Leo Thomas (1876-1950) for George Boos (1859-1937), Munich, Germany

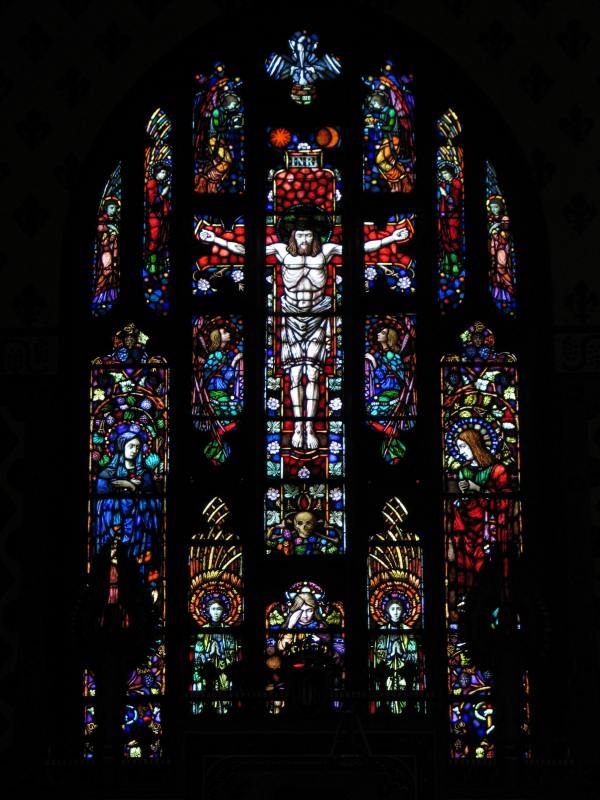

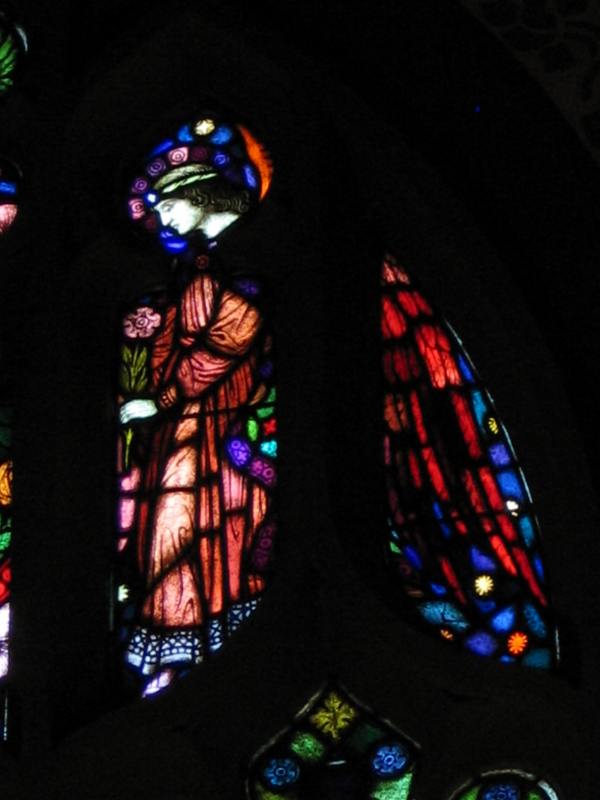

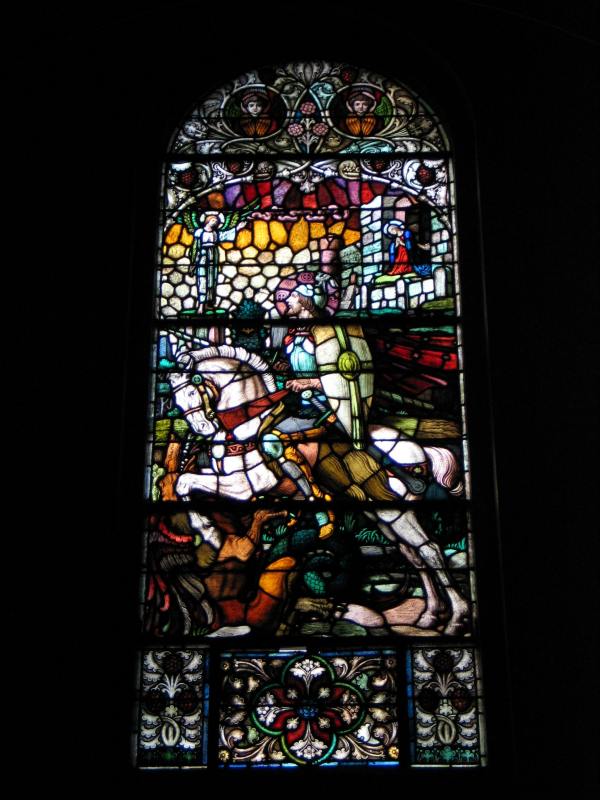

Leo Thomas (1876-1950) for George Boos (1859-1937), Munich, Germany: Chancel window and detail of transept angel, 1910-11, St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, Butler, Pa., John T. Comes, architect; “Tu Es Petrus” and St. George, 1911-12, St. George’s Roman Catholic Church; Herman J. Lang, architect

Photographs and text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

“Munich glass”—stained glass made in Munich, Germany (then the kingdom of Bavaria)—originated during the reign of Ludwig I of Bavaria (1786-1868) who sought to turn his capital into an unrivaled center of German art and culture. The leading Munich glass firms were Mayer & Co., founded by Josef Gabriel Mayer and later led by his son Franz, and F. X. Zettler (the firms later merged; Mayer & Co. is still in business). Jean Farnsworth tells us that Mayer & Co. was founded in 1847 to make ecclesiastical furnishings. Josef Gabriel’s son-in-law, Franz Xavier Zettler, organized the firm’s glass workshop in the 1860s, then founded his own glass firm in 1870. Both companies quickly won royal and papal endorsements. Mayer & Co. and Zettler opened sales offices in the U.S.A. in 1888 and c. 1902 respectively. Their earliest documented glass in the Pittsburgh Diocese dates to 1890.

