson Art School, operated by Horatio S. Stevenson, a respected Pittsburgh painter who had studied in New York and Paris, and became the first president of the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh in 1910. That same year Wilbert began an apprenticeship with Pittsburgh Stained Glass Studio (founded in 1904 and still in business). After serving in World War I, Wilbert worked with Charles J. Connick in Boston for over a year before returning to Pittsburgh and his old firm. He became a partner and served as chief designer for 35 years.

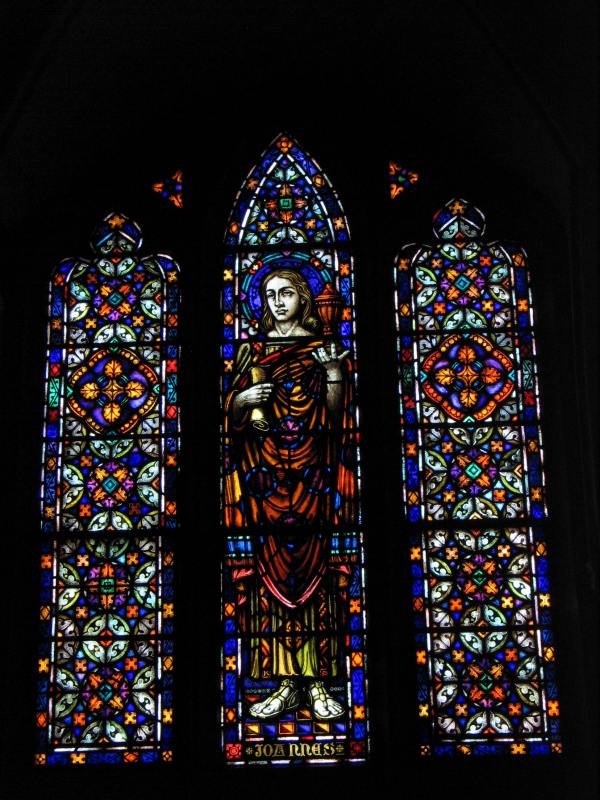

Wilbert was a parishioner at the Church of the Redeemer and he and the rector, Hugh S. Clark, planned the iconographic program for the windows, all of which Wilbert designed and made between 1939 and 1962. The nave windows depict Biblical figures, such as Saint John the Evangelist (shown here) and St. Joseph of Arimathea, and saints of the British Isles: S.S. Cuthbert (shown here), Aidan, Oswald, Columba, Finnian, Brennan, and Patrick.

Other notable Wilbert glass in Pittsburgh includes windows at the Church of the Ascension (1918), East Liberty Presbyterian Church (c. 1931-35), St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church (1961-62), and contributions to windows in the Hungarian and Russian Nationality Rooms and the Stephen Foster Memorial at the University of Pittsburgh.

One stained glass window in the Church of the Redeemer not by Wilbert is the sacristy window by Connick Associates of Boston in memory of Hugh S. Clark (1903-1992).

The architect of the Church of the Redeemer, E. Donald Robb (1880-1942), apprenticed with Theophilus Parsons Chandler and Cope & Stewardson in Philadelphia and worked in both the Boston and New York offices of Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson. (Robb prepared the presentation drawing for Bertram Goodhue’s First Baptist Church in Pittsburgh.) Robb left CG&F in 1911 to form Brazer & Robb [1911-14] with Clarence W. Brazer. Robb returned to CG& F in 1914. Sometime after 1918, Robb formed a partnership with CG&F employee Harry B. Little (1883-1944); they were joined by Philip H. Frohman (1887-1972). Frohman, Robb & Little is best known for completing the Washington National Cathedral.

Sources: Howard G. Wilbert, “Charles J. Connick: Stained Glass Craftsman and Friend,” Stained Glass 41 (Autumn 1946): 76-79. Hugh S. Clark, The Stained Glass Windows in the Church of the Redeemer Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, n.d.). James D. Van Trump and Arthur P. Ziegler, Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh 1967): 107-108.

