Latest News

-

Newcomers Explore Historic Neighborhoods

PHLF’s March programming with the Jewish Family & Community Services’ Newcomers Crew included using PHLF’s exploratory book, “Neighborhood Stories, Including Mine,” and virtual exploration of Pittsburgh’s Strip District, with students adding their own store to the National Register Historic District. “Victor’s House of Pizza and Lego’s” is pictured here.

The Jewish Family & Community Services’ Newcomers Crew is a virtual after-school mentoring program for recently resettled refugee youth in Pittsburgh. JFCS staff, mentors, and participants share information about their respective cultures, learn about America, Pittsburgh, and their countries of origin.

Sarah Greenwald, PHLF co-director of education, introduced participants to their new hometown through several activities. Club members and their mentors used Neighborhood Stories, Including Mine, recently published by PHLF, to learn more about their family, neighborhood, and community. Then, they explored the Strip District with Sarah, who shared information about its historic landmarks, family-owned businesses, and cultural diversity. Club members then worked with their mentors to add a business to the Strip based on their culture. They envisioned Pizza, Legosã, specialty bakeries, clothes, and grocery stores, among other ideas.

With PHLF, JFCS Newcomers Crew members also explored Pittsburgh’s Market Square, Forbes Avenue and Wood Street area, hearing from the local and woman-owned business Boutique La Passerelle, thanks to owner Adele Morelli. Additionally, club members learned more about the rich history of “Mystery Manor,” the National Negro Opera House in Homewood. Music and poetry came alive for participants in new ways through this particular historic structure and the rich legacy of Mary Cardwell Dawson. Inspired by Mary Cardwell Dawson’s story, some members created short poems in their native language, while others composed original music lyrics.

Each of these activities gave club members a sense of belonging in Pittsburgh. “I am always inspired by these club members,” said Sarah. “We learn from them as much as they learn from us. In the process, we all foster the sense that saving and sharing the historic fabric of our communities is important for our future.”

PHLF thanks the McSwigan Family Foundation Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation for supporting its place-based education programs.

-

15 Years of Our “Building Pride, Building Character” EITC Program

This year, our “Building Pride, Building Character” program is being offered in remote and virtual formats. This program teaches Pittsburgh Public School students about Pittsburgh’s history and architecture, and the people who work to improve our communities.

This spring, our fifteenth year of place-based education programs with Pittsburgh Public School students continues, with the creation of videos so this popular program can be experienced virtually. “We are also arranging virtual discussions with City Council representatives, working with SLB Radio Productions to record neighborhood stories written by students, and providing a series of PDFs based on our Career Awareness posters, and working with SLB Radio Productions to record stories written by students,” said Education Advisor Louise Sturgess.

PHLF released its first educational video on February 15 to a group of fifth-grade teachers in the Pittsburgh Public Schools. The 26-minute video, “The Bigham House on Mt. Washington: A Pittsburgh Connection to the Underground Railroad,” includes a walk through the woods and a tour of the mansion built in 1849 by abolitionist Thomas Bigham. Architect David Vater, a resident of Chatham Village, joined Louise Sturgess in narrating the video, and Chatham Village’s Board of Directors gave special permission so filming could take place inside the Bigham House. After watching the video, students from Pittsburgh Whittier completed writing prompts describing times in their lives when they felt free, and students from Pittsburgh Minadeo discussed how the video reinforced some of the experiences they had read about in the book, “The Road to Freedom.”

On February 23, PHLF facilitated a virtual conversation between Ms. Dulak’s third-grade students from Pittsburgh Roosevelt and Blake Plavchak, Chief of Staff for Councilman Anthony Coghill. Mr. Plavchak listened attentively to the students as they shared their ideas about what needs to be improved in Carrick and what is wonderful about their neighborhood. He told the students they were “completely accurate” in the concerns and attributes they noted, and encouraged them to keep talking with their elected officials. He appreciated how much they cared about their neighborhood and encouraged them to stay involved.

This program is made possible through the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development’s Educational Improvement Tax Credit (EITC) program. We are grateful to Dollar Bank for contributing recently and to seven corporate donors who contributed between November and December 2020. Donations from the following are underwriting our “Building Pride, Building Character” virtual programming with the Pittsburgh Public Schools through mid-June:

Lead

- First National Bank of Pennsylvania

Major

- The Buncher Company

- Dollar Bank

- PNC Bank

Patron

- Frank B. Fuhrer Wholesale Company

- Hefren-Tillotson, Inc.

- MaherDuessel, CPA

- Pickands Mather & Company

This program also receives foundation support from the:

- McSwigan Family Foundation Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation.

-

Society of Architectural Historians Grant to Support Education Programs

A Legacy in Stone & Song brings to life the architecture and history of the National Negro Opera House and other significant African-American landmarks in Pittsburgh. After touring these places virtually, students will complete creative projects inspired by these landmarks.

The Society of Architectural Historians has awarded the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation a $5,000 grant to fund programs for students from two Pittsburgh public schools to explore the architecture and history of the National Negro Opera House in Pittsburgh’s Homewood neighborhood.