The artistic language of Munich glass owed much to the revival of religious painting, especially fresco painting, in Germany early in the 19th-century. Kathleen Curran notes: “The fresco revival had its origins in Rome in 1812, when the young Peter Cornelius sought out Friederich Overbeck and joined the Brotherhood of St. Luke. Cornelius’s special contribution to that movement was the renewal of fresco painting in the tradition of the Italian Renaissance masters, especially Masaccio, Raphael, and Michelangelo.” Ludwig I sent German art and German artists to the United States. Curran observes that St. Vincent’s Benedictine Abbey in Latrobe, Pa, forty miles west of Pittsburgh, received some 300 paintings from King Ludwig, and Munich-trained artists like William Lamprecht taught fresco painting at St. Vincent; he and pupils like Bonaventure Ostendarp and Raphael Pfisterer painted religious art in Roman Catholic churches throughout the Mid-Atlantic and Mid-Western states during the second half of the 19th century.

Although Munich windows were made of traditional hand-blown antique glass, both Munich windows and American opalescent windows typically eschew the flatness and emphatic leading of medieval windows in favor of an idealized naturalism and spatial realism. Wealthy Protestants might prefer opalescent windows, which were complicated and expensive to make, but Munich glass windows could be imported as art, i.e., glass “paintings” and—exempt from a high tariff on imported “raw” glass—cost less than opalescent windows and windows made in America using imported glass. Although often derided by English glass artists as too pictorial, and viewed as an economic threat by American glass firms, the broad aesthetic appeal, economic advantage, and papal approval made Munich glass windows the overwhelming choice among Roman Catholics in the United States.