Illustrations

- The Church of the Redeemer (1998)

- Saint John

- Saint Cuthbert

-

Henry Wynd Young (1874-1923), New York

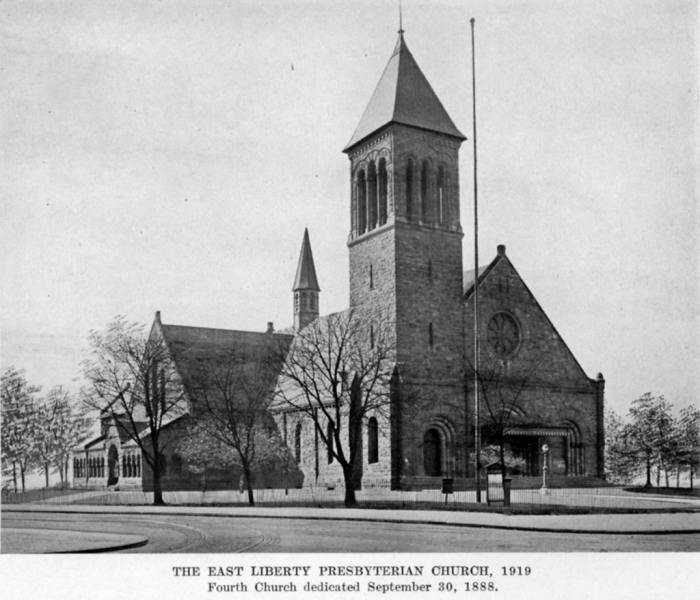

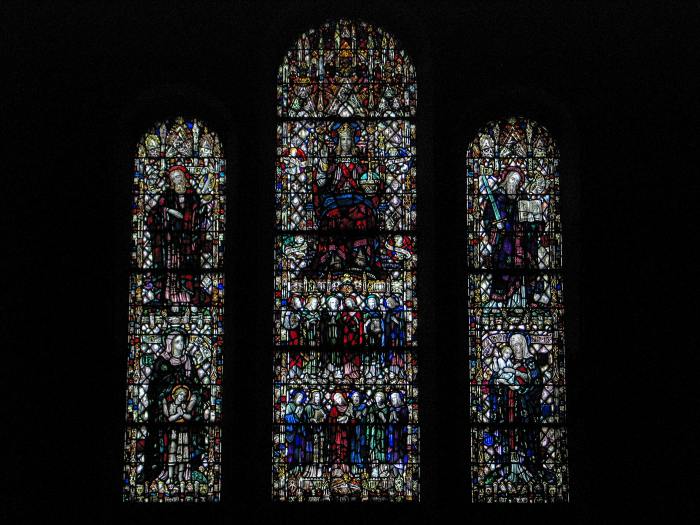

Henry Wynd Young (1874-1923), New York: “Christ Enthroned,” c. 1922, Chapel chancel window in East Liberty Presbyterian Church; Ralph Adams Cram for Cram & Ferguson. Window originally installed in a transept of the previous building, Longfellow, Alden & Harlow (1886-88), architects

Photograph of “Christ Enthroned” and text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

One of the finest stained glass windows in Pittsburgh, designed and made by one of the most gifted glass artists working in 20th-century America, is only intermittently visible. Located in the chapel of East Liberty Presbyterian Church, it is obscured by liturgical banners only removed for special occasions such as weddings, concerts, and funerals. The name of the window and its precise date are as yet unknown. For convenience sake we will call it “Christ Enthroned,” note that the design was exhibited in Pittsburgh in 1922, and that the window was installed in a transept in the 1888 church building, demolished in 1931 to make way for the current building designed by Ralph Adams Cram.

Scottish stained glass artist and historian Rona H. Moody has determined that Henry Wynd Young was born in Bannockburn, Scotland, in 1874, was living in Aberdeen by 1881, and attended evening classes at Gray’s School of Art there 1889-c. 1896. A decade later—a decade presumably spent working in glass firms (as yet unidentified)—Young arrived in New York on May 10, 1907; his wife Bessie and year-old son Henry Walter left Aberdeen and came to the United States, arriving New York on November 6, 1907. A second son, Alexander, was born in New York City in 1908. Young and his family settled in Brooklyn where he established his own business.

