Category Archive: PHLF News

-

Concrete Bridges of the Steel City

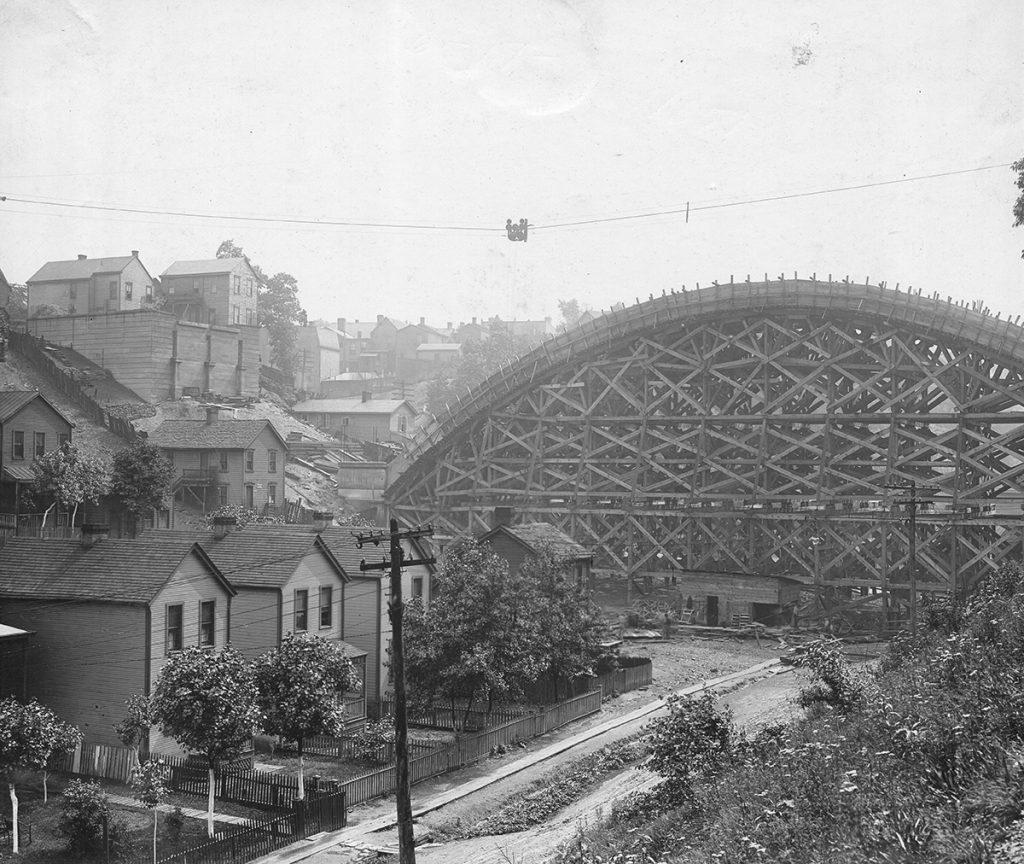

Construction of the Meadow Street Bridge in June 1910, with wooden falsework towering over the valley and the concrete arch starting to take shape. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

By Todd Wilson

While Pittsburgh may be known as “The Steel City,” many beautiful and significant concrete bridges were built here. Concrete is a rock-like mixture of fine and coarse aggregates (sand, gravel, stone) pasted together with a binder made up of Portland cement and water. Replacing natural cement, Portland cement (named for its resemblance to Portland stone from the Isle of Portland in England) is made from limestone, clay, and gypsum.

Portland cement was patented in 1824 and first manufactured in America in Lehigh County in 1871. As with stone structures, concrete is strong when compressed, but it is much weaker when being pulled apart in tension. A few concrete arch bridges started to be built in America in the 1870s, though it was not until steel reinforcement began to be added to concrete to withstand tensile forces starting around 1890, that the true potential of concrete structures could start to be realized.

The first large-scale concrete arch bridge was Luxembourg’s 1904 Pont Adolphe, with open spandrel walls and a 278-foot main span. Impressed, Philadelphia built a similar bridge in 1908, the Walnut Lane Bridge in Fairmount Park, having a 233-foot main span. Adorned with City Beautiful embellishments, it showcased how concrete could be used as an architectural material especially appropriate for parklike settings. The soaring arch avoided the need for intermediate supports infringing into the valley below, and using concrete instead of stone allowed for a more economical bridge with a longer span.