The grant, made possible by the Society’s American Architecture and Landscape Field Trip program, together with funding from the McSwigan Family Foundation Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, and PHLF, will fund this educational program and other significant African-American sites in Pittsburgh including the New Granada Theater, Crawford Grill, August Wilson House, and August Wilson African American Cultural Center.

The story of each of these places is important in the history of our region and our nation and will be shared by the people who know them best. After a virtual tour, Pittsburgh Public School students will develop inspiring creative projects based on these significant African-American landmarks.

The SAH American Architecture and Landscape Field Trip grant recognizes the value of our Legacy in Stone and Song field trip program. Every place has a story, and the National Negro Opera House (NNOH) is especially noteworthy. This Queen Anne style house was included on the list of America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places by the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 2020.

Owned by William “Woogie” Harris, the house served as a home for the National Negro Opera Company, the nation’s first permanent all-Black opera company, led by the indomitable Madame Mary Cardwell Dawson. It also served as a temporary haven for national luminaries in entertainment and sports, many of whom were barred from white accommodations when traveling in Pittsburgh. Today, the National Opera House survives as the physical embodiment of Pittsburgh’s vibrant African American heritage.

Our organization’s education programs are always in need of your help! To support this program, please click HERE, and direct your contribution to “Education Programs.”

-

NEW! Virtual K-12 Walking Tours Now Available

PHLF Education is offering two NEW virtual student walking tours, in addition to virtual tours of its many in-person tours. Pittsburgh’s Hill District explores the legacy of August Wilson through Pittsburgh’s Hill District, and Pittsburgh’s Innovators looks at the inspiring people whose places in our city are named for them.

PHLF Education is excited to announce that we are now offering two new virtual tours in addition to virtual tours of our popular in-person student tours. Thanks to open-source mapping technology (Google Maps), PHLF staff and docents can lead participants along a tour route in real-time, as if walking on the street, but within the space of a computer screen. The laminated historical images that enrich our in-person tours continue to provide context and evidence of change over time to the tour, and our conversations with learners will remain as engaging as ever. PHLF is grateful to the McSwigan Family Foundation Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation whose support of its educational programs this year is helping underwrite the development of these new initiatives. Keep reading to learn more about our new and existing offerings, and how to schedule yours today!

Pittsburgh’s Hill District

Inspired by August Wilson’s work, and using PHLF’s guidebook August Wilson: Pittsburgh Places in His Life and Plays, students explore landmarks of Pittsburgh’s Hill District, learning about the neighborhood’s history and the influence Pittsburgh had on the playwright’s work. This tour also comes with a complimentary copy of the guidebook for your classroom library, along with a digital copy of PHLF’s African American Legacy in Allegheny County: A Timeline of Key Events.

Pittsburgh’s Innovators

Pittsburgh’s history is intertwined with the history of many of our nation’s innovators in science, the arts, sports, philanthropy, and more. Their legacy lives on in the historic places around us––the many bridges, buildings, parks, and other structures bearing their names. This tour explores the determination and hard work of several of these pioneers through the places named for them––people like Andy Warhol, Rachel Carson, Roberto Clemente, HJ Heinz, and others. Along the way, students will “travel” across several historic bridges and explore Pittsburgh’s downtown and North Shore neighborhoods.

In addition to these tours, educators can also schedule a virtual tour of any of our traditional in-person tours. Search for Downtown Dragons and Other Creatures Carved in Stone; or travel the world in just a few blocks on our Strip District Stroll; match colorful architectural details to correct buildings and learn about the history of the North Side on our North Side’s Historic Neighborhoods tour––whatever your classroom needs, we have the tour to match!

Let us plan your field trip for any number of students (grades 2 and above) who want to explore the architecture and history of downtown Pittsburgh or of a local neighborhood. We have over 40 years of experience in planning school field trip tours—and many creative ideas. Click here to schedule a tour. Don’t see a tour that fits your classroom needs? Email co-director of education Sarah Greenwald sarahg@phlf.org to tailor a tour.

-

Now Offering Virtual Architectural Tours

A combination of navigating streets on Google Maps, live narration by docents, and a slide presentation of supplemental material creates virtual versions of our beloved architecture tours. Shown here: a screen shot of a virtual tour of Carnegie, Pennsylvania, in November 2020.

We are delighted to announce that we will resume offering tours of Pittsburgh’s extraordinary architecture, which have been a mainstay of our education program for decades, this month. Our staff and dedicated docents would love to be outdoors with you— even in the cold weather —after so many months of confinement. However, in respect of Allegheny County’s public health guidelines for tackling the Covid-19 pandemic, we will instead offer live virtual tours.

Our virtual tours will be offered via Zoom Conference. Thanks to open-source mapping technology (Google Maps), docents can lead participants along a tour route in real time, as if walking on the street, but within the space of your computer screen. The laminated historical images that bring texture to our in-person tours also are shown in our virtual tours, as interjections of PowerPoint slides in the docents’ live narrative. Through the chat function in Zoom Conference, participants can engage with the docents and each other, much as they would on the street.

