Concrete Bridges of the Steel City

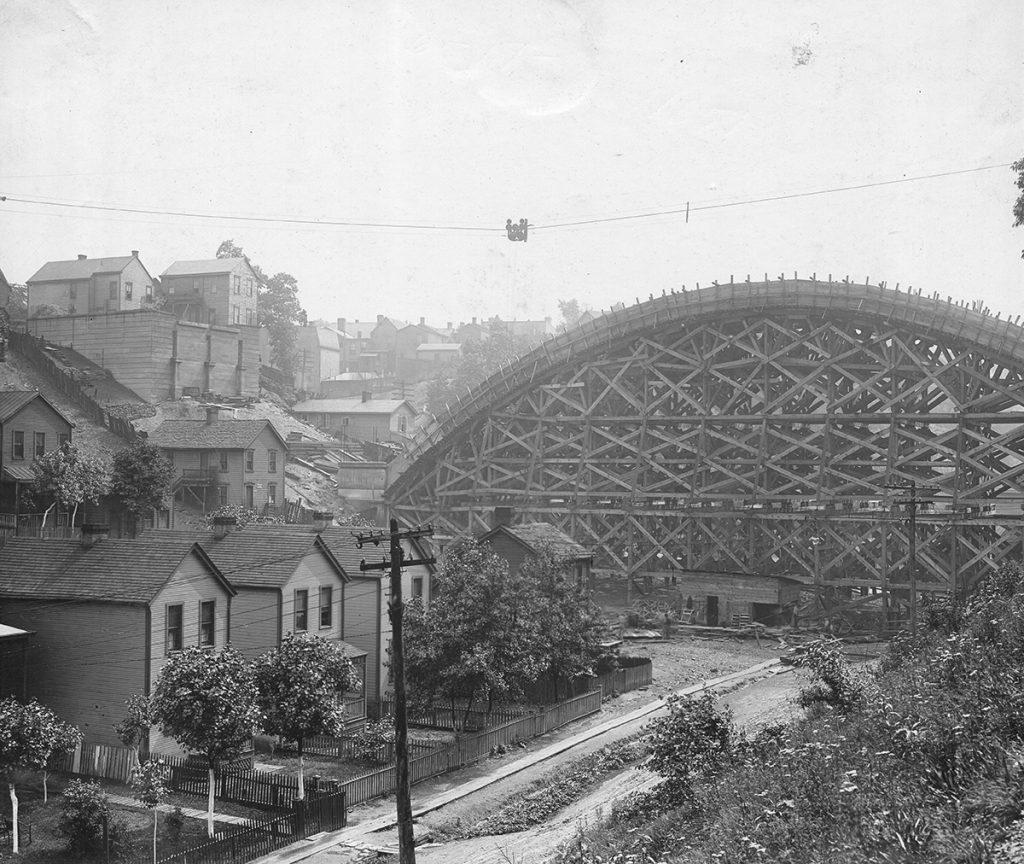

Construction of the Meadow Street Bridge in June 1910, with wooden falsework towering over the valley and the concrete arch starting to take shape. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

By Todd Wilson

While Pittsburgh may be known as “The Steel City,” many beautiful and significant concrete bridges were built here. Concrete is a rock-like mixture of fine and coarse aggregates (sand, gravel, stone) pasted together with a binder made up of Portland cement and water. Replacing natural cement, Portland cement (named for its resemblance to Portland stone from the Isle of Portland in England) is made from limestone, clay, and gypsum.

Portland cement was patented in 1824 and first manufactured in America in Lehigh County in 1871. As with stone structures, concrete is strong when compressed, but it is much weaker when being pulled apart in tension. A few concrete arch bridges started to be built in America in the 1870s, though it was not until steel reinforcement began to be added to concrete to withstand tensile forces starting around 1890, that the true potential of concrete structures could start to be realized.

