Latest News

-

Visit Photo Antiquities on the North Side to See “The Abraham Lincoln Photographic Exhibition”

- Open: Mondays, Wednesdays through Saturdays.

- Hours: 10 a.m. – 4 p.m.

- Ground floor access ADA compliant

- For information: 412-231-7881; bruce817@yahoo.com

PHLF docents and staff toured the Photo Antiquities Museum of Photographic History at 531 East Ohio Street on Pittsburgh’s North Side on April 3. They were fascinated to see how the museum, that began 21 years ago with one display case, has grown to fill five rooms in two historic buildings.

The Lincoln exhibit, opening on May 1, is the largest display of vintage original photographs ever shown under one roof. The exhibit will be on display for one year and will have historical Lincoln photos and artifacts rotating in and out.

Visitors to the exhibit will see:

- The last check Abraham Lincoln wrote before attending Ford’s Theater

- A large oil painting by A. F. King of Lincoln, based on a Mathew Brady photograph

- A quarter-plate Daguerreotype copy of Alexander Hesler’s 1860 portrait

- Vintage photographs by N. H. Shepherd, W. J. Thompson, M. B. Brady, A. Hesler, C. S. German, A. Gardner, and H. F. Warren

- Documents and a portrait by Mathew B. Brady, signed by Lincoln

- A bronze bust of Lincoln in 1860, by Volk, mounted onto a pedestal base

- A plaster Life Mask by Clark Mills

- A copy of a Philadelphia Derringer

- A replica of the Ford’s Theater chair

- An original copy of the Dedication Gettysburg National Cemetery book, c.1864, which contains the first printing of the Gettysburg Address

- Various period prints of Lincoln

- A wax life-like portrait head of Lincoln, by Ivo Zini, c.1980

-

Architecture Feature: Grosvenor Atterbury’s Pittsburgh Buildings

A postcard of the former Federal Street Bridge, which preceded the present-day Sixth Street/Roberto Clemente Bridge, with a view of the four Pittsburgh buildings by Grosvenor Atterbury. Only the Fulton Building (just left of the bridge), now the Renaissance Pittsburgh Hotel, remains.

By Albert M. Tannler

Grosvenor Atterbury (1869-1956) designed buildings of unusual diversity and character.[1] We will explore his career and the four buildings he created for Pittsburgh between 1904 and 1908.

Atterbury was born in Detroit, Michigan. His father was a lawyer, and Atterbury spent summers on Long Island, New York, where his family had a house. He attended Yale University, graduating in 1891. After six months traveling in Europe and Egypt, he enrolled in Columbia University where he studied architecture for two years. During this period he worked in the office of McKim, Mead & White (Stanford White was a family friend) and studied painting during the summer with William Merritt Chase. In 1894 he began a two-year course of study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. When he returned to New York in 1896, he established his own architectural practice, and moved into the family house on Long Island. He began his career designing townhouses, country houses, and cultural and social facilities such as the Parrish Art Museum and the Southhampton Club near his home.[2]

Atterbury’s residential architecture primarily reflected asymmetrical Shingle Style influences and often found inspiration in the picturesque buildings of Britain and Central and Southern Europe.[3]

Atterbury’s Pittsburgh buildings were erected rapidly—in part simultaneously—within a four-year-period, and stood shoulder-to-shoulder along the Allegheny River.[4]

Bessemer and Fulton Buildings

The Bessemer Building was erected 1904-05 at 100 Sixth Street. It was a popular landmark—many postcards survive and photographs were published of both the exterior and the interior.[5] At 13 stories, the stone and brick clad, steel-frame building was a typical office “skyscraper” of the time. Rough-cut Stony Creek granite covered the first-three floors of the facade. The stone base, decorative “quoins” (bands of masonry) around each corner, and the bracketed, wide-eaved, shallow hipped roof pavilions recall Italian Renaissance palaces. The lobby was marble-clad, with polychromatic geometric tile trim and steel grillwork ornamented with an innovative fusion of Renaissance pattern and exposed rivets and bolts. Atterbury displayed two drawings of the Bessemer Building in the 1905 Pittsburgh Architectural Club (PAC) exhibition.

