Category Archive: PHLF News

-

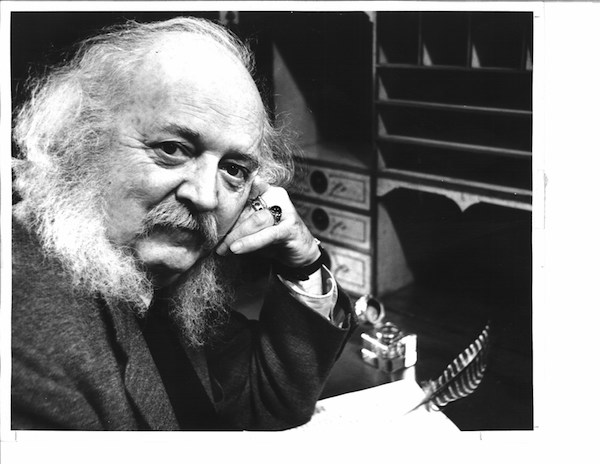

The Personal Papers of James D. Van Trump

The strongest impression I got about Jamie as a Pittsburgh figure was from the letters and cards he received during his time in the hospital after his accident in 1978. He received over two hundred cards from people he had never met, who knew him from his appearances on the Al Julius KDKA television program and from his public appearances at various events. I even saw a letter referring to him as “Mr. Pittsburgh,” in reference to his knowledge of local history and architecture. ––Emily Dahlin, Duquesne University intern archivist

PHLF Co-founder James D. Van Trump

Thanks to the dedication and expertise of Duquesne University graduate student Emily Dahlin, various personal correspondence, memoranda, and miscellaneous ephemera have been added to PHLF’s James Van Trump Collection. Jamie Van Trump (1908 – 1995) co-founded PHLF in 1964 and served as its first architectural historian. The materials that Emily organized date from 1948 to 1991, with the bulk of them being from 1970 to 1991.

Emily Dahlin’s description of her experience in organizing Jamie’s personal correspondence follows:

“As part of Duquesne University’s Public History program, I completed an archival internship at PHLF from the fall of 2015 through mid-January 2016, working on the personal correspondence of Co-founder James Van Trump. I was drawn to interning at PHLF because I am interested in architecture and historic preservation, and I had hoped to work with archival materials relating to Pittsburgh architecture and prior PHLF preservation projects. My primary goal in completing this internship was to be able to work on an archival project at its earliest stages and see it to completion. I had never had the challenge of working on an unprocessed collection from the beginning of the process, and I was eager for the opportunity to process the Van Trump collection.

“The correspondence and personal papers were housed in five large boxes and were, I soon found out, completely unorganized and unprocessed. The correspondence ranged in date from 1941 to 1991, and had sat untouched in a storage unit until very recently. The boxes contained a wide variety of items, including letters and memoranda, greeting cards, postcards, legal documents, photographs, newspaper clippings, and various ephemera. This task required that I read every individual piece of correspondence, which was the main reason why the project was so time-consuming. After several weeks, I was able to select over two hundred pieces of correspondence for preservation by PHLF, and recommended several other documents for donations to other institutions, most notably a collection of material related to the Second World War, which PHLF has donated to the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial in Oakland.

“On a few occasion during my internship, I was asked to assist with educational walking tours for elementary and high school students, and for adults. I found these experiences to be valuable, as they allowed me to experience how PHLF works with the community and acts as a public voice for history and preservation. I learned a lot from my experience on the education tours about how community outreach works and the different ways in which history and architecture can be incorporated into a number of different programs and school lessons. Overall, I feel that my experiences at PHLF had a very positive impact on my understanding of the public history field, and I am grateful to have had the experience.”

-

In Memoriam: Jonathon Hulton Bridge

Hulton Bridge over the Allegheny River. Photo by Greg Pytlik, Pytlik Design Associates

The Jonathon Hulton Bridge over the Allegheny River between Oakmont Borough and Harmar Township was demolished on Tuesday, January 26. Until its closure, the landmark Hulton Bridge was the oldest active vehicular bridge over the entire length of the Allegheny River.

Constructed in 1908-09, the Hulton Bridge was technologically innovative. The bridge had a total length of 1,544 feet and a main span of 505 feet, one of the fiftieth longest simple truss spans in North America. Its Pennsylvania truss type was first developed by the Pennsylvania Railroad as a modification of the smaller Parker truss to be capable of spanning longer distances. The Hulton Bridge’s approach spans were shorter Parker trusses, each approximately 260 feet in length.

Serving as the link between Oakmont and Plum and Route 28 and the Pennsylvania Turnpike on the opposite side of the Allegheny River, the bridge was a frequent traffic bottleneck, necessitating its replacement by the new four-lane steel girder bridge. In 2009, students at Carnegie Mellon University studied retaining the bridge for pedestrian use, but doing so would have conflicted with the replacement bridge.

The Allegheny County Roads Department was formed in 1895, and it became the Allegheny County Department of Public Works in 1924. The department started rather small, and its first bridges were short spans over small streams. For example, an early County stone arch still stands near the Hulton Bridge at the intersection of Freeport Road and Powers Run Road, though it has been bypassed. As development spread beyond Pittsburgh and as automobiles became important, County government became involved in designing and owning roads and major bridges. Previously, privately owned companies had designed and owned major roads and bridges and had operated them as toll facilities.

The Hulton Bridge was Allegheny County Department of Public Works’ first river crossing. The Public Works Department kept growing, and was soon responsible for just about every major river bridge in Pittsburgh. It was not until the late 1950s that the Pennsylvania Department of Highways began to construct river bridges in the area. Later, the State began to take ownership of several of the former County bridges, including the Hulton Bridge.

The unique truss bridge had a majestic appearance, and it will be missed. Days before demolition, many Oakmont residents––and bridge admirers from elsewhere––were walking through the snow to take final photos of the memorable Hulton Bridge. The last four photos show the bridge on January 31, 2016, several days after demolition.

-

Landmarks Preservation Resource Center Events

We resume our programming at the Landmarks Preservation Resource Center—744 Rebecca Avenue, Wilkinsburg, PA 15221—with the first of a six-part demonstration workshop by Regis Will, a woodworker and master craftsman, who specializes in house carpentry and wood restoration.

We resume our programming at the Landmarks Preservation Resource Center—744 Rebecca Avenue, Wilkinsburg, PA 15221—with the first of a six-part demonstration workshop by Regis Will, a woodworker and master craftsman, who specializes in house carpentry and wood restoration.This year, Regis will offer six classes—one, every other month—touching on varying aspects of woodworking. His hands-on workshops will now take a three-hour window in order for him to focus and apply his teaching skills on specific details of the craft. His first workshop on Saturday, January 16, 10:00a.m.—1:00p.m., will be an introduction to woodworking hand tools. Other workshops will include sessions on sharpening edge tools; saws and the skill of sawing; planes, flattening and squaring wood, and a comprehensive session on creating basic joints.