The first large-scale concrete arch bridge was Luxembourg’s 1904 Pont Adolphe, with open spandrel walls and a 278-foot main span. Impressed, Philadelphia built a similar bridge in 1908, the Walnut Lane Bridge in Fairmount Park, having a 233-foot main span. Adorned with City Beautiful embellishments, it showcased how concrete could be used as an architectural material especially appropriate for parklike settings. The soaring arch avoided the need for intermediate supports infringing into the valley below, and using concrete instead of stone allowed for a more economical bridge with a longer span.

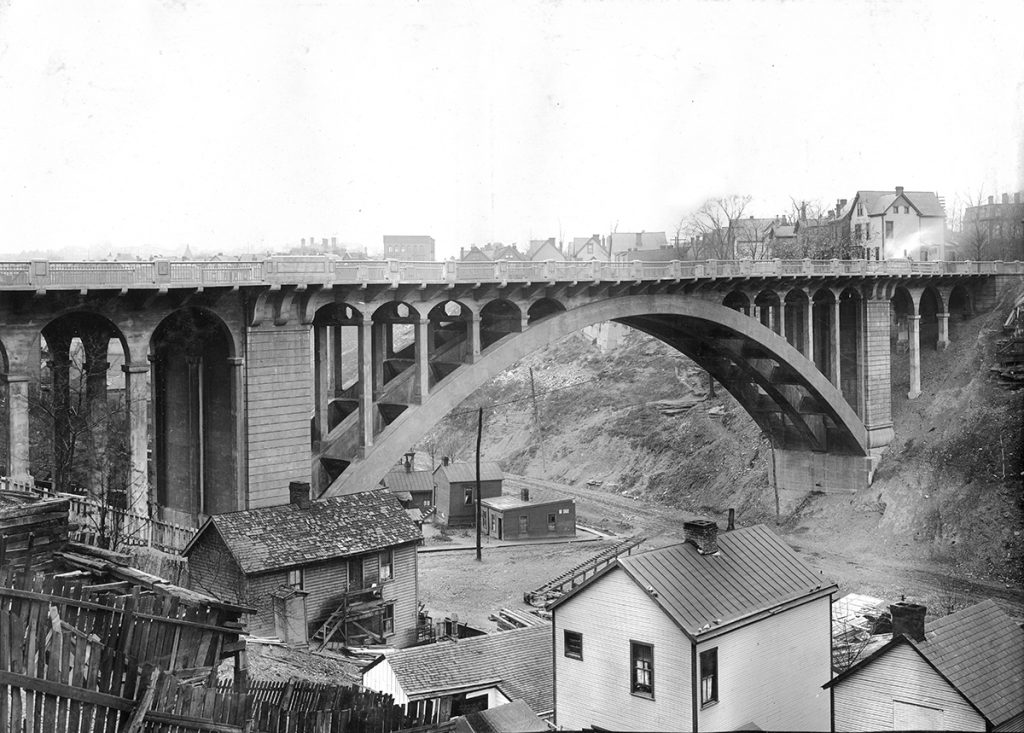

By November 1910 work was wrapping up on the ornate Meadow Street Bridge. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

The Walnut Lane Bridge was widely promoted in engineering literature of the day, and cities like Pittsburgh were quick to build similar structures. Locally, while utilitarian bridges continued to be built for typical ravine crossings, for a 40-year period beginning in 1910, concrete arch bridge designs were chosen for structures in parks, along boulevards and parkways, and at other prominent locations.

In the early 1900s, Pittsburgh was hoping to incorporate the valleys of the Negley Run watershed into Highland Park, where present-day Negley Run Boulevard and Washington Boulevard are located. This became the perfect location for the Pittsburgh Department of Public Works to experiment with concrete arch bridges. The city’s first bridge was built across present-day Negley Run Boulevard, extending Meadow Street from Larimer northward to the intersection of Stanton Avenue and Heberton Street in Highland Park.