Young exhibited some of his designs at the Architectural League of New York in 1914. The following year he formed a partnership with G. Owen Bonawit (1890-1971). Fellow Scot John Gordon Guthrie (1874-1961) joined the firm that year and subsequently they were joined by Irish glazer Ernest Lakeman (1882-1948). The Bonawit & Young partnership dissolved in 1918. Young moved his residence to Hamilton, New York; he died there on December 25, 1923. Guthrie stayed on until 1925 and Lakeman operated Young’s glass shop for several years thereafter. According to the 1930 census, Bessie T. Young was president of the firm and Henry Walter Young worked there as a stained glass painter.

In 1919 Bertram Goodhue wrote of Young: “there is no doubt in my mind that he is far and away the best glass stainer we have.” Ralph Adams Cram thought so highly of Young’s work that he included him posthumously in his 1924 survey of the best stained glass firms then working in America. Windows by Young can be found, most notably, at St. Paul’s Chapel, Columbia University, the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, and St. Vincent Ferrer in New York City; Emmanuel Church, Newport, R.I.; Church of the Redeemer, Morristown, New Jersey; and East Liberty Presbyterian Church.

In 1922 Young participated in an exhibition of stained glass organized by Lawrence B. Saint (a Pittsburgh glass artist who established the Washington National Cathedral’s stained glass studio in 1928)—Stained Glass: Original Windows, Designs, Cartoons, Drawings of Medieval Windows, held November 13-December 16, 1922 at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh. One of the items Young exhibited was “Sketch design of transept, East Liberty Presbyterian Church, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” The finished window, left to right, shows Old Testament figures Elijah above and Hannah and her son Samuel below; Christ enthroned above the twelve apostles in the center; and, from the New Testament, St. Paul above and Mary and the infant Jesus below.

There is as yet no comprehensive assessment of Young’s work. The iconography and the colors of his windows evoke medieval English glass while displaying “a wry and sophisticated sense of character,” in James Sturm’s apt phrase. Young operated a small shop, assisted by a few gifted associates, a practice influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain. Charles J. Connick, educated and trained in Pittsburgh, advocated an Arts and Crafts approach in his Boston studio. He wrote of Young:

The late Henry Wynd Young re-created with sensitiveness and charm the forms familiar to students of fifteenth-century glass in England. He was searched out by appreciative architects and churchmen who were not satisfied by advertisers and salesmen. Through opportunities they gave him he has left us a few examples of exquisite windows . . . . He helped to make a place in America for the artist-craftsman who need not be heralded by salesmen and publicity agents.

Sources: Bertram G. Goodhue correspondence 1903-24, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts library, Columbia University. Ralph Adams Cram, “Stained Glass: An Art Restored; America’s Position in Bringing About a Renaissance of This Phase of Architectural Beauty,” Arts and Decoration 20 (February 1924): 11-13, 50. Charles J. Connick, Adventures in Light and Color (New York 1937): 176. James L. Sturm, Stained Glass From Medieval Times to the Present: Treasures to Be Seen in New York (New York 1982): 72. Special thanks to Peter Cormack, Rona H. Moody, and Wayne H. Kempton, Archivist, Episcopal Diocese of New York.

Illustrations

- East Liberty Presbyterian Church (1888-1931). Photograph taken from Georgina G. Negley, East Liberty Presbyterian Church (Pittsburgh 1919): following page 118.

- “Christ Enthroned”