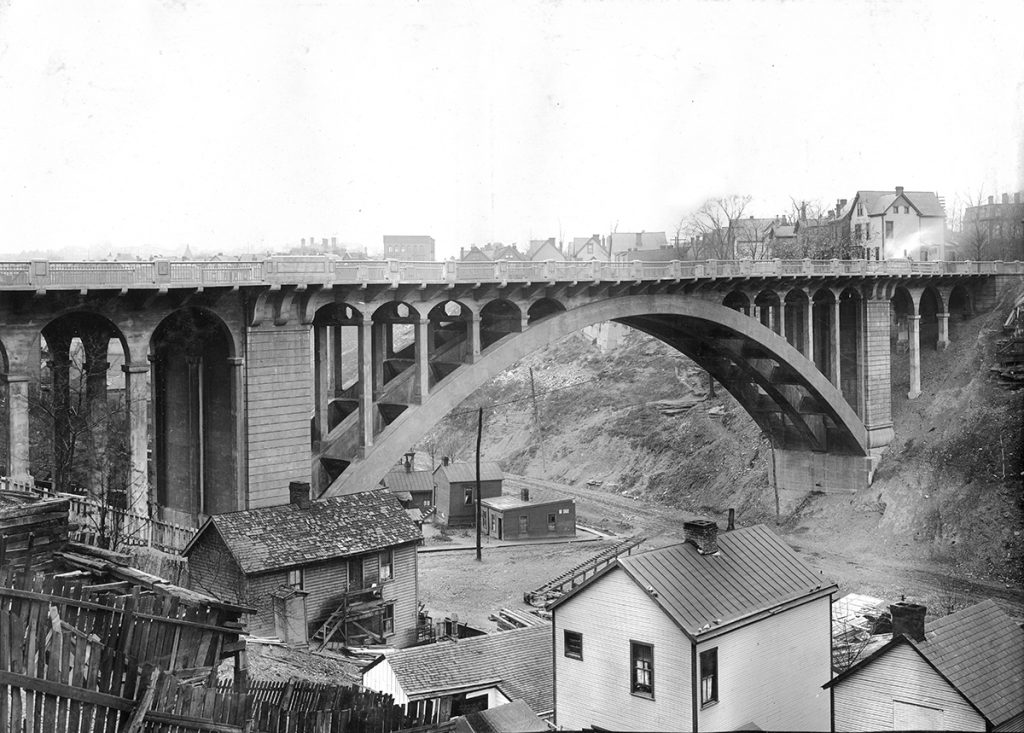

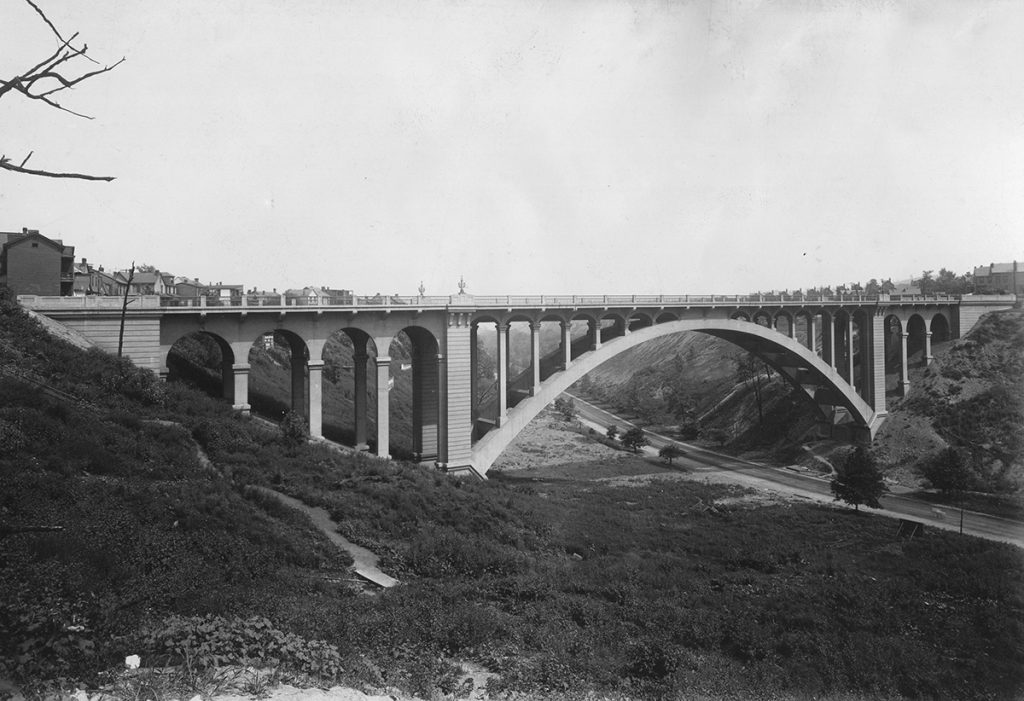

By November 1910 work was wrapping up on the ornate Meadow Street Bridge. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

The Walnut Lane Bridge was widely promoted in engineering literature of the day, and cities like Pittsburgh were quick to build similar structures. Locally, while utilitarian bridges continued to be built for typical ravine crossings, for a 40-year period beginning in 1910, concrete arch bridge designs were chosen for structures in parks, along boulevards and parkways, and at other prominent locations.

In the early 1900s, Pittsburgh was hoping to incorporate the valleys of the Negley Run watershed into Highland Park, where present-day Negley Run Boulevard and Washington Boulevard are located. This became the perfect location for the Pittsburgh Department of Public Works to experiment with concrete arch bridges. The city’s first bridge was built across present-day Negley Run Boulevard, extending Meadow Street from Larimer northward to the intersection of Stanton Avenue and Heberton Street in Highland Park.

Featuring decorative lampposts, paneled parapets, and other City Beautiful-era neoclassical details, the Meadow Street Bridge was built in 1910 with a 208-foot arch. From 1911 to 1912, the City replaced the Larimer Avenue streetcar viaduct over Washington Boulevard with a 300-foot arch, which according to its plaque, was the second longest arch bridge in the world upon completion in 1912 (presumably after New Zealand’s 1910 320-foot Grafton Bridge). A decorative plaque is located under the arch that was intended to be a monument along a park trail that was never built. The Larimer Avenue Bridge was determined to be historically significant in Pennsylvania’s first historic bridge survey in the 1980s and was awarded a Historic Landmark Plaque by Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation in 2019.

The Meadow Street Bridge as it looks today. During its 1962-63 rehabilitation, the entire structure above the arch ribs was replaced. Source: Todd Wilson.

With the initial success of these first two open spandrel reinforced concrete arch bridges, the City of Pittsburgh Public Works Department built several more within the next few years—on Baum Boulevard over Junction Hollow between Bloomfield and Oakland (1913), on Murray Avenue over Beechwood Boulevard between Squirrel Hill and Greenfield (1914), on Washington Boulevard over Heth’s Run in Highland Park (1914), on Beechwood Boulevard over the Four Mile Run Valley entering Schenley Park (1923), and on P.J. McArdle Roadway over Sycamore Street along the Mt. Washington hillside (1928). Stanley Roush served as the architect for these bridges.