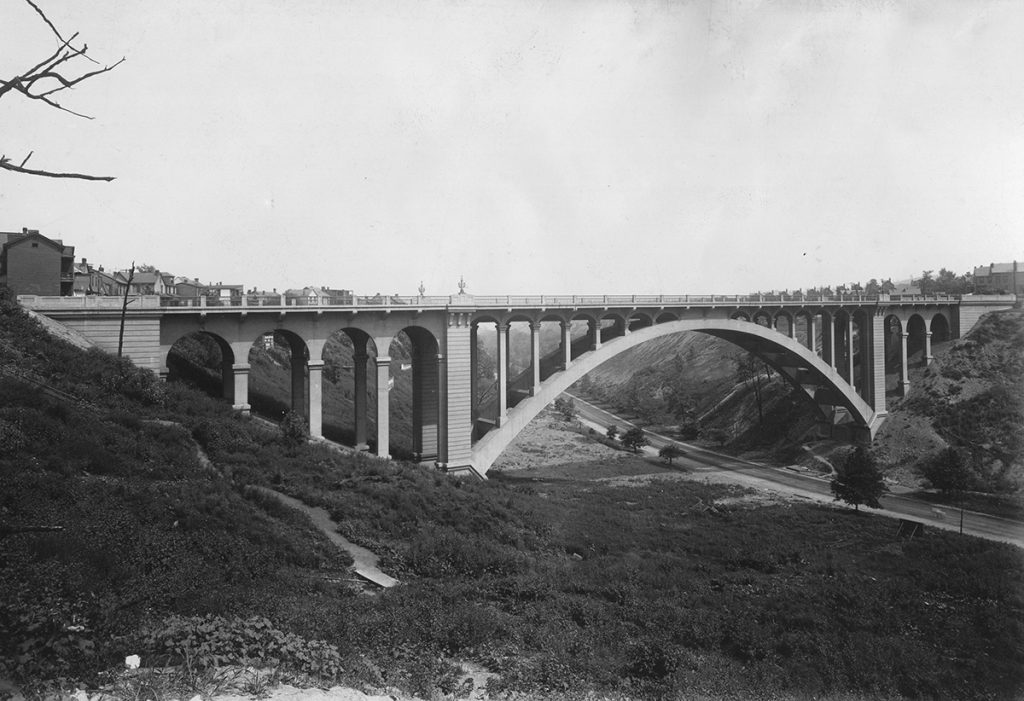

Featuring decorative lampposts, paneled parapets, and other City Beautiful-era neoclassical details, the Meadow Street Bridge was built in 1910 with a 208-foot arch. From 1911 to 1912, the City replaced the Larimer Avenue streetcar viaduct over Washington Boulevard with a 300-foot arch, which according to its plaque, was the second longest arch bridge in the world upon completion in 1912 (presumably after New Zealand’s 1910 320-foot Grafton Bridge). A decorative plaque is located under the arch that was intended to be a monument along a park trail that was never built. The Larimer Avenue Bridge was determined to be historically significant in Pennsylvania’s first historic bridge survey in the 1980s and was awarded a Historic Landmark Plaque by Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation in 2019.

The Meadow Street Bridge as it looks today. During its 1962-63 rehabilitation, the entire structure above the arch ribs was replaced. Source: Todd Wilson.

With the initial success of these first two open spandrel reinforced concrete arch bridges, the City of Pittsburgh Public Works Department built several more within the next few years—on Baum Boulevard over Junction Hollow between Bloomfield and Oakland (1913), on Murray Avenue over Beechwood Boulevard between Squirrel Hill and Greenfield (1914), on Washington Boulevard over Heth’s Run in Highland Park (1914), on Beechwood Boulevard over the Four Mile Run Valley entering Schenley Park (1923), and on P.J. McArdle Roadway over Sycamore Street along the Mt. Washington hillside (1928). Stanley Roush served as the architect for these bridges.

The city also built a large three-span solid spandrel concrete arch on Baum Boulevard over the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1913, with the design chosen due to the long, shallow ravine that was more suitable for multiple smaller arches. While the other concrete arch bridges used wooden falsework for arch centering to hold the concrete forms, this bridge used Blawforms, self-supporting steel arch centering, that held the formwork in place without obstructing the railroad below. They were made by the company, which started in 1906 as the Blaw Collapsible Steel Centering Company, and merged in 1917 to become the Blaw-Knox Company. Many of these Blawforms forms manufactured in Blawnox were used to construct major concrete arch bridges all over the country.