-

George W. Sotter (1879-1953), Pittsburgh

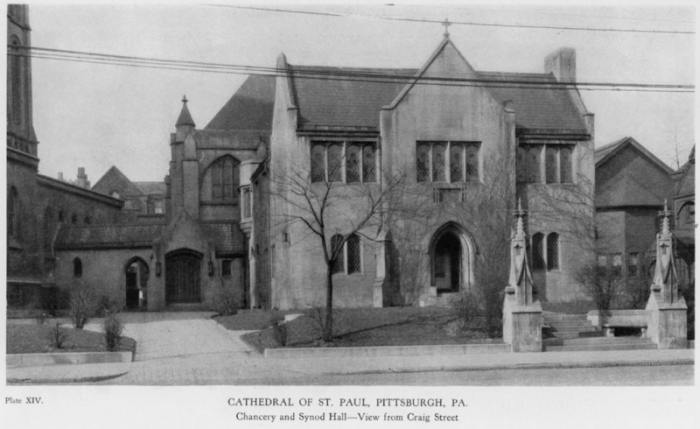

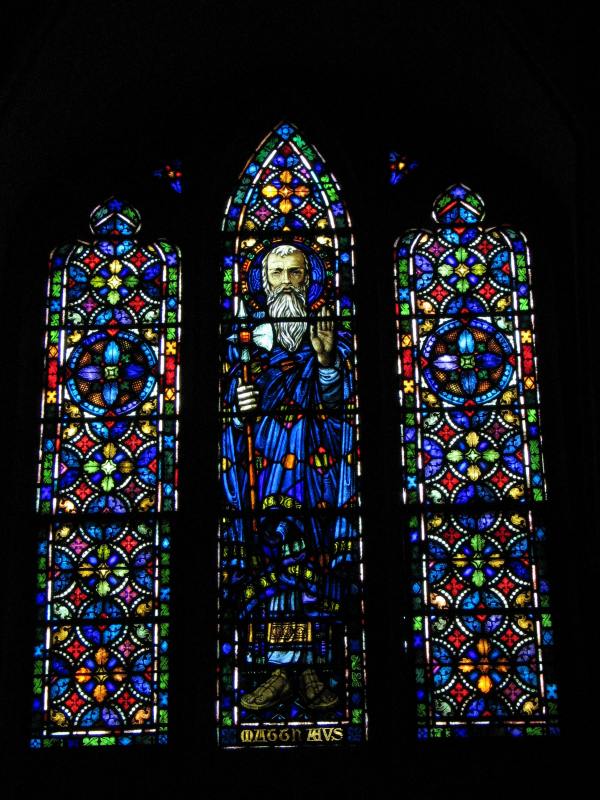

George W. Sotter (1879-1953), Pittsburgh: St. Matthew and St. John, 1914-15, Synod Hall; Edward J. Weber, architect

Photographs of St. Matthew and St. John and text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

The invention of opalescent glass and the “painterly” approach to glass windows that prized pictorial realism above all were largely byproducts of the prevailing “American Renaissance.” By 1910 the character of stained glass art in the United States had changed. Around 1900 Otto Heinigke of Brooklyn began combining native opalescent glass with traditional hand-blown antique glass, and revived leading as a technical and aesthetic component in window making. In 1902 Harry E. Goodhue, brother of architect Bertram G. Goodhue, revived medieval techniques and iconography in the first large all-antique glass window in the United States in Newport, Rhode Island; this was followed by a similar window designed and made 1904-05 by William Willet at the First Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh. Influenced by William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts movement, American glass artists came to appreciate the architectural character of windows as openings in the wall rather than as self-referential glass paintings. The purity of color and the architectural fitness of the medieval stained glass window was no longer viewed as primitive but was now seen as an appropriate and technologically sophisticated element in a new architectural language based on medieval forms, begun by H. H. Richardson and subsequently championed by architects Ralph Adams Cram, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, and other adherents of 20th-century American Gothic.

Heinigke, Harry Goodhue, and Willet had all been trained as painters before working with stained glass and they had tentatively made the journey from one medium to another. Their pioneering efforts made it possible for those in the following generation to more readily recognize that different techniques and approaches were required by the easel painter and the stained glass craftsman. Some artists found both worlds congenial.

George William Sotter was one such artist. Born into a Roman Catholic family in Pittsburgh, he apprenticed in several glass shops before studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia at the urging of Horace Rudy. In a memorial tribute to Rudy he recalled:

I had come under William Willet, and worked in four shops before meeting Rudy. I shall never forget how Rudy received me, looked at my paintings and gave me an opportunity to work with him. In glass as well as in painting he fed me with his enthusiasm to keep going and keep trying. He was always happy over any success that came to me. He gave and loaned me books, took me to plays . . . . He saw to it that I met all his friends,—Henri, Sloan and Redfield,—saw that I had a leave of absence to go to the Pennsylvania Academy. Then when I studied under Redfield, he extended my leave two more months.

Joan Gaul tells us that Sotter attended the Pennsylvania Academy 1901-02 and returned to Rudy Brothers in 1903. There he met Alice Bennet (1883-1967), who entered the Rudy shop as an apprentice in 1904; they married in 1907.