The city also built a large three-span solid spandrel concrete arch on Baum Boulevard over the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1913, with the design chosen due to the long, shallow ravine that was more suitable for multiple smaller arches. While the other concrete arch bridges used wooden falsework for arch centering to hold the concrete forms, this bridge used Blawforms, self-supporting steel arch centering, that held the formwork in place without obstructing the railroad below. They were made by the company, which started in 1906 as the Blaw Collapsible Steel Centering Company, and merged in 1917 to become the Blaw-Knox Company. Many of these Blawforms forms manufactured in Blawnox were used to construct major concrete arch bridges all over the country.

Most of the city’s grand concrete bridges were built under Mayor Joseph Armstrong’s administration (1914-1918), first with neoclassical that transitioned to Art Deco detailing by Stanley Roush. When Armstrong became a County Commissioner in 1924, he led a massive road and building campaign that included the construction of record-breaking open spandrel concrete arch bridges.

This August 1913 photograph shows the newly-completed Larimer Avenue Bridge over the undeveloped part of the Negley Run ravine that the city unsuccessfully wanted to incorporate into Highland Park. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

These included the 320-foot California Avenue Bridge over Jacks Run (1925), the John P. Moore Bridge over Bausman Street in Knoxville (1928), and six Ohio River Boulevard bridges, the largest being the 420-foot arch over Jacks Run (1931). The cumulation of Allegheny County’s concrete arch building campaign was the five-span George Westinghouse Memorial Bridge over Turtle Creek with its record-breaking 460-foot central arch (1932). The bridge was awarded a PHLF Landmark Plaque in 1984. The last major reinforced concrete arch to be built in Pittsburgh was the 1952 Penn-Lincoln Parkway East Bridge over Nine Mile Run in Frick Park by the Pennsylvania Department of Highways.

While reinforced concrete bridges were once marketed as long-lasting “permanent” bridges, the expectation of concrete being a maintenance-free material proved to be unrealistic, often due to moisture penetrating through the concrete to the steel reinforcement. Concrete spalling was observed on some of the city’s bridges within 15 years of opening, and by the 1960s the Meadow Street Bridge had to be entirely rebuilt above the arch ribs.

The George Westinghouse Memorial Bridge, designed by architect Stanley Roush and engineers Vernon Covell and George S. Richardson opened in 1932. Its 460-foot central arch was the largest built at that time. Source: Todd Wilson.

In the 1970s and 1980s, just about every arch bridge was either rehabilitated or replaced, and continued deterioration led to the demolition of two City-built bridges in the 2010s. Among the City-built structures, only the Meadow Street arch ribs and the Larimer Avenue Bridge still survive. The newer County-built bridges fared better, with only the John P. Moore Bridge and the Ohio River Boulevard over Jacks Run Bridge having been demolished. However, many of the remaining bridges are showing signs of deterioration and have weight restrictions, and they face an uncertain future if unable to successfully be repaired or to keep up with modern traffic demands.

Despite being built in a relatively short 40-year period, the Pittsburgh area’s reinforced concrete arch bridges were monuments to what a developing city aspired to become—one with grand structures promoting civic ideals beautifying parks, parkways, and boulevards. Built with innovative techniques and spanning record-breaking distances, Pittsburgh’s reinforced concrete arch bridges set the standard for what concrete arch bridges could become, as larger record-breaking examples continue to be built to this day.

This January 1913 photograph shows the Baum Boulevard Bridge over the Pennsylvania Railroad valley under construction, with the steel Blawforms supporting the arches without falsework in the valley below. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

About the author: Todd Wilson, MBA, PE, is a transportation engineer in the Pittsburgh area who has traveled to all 50 states and over 25 countries photographing bridges. Having been awarded a Landmarks Scholarship to Carnegie Mellon University for his high school manuscript on Pittsburgh’s Bridges, he has since co-authored two books on the area’s bridges: Images of America: Pittsburgh’s Bridges (Arcadia, 2015) and Engineering Pittsburgh: A History of Roads, Rails, Canals, Bridges and More (History Press, 2018). He has won several awards, including being named one of Pittsburgh’s 40 under 40 and one of the American Society of Civil Engineers New Faces of Civil Engineering, and he serves as a Trustee of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

-

Architecture Feature: Hornbostel’s Work Inspires Artists

By David J. Vater

One measure of Henry Hornbostel’s architectural achievement which has so far eluded historical scholarship is the artistic response evoked by his distinctive designs. This is best seen if we consider the surprisingly large number of prominent American artists to include his structures among the subject matter of their artworks. These painterly depictions aim to be expressive of the character of our nation, the experience of place in American cities and their surrounding landscapes. In many cases the artists have chosen to represent these structures because they were among the most recognizable icons of their era.

