Architecture Feature: Hornbostel’s Work Inspires Artists

By David J. Vater

One measure of Henry Hornbostel’s architectural achievement which has so far eluded historical scholarship is the artistic response evoked by his distinctive designs. This is best seen if we consider the surprisingly large number of prominent American artists to include his structures among the subject matter of their artworks. These painterly depictions aim to be expressive of the character of our nation, the experience of place in American cities and their surrounding landscapes. In many cases the artists have chosen to represent these structures because they were among the most recognizable icons of their era.

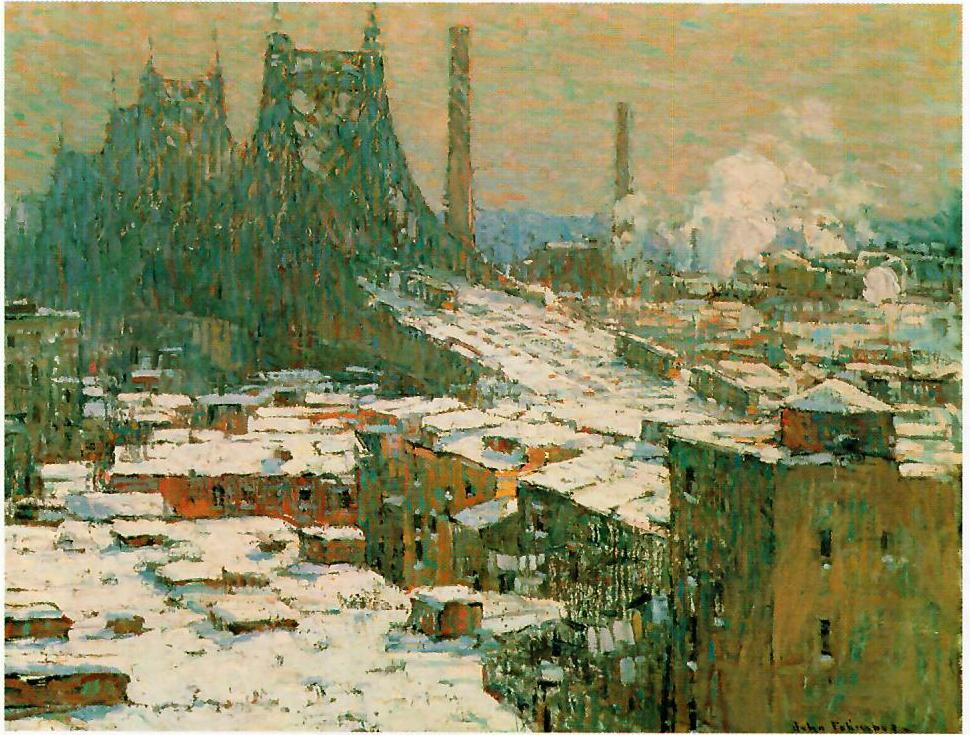

Notable artistic interest in Hornbostel’s designs began with his early work in New York city. The first paintings of the Queensboro Bridge which crossed the East River included impressionist scenes by Julian Alden Weir who painted the bridge as a nocturne, and Glenn O. Coleman whose loose brushwork depicted the shifting effects of sunlight and shadow. John Folinsbee painted the bridge as a snow scene. Leon Kroll made three separate views of the bridge. The American master Edward Hopper painted a spectacular moody view.

Other works depicting the Queensboro Bridge include ones by George W. Bellows, Ernest Lawson, Haley Lever, Joseph Delaney, Sebastin Cruset, and John Koch. Elsie Driggs rendered it in an exacting precisionist style, so did Blendon Reed Campbell. Hugh Conde Miller took a cubist approach showing a vibrating tangle of crisscrossed structural beams. Styvesant Van Veen’s painting of the Queensboro Bridge was shown in the 1929 Carnegie International.

The Manhattan Bridge was chosen as a subject for paintings by Esther Phillips, Raphael Soyer, Karl Zerbe, and Antonio Masi. John Marin made two water colors, and Edward Hopper painted four versions.