Also in January, we will continue our screening of documentaries on architecture, history, public policy and planning of cities, with a two-part documentary on the architectural history of Paris, on Tuesday, January 19, 6:00p.m.—7:30p.m., and Thursday, January, 21, 6:00p.m.—7:30p.m.

Also in January, we will continue our screening of documentaries on architecture, history, public policy and planning of cities, with a two-part documentary on the architectural history of Paris, on Tuesday, January 19, 6:00p.m.—7:30p.m., and Thursday, January, 21, 6:00p.m.—7:30p.m.Join us for these and other lectures, workshops, seminars and community symposia, as we continue growing our programming at the Landmarks Preservation Resource Center (LPRC). Take a look at our events calendar at www.phlf.org to see upcoming LPRC and other educational events including city and neighborhood walking tours and special events in 2016.

All programming at the LPRC is FREE to PHLF members.

Non-members: $5

Click here to renew your membership or Join now! RSVPs appreciated to all events to Mary Lu Denny: Marylu@phlf.org or 412-471-5808 ext. 527

For more information or to suggest a potential topic/idea for presentation at the LPRC, please contact, Karamagi Rujumba: Karamagi@phlf.org or 412-471-5808 ext. 547.

-

Thank You, Interns

Max Adzema, who graduated from the University of Pittsburgh in December 2015, and Emily Dahlin, a student in Duquesne University’s Public History program, successfully completed volunteer internships with PHLF in the Fall of 2015.

Max Adzema

“We are grateful to Max and Emily for helping with tours, various research projects, and several Poetry and Art workshops and publications,” said PHLF Executive Director Louise Sturgess. “In addition, Max provided invaluable help in editing the second edition of the August Wilson guidebook, and Emily sorted through and organized the personal papers of James D. Van Trump, PHLF’s co-founder.”

Each intern commented on their experiences with PHLF:

“As someone who loves Pittsburgh this internship has been an incredibly rewarding experience, opening the door to further opportunities and interests in local history and architecture. I have been continually surprised by the passion, drive, love, knowledge, and dedication that PHLF staff members have shown while pursuing the goals of building pride in and preserving our beautiful city. Thanks for the many wonderful experiences!” ––Max Adzema, University of Pittsburgh (History of Art & Architecture/Museum Studies)

Emily Dahlin

“Overall, I found my internship at PHLF to be an educational, challenging, and valuable one. Through my archival projects and my observations of educational programming, I have learned much about the city of Pittsburgh, historical architecture, and archival work. I feel that fulfilling this internship had a very positive impact on my ability to perform as an archivist and has done much to further my educational and professional goals.” ––Emily Dahlin, Duquesne University (Public History)