The building was demolished in 1964; a parking garage now occupies the site. The Bessemer and the Fulton Building, erected across Sixth Street, were clearly intended to complement each other. As PHLF’s architectural historian James Van Trump observed in 1967: “It is a great pity that the Bessemer Building was demolished because the two structures together formed a monumental entrance, a kind of triumphal arch at the river entrance to Sixth Street.”[6]

By October 1905 the Fulton Building was rapidly rising at 107 Sixth Street. Completed in early 1906, the Fulton is the larger building. “A steel frame building with an envelope of brick and granite,” Van Trump wrote, “it has … a skylighted interior court that serves as a lobby. This great court with its monumental staircase and galleries is unusually spacious … and gave rise to a legend that the structure had originally been constructed as a hotel.”[7] Light enters the lobby through the great art glass skylight lit by a central light court, facing the river and dramatically exposed to view, and even more dramatically framed by a seven-story arch.

Van Trump refers to a letter Atterbury wrote in 1909 denying that the Fulton had been designed as a hotel (both the recipient and the whereabouts of the letter are currently unknown).[8] Ironically, if prophetically, the Fulton Building now houses the Renaissance Pittsburgh Hotel.

Manufacturer’s Building and the Natatorium

The Manufacturer’s Building was located at 530 Duquesne Way (now Fort Duquesne Boulevard).[9] Construction began September 14, 1906, and the 16-story building was completed in 1907. Elevation drawings were displayed at the 1907 PAC exhibition and photographs and postcards exist, but less is known about this building than any of the others. It was the tallest member of the ensemble. Although it shared their granite base, the Manufacturer’s Building had a ten-story shaft of great simplicity topped by a three-story penthouse—an architectural Easter bonnet displaying classical forms—gables with balustrades, fan and circular windows, symmetrical rough-cut stone trim. The Manufacturer’s Building was not an office building, like the Bessemer or Fulton buildings, but a loft building, offering tenants high ceilings and unobstructed floor space.[10] The building was demolished in 1956 and a parking garage now occupies the site.

The Pittsburgh or Phipps Natatorium, a bathhouse and swimming pool, was soon erected at 540 Duquesne Way, behind the Manufacturer’s Building, and could be entered through it. The building was designed and built 1907-08; Atterbury displayed three views of the swimming pool at the 1907 exhibition. In 1980, Van Trump wrote about Pittsburgh bathhouses in Pittsburgher Magazine, observing:

Even more stylish—truly a bathing establishment of Roman Splendor—was the Natatorium, a structure of almost imperial dimensions. The four-story structure was located on Duquesne Way near the Sixth Street Bridge. This was a commercial rather than a charitable venture. Anyone who had 25 cents could get a tub bath, but the place was chiefly famous as possessing the first great swimming pool in Pittsburgh.[11]

The swimming pool was clad in Guastavino tile, a light-weight, fire-proof acoustical tile used in churches, railroad stations, public buildings, and occasionally private homes. Four detailed drawings for the pool have been preserved in the Guastavino Company Archives at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.[12] The Natatorium was demolished in 1935 to reduce property taxes and the site remained vacant for some years.

Atterbury after Pittsburgh

Atterbury last displayed his work in Pittsburgh at the 1910 PAC exhibition—houses he had designed years before at Bayberry Point, Long Island. He continued to design country estates on Long Island; he redecorated major rooms in New York City Hall, and he designed the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1924-25). He designed hospitals and medical facilities, including the Yale University Medical Library, and educational buildings and clubhouses.