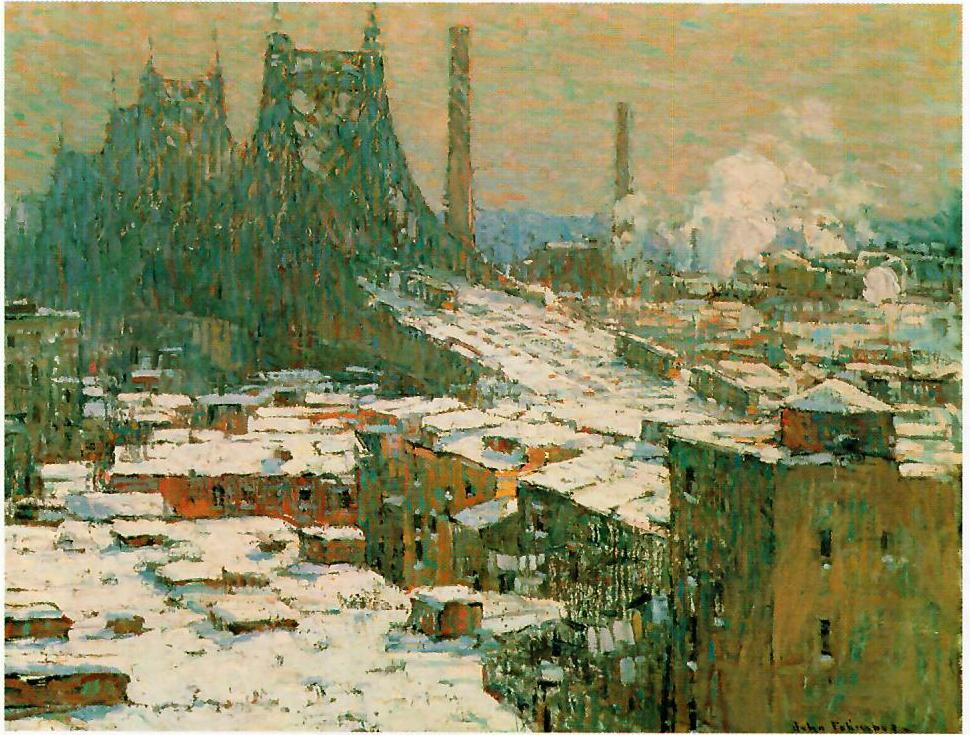

Notable artistic interest in Hornbostel’s designs began with his early work in New York city. The first paintings of the Queensboro Bridge which crossed the East River included impressionist scenes by Julian Alden Weir who painted the bridge as a nocturne, and Glenn O. Coleman whose loose brushwork depicted the shifting effects of sunlight and shadow. John Folinsbee painted the bridge as a snow scene. Leon Kroll made three separate views of the bridge. The American master Edward Hopper painted a spectacular moody view.

Other works depicting the Queensboro Bridge include ones by George W. Bellows, Ernest Lawson, Haley Lever, Joseph Delaney, Sebastin Cruset, and John Koch. Elsie Driggs rendered it in an exacting precisionist style, so did Blendon Reed Campbell. Hugh Conde Miller took a cubist approach showing a vibrating tangle of crisscrossed structural beams. Styvesant Van Veen’s painting of the Queensboro Bridge was shown in the 1929 Carnegie International.

The Manhattan Bridge was chosen as a subject for paintings by Esther Phillips, Raphael Soyer, Karl Zerbe, and Antonio Masi. John Marin made two water colors, and Edward Hopper painted four versions.