-

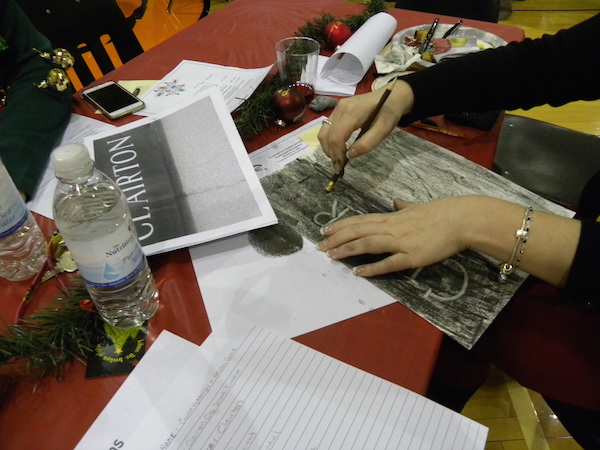

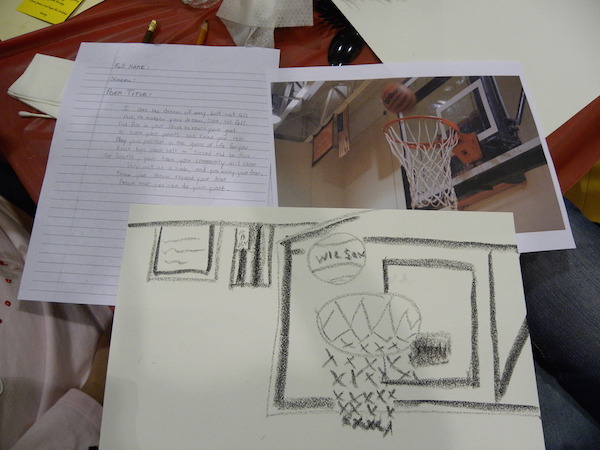

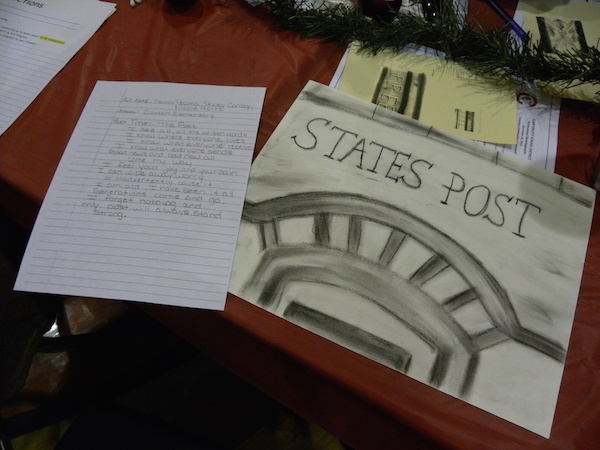

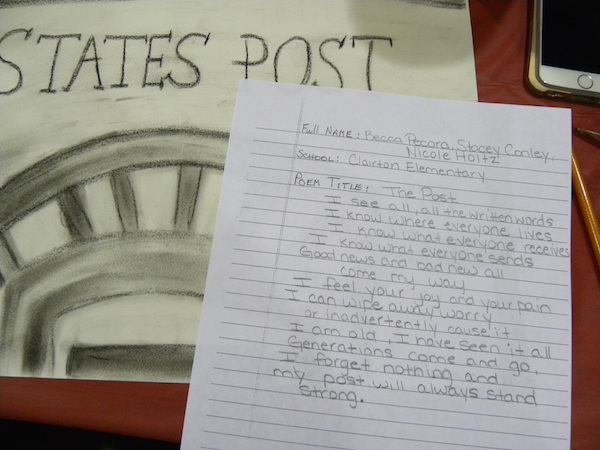

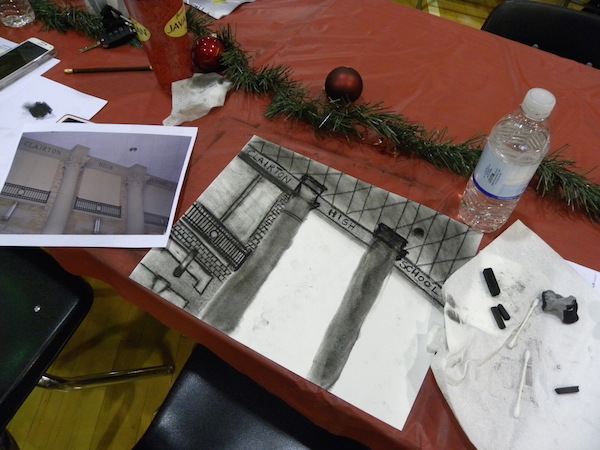

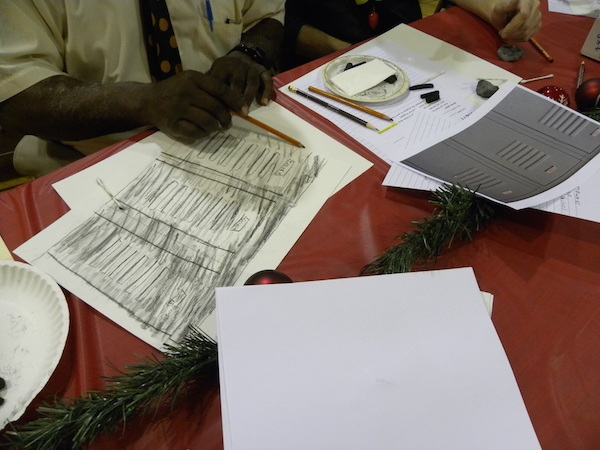

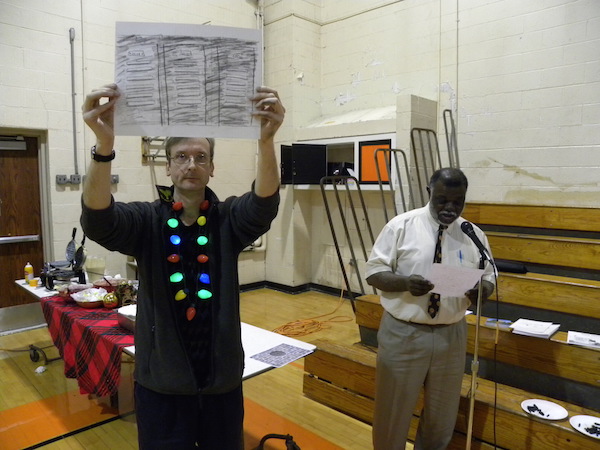

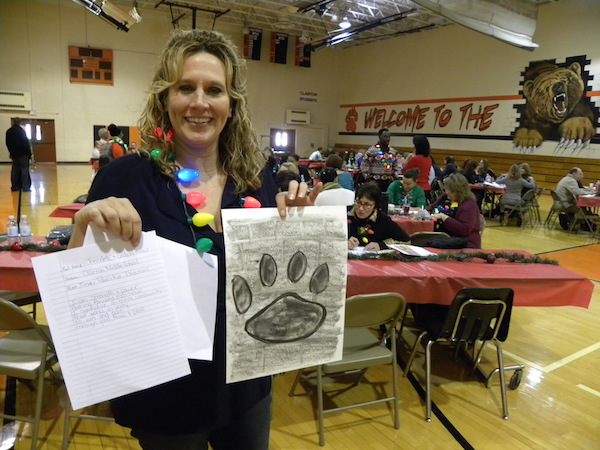

Contrasts in Clairton: Education Versus Demolition

A long-vacant commercial building on St. Clair Avenue in Clairton was demolished in December 2015.

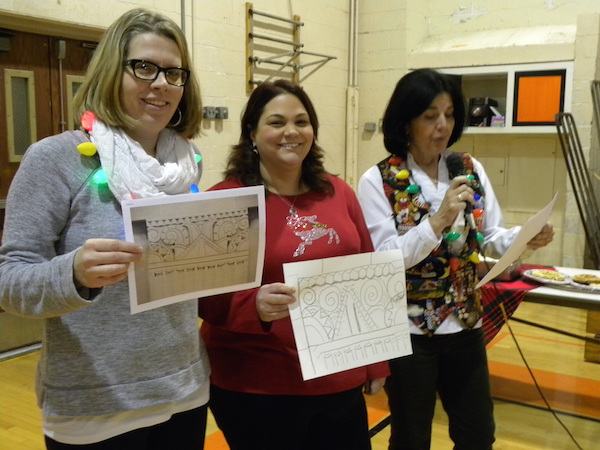

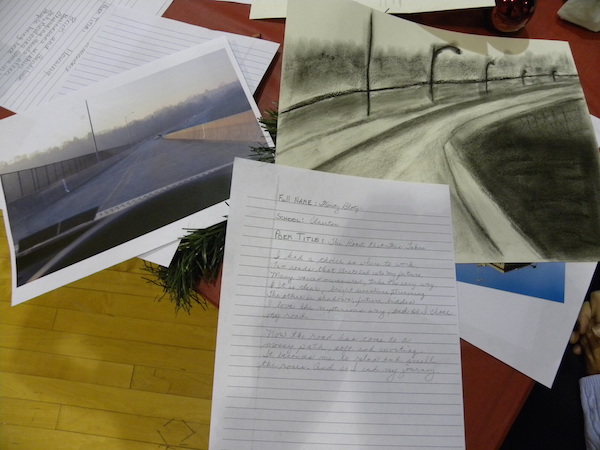

On the morning of December 16, 2015 two noteworthy events were occurring simultaneously in Clairton: PHLF Executive Director Louise Sturgess was involving 100 teachers from the Clairton School District in a Poetry and Art workshop at Clairton Middle/High School on Waddell Avenue. In the gallery below, see photos from that inspiring event. Just a block away, a historic building on St. Clair Avenue was being demolished.

“When I left the school I was startled to see this contrast,” said Louise. Inside the school, teachers from all grade levels were sketching architectural details from their school or community landmarks and were composing poems about those details that made you care about the buildings. Outside, the stone façade of a long-vacant commercial building on one of Clairton’s main streets was being knocked down.”

A major article in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in November 2015 described the community development challenges facing Clairton. PHLF’s survey of 1980 identified more than 50 significant architectural landmarks in Clairton that could provide the foundation for economic renewal.