He also continued to design worker housing in New York City, and experimented with prefabricated reinforced concrete to produce standardized, low-cost housing. He became an urban planner/designer, first and most notably at Forest Hills Gardens in Queens (1909-13), where he and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. created a 140-acre planned community 15 minutes from Manhattan by train. Atterbury designed Indian Hill Village for the Norton Company in Worchester, Mass. (1915-16), as well as worker housing in Cincinnati, Mocanaqua, Pa. (Luzerne County), and Erwin and Kingsport, Tennessee.[13]

By all accounts, Atterbury had a successful career. His idealistic commitment to affordable housing may have been uncommon, but his exploration of innovative technologies while creatively re-imagining traditional forms was typical of peers such as Burnham, Hornbostel, and Post, as recent studies have shown.[14] Still, as biographer David Dwyer notes: “It was as a town planner with a special concern for housing the poor and for hospitals that he wished to be known. Architects with such interests rarely become famous.”[15]

[1]The first critical study of Atterbury was published in 2008: Peter Pennover, and Anne Walker, The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008).

[2] Donald Dwyer, “Grosvenor Atterbury, 1869-1956.” Long Island Country Houses and Their Architects, 1860-1940, ed. by Robert B. MacKay, Anthony Baker, and Carol A. Taynor (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 49-57. Also “Biographical Sketch” (May 22, 1953), Grosvenor Atterbury papers, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Carl K. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

[3] For illustrations of his work, in addition to Long Island Country Houses cited above and Pittsburgh Architectural Club exhibition catalogs cited below see American Architect and Building News 94 (August 26, 1908) and (September 2, 1908) and C. Matlack Price, “The Development of a National Architecture: The Work of Grosvenor Atterbury.” Arts and Decoration 2:5 (March 1912): 176-179.

[4] James D. Van Trump, “Henry Phipps and the Phipps Conservatory,” Carnegie Magazine 50:1 (January 1976), 31, had credited Atterbury, who designed the Phipps Houses in New York in 1905 (and later), with the design of the demolished Phipps Model Tenement erected in Allegheny 1906-08. The building was designed by Alfred C. Bossom (1881-1965) and the drawings were executed in Atterbury’s office.

[5] The Brickbuilder 13 (June 1904), 131; 14 (October 1905), 236; “Bessemer Building interior, Grosvenor Atterbury,” Ohio Architect & Builder 14:6 (December 1909): 42.

[6] James D. Van Trump and Arthur P. Ziegler, Jr., Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 1966): 53.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Fulton Building,” James D. Van Trump Notecards, Van Trump Papers, James D. Van Trump Library, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

[9] Construction 3:3 (January 20, 1906): “Henry Phipps has approved the plans for a fourteen-story building on his Duquesne Way property in the rear of the Bessemer Building. The plans were drawn by a New York architect. It is expected that work will be started by April 1st. The plot has a frontage of 120 feet on Duquesne Way. The new building will be on the site of the present natatorium building and it is said that another natatorium will be constructed in the rear of the fourteen-story building. The big building will be used for storage and light manufacturing purposes.” [53]

[10] “Downtown Landmark Soon to Be Torn Down,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 29 February 1956.

[11] James Van Trump, “Jamie’s Journal: The Great Unwashed,” Pittsburgher Magazine (October 1980), 19-20. See also “The Pittsburgh Natatorium, Pittsburgh, PA,” The Builder 27:7 (October 1909), 40; 1 unnumbered plate.

[12] “Phipps Natatorium,” Janet Parks and Allen G. Neumann, The Old World Builds the New: The Guastavino Company and the Technology of the Catalan Vault 1885-1962 (Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, 1996), 93.

[13] G. Atterbury, “Model Towns in America,” Scribner’s Magazine 52:1 (July 1912), 20-35; Samuel Howe, “A Forerunner of the Future Suburb: The Growing Popular Appreciation of the Picturesque in Domestic Architecture,” Arts and Decoration 2:12 (October 1912), 414, 419-422; Susan L. Klaus, A Modern Arcadia: Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and the Plan for Forest Hills Gardens (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press), 2002; Laurence Veiller, “Industrial housing developments in America. Part IV: A Colony in the Blue Ridge Mountains at Erwin Tenn.: Grosvenor Atterbury, Architect and Town Planner,” Architectural Record 53:6 (June 1918), 547-559; Margaret Crawford, Building the Workingman’s Paradise: The Design of the American Company Town (New York: Verso, 1995, chap. 6). John L. Fox, Housing for the Working Classes: Henry Phipps from the Carnegie Steel Company to Phipps Houses (Larchmont, NY, 2007).