The result is a true multimedia presentation that allows participants to enjoy architecture tours from the comfort of their own homes. In fact, comfort is the operative term. As docent and former PHLF staff member has Karen Cahall pointed out, “on virtual tours, we can avoid things like bad weather, uneven or narrow sidewalks, and noise from traffic that sometimes challenge us on in-person tours.”

Google Maps also provides views that can’t be seen on in-person tours, by allowing us to scroll up a building to see details, zoom out for an aerial view, and travel farther than our feet could normally carry us in a single hour.

“We are truly excited to be able to offer tours again,” said Tracy Myers, co-director of education at PHLF. “I don’t believe any of our counterparts are doing tours in this way, and we’re eager to see how participants react to them. We’ve had to re-think each tour a little bit to accommodate the format, and as in every tech-enabled activity, there are occasional glitches. Our docents are working hard, though, to create authentic experiences, to remind us all why we love Pittsburgh’s architecture and history.”

Registration for tours will open on Saturday, December 5, and must be completed online. The fee is $7.50. For additional information, and to register, go to www.phlf.org/events.

-

Concrete Bridges of the Steel City

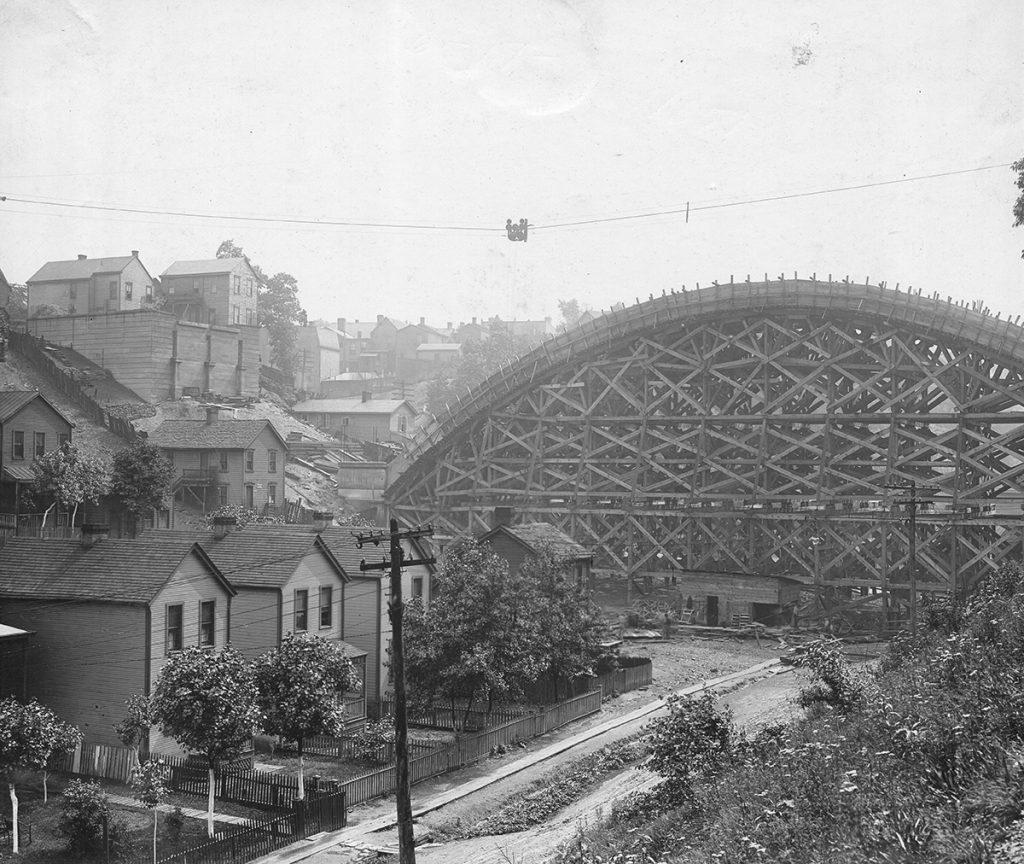

Construction of the Meadow Street Bridge in June 1910, with wooden falsework towering over the valley and the concrete arch starting to take shape. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

By Todd Wilson

While Pittsburgh may be known as “The Steel City,” many beautiful and significant concrete bridges were built here. Concrete is a rock-like mixture of fine and coarse aggregates (sand, gravel, stone) pasted together with a binder made up of Portland cement and water. Replacing natural cement, Portland cement (named for its resemblance to Portland stone from the Isle of Portland in England) is made from limestone, clay, and gypsum.

Portland cement was patented in 1824 and first manufactured in America in Lehigh County in 1871. As with stone structures, concrete is strong when compressed, but it is much weaker when being pulled apart in tension. A few concrete arch bridges started to be built in America in the 1870s, though it was not until steel reinforcement began to be added to concrete to withstand tensile forces starting around 1890, that the true potential of concrete structures could start to be realized.

The first large-scale concrete arch bridge was Luxembourg’s 1904 Pont Adolphe, with open spandrel walls and a 278-foot main span. Impressed, Philadelphia built a similar bridge in 1908, the Walnut Lane Bridge in Fairmount Park, having a 233-foot main span. Adorned with City Beautiful embellishments, it showcased how concrete could be used as an architectural material especially appropriate for parklike settings. The soaring arch avoided the need for intermediate supports infringing into the valley below, and using concrete instead of stone allowed for a more economical bridge with a longer span.