-

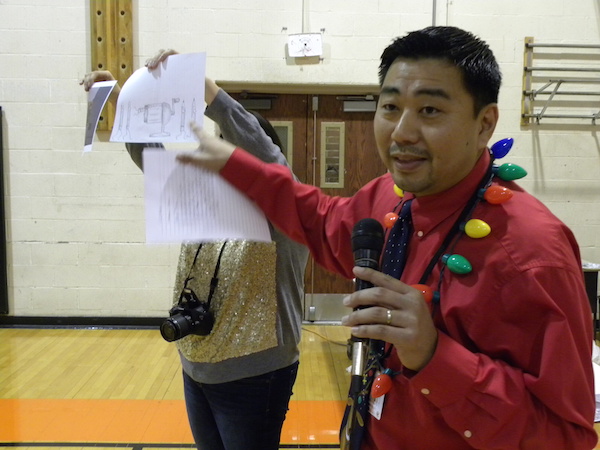

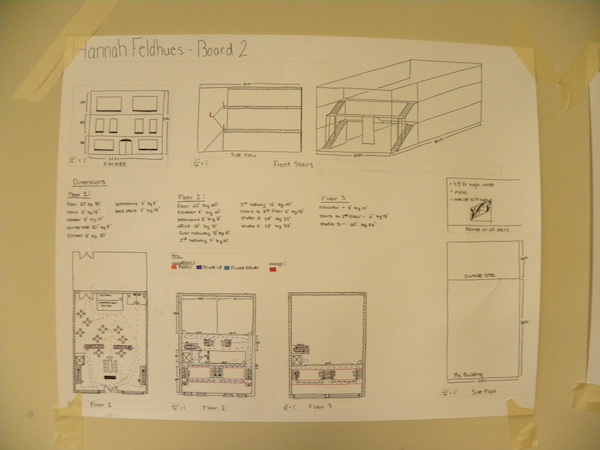

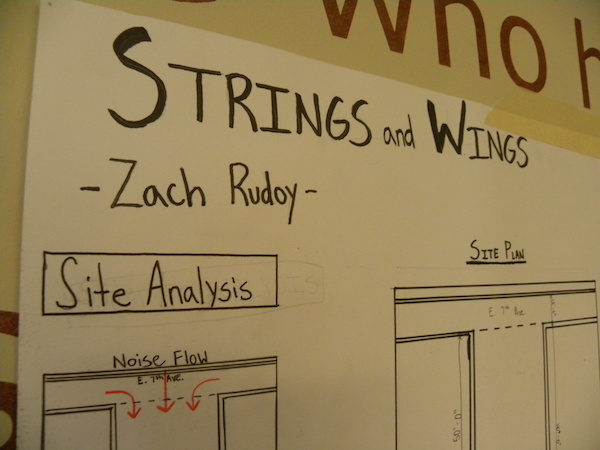

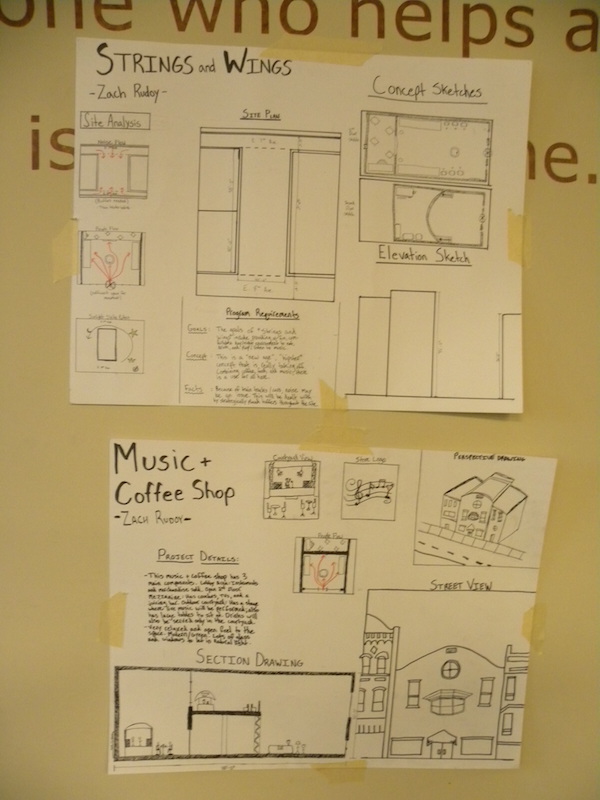

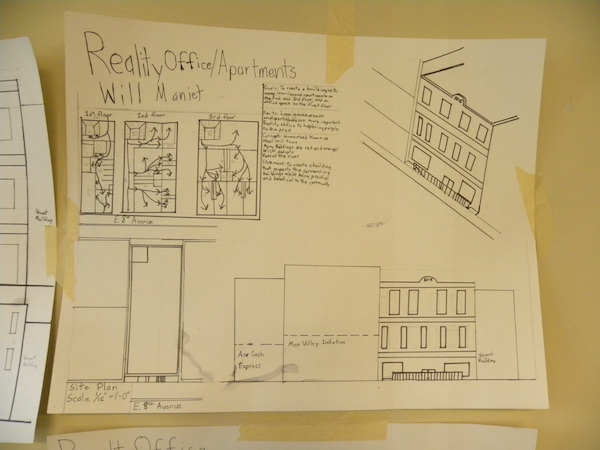

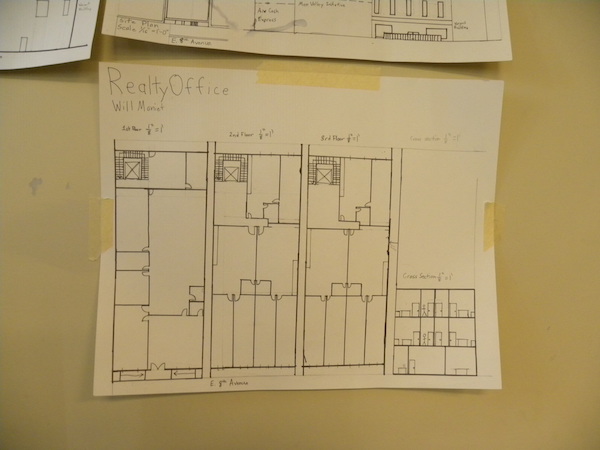

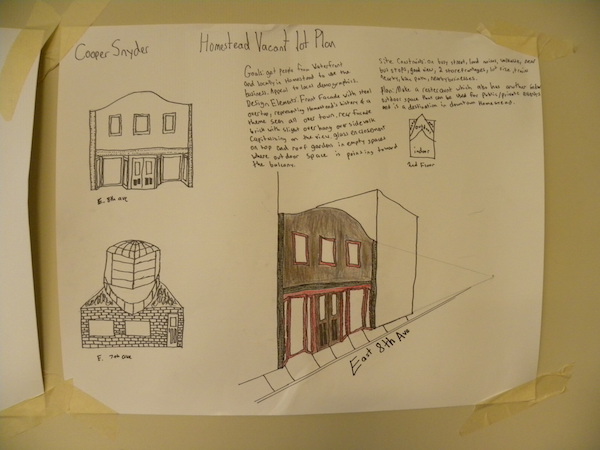

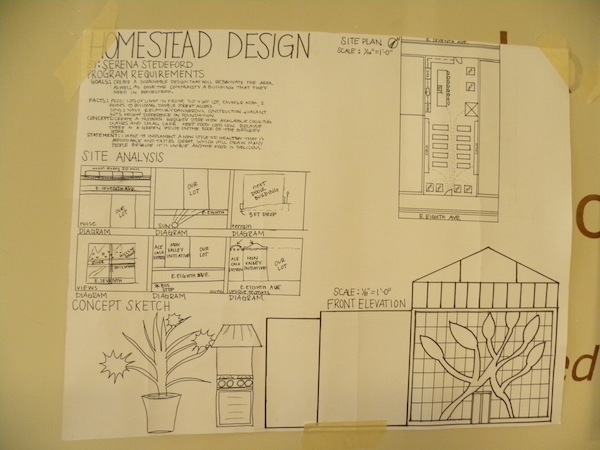

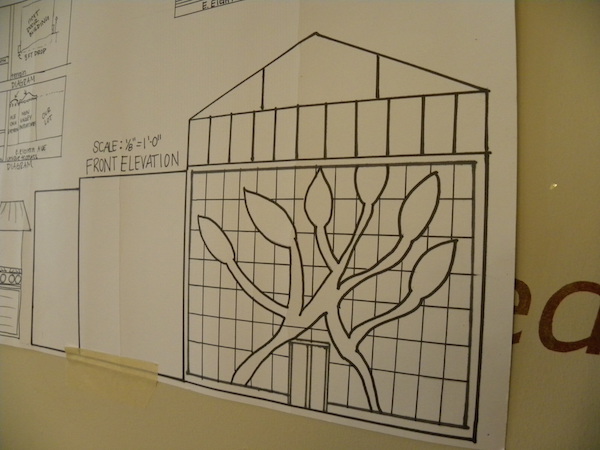

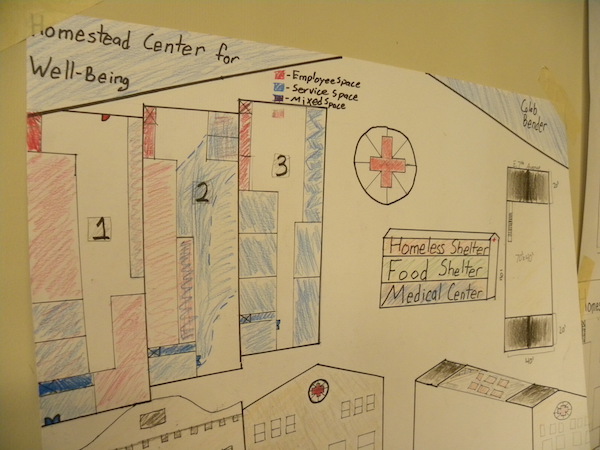

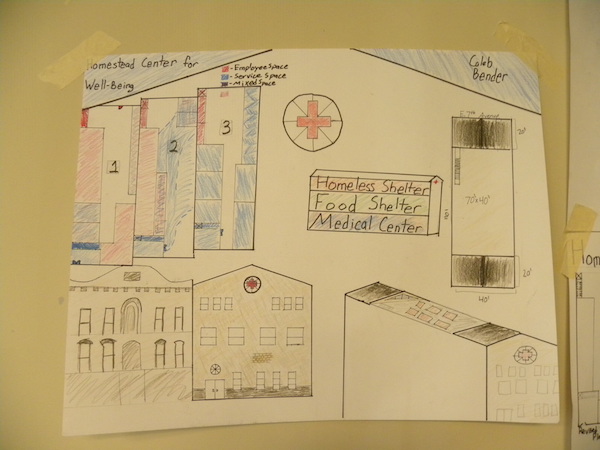

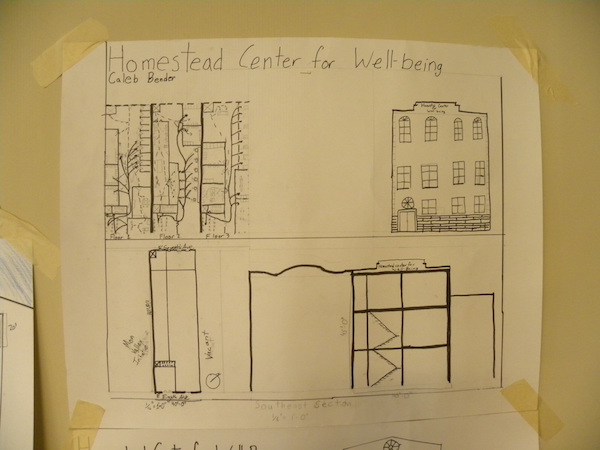

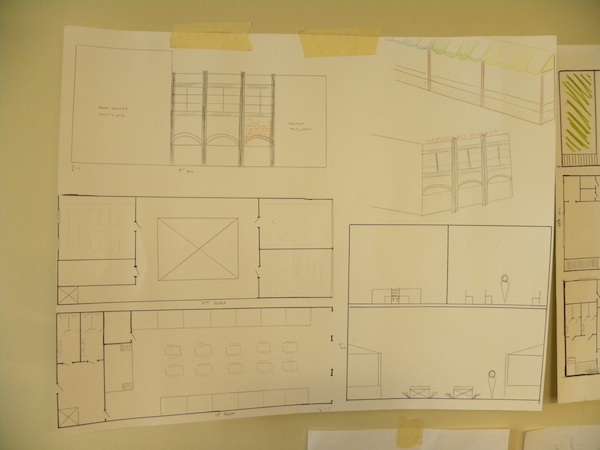

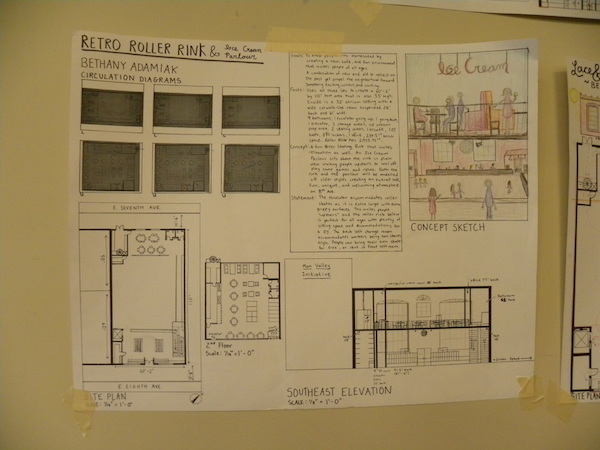

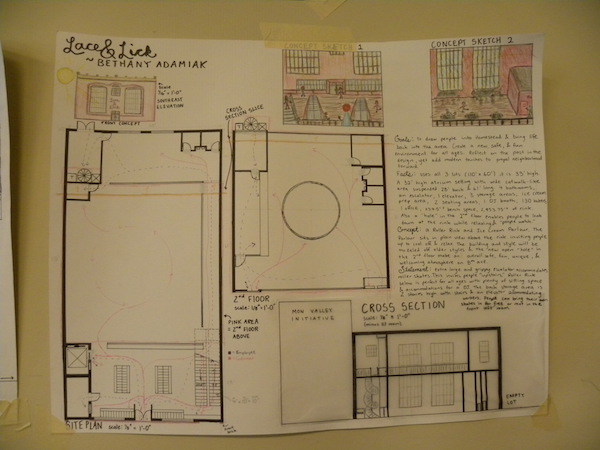