Sotter successfully—often simultaneously—painted, taught painting, and designed stained glass. He exhibited paintings at the Pennsylvania Academy, the Carnegie Institute, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, 1904, and the Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D. C. He was active in the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh (established 1910), participating in their annual exhibitions. He taught painting at Carnegie Institute of Technology 1910-1919 in Pittsburgh. He designed stained glass for Pittsburgh Stained Glass Company and Petgen Company, and he and his wife collaborated on stained glass projects.

Sotter’s first documented windows, installed in the Church of the Epiphany in Pittsburgh as part of a 1910 renovation supervised by architect John T. Comes, are simple, primarily geometric, and self-effacing. (Sotter has been credited with the original 1903 windows; these are not his work but were almost certainly made by Ludwig von Gerichten of Columbus, Ohio.) At least two churches from this period that had Sotter windows have been demolished, although his 1911 clerestory windows in Comes’ St. Gertrude, Vandergrift, survive.

Sotter’s first noteworthy stained glass windows are in the Synod Hall and Chancery building, adjacent to St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Cathedral, seat of the Pittsburgh Diocese. The windows, in place when the building opened April 12, 1915, include secondary windows in the library, offices, the auditorium stairway, and the impressive, almost life-sized twelve apostles who light the balcony in the auditorium. The Gazette Times described the twelve apostles:

The windows are so designed that the light from the outside filtering through their prismatic colors makes pure white light. The hall is not to be used every hour of the day, nor for reading, nor writing, nor for office purposes: hence very little natural light is required. The twilight of a clear day is perhaps the most favorable time for appreciating the amazing, deep, gem-like coloring of the windows. The tones are as rich and as soft as those of a Persian rug, and the black lead lines give a continual contrast to the glowing labyrinth of translucent jewels. The windows are 12 in number, each dedicated to an apostle, each twinkling with an almost barbaric burst of color.

Notable windows followed in the Diocese of Pittsburgh; in particular those at St. Agnes, 1917-18 (now the Carlow University chapel) and St. Paul of the Cross Monastery, 1919. In 1919, the Sotters moved to Holicong, Pa. in Bucks County. George Sotter painted (one of his paintings recently sold for $110,000) and the Sotters continued to create stained glass windows. A group of windows created for St. Canice Church in Pittsburgh c. 1930 has been reinstalled at St. Paul’s Cathedral, but the Sotters’ most notable achievement are the windows for Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church in Pittsburgh, designed and made between 1930 and 1954 and completed by Alice Sotter after her husband’s death in 1953.

Synod Hall was designed by Edward J. Weber (1877-1968). Weber apprenticed with architectural firms in Boston and studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He arrived in Pittsburgh c. 1906 and designed a substantial number of handsome schools (public as well as parochial) and ecclesiastical buildings and wrote about church architecture. George Sotter designed the windows for Edward Weber’s St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Cathedral, Wheeling, West Virginia.

Sources: “The Pittsburg Stained Glass Co.,” Up-Town, Greater Pittsburg’s Classic Section; East End, The World’s Most Beautiful Suburb (Pittsburgh Board of Trade, 1907), n.p. “Art.” The Index, 22 June 1907: 25. Lawrence B. Saint, “The Art of a Pittsburgher,” The Bulletin, 14 May 1910: 11. “Building a Triumph,” Gazette Times, 12 April 1915. George Sotter, “J. Horace Rudy, Master of Friendship,” Stained Glass 35 (Spring 1940): 32-33. Jean M. Farnsworth, “Biographical Sketches of Stained: 45, 53, 55.

Illustrations

- Synod Hall. Photograph taken from Edward J. Weber, Catholic Ecclesiology (Pittsburgh 1927): Plate XIV.