[14] In addition to Schaffer, Daniel H. Burnham (2003), see Sarah Bradford Landau, George P. Post, Architect (New York: Monacelli Press, 1998) and Walter C. Kidney, Henry Hornbostel: An Architect’s Master Touch (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 2002).

[15] Dwyer, “Grosvenor Atterbury,” 57.

-

Architecture Feature: The Buhl Building

By Albert M. Tannler

The Buhl Building, at 204 Fifth Avenue in downtown Pittsburgh, was designed in 1913 by Pittsburgh architect Benno Janssen (1874-1964), who also designed the white terra cotta addition to Kaufmann’s Department Store in 1913, Pittsburgh’s William Penn Hotel, the Pittsburgh Athletic Association, and Mellon Institute in Oakland, Longue Vue Club in Penn Hills, the E. J. Kaufmann, Sr. house in Fox Chapel, Rolling Rock Stables in Ligonier, and the B. D. Phillips house in Butler.

In Landmark Architecture (1985), PHLF’s architectural historian Walter C. Kidney wrote:

“This is a little gem of a building, clad in blue-creamy-white terra cotta thickly decorated with Renaissance motifs. The color contrast recalls Italian sgraffito work, in which an outer layer of stucco is cut away while still fresh to reveal . . . an inner layer in a contrasting hue. The ground floor has been altered in a Moderne manner.”

In 2009, N & P Properties, LLC, who own the building, undertook a restoration of the upper façade, a refurbishment and reconstruction of the first floor, and construction of a Market Street addition.

As the Moderne façade was removed from the first floor of the Buhl Building, sections of blue and white terra cotta were revealed and above the doorway the original name of the building was visible: Bash Building.

The Buhl Building is in the 1975 Downtown Survey conducted by Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation (PHLF). The survey form stated: “First called the Bash Building, this structure was under construction by mid-1913. Henry Buhl, Jr., bought it in October 1913 while it was still under construction.”

There is no information on the building in the Benno Janssen papers at the Carnegie Mellon University Architecture Archives so I assembled a chronological history of the building using plat maps, city directories, census records, newspapers, and deeds, assisted by researcher John Husack, who was documenting the history of Market Square for PHLF.

Architectural historians Lu Donnelly and Martin Aurand directed me to The Jewish Criterion (1862-1965), available online at http://pjn.library.cmu.edu, which proved to be invaluable. I used both hardcopy and the searchable database of city directories prior to 1940 on the Historic Pittsburgh website at http://digital.library.pitt.edu/pittsburgh. City newspapers were read on microfilm at the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

Here’s what we found.

Real estate mogul Franklin Felix Nicola (1859-1938) is known primarily, Walter Kidney tells us, for his “Bellefield and Schenley Farms development companies [that] transformed a large area in Oakland and provided a setting for much of the city’s best architecture.” On February 2, 1900, Nicola purchased the land and commercial buildings at 200-208 Fifth Avenue.

In 1906 Morris H. Bash opened a fur salon at 202 Fifth Avenue. Bash, who also sold women’s clothing and had a second location at 437 Smithfield Street, operated his businesses with his sons Henry, Louis, and William. Beginning in 1908, the firm is known as M. H. Bash Sons.

On January 30, 1913, Nicola announced that the 200-208 Fifth Ave buildings would be demolished on May 1, 1913, and construction would begin on a new building designed by Benno Janssen. Bash Sons paid for half the cost of constructing the new building and all furnishings; consequently the building would be named the Bash Building. As the principal tenants, Bash Sons were permitted to sublet the space they did not occupy in the building.

On August 11, 1913, while the building was being constructed by James L Stuart Company, Henry Buhl, Jr. purchased the property from Frank Nicola.

Advertisements—illustrated by a perspective drawing—of “The New Home of M.H. Bash Sons” appeared in Pittsburgh newspapers the second week in October. The Bash Building opened on October 13, 1913. In late 1915 or early 1916 the Bash firm declared bankruptcy. Their stock was liquidated by the Frank & Seder Department Store.