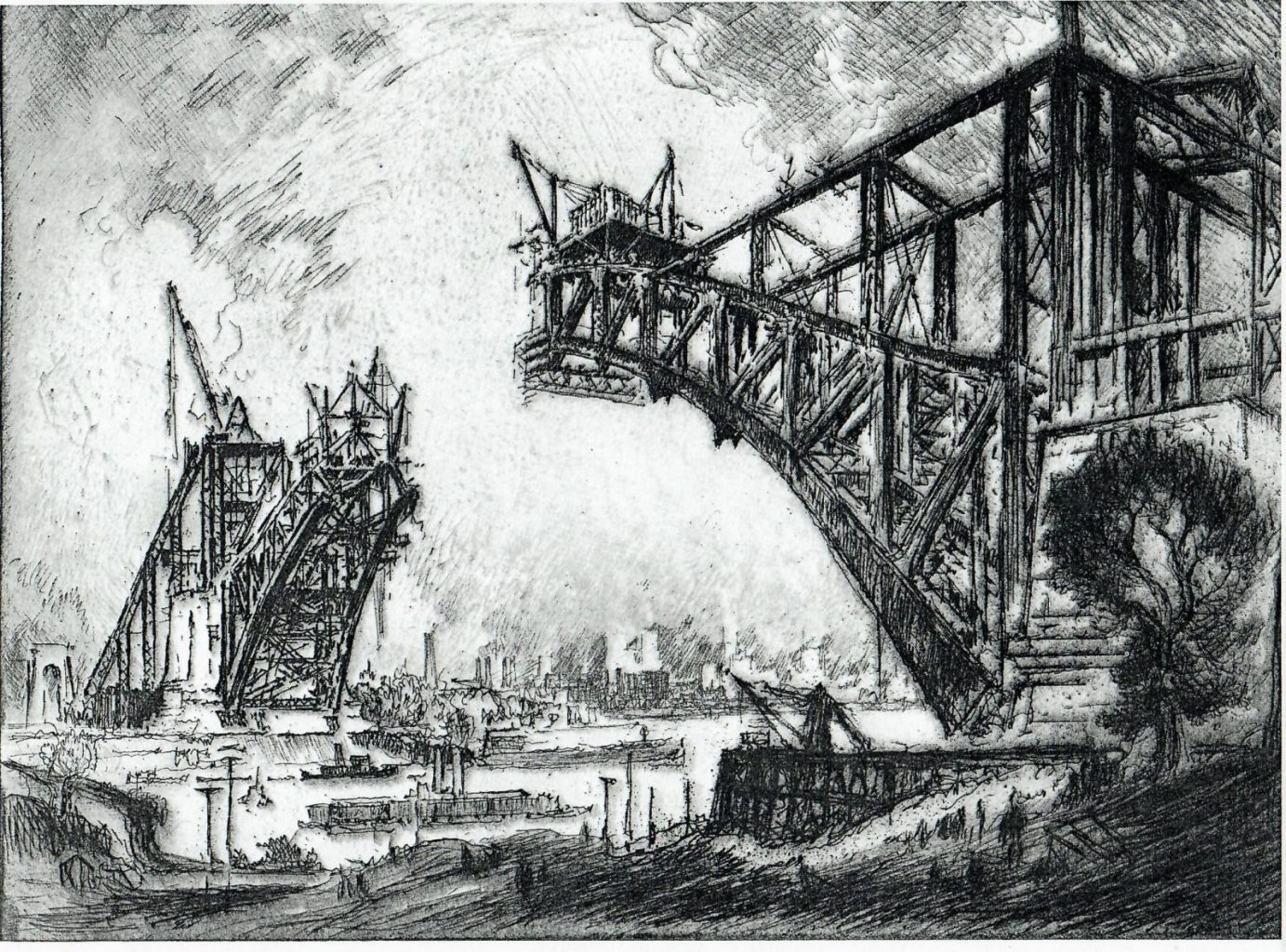

With its daring high arch and difficult site the Hell Gate Bridge attracted artistic attention even before it was finished. Joseph Pennell’s famous etching is one of two views he made, which show the uncompleted superstructure reaching up from opposite river banks. Surely it conveys a sense of the prowess of American engineering. Among the dozen artworks, which depict this bridge is the eight-foot long mural by James Monroe Hewlett in the lobby of the Fine Arts Building at Carnegie Mellon University.

For several Pittsburgh painters Hornbostel’s buildings were much more than just an aspect of daily life, they were seen as key city landmarks which resonated and conveyed local identity. The Grant Building was pictured in views of downtown by John Kane, Christian Walter, Louise Boyer, Raymond Simboli, Robert Qualters, and Michael Blaser.

Over a dozen Hornbostel buildings can be identified in landscapes and cityscapes by local artists. Rodef Shalom Congregation is included in paintings by Martin B. Leisser and John Kane. Webster Hall shows up in a view by Harry W. Scheuch. The delightful arcaded temple-like beacon of Hammerschlag Hall on the Carnegie Mellon campus is undoubtedly his most painted Pittsburgh building. It is featured in views by Martin B. Leisser, Edward B. Lee, Donald M. Shafer, Arthur Watson Sparks, Everett Warner, Joann Maier, Jill Watson, Douglas Cooper, and Robert Qualters. John Kane included it on three separate canvases.

Hornbostel was so fluent in the handling of the Beaux Arts style that we often fail to recognize the Americanness of his designs, which is found in their big welcoming gestures, their oversize proportions, the cosmopolitan equanimity of his grand public spaces, and his deliberate use of modern materials and innovative construction technologies; qualities which distinguish his work from the ordinary American eclecticism of his time and many of their European precedents.

To see all these artworks would require a cross country trip to many of our nation’s most important art collections. Images of Hornbostel’s work now hang on the walls of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, Hirshhorn Museum, Fogg Art Museum, Addison Gallery of American Art, Montclair Art Museum, and the Carnegie Museum of Art to name a few. They are also represented in the history museums of the New York Historical Society, Museum of the City of New York, and Heinz History Center. One particular canvas by William Glakens which depicts the misty but discernible arched profile of Hornbostel’s Hell Gate Bridge now hangs in the White House in Washington, DC.

Such sustained attention by important American artists re-positioned Hornbostel’s work as an intrinsic part of our national identity and the nation’s mass culture. It shows us how architectural design can contribute to the sense of place, take on significance and have a cultural impact on society far beyond its immediate functional use. The brushstrokes of these many paintings testify that the visual experience of architecture can be a rewarding community aesthetic experience which lingers long in our memory.

To see a working list of the many artworks, which depict Hornbostel’s structures click here.

David Vater is an architect, longtime member, and past Trustee of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.