- St. Matthew

- St. John

-

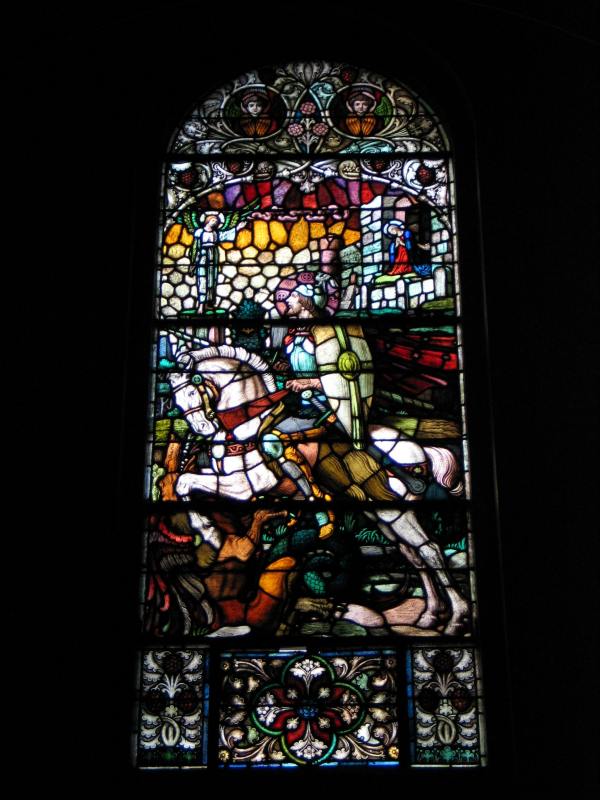

Leo Thomas (1876-1950) for George Boos (1859-1937), Munich, Germany

Leo Thomas (1876-1950) for George Boos (1859-1937), Munich, Germany: Chancel window and detail of transept angel, 1910-11, St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, Butler, Pa., John T. Comes, architect; “Tu Es Petrus” and St. George, 1911-12, St. George’s Roman Catholic Church; Herman J. Lang, architect

Photographs and text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

“Munich glass”—stained glass made in Munich, Germany (then the kingdom of Bavaria)—originated during the reign of Ludwig I of Bavaria (1786-1868) who sought to turn his capital into an unrivaled center of German art and culture. The leading Munich glass firms were Mayer & Co., founded by Josef Gabriel Mayer and later led by his son Franz, and F. X. Zettler (the firms later merged; Mayer & Co. is still in business). Jean Farnsworth tells us that Mayer & Co. was founded in 1847 to make ecclesiastical furnishings. Josef Gabriel’s son-in-law, Franz Xavier Zettler, organized the firm’s glass workshop in the 1860s, then founded his own glass firm in 1870. Both companies quickly won royal and papal endorsements. Mayer & Co. and Zettler opened sales offices in the U.S.A. in 1888 and c. 1902 respectively. Their earliest documented glass in the Pittsburgh Diocese dates to 1890.

The artistic language of Munich glass owed much to the revival of religious painting, especially fresco painting, in Germany early in the 19th-century. Kathleen Curran notes: “The fresco revival had its origins in Rome in 1812, when the young Peter Cornelius sought out Friederich Overbeck and joined the Brotherhood of St. Luke. Cornelius’s special contribution to that movement was the renewal of fresco painting in the tradition of the Italian Renaissance masters, especially Masaccio, Raphael, and Michelangelo.” Ludwig I sent German art and German artists to the United States. Curran observes that St. Vincent’s Benedictine Abbey in Latrobe, Pa, forty miles west of Pittsburgh, received some 300 paintings from King Ludwig, and Munich-trained artists like William Lamprecht taught fresco painting at St. Vincent; he and pupils like Bonaventure Ostendarp and Raphael Pfisterer painted religious art in Roman Catholic churches throughout the Mid-Atlantic and Mid-Western states during the second half of the 19th century.

Although Munich windows were made of traditional hand-blown antique glass, both Munich windows and American opalescent windows typically eschew the flatness and emphatic leading of medieval windows in favor of an idealized naturalism and spatial realism. Wealthy Protestants might prefer opalescent windows, which were complicated and expensive to make, but Munich glass windows could be imported as art, i.e., glass “paintings” and—exempt from a high tariff on imported “raw” glass—cost less than opalescent windows and windows made in America using imported glass. Although often derided by English glass artists as too pictorial, and viewed as an economic threat by American glass firms, the broad aesthetic appeal, economic advantage, and papal approval made Munich glass windows the overwhelming choice among Roman Catholics in the United States.