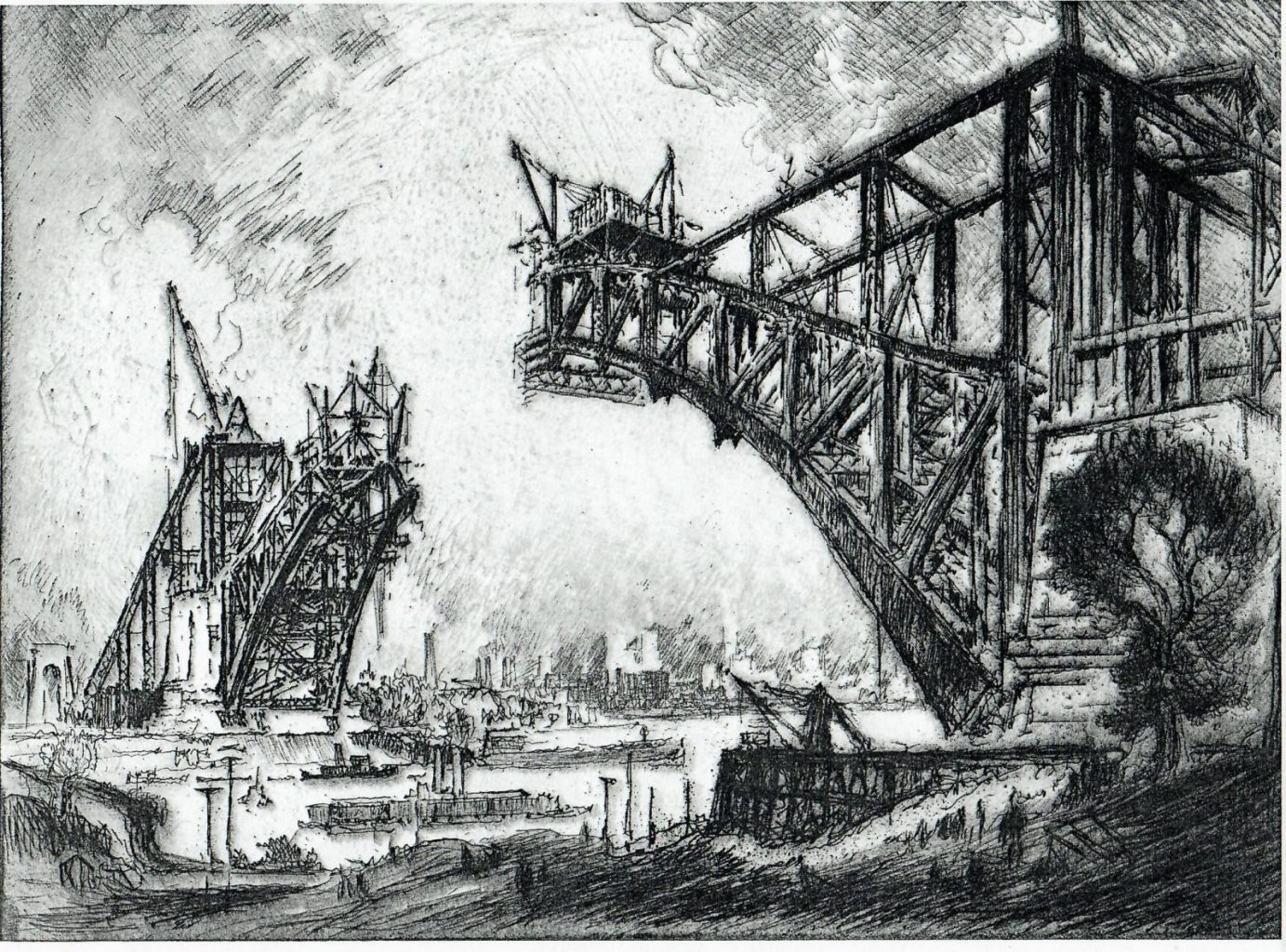

With its daring high arch and difficult site the Hell Gate Bridge attracted artistic attention even before it was finished. Joseph Pennell’s famous etching is one of two views he made, which show the uncompleted superstructure reaching up from opposite river banks. Surely it conveys a sense of the prowess of American engineering. Among the dozen artworks, which depict this bridge is the eight-foot long mural by James Monroe Hewlett in the lobby of the Fine Arts Building at Carnegie Mellon University.

For several Pittsburgh painters Hornbostel’s buildings were much more than just an aspect of daily life, they were seen as key city landmarks which resonated and conveyed local identity. The Grant Building was pictured in views of downtown by John Kane, Christian Walter, Louise Boyer, Raymond Simboli, Robert Qualters, and Michael Blaser.

Over a dozen Hornbostel buildings can be identified in landscapes and cityscapes by local artists. Rodef Shalom Congregation is included in paintings by Martin B. Leisser and John Kane. Webster Hall shows up in a view by Harry W. Scheuch. The delightful arcaded temple-like beacon of Hammerschlag Hall on the Carnegie Mellon campus is undoubtedly his most painted Pittsburgh building. It is featured in views by Martin B. Leisser, Edward B. Lee, Donald M. Shafer, Arthur Watson Sparks, Everett Warner, Joann Maier, Jill Watson, Douglas Cooper, and Robert Qualters. John Kane included it on three separate canvases.

Hornbostel was so fluent in the handling of the Beaux Arts style that we often fail to recognize the Americanness of his designs, which is found in their big welcoming gestures, their oversize proportions, the cosmopolitan equanimity of his grand public spaces, and his deliberate use of modern materials and innovative construction technologies; qualities which distinguish his work from the ordinary American eclecticism of his time and many of their European precedents.

To see all these artworks would require a cross country trip to many of our nation’s most important art collections. Images of Hornbostel’s work now hang on the walls of the Whitney Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, Hirshhorn Museum, Fogg Art Museum, Addison Gallery of American Art, Montclair Art Museum, and the Carnegie Museum of Art to name a few. They are also represented in the history museums of the New York Historical Society, Museum of the City of New York, and Heinz History Center. One particular canvas by William Glakens which depicts the misty but discernible arched profile of Hornbostel’s Hell Gate Bridge now hangs in the White House in Washington, DC.

Such sustained attention by important American artists re-positioned Hornbostel’s work as an intrinsic part of our national identity and the nation’s mass culture. It shows us how architectural design can contribute to the sense of place, take on significance and have a cultural impact on society far beyond its immediate functional use. The brushstrokes of these many paintings testify that the visual experience of architecture can be a rewarding community aesthetic experience which lingers long in our memory.

To see a working list of the many artworks, which depict Hornbostel’s structures click here.

David Vater is an architect, longtime member, and past Trustee of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

-

Architecture Feature: The McCann Cottage — Pittsburgh’s Version of a Craftsman’s Bungalow

By Bill Bates, FAIA, NOMA

When I was asked to write about my favorite building in Western Pennsylvania I was torn, given all of the iconic architecture in the region. I finally decided to highlight a building that I know better than any other, having lived in it for 41 years.

It’s a humble 1924 craftsman style bungalow located in the historic district of Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania. The McCann Cottage is named after its builder, Clyde McCann, who constructed approximately 48 of these one- and a-half story cottages in the South Hills. Unfortunately, the architect of this modest gem is

unknown.

unknown.The moment that I first saw the house I was struck by its solid form, which is reminiscent of H. H. Richardson’s Emmanuel Episcopal Church on Pittsburgh’s North Side. The fenestration’s graceful proportions provide a perfect lightness to the cottage’s otherwise heavy masonry and clay tile cloak. The stone exterior has a rustic elegance that celebrates the deft artistry of its masons, while the interior woodwork and cabinetry express a playful honesty that conveys a sense of restful comfort.

The basic model has two bedrooms on the first floor and two bedrooms on the second floor. Their exterior was typically constructed of local gray sandstone exterior walls with a hipped 10-on-12 pitch, clay tile roof. The builder produced several variations of the plan. There is an extended model that has two extra dormers on the side of the house and a porch that projects beyond the plane of the front facade. The basic model was also replicated in brick using the same footprint as the stone cottage. These houses are typically sited on corner lots allowing easy access to the integral tandem garage which opens on the side of the house.

One might expect the interiors to be dark but the house is very bright and airy thanks to its French casement windows that provide unimpeded views when opened and flood the cozy interior with light and abundant cross ventilation. Exterior views and access are further enhanced by the presence of 15 lite French doors opening onto the porch from the dining room and entry sunroom. Together all of these openings give the house a warm lantern-like street presence at night. The sunroom at the entry is wrapped with windows providing framed views in three directions.