From 1917 to 1921, both names—Bash Building and Buhl Building, 204 Fifth Avenue—were listed in city directories. In 1922 the building became the Buhl Building. Henry Bash was able to remain in business and he retained a retail space in the Buhl, née Bash, Building for some years thereafter.

N &P Properties, LLC will donate a preservation easement on the Buhl Building to PHLF guaranteeing that the Buhl Building façade will be preserved for future generations.

-

Free Guided Tours of Historic Oakmont Country Club

Mondays, from 8:45 a.m. – 10:30 a.m.

- April 10 and 24

- May 1 and 15

- June 5 and 19

- July 10 and 24

- August 7 and 21

- September 11 and 25

- October 9 and 23

- November 6 and 20

- December 4 and 18

The tour is free. Donations are welcome, with the proceeds going to the Oakmont Country Club (OCC) Archives Committee to further advance the tour experience.

Advance reservations are required; limit of twelve individuals per tour.

For reservations, contact Oakmont Country Club: 412-828-8000

Few golf courses in the world have the fabled history of Oakmont Country Club, a National Historic Landmark and host of nineteen major championships to date. Now, you can tour the historic clubhouse and golf course on certain Monday mornings, April through December.

Participants will be guided through our handsomely preserved 113-year-old clubhouse by one of our golf historians. Learn about the founding of the club in 1903 and the family that made it all possible. A stroll down History Hall illustrates the history of the US Open at Oakmont, with historic photographs, memorabilia, and championship artifacts. Gaze upon our collection of USGA trophies and see the original men’s locker room.

Weather permitting, guests will tour the historic “inland links” golf course and see the extraordinary vistas, narrow fairways, treacherous sand bunkers, and iconic “Church Pew” bunker. Guests will also have the opportunity to test their putting skills on Oakmont’s world-renowned putting surfaces.

The tour ends at the Oakmont Professional Shop, where guests may browse through a wonderful selection of apparel, equipment, and memorabilia only available at Oakmont Country Club.

Additional details:

- Please arrive at Oakmont Country Club by 8:45 a.m. (light refreshments provided)

- Casual attire (no jeans or denim) and comfortable walking shoes with flat sole. Coat or jacket depending on weather forecast. Umbrellas will be provided.

- Disabled access is available.

- Photography is permitted.

- For further information about the tour, contact the OCC Archives: 412-828-8000, ext. 257 or archives@gmail.com

Tours are sponsored by the Fownes Foundation, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to the restoration and preservation of nationally recognized, historically significant golf sites.

-

A Young Preservationist Determined to Learn a Trade

By Haley Roberts

Haley Roberts, on the far right in the picture, spent an academic year as a Landmarks Fellow at PHLF, and recently took a preservation demonstration course on restoring windows.

I have been an advocate for historic preservation for many years. I can talk anyone’s ear off about the historical significance of a place, and I can run an economic analysis to prove that a historic structure is a good investment for families or developers. However, in spite of those valuable skills, I still felt hypocritical in demanding the preservation of historic properties in Pittsburgh for one very good reason.

I could not actually DO historic preservation.

By that, I mean that I had no experience in the preservation trades like plaster repair, repointing masonry, or—my personal interest—wood window restoration. How could I possibly expect Pittsburgh residents to be good stewards of their historic homes if I had no idea how to maintain them myself?

I became determined to learn a trade. I chose to tackle window restoration specifically because windows, in my opinion, are the eyes into the soul of a home. Through them, people can see the spirit, passion, and craftsmanship that was poured into the construction of an older building. However, with an ever-decreasing supply of window restoration specialists, original wood windows in historic homes are at risk for being swapped out for vinyl replacements. When that occurs, these homes lose a significant part of their charm.

In trying to learn about wood windows through YouTube videos and blogs, I stumbled across the Historic Homes Workshop, an event in Tampa hosted by a local window restoration company called Wood Window Makeover that teaches people, step by step, how to repair wood windows. This nine-day intensive training consisted of two “classroom” days – one to learn the process of restoring a window, and the other to become an EPA-certified renovator – and two multi-day, hands-on projects where I put my knowledge to the test under the mentorship of window restorers from across the country.