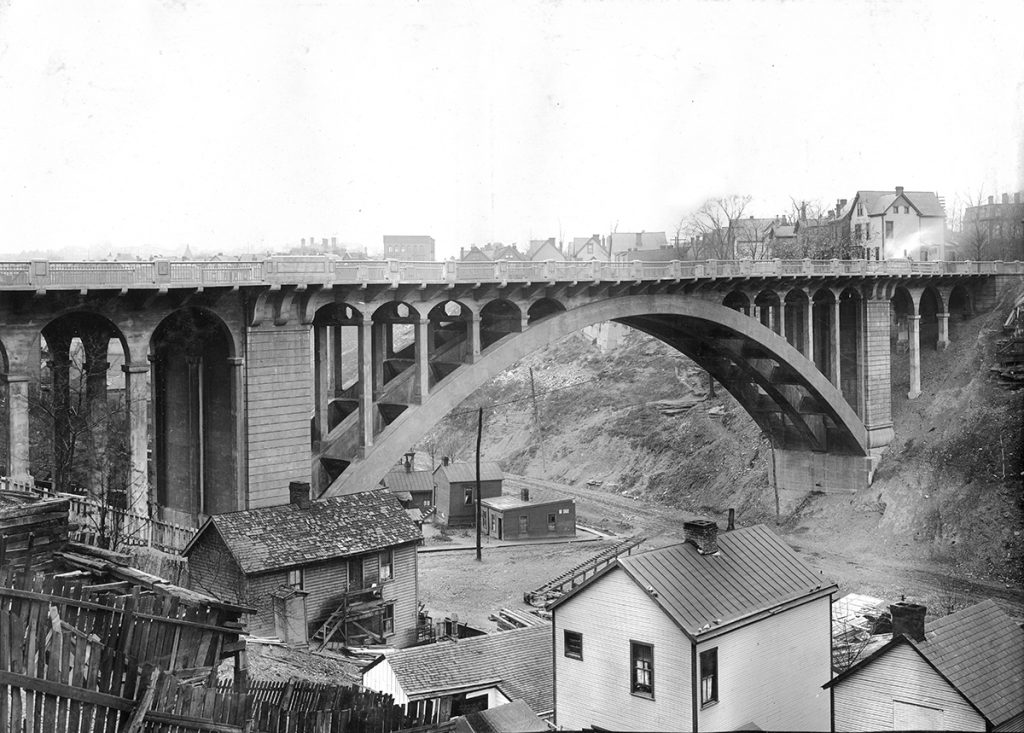

By November 1910 work was wrapping up on the ornate Meadow Street Bridge. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

The Walnut Lane Bridge was widely promoted in engineering literature of the day, and cities like Pittsburgh were quick to build similar structures. Locally, while utilitarian bridges continued to be built for typical ravine crossings, for a 40-year period beginning in 1910, concrete arch bridge designs were chosen for structures in parks, along boulevards and parkways, and at other prominent locations.

In the early 1900s, Pittsburgh was hoping to incorporate the valleys of the Negley Run watershed into Highland Park, where present-day Negley Run Boulevard and Washington Boulevard are located. This became the perfect location for the Pittsburgh Department of Public Works to experiment with concrete arch bridges. The city’s first bridge was built across present-day Negley Run Boulevard, extending Meadow Street from Larimer northward to the intersection of Stanton Avenue and Heberton Street in Highland Park.

Featuring decorative lampposts, paneled parapets, and other City Beautiful-era neoclassical details, the Meadow Street Bridge was built in 1910 with a 208-foot arch. From 1911 to 1912, the City replaced the Larimer Avenue streetcar viaduct over Washington Boulevard with a 300-foot arch, which according to its plaque, was the second longest arch bridge in the world upon completion in 1912 (presumably after New Zealand’s 1910 320-foot Grafton Bridge). A decorative plaque is located under the arch that was intended to be a monument along a park trail that was never built. The Larimer Avenue Bridge was determined to be historically significant in Pennsylvania’s first historic bridge survey in the 1980s and was awarded a Historic Landmark Plaque by Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation in 2019.