George Boos of Munich began his career at Mayer & Co., then established his own firm c. 1880. Shortly thereafter, his 7-year-old nephew Leo Thomas, born in London, moved to Munich. Leo studied at the Munich Arts & Crafts School and the Museum of Fine Arts. He traveled to Italy, Tunis, and, in 1906, England. Jean Farnsworth observes: “Leo sometimes developed designs for windows based on cartoons in the Victoria & Albert Museum, including those of Edward Burne-Jones.” She further cites a 1912 German stained glass publication that “refers to George Boos’s ‘modern’ aesthetic, characterized by many small pieces of glass in a dense network of leads, suggesting the studio’s interpretation of the Neo-Gothic.” While Boos glass in Philadelphia is “more conservative, and in keeping with the techniques of the Munich pictorial style: relatively large pieces of glass and minimal emphasis on the leads” she also observes that “much of [the firm’s] work . . . is particularly notable for its emotionally charged, non-idealized depictions of the sacred stories [and] lacks the Raphaelesque sweetness so typical of the Munich style.”

Between 1910 and 1912 Leo designed over 60 stained glass windows made in Germany by the Boos firm for two new Roman Catholic churches in the Diocese of Pittsburgh: St. Paul’s, Butler, dedicated September 10, 1911, and St. George’s, Pittsburgh, dedicated July 7, 1912.

St. Paul’s, Butler, was designed by John T. Comes (1873-1922), one of Pittsburgh’s leading Roman Catholic church architects. It was the almost certainly Comes, who described St. Paul’s windows as:

the realization of old ideals worked out with modern means…. The windows were made by the firm of George Boos in Munich, and to Leo Thomas a nephew of Mr. Boos is due all credit for their beauty of color and design. Messrs. Boos and Thomas have been comparatively unknown in this country heretofore, but it is safe to say that work like that which we are considering will soon win for them an international reputation.

The chancel window and an angel from the tracery of the transept windows at St. Paul’s, and two of the twelve nave windows at St. George’s (now St. John Vianney Parish) are illustrated. The windows exhibit a stylized two dimensionality, with backgrounds and ornamental sections composed of “many small pieces of glass in a dense network of leads.” In these windows, the flat, heavily leaded neo-medieval meets the abstract to create strikingly “modern” images, akin to the work of contemporary Secessionist designers in Austria and Hungary.

Comes described St. Paul’s as English Gothic and designed all the furnishings. The chancel was painted by the Christian Art Guild of Pittsburgh. The metalware was made by the St. Dunstan’s Guild of the Society of Arts & Crafts, Boston, and the Birmingham [England] Guild of Handicraft.

St. George’s Church is located in Pittsburgh’s Allentown neighborhood—The Pittsburgh Catholic called the building “an adaptation of the German Romanesque style to suit modern needs”—was designed by Herman J. Lang (born c. 1885), a native of Hesse, Germany, who came to Pittsburgh in 1901 to join his brother, Edmund (1875-1955), in the architectural firm of Edmund B. Lang & Brother. The brothers designed Roman Catholic churches in Pittsburgh together through 1910 and separately thereafter. Edmund moved to Los Angeles after 1918; Herman Lang maintained his office in suburban Carrick where he lived with his wife and three sons, and where his best-known church building, St. Basil, is located.

Sources: John T. Comes, et al., A Notable Work of Christian Art: St. Paul’s Church Butler Pa., Dedicated Sept. 10 MCMXI. “Solemn Dedication, Grand Diocesan Event: St. George’s Church Allentown,” The Pittsburgh Catholic, 6 June 1912. John T. Comes, Catholic Art and Architecture (Pittsburgh 1920). Jean Farnsworth, et al., Stained Glass in Catholic Philadelphia (Philadelphia 2002), 135, 152-153, 180, 196, 354-355, 381, 395, 427-428. Kathleen Curran, The Romanesque Revival (University Park, Pa., 2003): 75, 84-91. Elgin Vaassen, Bilder Auf Glass (Munich/Berlin 1997), 257-258, 350. Thanks to Jean Farnsworth, Gail Campbell, Diocesan Archivist Burris Esplen, Dr. Elgin van Treeck-Vaassen, and Leo Thomas’ granddaughter, Barbara Deeken.

Illustrations

- St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, Butler, Pa.

- Chancel window

- Tracery angel, transept window

- St. George’s Roman Catholic Church, Pittsburgh, Pa

- “Tu Es Petrus”

- St. George