The interior details feature a living room anchored by a large floor to ceiling ashlar cut stone fireplace, which echos the exterio

r. The living room is open to the dining room but the two spaces are given definition by the presence of two double-sided low glass-front cabinets that are capped off with truncated Tuscan columns and a sweeping wood archway.

r. The living room is open to the dining room but the two spaces are given definition by the presence of two double-sided low glass-front cabinets that are capped off with truncated Tuscan columns and a sweeping wood archway.The floor plan of both models of the cottage offers two bedrooms and a bath on the first floor that is ideal for aging in place. The extended model provides a larger kitchen and living room than the basic model but the circulation pattern is similar in both versions. The hipped roof extends over the integral front porch, which is also embraced by the stone facade affording the residents a shady summertime view of the neighborhood.

The half-story low gabled second floor was typically laid out for two bedrooms without a bath. However even the smaller basic model has adequate space to add a full bath. The walls consist of textured plaster that adds to the rustic craftsman charm of the structure.

The McCann Cottage has an unassuming charm that is immediately inviting and continues to reveal a depth of character over time.

Bill Bates, a Pittsburgh architect, has a long history of international development experience in corporate real estate and construction. A longtime member of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, he has served as the president of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) national, AIA Pennsylvania, and AIA Pittsburgh. He has also served as chair of our real estate development board and as chair of the boards of the Community Design Center and the Green Building Alliance.

-

Preservation Anchors Our Communities

By Michael Sriprasert

It is with honor and humility that I assume the presidency of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, succeeding Arthur Ziegler after his extraordinary 56-year tenure leading our organization.

It is with honor and humility that I assume the presidency of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, succeeding Arthur Ziegler after his extraordinary 56-year tenure leading our organization.Under his leadership, PHLF has become one of the leading preservation organizations in the country, with the broadest array of preservation programming ranging from high impact education initiatives in our schools and for the public, to neighborhood and urban real estate revitalization programs that have improved the quality of life for all.

Arthur has created a tremendous platform from which to build upon for generations to come.

I have been extremely fortunate to have been immersed in the culture of PHLF over the past 14 years, working as partners with Arthur over the past nine years as president of two of our subsidiaries. Through our work, I have learned firsthand how preservation impacts our lives, how it provides hope and pride in our communities, and how it fosters economic development opportunities in our neighborhoods and in our Downtown.

I have also learned how preservation can be an anchor in our communities during times of uncertainty. I believe, like our friend Anthony Wood, founder and chair of the New York Preservation Archive Project, that, “in times of great upheaval, solace can come from those things and places that provide stability and continuity.”

The role of our work in the communities we serve has never been more important. As we move forward, we will maintain our grassroots approach, listening to community needs and advocating for our historic buildings in city neighborhoods, Downtown, Main Streets, and in towns and historic rural communities of our region.

In our rapidly changing world, we will continue to evolve how we work, integrating more technology and data into our programs and initiatives. I am excited about the tremendous opportunity that lies ahead, and to continuing our work with our various Boards of Trustees, our staff, and all the individuals and organizations that support us.

Michael Sriprasert

Vice-president -

Michael Sriprasert Named President of PHLF

I am very pleased to announce that Michael Sriprasert, our vice-president, who also heads two of our subsidiaries—Landmarks Community Capital and Landmarks Development Corporations— will become president of this organization on August 10. I will then assume a new role as President Emeritus.

This is the culmination of a process and discussion about the future of our organization that our Boards of Trustees started in 2011. The leadership of our organization felt then—and we still do— that we had an excellent and enterprising staff member in Michael, who not only understood preservation real estate, but also how it influences and impacts our ability to achieve great results in historic preservation as a tool of community development.

Since then, Michael has led our lending subsidiary, transforming it into a Community Development Financial Institution, which has raised significant funds to help organizations, individuals, and businesses, finance extensive historic restoration and preservation projects in the region.

Michael later took on the leadership of the Landmarks Development Corporation, our for-profit real estate development subsidiary, which is the vehicle through which we undertake significant historic preservation and adaptive reuse initiatives everywhere we are engaged.

He has gained indelible experience on almost all fronts of our organization’s work in neighborhoods, Main Street communities, cities, and towns in our region. Among Michael’s early and biggest accomplishments was his ability to advocate for and secure funding for preservation projects through utilization of historic rehabilitation and low-income housing tax credits.

To that end, Michael led our comprehensive preservation and community development initiative in Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, where we have created 67 units of affordable and subsidized housing in beautifully restored buildings for people of low- and moderate- income. Our work in Wilkinsburg showcases what we believe should be the challenge of a modern historic preservation organization— to help improve the quality of lives of people through preservation.

Indeed, we not only restored historic buildings in Wilkinsburg, but acquired and cleaned up blighted vacant lots, created community gardens, established an educational center, provided loans to small businesses and non-profits, and grants to historic churches, expanded social service outreach for our tenants in subsidized housing, and created two National Register Historic Districts, to help incentivize others to redevelop historic buildings. This represents more than $25 million invested in the community, establishing a beachhead for renewal.

Michael has led our efforts in lending, preservation real estate development, and advocacy in Downtown Pittsburgh, in the historic North Side, Hill District, South Side, and Hilltop neighborhoods in the city.

A native of Maryland, Michael grew up near Washington D.C., and came to Pittsburgh in 2002 to pursue a Coro Fellowship in Public Affairs. He is a graduate of Kenyon College and holds two Masters degrees— one in Public Policy and Management from the Heinz College and a Master of Business Administration from the Tepper School of Business—from Carnegie Mellon University. He joined the staff of our organization in 2006.

We are ready and have long prepared for this transition. We have hired new and younger staff members over the years as some of our most dedicated long-term staffers have retired or partially retired, but we retain a lot of our institutional memory. It is therefore appropriate that we look to the future with a young leader who has been immersed in the culture and principles that guide our organization.