Most of the city’s grand concrete bridges were built under Mayor Joseph Armstrong’s administration (1914-1918), first with neoclassical that transitioned to Art Deco detailing by Stanley Roush. When Armstrong became a County Commissioner in 1924, he led a massive road and building campaign that included the construction of record-breaking open spandrel concrete arch bridges.

This August 1913 photograph shows the newly-completed Larimer Avenue Bridge over the undeveloped part of the Negley Run ravine that the city unsuccessfully wanted to incorporate into Highland Park. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

These included the 320-foot California Avenue Bridge over Jacks Run (1925), the John P. Moore Bridge over Bausman Street in Knoxville (1928), and six Ohio River Boulevard bridges, the largest being the 420-foot arch over Jacks Run (1931). The cumulation of Allegheny County’s concrete arch building campaign was the five-span George Westinghouse Memorial Bridge over Turtle Creek with its record-breaking 460-foot central arch (1932). The bridge was awarded a PHLF Landmark Plaque in 1984. The last major reinforced concrete arch to be built in Pittsburgh was the 1952 Penn-Lincoln Parkway East Bridge over Nine Mile Run in Frick Park by the Pennsylvania Department of Highways.

While reinforced concrete bridges were once marketed as long-lasting “permanent” bridges, the expectation of concrete being a maintenance-free material proved to be unrealistic, often due to moisture penetrating through the concrete to the steel reinforcement. Concrete spalling was observed on some of the city’s bridges within 15 years of opening, and by the 1960s the Meadow Street Bridge had to be entirely rebuilt above the arch ribs.

The George Westinghouse Memorial Bridge, designed by architect Stanley Roush and engineers Vernon Covell and George S. Richardson opened in 1932. Its 460-foot central arch was the largest built at that time. Source: Todd Wilson.

In the 1970s and 1980s, just about every arch bridge was either rehabilitated or replaced, and continued deterioration led to the demolition of two City-built bridges in the 2010s. Among the City-built structures, only the Meadow Street arch ribs and the Larimer Avenue Bridge still survive. The newer County-built bridges fared better, with only the John P. Moore Bridge and the Ohio River Boulevard over Jacks Run Bridge having been demolished. However, many of the remaining bridges are showing signs of deterioration and have weight restrictions, and they face an uncertain future if unable to successfully be repaired or to keep up with modern traffic demands.

Despite being built in a relatively short 40-year period, the Pittsburgh area’s reinforced concrete arch bridges were monuments to what a developing city aspired to become—one with grand structures promoting civic ideals beautifying parks, parkways, and boulevards. Built with innovative techniques and spanning record-breaking distances, Pittsburgh’s reinforced concrete arch bridges set the standard for what concrete arch bridges could become, as larger record-breaking examples continue to be built to this day.

This January 1913 photograph shows the Baum Boulevard Bridge over the Pennsylvania Railroad valley under construction, with the steel Blawforms supporting the arches without falsework in the valley below. Source: Department of Public Works, Division of Photography, City of Pittsburgh.

About the author: Todd Wilson, MBA, PE, is a transportation engineer in the Pittsburgh area who has traveled to all 50 states and over 25 countries photographing bridges. Having been awarded a Landmarks Scholarship to Carnegie Mellon University for his high school manuscript on Pittsburgh’s Bridges, he has since co-authored two books on the area’s bridges: Images of America: Pittsburgh’s Bridges (Arcadia, 2015) and Engineering Pittsburgh: A History of Roads, Rails, Canals, Bridges and More (History Press, 2018). He has won several awards, including being named one of Pittsburgh’s 40 under 40 and one of the American Society of Civil Engineers New Faces of Civil Engineering, and he serves as a Trustee of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.