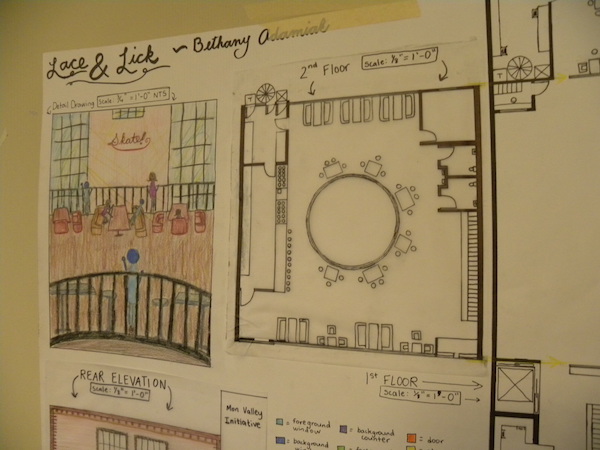

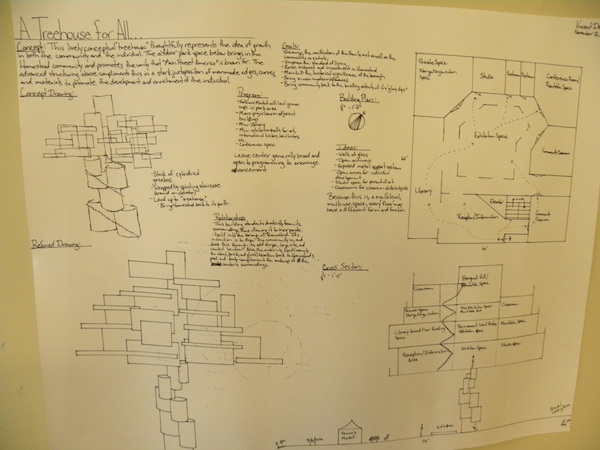

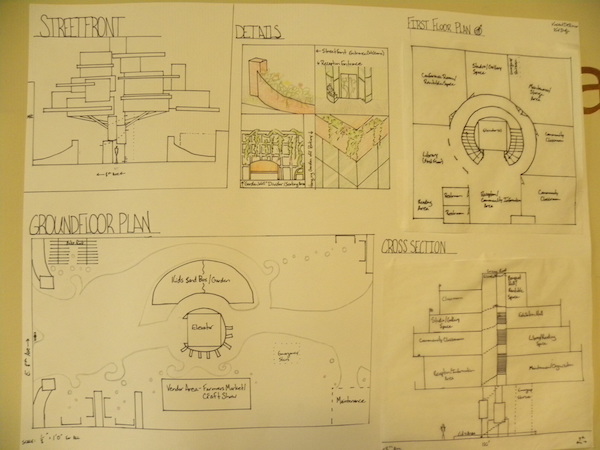

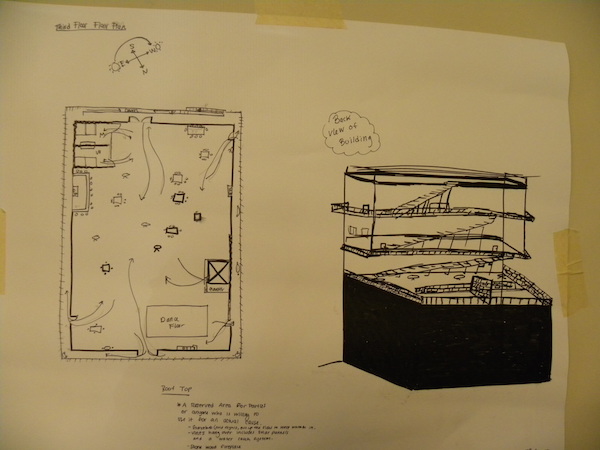

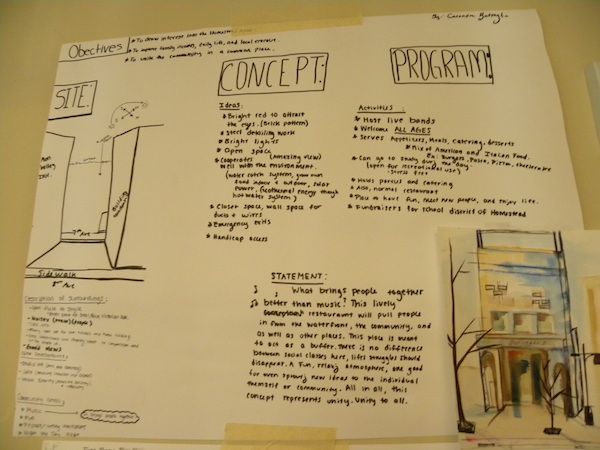

Apprentices Present Vacant Lot Designs

A vacant lot in Homestead was the site of a real-world design challenge for high school apprentices in architecture.

“I got to go through the architectural process in a practical, real-world scenario. I got to view historic architecture and learn about the value of preserving it.”

“It helped me understand the life and schooling of an architect. It helped me decide if this is something I would want to do with my life.”

“This program taught me everything I know so far about architecture. It taught me so much I now feel confident combining it with my mathematical and artistic skills to start my career path in college this upcoming year.” ––Comments from Apprentices, Fall 2015

PHLF’s longest-running education program is the Architecture Apprenticeship, offered through the Allegheny Intermediate Unit. High school students who are interested in architecture, urban planning, and historic preservation may apply to the Allegheny Intermediate Unit (AIU) and are selected to participate in five, full-day sessions that PHLF plans and leads, September through December.