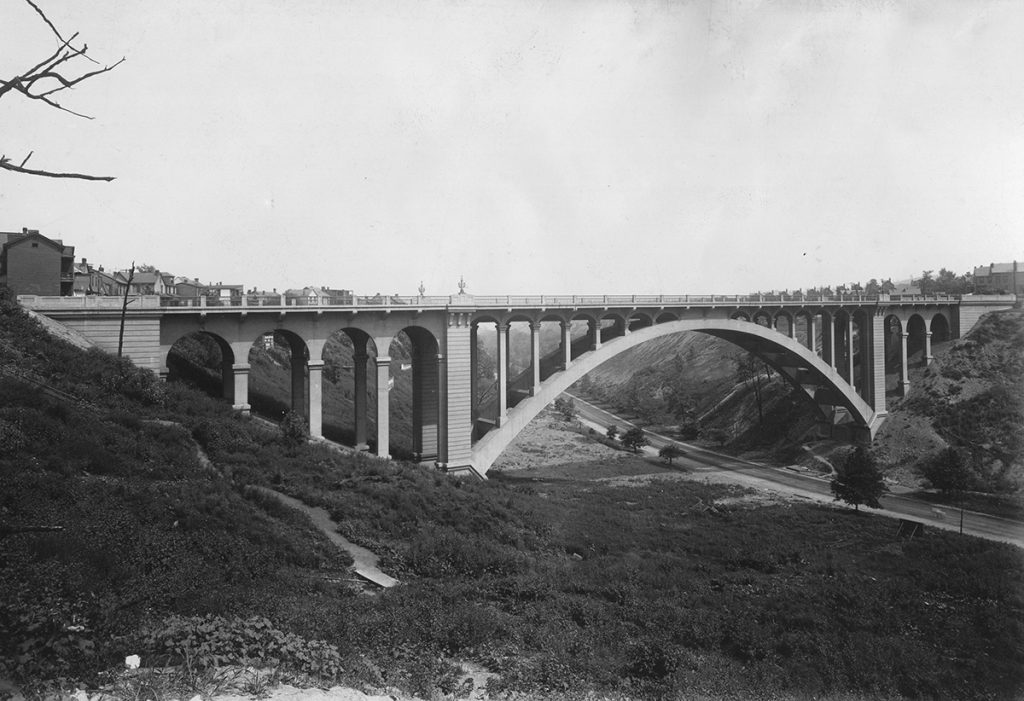

The Meadow Street Bridge as it looks today. During its 1962-63 rehabilitation, the entire structure above the arch ribs was replaced. Source: Todd Wilson.

With the initial success of these first two open spandrel reinforced concrete arch bridges, the City of Pittsburgh Public Works Department built several more within the next few years—on Baum Boulevard over Junction Hollow between Bloomfield and Oakland (1913), on Murray Avenue over Beechwood Boulevard between Squirrel Hill and Greenfield (1914), on Washington Boulevard over Heth’s Run in Highland Park (1914), on Beechwood Boulevard over the Four Mile Run Valley entering Schenley Park (1923), and on P.J. McArdle Roadway over Sycamore Street along the Mt. Washington hillside (1928). Stanley Roush served as the architect for these bridges.

The city also built a large three-span solid spandrel concrete arch on Baum Boulevard over the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1913, with the design chosen due to the long, shallow ravine that was more suitable for multiple smaller arches. While the other concrete arch bridges used wooden falsework for arch centering to hold the concrete forms, this bridge used Blawforms, self-supporting steel arch centering, that held the formwork in place without obstructing the railroad below. They were made by the company, which started in 1906 as the Blaw Collapsible Steel Centering Company, and merged in 1917 to become the Blaw-Knox Company. Many of these Blawforms forms manufactured in Blawnox were used to construct major concrete arch bridges all over the country.

Most of the city’s grand concrete bridges were built under Mayor Joseph Armstrong’s administration (1914-1918), first with neoclassical that transitioned to Art Deco detailing by Stanley Roush. When Armstrong became a County Commissioner in 1924, he led a massive road and building campaign that included the construction of record-breaking open spandrel concrete arch bridges.

This August 1913 photograph shows the newly-completed Larimer Avenue Bridge over the undeveloped part of the Negley Run ravine that the city unsuccessfully wanted to incorporate into Highland Park. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

These included the 320-foot California Avenue Bridge over Jacks Run (1925), the John P. Moore Bridge over Bausman Street in Knoxville (1928), and six Ohio River Boulevard bridges, the largest being the 420-foot arch over Jacks Run (1931). The cumulation of Allegheny County’s concrete arch building campaign was the five-span George Westinghouse Memorial Bridge over Turtle Creek with its record-breaking 460-foot central arch (1932). The bridge was awarded a PHLF Landmark Plaque in 1984. The last major reinforced concrete arch to be built in Pittsburgh was the 1952 Penn-Lincoln Parkway East Bridge over Nine Mile Run in Frick Park by the Pennsylvania Department of Highways.

While reinforced concrete bridges were once marketed as long-lasting “permanent” bridges, the expectation of concrete being a maintenance-free material proved to be unrealistic, often due to moisture penetrating through the concrete to the steel reinforcement. Concrete spalling was observed on some of the city’s bridges within 15 years of opening, and by the 1960s the Meadow Street Bridge had to be entirely rebuilt above the arch ribs.

The George Westinghouse Memorial Bridge, designed by architect Stanley Roush and engineers Vernon Covell and George S. Richardson opened in 1932. Its 460-foot central arch was the largest built at that time. Source: Todd Wilson.

In the 1970s and 1980s, just about every arch bridge was either rehabilitated or replaced, and continued deterioration led to the demolition of two City-built bridges in the 2010s. Among the City-built structures, only the Meadow Street arch ribs and the Larimer Avenue Bridge still survive. The newer County-built bridges fared better, with only the John P. Moore Bridge and the Ohio River Boulevard over Jacks Run Bridge having been demolished. However, many of the remaining bridges are showing signs of deterioration and have weight restrictions, and they face an uncertain future if unable to successfully be repaired or to keep up with modern traffic demands.