George Boos of Munich began his career at Mayer & Co., then established his own firm c. 1880. Shortly thereafter, his 7-year-old nephew Leo Thomas, born in London, moved to Munich. Leo studied at the Munich Arts & Crafts School and the Museum of Fine Arts. He traveled to Italy, Tunis, and, in 1906, England. Jean Farnsworth observes: “Leo sometimes developed designs for windows based on cartoons in the Victoria & Albert Museum, including those of Edward Burne-Jones.” She further cites a 1912 German stained glass publication that “refers to George Boos’s ‘modern’ aesthetic, characterized by many small pieces of glass in a dense network of leads, suggesting the studio’s interpretation of the Neo-Gothic.” While Boos glass in Philadelphia is “more conservative, and in keeping with the techniques of the Munich pictorial style: relatively large pieces of glass and minimal emphasis on the leads” she also observes that “much of [the firm’s] work . . . is particularly notable for its emotionally charged, non-idealized depictions of the sacred stories [and] lacks the Raphaelesque sweetness so typical of the Munich style.”

Between 1910 and 1912 Leo designed over 60 stained glass windows made in Germany by the Boos firm for two new Roman Catholic churches in the Diocese of Pittsburgh: St. Paul’s, Butler, dedicated September 10, 1911, and St. George’s, Pittsburgh, dedicated July 7, 1912.

St. Paul’s, Butler, was designed by John T. Comes (1873-1922), one of Pittsburgh’s leading Roman Catholic church architects. It was the almost certainly Comes, who described St. Paul’s windows as:

the realization of old ideals worked out with modern means…. The windows were made by the firm of George Boos in Munich, and to Leo Thomas a nephew of Mr. Boos is due all credit for their beauty of color and design. Messrs. Boos and Thomas have been comparatively unknown in this country heretofore, but it is safe to say that work like that which we are considering will soon win for them an international reputation.

The chancel window and an angel from the tracery of the transept windows at St. Paul’s, and two of the twelve nave windows at St. George’s (now St. John Vianney Parish) are illustrated. The windows exhibit a stylized two dimensionality, with backgrounds and ornamental sections composed of “many small pieces of glass in a dense network of leads.” In these windows, the flat, heavily leaded neo-medieval meets the abstract to create strikingly “modern” images, akin to the work of contemporary Secessionist designers in Austria and Hungary.

Comes described St. Paul’s as English Gothic and designed all the furnishings. The chancel was painted by the Christian Art Guild of Pittsburgh. The metalware was made by the St. Dunstan’s Guild of the Society of Arts & Crafts, Boston, and the Birmingham [England] Guild of Handicraft.

St. George’s Church is located in Pittsburgh’s Allentown neighborhood—The Pittsburgh Catholic called the building “an adaptation of the German Romanesque style to suit modern needs”—was designed by Herman J. Lang (born c. 1885), a native of Hesse, Germany, who came to Pittsburgh in 1901 to join his brother, Edmund (1875-1955), in the architectural firm of Edmund B. Lang & Brother. The brothers designed Roman Catholic churches in Pittsburgh together through 1910 and separately thereafter. Edmund moved to Los Angeles after 1918; Herman Lang maintained his office in suburban Carrick where he lived with his wife and three sons, and where his best-known church building, St. Basil, is located.

Sources: John T. Comes, et al., A Notable Work of Christian Art: St. Paul’s Church Butler Pa., Dedicated Sept. 10 MCMXI. “Solemn Dedication, Grand Diocesan Event: St. George’s Church Allentown,” The Pittsburgh Catholic, 6 June 1912. John T. Comes, Catholic Art and Architecture (Pittsburgh 1920). Jean Farnsworth, et al., Stained Glass in Catholic Philadelphia (Philadelphia 2002), 135, 152-153, 180, 196, 354-355, 381, 395, 427-428. Kathleen Curran, The Romanesque Revival (University Park, Pa., 2003): 75, 84-91. Elgin Vaassen, Bilder Auf Glass (Munich/Berlin 1997), 257-258, 350. Thanks to Jean Farnsworth, Gail Campbell, Diocesan Archivist Burris Esplen, Dr. Elgin van Treeck-Vaassen, and Leo Thomas’ granddaughter, Barbara Deeken.

Illustrations

- St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, Butler, Pa.

- Chancel window

- Tracery angel, transept window

- St. George’s Roman Catholic Church, Pittsburgh, Pa

- “Tu Es Petrus”

- St. George