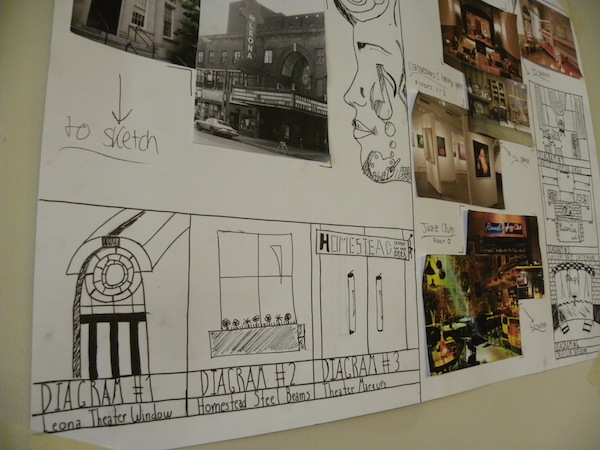

This year, educator Samantha Carter from CMU’s School of Architecture and architect Paul Tellers assisted PHLF’s Louise Sturgess in teaching the program. “The students were introduced to the design process,” said Paul, “and were able to tour Homestead, CMU, and downtown Pittsburgh, where they visited Urban Design Associates.”

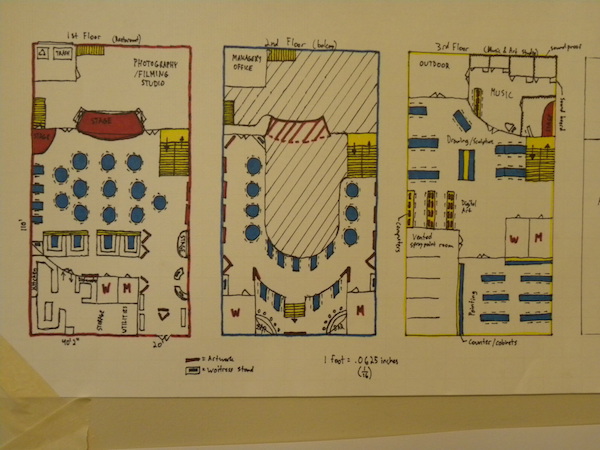

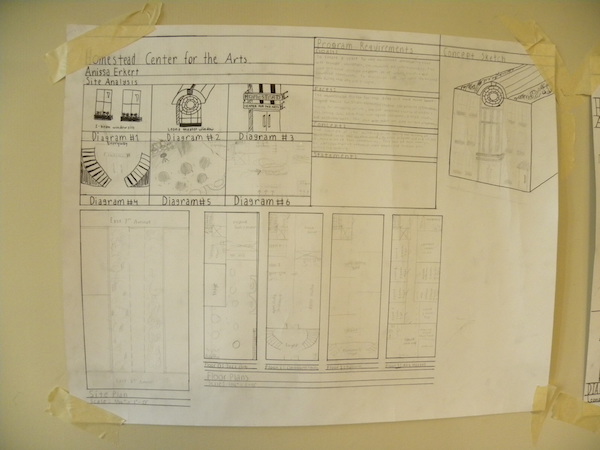

The apprentices developed their design ideas for a vacant lot at 307-09 East Eighth Avenue in Homestead with guidance from CMU’s School of Architecture and professional architects. On December 9, they presented their ideas to a jury of professionals including Borough Manager Ian McMeans, Mon Valley Initiative Representative Stephanie Eson, and architect Raymond Bowman.

Ideas included a dance studio and cafe; music and coffee shop (“Strings & Wings”); realty office and apartments; a restaurant and event space; a building devoted to food, music, and art; an arcade and ice-cream parlor with mixed-income apartments; a community center for the arts; a grocery store with a rooftop greenhouse; a medical center, food shelter, and homeless shelter; an indoor market with a rooftop garden; a roller skating rink and ice cream parlor; a community learning center, including library, studio, and gallery spaces; and a restaurant and entertainment venue.

“The students invested a great deal of thought and effort in developing their design ideas,” said Louise Sturgess. “Any one of the concepts would be wonderful to develop and would benefit the Homestead community.”

See the various design ideas the students presented in the photo gallery below.

-

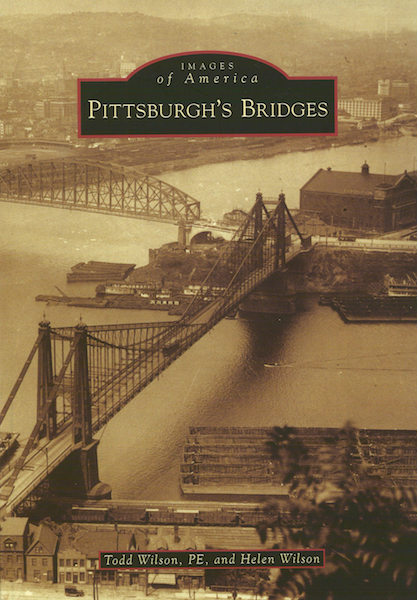

PHLF Trustee Co-Authors Book on Bridges

Thank you for your work in teaching kids to love history, especially Pittsburgh history. Who knows, one day one of them might write a book. ––Inscription from Todd Wilson to PHLF’s Executive Director Louise Sturgess, in her copy of Pittsburgh’s Bridges

Pittsburgh’s Bridges

Todd Wilson, PE, and Helen Wilson are the authors of Pittsburgh’s Bridges ($21.99), the newest book in Arcadia Publishing’s Images of America series. Following a refreshing introduction discussing Pittsburgh’s bridges in the context of its topography and the historical development of transportation systems in the region, Pittsburgh’s Bridges launches into eight chapters with concise introductions: Point Bridges, Allegheny River Bridges, Monongahela River Bridges, Ohio River Bridges, Ravine Bridges, City Beautiful Bridges, Railroad Overpasses, and Footbridges. In 200 photo captions, the authors discuss the design, construction, and at times, demolition of 144 historic and extant bridges in our “City of Bridges.” They clearly explain how different bridge structures work, and describe how the design of Pittsburgh’s bridges often resulted in brilliant construction innovations and unique partnerships between engineers, architects, and the Municipal Art Commission.

Pittsburgh’s Bridges can be ordered from Arcadia Publishing or from any major online bookseller such as amazon.com, and is also available in local bookstores. Or you may order the book from the authors for the retail price of $21.99 plus $3.00 for postage and handling (book rate).

About the authors:

Todd Wilson is a trustee of PHLF and professional engineer at GAI Consultants, Inc. He first connected with PHLF in first and third grades when he entered the Bridge-Building Contest in our Hands-on History Festival at Station Square. Years later, he was selected as one of three scholarship recipients in 2002, based on his essay on Pittsburgh’s bridges, that ended with the statement: “I can safely predict that my whole life will be devoted to bridges or roads, especially in the Pittsburgh region.” Todd graduated from Carnegie Mellon University in 2006, organized the first and second annual Historic Bridge Conferences here in Pittsburgh in 2009 and 2010, and was named one of Pittsburgh Magazine’s “40 Under 40” honorees in 2011.