Despite being built in a relatively short 40-year period, the Pittsburgh area’s reinforced concrete arch bridges were monuments to what a developing city aspired to become—one with grand structures promoting civic ideals beautifying parks, parkways, and boulevards. Built with innovative techniques and spanning record-breaking distances, Pittsburgh’s reinforced concrete arch bridges set the standard for what concrete arch bridges could become, as larger record-breaking examples continue to be built to this day.

This January 1913 photograph shows the Baum Boulevard Bridge over the Pennsylvania Railroad valley under construction, with the steel Blawforms supporting the arches without falsework in the valley below. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

About the author: Todd Wilson, MBA, PE, is a transportation engineer in the Pittsburgh area who has traveled to all 50 states and over 25 countries photographing bridges. Having been awarded a Landmarks Scholarship to Carnegie Mellon University for his high school manuscript on Pittsburgh’s Bridges, he has since co-authored two books on the area’s bridges: Images of America: Pittsburgh’s Bridges (Arcadia, 2015) and Engineering Pittsburgh: A History of Roads, Rails, Canals, Bridges and More (History Press, 2018). He has won several awards, including being named one of Pittsburgh’s 40 under 40 and one of the American Society of Civil Engineers New Faces of Civil Engineering, and he serves as a Trustee of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

-

Architecture Feature: Hornbostel’s Work Inspires Artists

By David J. Vater

One measure of Henry Hornbostel’s architectural achievement which has so far eluded historical scholarship is the artistic response evoked by his distinctive designs. This is best seen if we consider the surprisingly large number of prominent American artists to include his structures among the subject matter of their artworks. These painterly depictions aim to be expressive of the character of our nation, the experience of place in American cities and their surrounding landscapes. In many cases the artists have chosen to represent these structures because they were among the most recognizable icons of their era.

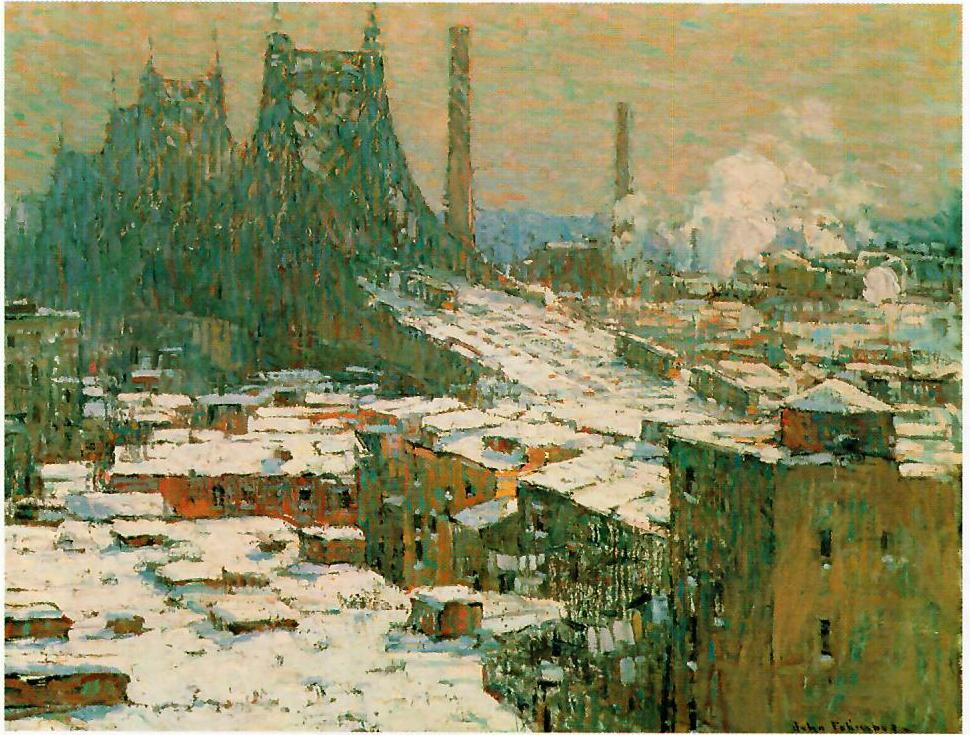

Notable artistic interest in Hornbostel’s designs began with his early work in New York city. The first paintings of the Queensboro Bridge which crossed the East River included impressionist scenes by Julian Alden Weir who painted the bridge as a nocturne, and Glenn O. Coleman whose loose brushwork depicted the shifting effects of sunlight and shadow. John Folinsbee painted the bridge as a snow scene. Leon Kroll made three separate views of the bridge. The American master Edward Hopper painted a spectacular moody view.

Other works depicting the Queensboro Bridge include ones by George W. Bellows, Ernest Lawson, Haley Lever, Joseph Delaney, Sebastin Cruset, and John Koch. Elsie Driggs rendered it in an exacting precisionist style, so did Blendon Reed Campbell. Hugh Conde Miller took a cubist approach showing a vibrating tangle of crisscrossed structural beams. Styvesant Van Veen’s painting of the Queensboro Bridge was shown in the 1929 Carnegie International.