During the workshop, I pulled window sashes out of their frames and restored the functionality of their rope and pulley mechanisms. I scraped layers of paint off of 100 year-old window jambs. I took wavy glass panes out of these windows and re-glazed them. I even learned to paint without painter’s tape and to use lots of different saws! All the while, I was networking with preservationists in Michigan, Ohio, Florida, Georgia, and many other states who shared their experiences, tactics, and struggles in protecting historic architecture in their hometowns.

I was thrilled to develop all of these skills and meet new people, but perhaps the most valuable thing I walked away with from the Historic Homes Workshop was an appreciation for the love and craftsmanship that went into wood windows when they were originally installed. I would have never known how rewarding working on windows can be without this hands-on experience. It only made my passion for historic preservation that much stronger.

As a result of the Historic Homes Workshop in Tampa, I feel confident that I can restore historic wood windows from start to finish. I cannot wait to start sharing my knowledge and advancing historic preservation efforts through preservation-specific trades here in Pittsburgh.

-

Featuring Architect William George Burns

This is the best preserved of the large Pittsburgh railway stations still extant [containing] some 80,000 feet of floor space. . . . Designed in 1898 by William George Burns, it was completed in 1901. . . . On the interior the great waiting room is undoubtedly, after the foyer of the Carnegie Music Hall, the finest Edwardian space extant in Pittsburgh. The staircase that descends into the room like a waterfall is especially noteworthy and the ornate detail that adorns this great two-story hall contributes a general air of subdued cruscating [sparkling] richness to the whole convoluted space. Every effort should be made to preserve this elegant structure. —— James D. Van Trump, Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (1967)

This is the best preserved of the large Pittsburgh railway stations still extant [containing] some 80,000 feet of floor space. . . . Designed in 1898 by William George Burns, it was completed in 1901. . . . On the interior the great waiting room is undoubtedly, after the foyer of the Carnegie Music Hall, the finest Edwardian space extant in Pittsburgh. The staircase that descends into the room like a waterfall is especially noteworthy and the ornate detail that adorns this great two-story hall contributes a general air of subdued cruscating [sparkling] richness to the whole convoluted space. Every effort should be made to preserve this elegant structure. —— James D. Van Trump, Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (1967)By Albert M. Tannler

PHLF Historical Collections DirectorIn the main, William George Burns should be considered a Canadian architect. He was born in Toronto, Canada, on either August 1, 1870 (according to Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1850-1950 (2009-2016) or in July 1871 (according to US Federal Census 1900), worked as a carpenter in Toronto in 1887, worked as an apprentice to architect Mancel Willmot (1853-1934) from 1888-1892 and subsequently worked as a draftsman for architect William G. Storm (1826-1892).

Burns came to America either in 1892 (according to the 1900 Federal Census) or in 1895 (according to Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950) which states “He left Canada in 1895 and went to New York City where he obtained further education before moving to Pittsburgh, Penn.” Burns’ work in Pittsburgh has been documented and spans 1898-1904. He first appears in Pittsburgh directories in 1899 in two entries: Wm G. Burns is listed as a draftsman, living at 12 Stockton Avenue, Allegheny, while G. W. Burns, architect, appears at the same address. He resided in Allegheny (1899), Beaver (1900), and Sewickley (1901-04). In 1901 Burns formed a partnership with Charles H. Craig and Harvey Childs Hodgens in the firm of Craig, Hodgens & Burns (1901-02), later Hodgens & Burns (1903-04).

Three of Burns’ projects in Western Pennsylvania have been documented: the Lincoln Hotel, (demolished); the John Snyder residence, Beaver, Pa., 1901; and the first and most important: the P&LE RR Station in Pittsburgh, 1898-1901.