I am especially proud that we have had a diverse organization not just in ethnic composition but in various life experiences. This has been reflected in our staff, our board members, and community partners, since the creation of this organization in 1964.

With Michael at the helm, we will continue to reflect leadership with the integration of diverse voices in our organization. I will remain active, and I will be available to Michael and our various Boards of Trustees as an advisor. I will have certain duties to perform, but Michael will be our leader.

Our Trustees, our staff members, and the wider community have enabled us to build one of the finest preservation organizations in the United States. I want to thank you all for your support of our organization and for me through the years.

Arthur Ziegler

President -

Landmarks Scholarship Reception Welcomes New Recipients

More than 50 attendees welcomed the newest Landmarks Scholarship and honorable mention recipients during PHLF’s 22nd annual scholarship reception, which was held by videoconference on July 9.

This online gathering of previous recipients, new winners, their families, committee members, and PHLF staff, congratulated the current cohort of nineteen high-achieving, community-minded young people on receiving their awards.

“We have developed many customs over the years within the Landmarks Scholarship Program; one that we cherish is our celebration. […] This year, for the first time ever, we are not gathering together in person. Like much in our lives, we are resorting to an online gathering,” said David Brashear, chair of the committee and founder of PHLF’s Scholarship program.

“We will miss our opportunities to talk one on one – and to get to know each other – but hopefully, next year, many of you will come back to attend our 2021 Celebration,” he added.

Thanks to the generosity of committee members and to the continuing support of the Brashear Family Fund, the McSwigan Family Foundation Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation, and the Landmarks Scholarship Fund, the committee was able to award 3 new scholarships, each with a maximum value of $6,000 payable over a four-year period. The committee also awarded 16 honorable mention awards, a one-time award of $250. This year had the biggest number of honorable mention recipients the committee has ever awarded in any one year.

“Thank you for the [virtual] celebration!” said Emily Petrina, who received a scholarship from PHLF in 1999. “It was great to see everyone on the PHLF team, as well as all of the past and present award winners. It was more heartwarming than I expected to hear from all of these people with whom I have a shared history. Get-togethers like this seem to mean more these days in such an uncertain world.”

Sam Zlotnikov, a 2020 Scholarship recipient added, “Thank you so very much for today’s meeting. Although it would have been splendid to meet everyone in person, it was great to hear from previous winners!”

Since the program’s inception in 1999, PHLF has awarded 79 scholarships and 30 honorable mentions, thereby connecting with 109 young people who care deeply about the Pittsburgh region. This is a fantastic achievement that brings new life, commitment, and energy to our organization.

“We welcome contributions from members and friends in this, our 22nd anniversary year, to support our very successful program that has a profound and lasting impact on the students it has served and on PHLF,” said Mr. Brashear.

Please click here to contribute and direct your gift to “Scholarship Programs.”

Thank you!

-

Free Neighborhood Book for PHLF Family Members––Summer Fun!

If you are a PHLF member with elementary-school-age children or grandchildren, you may request a free copy of Neighborhood Stories, Including Mine. The 42-page book contains stories about Squirrel Hill and Brookline by fourth-grade students from Pittsburgh Colfax, as well as tips and worksheets that any child can use with an adult this summer to explore his or her neighborhood. Most importantly, there is room in the book for a child to add his or her neighborhood story, drawing, or photograph––thereby completing Neighborhood Stories, Including Mine.

Please contact Frank Stroker (412-471-5808, ext. 525) if you would like him to mail you one or more books. Frank will mail books to everyone who requests them during the week of July 20. Neighborhood Stories, Including Mine helps young people notice and appreciate the strengths of their neighborhoods and think about ways to improve their neighborhoods. When a family member completes a neighborhood story, please photograph or scan it and email it to Sarah Greenwald, PHLF’s co-director of education, who will save it in our Neighborhood Stories Archive.

“We hope to receive at least one story for every Pittsburgh neighborhood, along with stories about neighborhoods throughout Allegheny County and Western Pennsylvania,” said Louise Sturgess, education advisor at PHLF. Five fourth-grade students from Pittsburgh Roosevelt, who participated in PHLF’s “Building Pride/Building Character” Educational Improvement Tax Credit Program, mailed their stories to PHLF at the end of the school year.

Mt. Oliver, A Borough Completely Surrounded by Pittsburgh, by Avery

Mt. Oliver is a small borough that is about .34 square miles in total and was founded in 1769 by Captain John Ormsby. It sits completely surrounded by 6 neighborhoods in the City of Pittsburgh. In 1927, the City of Pittsburgh tried to force Mt. Oliver Borough to become a part of the City. After many legal battles, it was declared that Pittsburgh had no rights to Mt. Oliver, and it has since remained its own borough. Because of its small size, Mt. Oliver does pay taxes to the City of Pittsburgh to use their school system, and that’s why I am here writing my story today!

On a fall day here in Mt. Oliver, you will see the usual fallen leaves and people bustling about; and you will hear the loud noises of cars and buses. Mt. Oliver has a nice mix of houses, apartment buildings, and businesses. The business district of Mt. Oliver boasts a borough building, a police department, a volunteer fire station, post office, florist, bakery, barbershop, and many other stores. One notable landmark you won’t miss while driving or walking through Mt. Oliver is the big clock tower that sits at the intersection of Brownsville Road and Hayes Avenue.

While taking a walk to the business district, we stopped at the barbershop so my older brother could get a haircut. Since we were there, I thought I’d ask the barber a couple of questions about the business and the neighborhood.

Question: “Do you like being a barber?”

Answer: “Love it. I love seeing all of my regular clients and sometimes new faces.”