The Manhattan Bridge was chosen as a subject for paintings by Esther Phillips, Raphael Soyer, Karl Zerbe, and Antonio Masi. John Marin made two water colors, and Edward Hopper painted four versions.

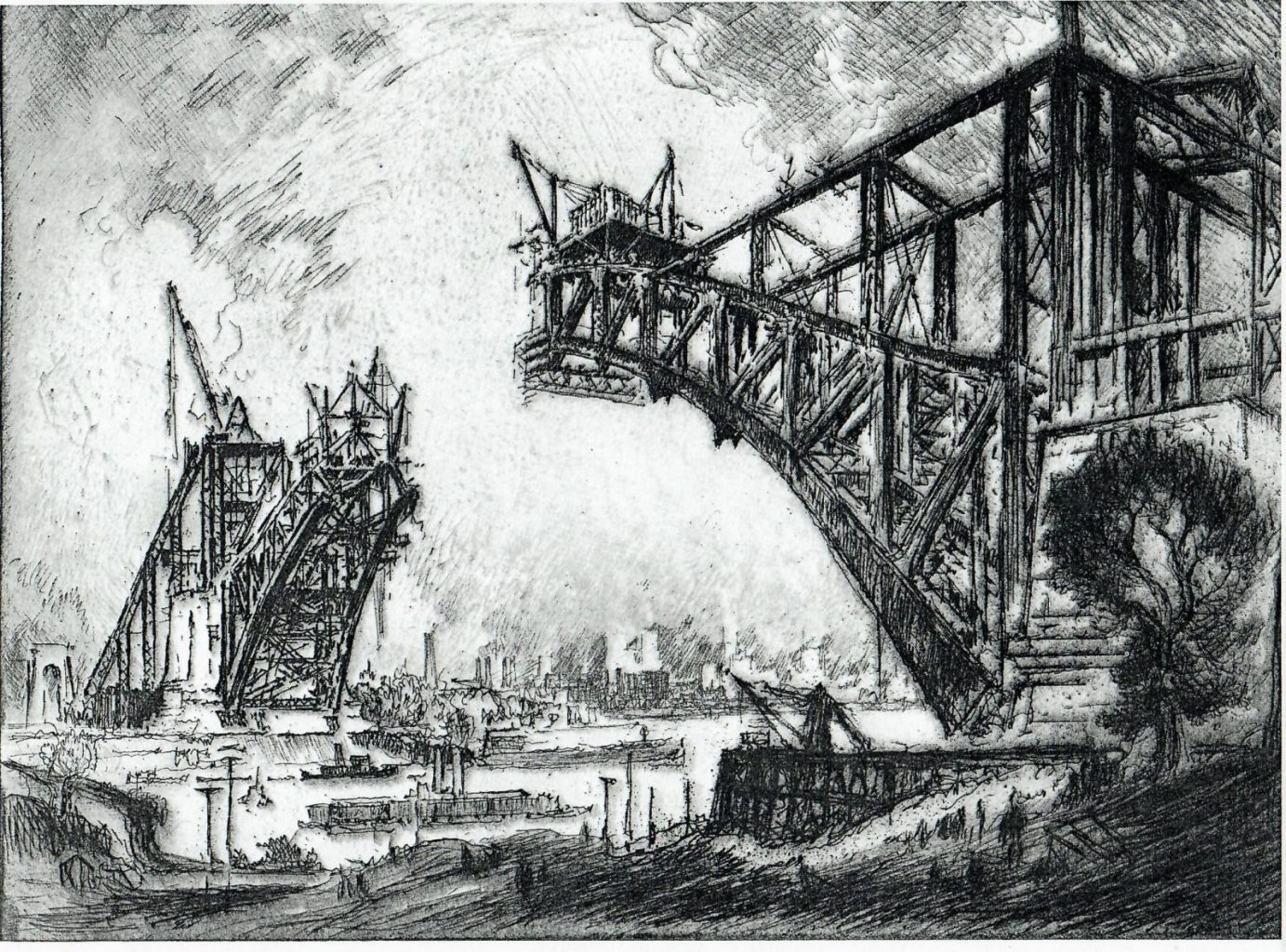

With its daring high arch and difficult site the Hell Gate Bridge attracted artistic attention even before it was finished. Joseph Pennell’s famous etching is one of two views he made, which show the uncompleted superstructure reaching up from opposite river banks. Surely it conveys a sense of the prowess of American engineering. Among the dozen artworks, which depict this bridge is the eight-foot long mural by James Monroe Hewlett in the lobby of the Fine Arts Building at Carnegie Mellon University.

For several Pittsburgh painters Hornbostel’s buildings were much more than just an aspect of daily life, they were seen as key city landmarks which resonated and conveyed local identity. The Grant Building was pictured in views of downtown by John Kane, Christian Walter, Louise Boyer, Raymond Simboli, Robert Qualters, and Michael Blaser.

