In a Former Lutheran Church in East Pittsburgh, an Artist Crafts a Home and Studio

Here’s the church.

Up there was the steeple.

Open it up and there’s … no people.

Unless, of course, it’s party time at Dan Riccobon’s house, the former Emanuel Lutheran Church in East Pittsburgh.

He bought the brick building in 1998 from a congregation that by then had dwindled to about 40 elderly members, and he’s spent much of his free time over the past dozen years converting it into his home and studio.

It’s an artful renovation to which Giordano Riccobon has brought his woodworking, ceramic and decorative painting skills and an aesthetic inspired by trips to Venice and his native Trieste.

After World War II, his family’s farm overlooking the Adriatic Sea fell on the Yugoslavian side of the Morgan Line demarcation.

“They just came one day and told my dad he had to go. We could wait 10 years for housing or go to the United States,” where an aunt and uncle awaited them in Pittsburgh.

Mario Riccobon, his pregnant wife Silvia and their four children immigrated in 1951.

“A lot of what I do, whether it’s in the building here or in my artwork, is rooted in the continuous lineage of history,” he said, a commitment reinforced on return visits to Italy’s ancient steps and fountains worn smooth, where he overhears the same conversations from Italians perched on them.

“It’s one never-ending ribbon of time.”

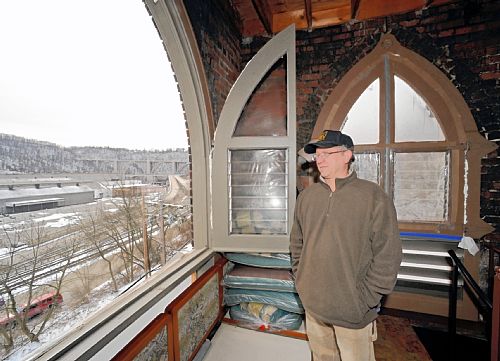

Dan Riccobon converted the bell tower into a small sitting area reached by a spiral stairway that overlooks the former Westinghouse plant. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

In East Pittsburgh, acting as architect, contractor, carpenter and interior designer, Mr. Riccobon has done most of the work himself, from removing the rotting steeple to building the bathroom and kitchen to painting the ceiling of the nave, on his back on a scaffold, with the constellations and the creatures that inspired them.

The result is a sweet, magical, handcrafted space suffused with warmth and a playful spirit of creativity.

“I was giddy when I first moved in,” said Mr. Riccobon, a painter and retired Woodland Hills art teacher.

By then, some of the biggest jobs were behind him, including rewiring the building, vacuuming soot from the attic and insulating it, and installing a shower in the basement.

“It was a long two years traveling back and forth working on the weekends, I can tell you that.”

But what a difference.

For more than 20 years, “I lived in Regent Square in a little tiny third-floor apartment you could hardly stand up in.”

The congregation that built Emanuel Lutheran Church pretty much lived and died with the Westinghouse plant just across the street.

Westinghouse Electric built its primary plant in East Pittsburgh in the Turtle Creek Valley in 1895, making electric railway motors, generators, switches and other railway equipment. Two years later, German immigrants founded Die Reformations Gemeinde and built a frame church on a narrow, elevated triangle of land on Linden Avenue, then a bustling commercial street.

In 1923, the church was demolished and the triangle leveled to build the new brick church. The congregation sold the building 75 years later, a decade after the Westinghouse plant closed in 1988.

When Mr. Riccobon bought the church, the whole interior was painted white. When some of the paint began to peel, he discovered a decorative border just beneath the ceiling. He made a stencil from the fragment and restored the entire border, along with the church’s ochre-toned walls.

He’s also kept the painted angels-on-canvas that flank the apse, where his 15-foot balsam fir Christmas tree still soars.

The former sanctuary is now a large open living space, with the old altar making home for a huge Christmas tree. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

The nave — the large open area that makes up most of the interior — holds Mr. Riccobon’s living space, with two sitting areas and a dining table near the new kitchen.

Until last June, he used the larger kitchen in the basement but tired of running up and down steps to prepare meals. So he turned the church’s coat closet into his new kitchen, building the Craftsman-style cabinets from scratch using beadboard paneling from Construction Junction. The marble countertops, once part of the wall of a bank, came from CJ, too, as did the Carrara glass back splash.

“It’s a two-way street,” Mr. Riccobon said. “I deliver stuff, too, from here. I’ve taken over doors and sinks I’ve removed.”

The former sanctuary is now a large open living space, with the kitchen tucked into a corner under the former choir loft. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

At a friend’s urging, he replaced several panes of the stained glass window above the kitchen sink with clear glass. Now he has a view of the Westinghouse Bridge.

The former choir loft is his bedroom, with a homemade Murphy bed and a wall of IKEA cupboards painted to resemble an old Venetian screen.

But the showstopper is the adjacent tiled bathroom and its ogee-arch shower opening. He made the turquoise tiles that frame it, glazing and firing them along with student work at Woodland Hills High.

The bathroom’s curved wall (and curved interior windows; that was a challenge) was ordained by the circular staircase he installed to get to the bell tower, now a summer sitting area with sweeping views of the valley. Higher still and accessible by ladder is the open deck that held the steeple.

The huge basement houses Mr. Riccobon’s painting studio, where he produces large-scale canvases based on his photographs of Venetian architecture. He uses some of the same techniques as in his decorative painting, creating built-up surfaces with a patina of antiquity.

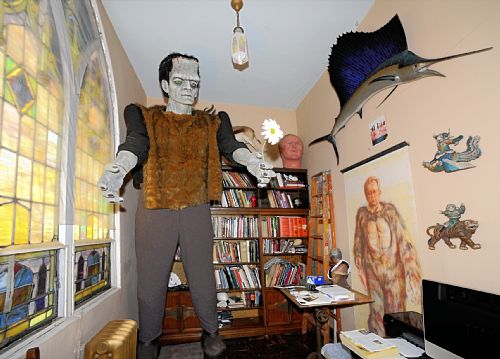

For a dozen years Mr. Riccobon had a studio in Oakland, where he worked on sets and costumes for the late Don Brockett’s productions. The Jack Lambert head atop the library’s bookshelves is a relic of that era.

He made the big harlequin head mounted on the west wall for a Mardi Gras party he threw in 2000 for the teachers he’d worked with at several Woodland Hills schools. He created the King Kong head and the 11-foot-tall Frankenstein that looms over the library alcove for one of his Halloween parties.

For Mr. Riccobon, the best part of having home and studio in the same building is not the easy commute but having work in progress so close at hand.

There’s an advantage to “being able to look at what you’re working on as you walk by, rather than leaving it and not beginning to think about it until you see it again,” he said. “As an artist, about 80 percent of the work you do is thinking about it, judgmental things, rather than the actual painting.”

A small room off the former alter is an eclectic mix of his art, including Frankenstein, Jack Lambert's head and a painting of Riccobon in a gorilla suit. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

He has a word of caution for anyone considering buying a church for living space. Before you can bid on the building, he said, you’ll need a mortgage approval, and to get that you’ll need an architect’s renovation drawings and a contractor.

He ended up taking another route, paying with cash socked away during all those years living in the third-floor walk-up. That left him little money for the major renovation he’d been contemplating, but that turned out to be a good thing.

“It allowed me to live here and get a feel for what I needed,” he said. “If I hadn’t, it would have been a disaster. I had thoughts of putting in a second floor.

“What I finally decided I should do is make everything look like it belonged here in the beginning,” he said. “Nothing’s nicer than these giant ceilings.”