Question: “Do you like the location of your barber shop?”

Answer: “Very much. I like to watch all of the people pass by while out shopping.

In conclusion, living in Mt. Oliver doesn’t seem any different than living in the City since no matter which direction I go in, there is a City neighborhood surrounding me. I do, however, like being tucked away in my own little borough.

Carrick, by Nyla

I live in Carrick. My neighborhood is very calm. When I step outside, I see the colorful leaves falling off the trees. I interviewed my Mom and she said that the neighbors participate in holidays. For example, people pass out lots of candy and dress up on Halloween. A lot of people are friendly, and traveling to Downtown is easy. She enjoys her job as a case worker which allows her to help people get food and other resources within the community.

Is your neighborhood like mine? Or is it different?

My Beautiful Neighborhood, by Mi’Kiyah

Hello, my name is Mi’Kiyah. I am going to tell you about my community and neighborhood.

To me, community means a whole bunch of people, plants, and streets.

This is what I treasure and care about most. I want to protect plants because they give us oxygen. There is a beautiful garden and there are beautiful plants in my neighborhood, and I often get flowers for my Mom and family.

Thank you for listening to my story.

How I Got to Go to Anthony’s Pizza for Softball, by Kaylee

When I played softball in Carrick, we had to make a banner and walk in a parade. We put softballs on the banner with our names on them. The winning team got to eat at Anthony’s Pizza. We were very excited when we heard we won.

When I got to Anthony’s Pizza, my team was just playing tag outside. I was sitting at the table with my friends. We were just talking until the pizza arrived. When we got the pizza, we were happy to eat the pizza. Then we got our photograph taken at Anthony’s, and it was hung on the wall.

When we were done eating, we just hung out for awhile outside, and then we all left and went home.

The end.

About My Community, by Nya

Hi, my name is Nya and I live in the neighborhood of Mt. Oliver. I’m going to share with you about my community.

To me, my community means to share common habits and interests with others around me.

This is what I treasure about my community. I care about my family, population, and litter. I want to protect animals, people, and my family.

To help care for my community I can help on Earth Day. I can use bottles that can be used again, and I can support others by saying nice words: “Awesome,” “You did great,” and “Nice job.”

To help take care of myself, I can get more sleep, study, and practice my clarinet more often. That’s what I need to do more.

Thanks for listening.

-

Eden-Hall Gifted Sixth-Graders Propose New Uses for an Old Building

Fifty-one gifted sixth-graders at Eden Hall Upper Elementary School in the Pine-Richland School District learned much about resilience and perseverance in completing their work for PHLF’s Fifth Annual Sustainable Design Challenge this spring. The Design Challenge is a collaboration of PHLF and Chatham University’s Eden Hall campus, where the curriculum and daily life revolve around environmental sustainability. It was supported this year by the McSwigan Family Foundation Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation.

The subject of this year’s Design Challenge was the Morledge House Garage, a wood-frame, Dutch gambrel-roofed building of about 550 square feet located on the Eden Hall Campus, not far from the elementary school. After a tour of the Eden Hall campus and an opportunity to examine and document the Garage last October, the students were given their task: to convert it into a place for the community to gather and learn about the Campus’s mission and activities. Working in 12 teams, the students were encouraged to “think big,” pursue ideas that excite and inspire them, and transform those ideas into building uses that are meaningful to them. Their final designs were to be captured in architectural models they would present to a panel of jurors for review and critique at the beginning of May.

Projects were well underway when COVID-19 slammed the brakes on life as we know it. Having left their drawings and other working materials behind when the school closed on March 20, the students were forced to reconstruct their projects from memory. The teams continued to work on-line from home; without their models and drawings, however, they had to convey their ideas through slide presentations, using only words and allusive pictures.

Despite the difficult circumstances, the students produced a wonderfully rich stew of imaginative ideas for transforming the Morledge House Garage. Among the new functions they envisioned:

- a place for re-selling used clothing and books, and an organic community garden;

- a center for teaching marketable skills like sewing, auto repair, and cooking, together with an art studio and garden;

- a survival camp where hands-on activities teach participants how sustainability connects to nature;

- a “Healthy Hearts Community Center,” with library, yoga studio, maker space, and bike rental and repair shop;

- a building with indoor and outdoor zones for a variety of activities designed to help people with disabilities; and

- a center for the study of butterflies, color, and air quality, with a café selling seasonal fruits.

The students’ extensive research was evident in the numerous sustainable materials and other elements their projects incorporated. Cork flooring, aluminum interior walls, solar exterior paint, roof gardens, bicycle-generated electricity, book cases constructed from dead trees found on the site, a chair re-purposed from a grocery cart, and natural illumination were among the strategies the students employed to maximize their projects’ sustainability. And as several teams pointed out, the most sustainable aspect of their work was re-using the historic building.

“I’m always amazed at how quickly students in our design programs ramp up to an understanding of architectural ideas. We kind of throw them in the deep end and say, ‘OK, kids, here’s your assignment. Have at it!’ What they produced was thoughtful and sophisticated,” said Tracy Myers, co-director of education. The jury, comprised of architects, specialists in sustainability, and PHLF staff, agreed, noting that they had previously been unaware of some of the materials the students proposed.

Jennifer Kopach and Joanna Sovek, teachers at Eden Hall Upper Elementary who have been involved with the Design Challenge since its first year at the school, said, “We are incredibly proud of our 6th-grade students. We talk about resiliency all the time. These students showed resiliency and perseverance. Their positivity and success provided closure and a sense of accomplishment. We are so happy their hard work paid off and excited for them as they begin their next adventure.”

A lesson for all of us as we continue to adapt to uncertainty and changing circumstances. Well done, kids!