Over a dozen Hornbostel buildings can be identified in landscapes and cityscapes by local artists. Rodef Shalom Congregation is included in paintings by Martin B. Leisser and John Kane. Webster Hall shows up in a view by Harry W. Scheuch. The delightful arcaded temple-like beacon of Hammerschlag Hall on the Carnegie Mellon campus is undoubtedly his most painted Pittsburgh building. It is featured in views by Martin B. Leisser, Edward B. Lee, Donald M. Shafer, Arthur Watson Sparks, Everett Warner, Joann Maier, Jill Watson, Douglas Cooper, and Robert Qualters. John Kane included it on three separate canvases.

Hornbostel was so fluent in the handling of the Beaux Arts style that we often fail to recognize the Americanness of his designs, which is found in their big welcoming gestures, their oversize proportions, the cosmopolitan equanimity of his grand public spaces, and his deliberate use of modern materials and innovative construction technologies; qualities which distinguish his work from the ordinary American eclecticism of his time and many of their European precedents.

To see all these artworks would require a cross country trip to many of our nation’s most important art collections. Images of Hornbostel’s work now hang on the walls of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, Hirshhorn Museum, Fogg Art Museum, Addison Gallery of American Art, Montclair Art Museum, and the Carnegie Museum of Art to name a few. They are also represented in the history museums of the New York Historical Society, Museum of the City of New York, and Heinz History Center. One particular canvas by William Glakens which depicts the misty but discernible arched profile of Hornbostel’s Hell Gate Bridge now hangs in the White House in Washington, DC.

Such sustained attention by important American artists re-positioned Hornbostel’s work as an intrinsic part of our national identity and the nation’s mass culture. It shows us how architectural design can contribute to the sense of place, take on significance and have a cultural impact on society far beyond its immediate functional use. The brushstrokes of these many paintings testify that the visual experience of architecture can be a rewarding community aesthetic experience which lingers long in our memory.

To see a working list of the many artworks, which depict Hornbostel’s structures click here.

David Vater is an architect, longtime member, and past Trustee of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

-

Architecture Feature: The McCann Cottage — Pittsburgh’s Version of a Craftsman’s Bungalow

By Bill Bates, FAIA, NOMA

When I was asked to write about my favorite building in Western Pennsylvania I was torn, given all of the iconic architecture in the region. I finally decided to highlight a building that I know better than any other, having lived in it for 41 years.

It’s a humble 1924 craftsman style bungalow located in the historic district of Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania. The McCann Cottage is named after its builder, Clyde McCann, who constructed approximately 48 of these one- and a-half story cottages in the South Hills. Unfortunately, the architect of this modest gem is

unknown.

unknown.The moment that I first saw the house I was struck by its solid form, which is reminiscent of H. H. Richardson’s Emmanuel Episcopal Church on Pittsburgh’s North Side. The fenestration’s graceful proportions provide a perfect lightness to the cottage’s otherwise heavy masonry and clay tile cloak. The stone exterior has a rustic elegance that celebrates the deft artistry of its masons, while the interior woodwork and cabinetry express a playful honesty that conveys a sense of restful comfort.

The basic model has two bedrooms on the first floor and two bedrooms on the second floor. Their exterior was typically constructed of local gray sandstone exterior walls with a hipped 10-on-12 pitch, clay tile roof. The builder produced several variations of the plan. There is an extended model that has two extra dormers on the side of the house and a porch that projects beyond the plane of the front facade. The basic model was also replicated in brick using the same footprint as the stone cottage. These houses are typically sited on corner lots allowing easy access to the integral tandem garage which opens on the side of the house.

One might expect the interiors to be dark but the house is very bright and airy thanks to its French casement windows that provide unimpeded views when opened and flood the cozy interior with light and abundant cross ventilation. Exterior views and access are further enhanced by the presence of 15 lite French doors opening onto the porch from the dining room and entry sunroom. Together all of these openings give the house a warm lantern-like street presence at night. The sunroom at the entry is wrapped with windows providing framed views in three directions.

The interior details feature a living room anchored by a large floor to ceiling ashlar cut stone fireplace, which echos the exterio

r. The living room is open to the dining room but the two spaces are given definition by the presence of two double-sided low glass-front cabinets that are capped off with truncated Tuscan columns and a sweeping wood archway.

r. The living room is open to the dining room but the two spaces are given definition by the presence of two double-sided low glass-front cabinets that are capped off with truncated Tuscan columns and a sweeping wood archway.The floor plan of both models of the cottage offers two bedrooms and a bath on the first floor that is ideal for aging in place. The extended model provides a larger kitchen and living room than the basic model but the circulation pattern is similar in both versions. The hipped roof extends over the integral front porch, which is also embraced by the stone facade affording the residents a shady summertime view of the neighborhood.

The half-story low gabled second floor was typically laid out for two bedrooms without a bath. However even the smaller basic model has adequate space to add a full bath. The walls consist of textured plaster that adds to the rustic craftsman charm of the structure.

The McCann Cottage has an unassuming charm that is immediately inviting and continues to reveal a depth of character over time.

Bill Bates, a Pittsburgh architect, has a long history of international development experience in corporate real estate and construction. A longtime member of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, he has served as the president of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) national, AIA Pennsylvania, and AIA Pittsburgh. He has also served as chair of our real estate development board and as chair of the boards of the Community Design Center and the Green Building Alliance.