Biographical Dictionary of Architects in Canada 1800-1950 notes that Burns “was fortunate enough to obtain a position as Staff Architect for the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Rail Road in 1899 and was given the opportunity to design the P. & L.E. Railroad Station, Smithfield Street at Carson Street, PITTSBURGH, PENN., 1898-1901. . . . The significant Beaux-Arts landmark integrated commercial offices, passenger arrival and departure halls, and train sheds into one complex, and the Grand Concourse is now considered one of the finest interior public spaces in Pittsburgh.” The waiting room was decorated by Crossman & Sturdy, 287 Michigan Ave., a Chicago firm established in 1893. Their design for the P.&L.E. waiting room was published in the 1900 and 1903 Pittsburgh Architectural Club Exhibition catalogs.

Around 1905 Burns returned to Toronto and opened his own architecture practice. Among his documented works between 1905 and 1916 are nine houses (including his own); two churches and a Sunday school; and a factory. He left the architectural profession after 1922 and worked in real estate and construction before retiring. He died on November 23, 1949.

-

Scholarship Opportunity for High School Seniors

Thanks to funding support from PHLF’s Brashear Family Named Fund, the McSwigan Family Foundation, and many other donors, PHLF offers a scholarship program for high-achieving, community-minded, high-school seniors in Allegheny County who will be attending college or university in the fall of 2017.

“The Landmarks Scholarship recognizes students who have achieved academic excellence and possess the potential to make a difference in the Pittsburgh community and beyond,” said David Brashear, a PHLF trustee and the program founder. “The students selected by our committee already feel connected to the city and its history and will hopefully continue to serve the region as leaders in promoting PHLF’s values.”

Since 1999, PHLF has awarded scholarships to 64 students who care deeply about the Pittsburgh region. The scholarship award of $6,000, payable over four years to the recipient’s college or university, is for book and tuition expenses only.

Click here to learn more about the eligibility requirements and criteria and to download an application. The application deadline is Wednesday, April 19, 2017.

-

“Portable Pittsburgh” Builds Hometown Pride and Knowledge

“The children really need an understanding of where they live in this world. Portable Pittsburgh supplements our unit studies.” ––Pittsburgh Public School teacher

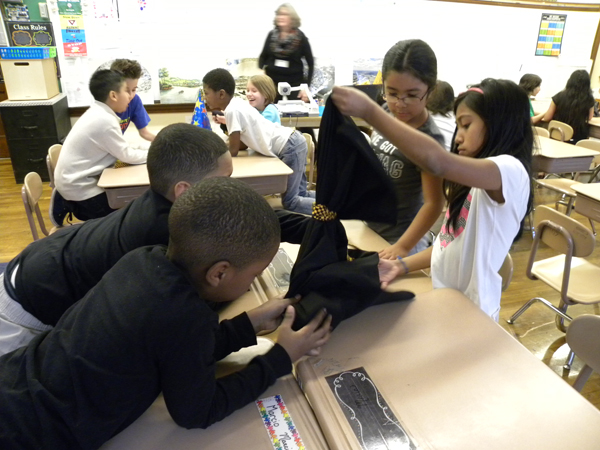

Karen Cahall, PHLF’s education coordinator, helps third-grade students understand how Pittsburgh has grown and changed over time by having them unwrap “mystery artifacts” and by showing them images of Pittsburgh from 1765 until 2014. Through her hands-on discussion and interactive presentation, students are able to “visualize the progression of time in Pittsburgh and understand how people lived throughout the years,” according to one teacher.

Portable Pittsburgh is one of the programs PHLF presents to Pittsburgh Public Schools through its “Building Pride/Building Character” program, offered through the state’s Educational Improvement Tax Credit (EITC) program. Contributions from the following corporations and private foundations are funding PHLF’s programming in 2016-17:

Lead:

- First National Bank of Pennsylvania

- McSwigan Family Foundation

- Alfred M. Oppenheimer Memorial Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation

- PNC Bank

Patrons:

- Eat’n Park Hospitality Group, Inc.

- Frank B. Fuhrer Wholesale Company

- Huntington Bank

Partners:

- Hefren-Tillotson, Inc.

- Maher Duessel, CPA

- C. S. McKee, LP

- UPMC