Todd’s mother, Helen, also is devoted to Pittsburgh history. A member of both PHLF and the Squirrel Hill Historical Society, Helen has researched and written about the significance of the Mary S. Brown Memorial-Ames United Methodist Church and Turner Cemetery at 3424 Beechwood Boulevard. A graduate of Carlow University, she worked as a teacher, editor, and writer for the Pittsburgh Public Schools.

The authors collaborated to produce a well-researched and fascinating illustrated history of a defining aspect of Pittsburgh. At a time when many historic bridges are endangered, this book informs the reader of the importance of the bridges that we cross every day, and by documenting their significance, encourages a preservation ethic.

-

Book Review: Pittsburgh Architecture in the Twentieth Century

By Peter Cormack

The Journal of Stained Glass, XXXVIII, 2014 [British Society of Master Glass Painters], 178-179.Albert M. Tannler. Pittsburgh Architecture in the Twentieth Century: Notable Modern Buildings and Their Architects. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 2013. Softcover, 276 pp., 321 col. and b/w ills. ISBN 978 0 9788284 9 3, $18.95.

The work of architectural historian Albert M. Tannler, Historical Collections Director of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, is well known to readers of this Journal. As the devoted chronicler of the city’s architectural heritage, he is something of a civic treasure worthy of statutory designation himself. The latest title from his pen (or computer) is a cornucopia of informative discussion and description, accompanied by numerous fine illustrations, revealing the remarkable wealth of modern buildings in this great American conurbation.

In the minds of many people who do not know the city, Pittsburgh’s identity is still indelibly marked by its industrial past, tellingly illustrated by a late 19th-century view in the ‘Eve of Modernism’ section of Tannler’s Introduction. The present-day city, however, has lost the pall of filthy smoke and soot overhanging and coating its buildings, as almost all the traditional manufacturing has disappeared or been transformed. Nowadays, one is very aware of Pittsburgh’s beautiful setting of surrounding hills and the fine rivers that run through it, and the city’s architecture has few rivals in the USA for historical interest and aesthetic distinction. Tannler’s focus is on the successive stages of post-1900 architectural modernism, broadly defined. He describes the buildings, gives fascinating short biographies of their designers and often adds socio-economic details of their up-and-down history to the present day. In his introductory writing, he also charts the dissemination of American and European modern styles through publications and influential institutions like the Pittsburgh Architectural Club.

The book covers all types of building. Glancing through the many illustrations, one is immediately struck by the diverse cultural influences prevalent among Pittsburgh’s architects––a natural consequence, of course, of its polyglot immigrant population. The Hungarian-born Titus de Bobula designed several churches that clearly demonstrate his awareness of Art Nouveau and Secessionist trends in central Europe. The First Hungarian Reformed Church (1903-4) in Hazelwood has echoes of Medgyaszay[1] in its rounded fenestration and determination to avoid historicist traits; it also has charming stained glass roundels (by an unidentified designer-maker), depicting heroes and heroines of Hungary’s Protestant history. De Bobula, Tannler tells us, was later under FBI surveillance and was described by his biographer as a ‘notorious architect and arms merchant’.

Leaded-light glazing is a conspicuous feature of much of the pre-First World War domestic architecture, sometimes in simple quarry patterns but occasionally in an idiom akin to Frank Lloyd Wright’s work. The Lydia A. Riesmeyer house (architect Richard Kiehnel, 1914) has particularly Wrightian windows and leaded light-fittings, partly in citrus-coloured opalescent glass combined with textured whites. Interior photographs show how such detailing was very much part of a total decorative scheme that embraced all exterior and interior elements. The suburban borough of Thornburg can boast a number of houses in which this kind of coordinated design approach was capably designed by architects influenced by Midwest, California and other regional idioms. S. T. McClarren’s splendid 1132 Lehigh Road is a later version of the 19th-century ‘shingle style’, given a quasi-expressionist sweep of horizontality and beautifully positioned on a sloping wooded site.

The Austro-German influence is a leitmotif throughout much of this book, evident in Kiehnel’s 1916-31 Greenfield School, the main doorway of which ‘quotes’ Herrmann Billing’s Mannheim Museum. As almost always happened in such cases, however, the European source gains a convincingly American identity in its new setting, aided by more ample contextual space and a generally more expansive scale for the buildings themselves. Tannler devotes a section of his book to the so-called Art Deco style (more properly called ‘Moderne’) with a description of one notable interior scheme given prominence. This is the Omni William Penn Hotel’s banquet room (1929) by the great Viennese-American designer Joseph Urban. It has all the luxuriant splendour of 1920s slient-era Hollywood move décor, blended with Wiener Werkstätte sophistication (Urban was the Vienna group’s US representative). Urban’s scheme has been conserved in recent years but, as the photographs show, it would benefit from a comprehensive restoration to reveal fully its original impact.

Appropriately, since Tannler has done so much to examine the topic in a scholarly way, a chapter on ‘American Gothic 1905-38’ is at the heart of the book. As well as featuring the masterpieces of Ralph Adams Cram (Calvary Church, 1905-7, Holy Rosary, 1926-31 and East Liberty Presbyterian, 1930-35), and of Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (First Baptist Church (1909-11), which all have powerful glazing schemes by Charles Connick and his contemporaries, he illustrates and discusses Carlton Strong’s equally powerful Sacred Heart (1926-54), with glass by George and Alice Sotter, and (Welsh-born) William P. Hutchins’s St James Catholic Church, Wilkinsburg. The later is notable for its eighty windows by Wright Goodhue. Stained glass was recognized as an essential component of Modern Gothic buildings, even in secular structures such as Charles Z. Klauder’s soaring Cathedral of Learning on Pittsburgh University’s campus, built in the 1930s. Along with Klauder’s Stephen Foster Memorial and Heinz Memorial Chapel, it features glazing by Charles Connick. The Heinz windows, intricately blending biblical and American historical imagery, are in themselves well worth a pilgrimage to Pittsburgh.

Glass, although rarely if ever stained or leaded, increasingly dominates much of the later architecture illustrated, as the International Modern Movement increasingly imposed its ‘functional’ ideology and rejection of tradition on Pittsburgh’s building styles. Those in sympathy with this merciless reduction of an art form to a branch of engineering science may find much to please them in the illustrations and scholarly descriptions. Your reviewer’s tastes and prejudices will be all too evident, and it will be best of conclude this review by praising unreservedly the author’s exemplary research and fluent writing, and the equally exemplary enterprise of his publisher, PHLF, which has done so much to preserve and celebrate the architectural heritage of one of America’s most historic and beautiful cities.

[1] István Medgyaszay (1877-1969), Hungarian architect, trained at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna.