Category Archive: PHLF News

-

A Tribute to D. William “Bill” Roberts (1931–2017)

Editor’s Note: Cathy McCollom, the director of River Town Program and the principal of McCollom Development Strategies, is a trustee of Landmarks Development Corporation and a former PHLF staff member. She wrote the following tribute to Bill Roberts who died on Saturday, April 22 at his home in Sewickley. Bill was a trustee of Landmarks Development Corporation and a former PHLF staff member. He was part of PHLF’s development of Station Square from the beginning, in the mid-1970s, after serving as a marketing director with the Pittsburgh Symphony and as an actual captain (and then marketing director) for the Gateway Clipper. He helped create the marketing plan for Station Square, which drew three million people annually to our historic, riverfront development in the early 1990s. As Cathy writes:

When I think of Bill Roberts, I think of two words: kindness and competence.

Before I moved to Pittsburgh from Louisville, Kentucky, Arthur Ziegler sent me to “connect with Bill Roberts” during the Regatta. Coming from where a lady’s proper dress for almost any affair, certainly something called a Regatta, included high heels and a hat, I arrived at the river at Point Park wearing just that. The park was brimming with vendors and people ––none of them in heels!––and the river was teeming with colorful boats. And out in one of those boats was Bill Roberts.

I picked my way carefully along the shore until I found an official looking guy with a radio who called for a boat to pick me up and take me to the middle of the river where I would meet Bill for the first time.

Bill had a radio in each hand and there was another one chirping on deck. Always a man of few words, he kindly refrained from commenting on my inappropriate attire. Instead, he helped me to a chair where I sat for the next several hours, totally amazed, and a bit intimidated, as Bill calmly and coolly solved crisis after crisis, and answered question after question, with high speed boats roaring around us all the while. It was an unforgettable introduction to the marketing and event planning acumen of Bill Roberts.

Bill was never critical, and rarely ruffled, despite what was often mayhem around him. He taught me how to ignore naysayers; how to organize, coordinate and plan; how to work with sponsors and partners to the mutual benefit of all. He taught me the best way to clean up after every event. And he did it all while remaining coolly competent and always kind.

I still follow his advice, and hopefully his example, to this day. Thirty years and hundreds of events later, I am still in awe of the guy who ran the Regatta.

-

Architecture feature: The Guastavino Company in Pittsburgh

By Albert M. Tannler

Last month we explored buildings in Pittsburgh designed by New York architect Grosvenor Atterbury. One of these, now gone, was the Phipps Natatorium (1907-09), 540 Duquesne Way, with tile work by the Guastavino Company, described as “a polychromed barrel vault with a regular circular geometry. A vaulted skylight system was integrated into the graceful lines of the circular arches.”[1]

Born and trained in Barcelona, Rafael Guastavino (1842-1908) is best known for his construction company in New York City, which used an adaptation of Catalan constructional methods to create shell vaulting and stairs of cohesive tiles hand-assembled in strong mortar. Rafael Guastavino, Jr. (1872-1950) continued the firm after his father’s death in 1908. Guastavino tile was very popular in early 20th-century monumental architecture.

It was George R. Collins, professor of the history of art and architecture at Columbia University, who rediscovered Guastavino tile.

As he sat in the back of the university’s St. Paul’s Chapel (1907) . . . on October 17, 1961, his eyes wandered to the ornate herringbone of tiles of the domed ceiling. The curves and colors reminded him of the work of the Catalan architect Antoni Gaudi (1852-1926), about whom he had recently completed a book. As he studied the ceiling, he suddenly realized that it used the same vaulting technology that Gaudi had deployed in many of his famous works in Barcelona.

This moment of discovery caused Collins to look more carefully at the architecture of the Upper West Side of Manhattan. . . . It seemed that nearly every block of New York City had a tile-vaulted space. Collins recognized that what looked like a decorative tile finish to the causal eye was actually a structural system of interlocking tiles, legendary in Spain for its ability to support tremendous loads with a remarkably small amount of material. . . . After years of studying Catalan art and architecture, Collins sensed that these [Guastavino] Spanish immigrants had a significant influence on American building construction, but it was not until he began to create an inventory of Guastavino tile vaulting that he fully appreciated the quality and importance of the company’s work. In May of 1962, Collins traveled to Pittsburgh to give a lecture, and he was astonished to find that thirty of the most significant buildings in the city contained Guastavino vaulting. These included major buildings at the local universities and many of the city government buildings, as well as numerous churches and synagogues.[2]

Patents

Guastavino filed three patents in 1885 for the construction of fireproof buildings, which marked the beginning of decades of patent applications by Guastavino and his son. The earliest patents helped Guastavino to gain credibility in the American building industry and pushed him toward a career as a building contractor specializing in vault construction rather than working as an architect.[3]

Pittsburgh architects

The Guastavino Company worked repeatedly with many architectural firms, the most notable being McKim, Mead, and White; Bertram Goodhue; Charles Haight; Cass Gilbert; Warren and Wetmore; and Henry Hornbostel.[4]

Among the architects who may be considered “Pittsburgh architects” were Henry Hornbostel, who commissioned five academic buildings, two synagogues, and the City-County Building in Pittsburgh as well as several bridges and arcades in New York. Parks and Neumann state: “Of all the architects who used the Guastavino Company, Hornbostel’s work is the most varied in the purely structural sense.”[5] Pittsburgh-based architects included Thomas Hannah; Alden & Harlow; Stanley L. Roush; E. B. Lee; A. F. Link; Benno Janssen and his partners Franklin Abbott and William Cocken; and Ingham & Boyd. E. P. Mellon was born and educated in Pittsburgh before moving to New York in his mid-30s. Twentieth-century Modern American Gothic architecture was represented by Ralph Adams Cram of Boston, Bertram Goodhue of New York and their partners, and Charles Z. Kauder and Wilson Eyre & Mcllvaine of Philadelphia. James W. Windrim of Philadelphia produced a late example of the American Renaissance. York & Sawyer and Trowbridge & Livingston were based in New York. Walter Kidney wrote about a “sober Modernistic manner that began and ended with allusions to Classical architecture” in Trowbridge & Livingston’s Gulf Building.

There are Guastavino tile buildings in Boston, New York, Washington, D. C. and elsewhere, but the range and diversity and character of buildings in Pittsburgh 1905-1942 suggests we focus on them.[6]

Academic buildings

Carnegie Mellon University Porter Hall, 1905-07; 1915, Henry Hornbostel

Carnegie Mellon University Doherty Hall, 1908-09

Carnegie Mellon University Hamerschlag Hall, 1914

Carnegie Mellon University Hamburg Hall, 1916

Carnegie Mellon University Baker Hall, 1919

Community College of Allegheny, West Hall, 1915, Thomas Hannah [Western Theological Seminary]

Chatham University Mellon Board Room, 1917, E. P. Mellon [A. W. Mellon residence]

University of Pittsburgh Heinz Memorial Chapel, 1934, Charles Z. Klauder

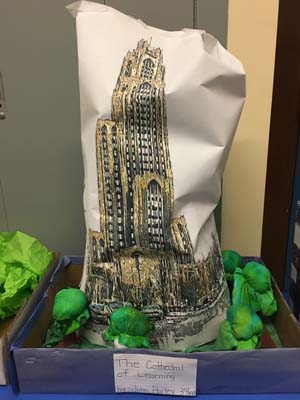

University of Pittsburgh Cathedral of Learning, 1937

University of Pittsburgh Stephen Foster Memorial, 1937

Ecclesiastical buildings

Calvary Episcopal Church, 1906, Ralph Adams Cram for Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson

Rodef Shalom Synagogue, 1906, Henry Hornbostel

First Baptist Church, 1911, Bertram G. Goodhue for Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson

B’Nai Israel Synagogue, 1924, Henry Hornbostel

St. Boniface R. C. Church, 1926, A. F. Link & Associates

Holy Rosary R. C. Church, 1929, Ralph Adams Cram for Cram & Ferguson

East Liberty Presbyterian Church, 1931-42, Ralph Adams Cram for Cram & Ferguson

Shadyside Presbyterian Church Addition, 1938, Wilson Eyre & McLlvaine

Government buildings

Allegheny County Courthouse alterations, 1911-13, Alden & Harlow; 1924-28, Stanley L. Roush

Pittsburgh City-County Building, 1916, E. B. Lee; Palmer and Hornbostel

[Federal] Post Office and Courthouse, 1931-34, Trowbridge & Livingston

Hotels

William Penn Hotel addition 1928, Janssen & Cocken

Clubs

Pittsburgh Athletic Association, 1910, Janssen & Abbott

Children’s Museum

Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh, 1938, Ingham & Boyd [Buhl Planetarium]

Hospitals

Allegheny General Hospital, 1915, Janssen & Abbott; York & Sawyer, 1929-31.

Public Utility

Bell Telephone Company Building addition, 1931, James Torrey Windrim

[1] Janet Parks, The Old World Builds the New, 93. Illustrated in John Ochsendorf, Guastavino Vaulting, 158.

[2] John Ochsendorf, Guastavino Vaulting, 8-9.

[3] Ochsendorf, 47.

[4] Janet Parks and Alan G. Neuman, 36.

[5] Ibid., 71.

[6] The Guastavino Company drawings, including Pittsburgh projects, are at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University. Three Pittsburgh buildings with Guastavino tile are known to have been demolished: as noted earlier, the Phipps Natatorium; the Central YWCA 1909 [59 Chatham Street]; and the R. B. Mellon residence, 1908-11, 6500 Fifth Avenue and Beechwood Boulevard (now Pittsburgh Garden Center and Mellon Park), Alden & Harlow. For the latter see Margaret Henderson Floyd, Architecture After Richardson: Regionalism before Modernism––Longfellow, Alden, and Harlow in Boston and Pittsburgh. Chicago: University of Chicago Press in association with the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 1994: 298-301. See also Mt. St. Peter Church Centennial: 100 Years of Faith 1904-2004 (Pittsburgh: Broudy Printing Inc., 2004).

-

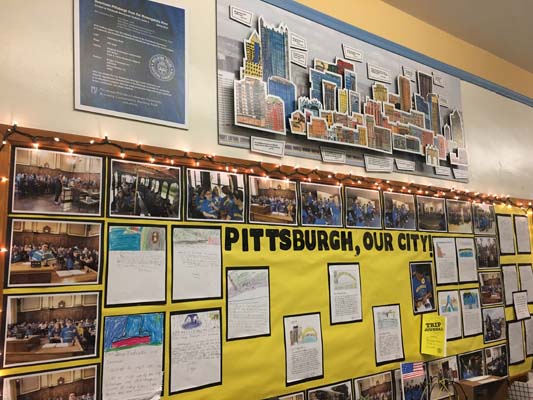

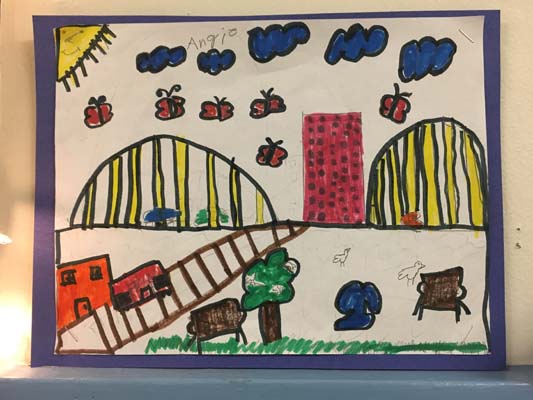

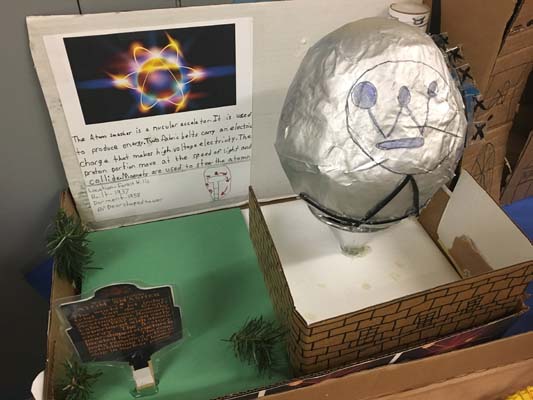

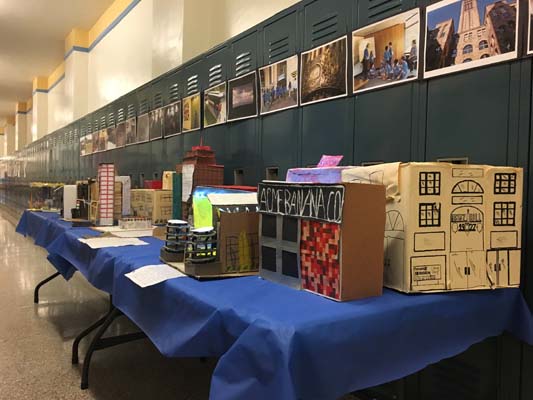

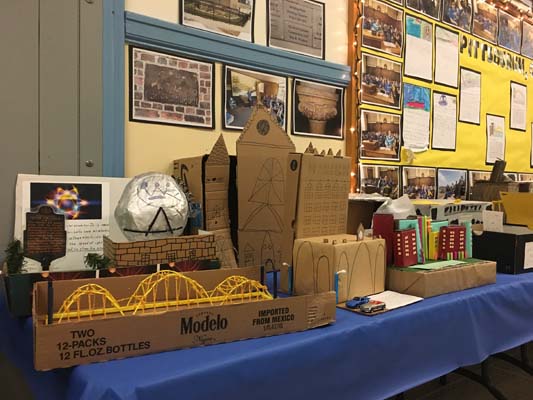

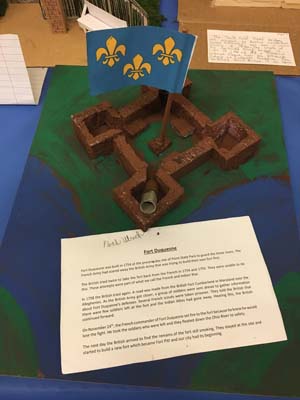

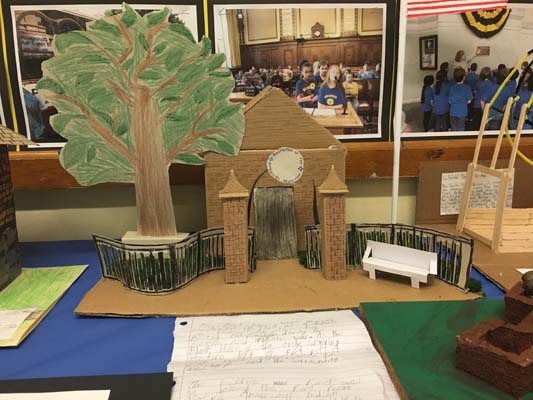

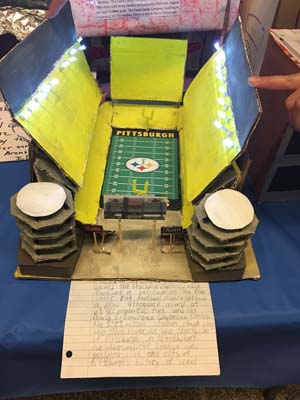

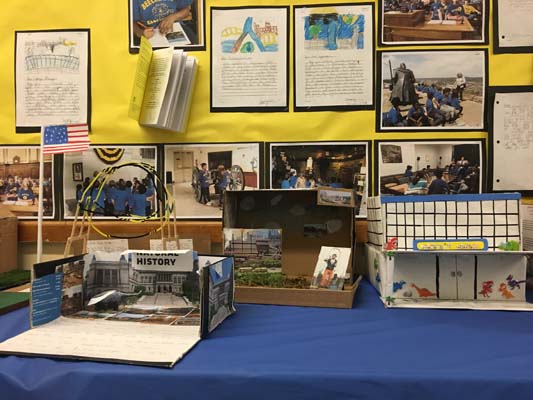

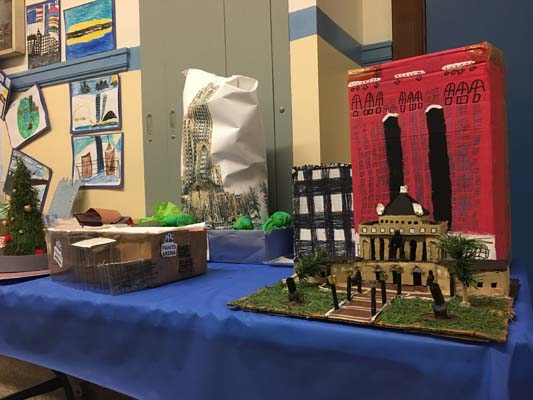

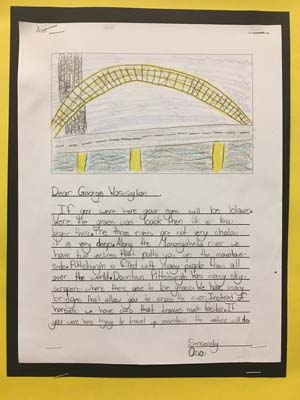

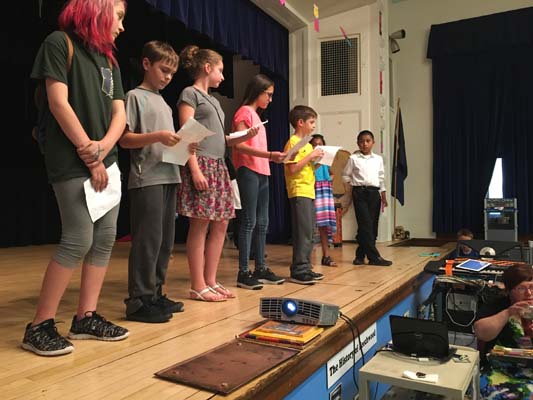

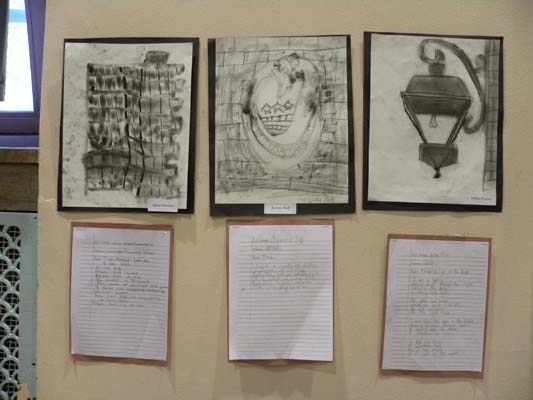

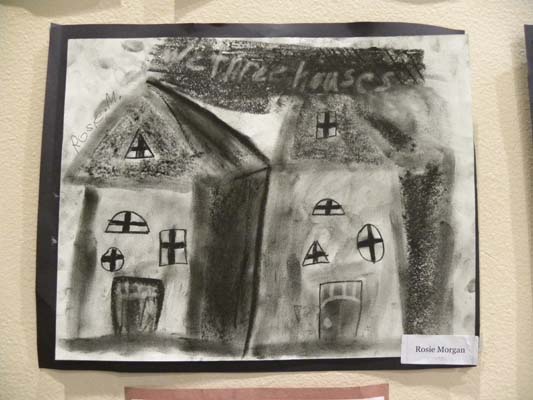

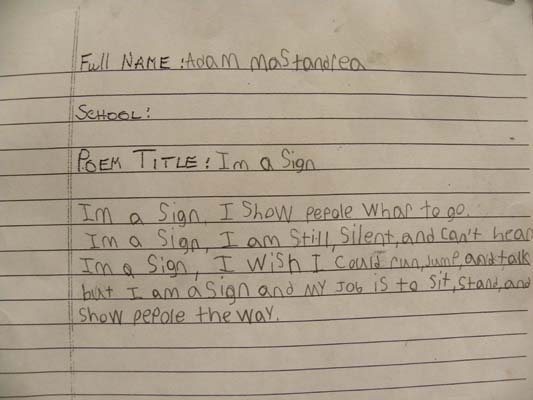

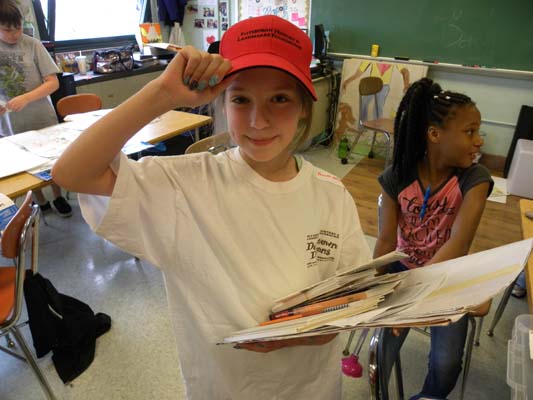

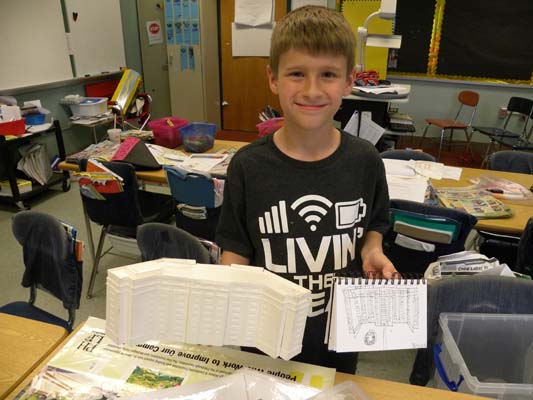

School-wide Celebrations Feature Student Work Accomplished Through PHLF’s “Building Pride/Building Character” EITC Program

Thanks to contributions from nine corporate sponsors and two foundations in 2016-17, PHLF was able to involve students in grades three through eight from ten Pittsburgh Public Schools in a variety of field trips, art activities, and in-school programs from January 13 through June 8.

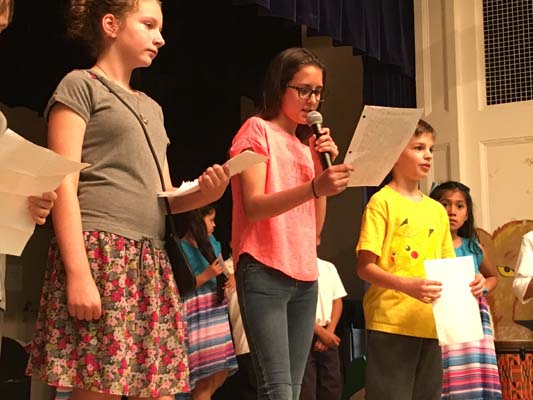

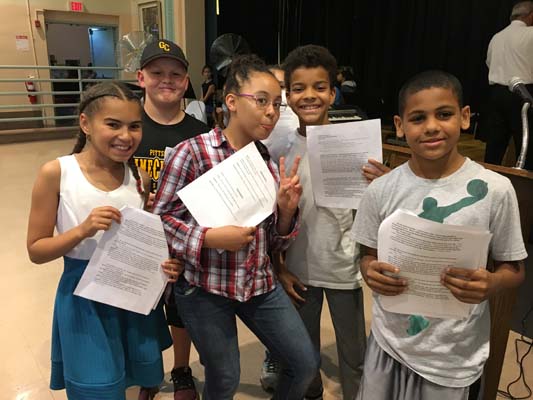

Thanks to contributions from nine corporate sponsors and two foundations in 2016-17, PHLF was able to involve students in grades three through eight from ten Pittsburgh Public Schools in a variety of field trips, art activities, and in-school programs from January 13 through June 8.On May 25, during school-wide celebrations for families, fifth-grade students from Pittsburgh Beechwood and Pittsburgh Whittier read essays they had written describing why their school was worthy of a Historic Landmark Plaque. These essays had, in fact, confirmed earlier recommendations by PHLF’s Historic Plaque Designation Committee to award plaques to each school. After the students read their essays in auditoriums packed with family members, they presented the plaques to their principals. Valerie Lucas, principal of Pittsburgh Whittier, and Sally Rifugiato, principal of Pittsburgh Beechwood, were thrilled.

PHLF’s Executive Director, Louise Sturgess, attended both celebrations and emphasized that the plaques do not place any restrictions on the Pittsburgh Public Schools. Rather, the goal of PHLF’s Historic Landmark plaque program is to recognize places of architectural significance, identify the architect and design/construction dates, and foster a preservation ethic among the people who use the landmark.

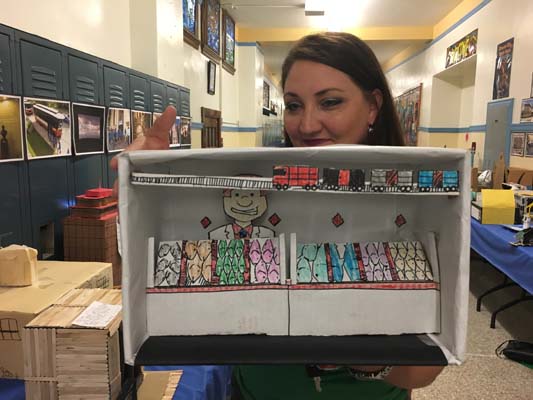

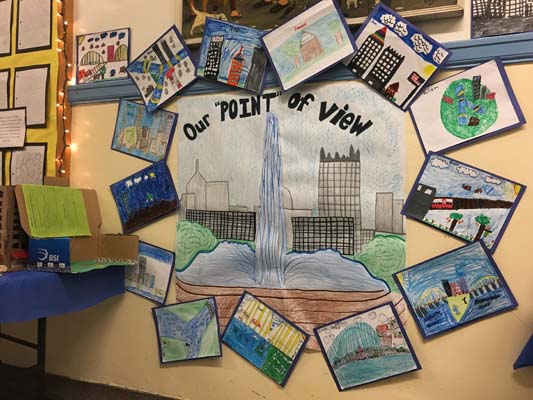

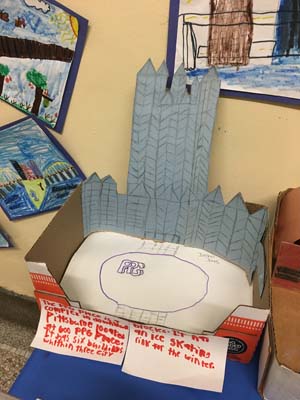

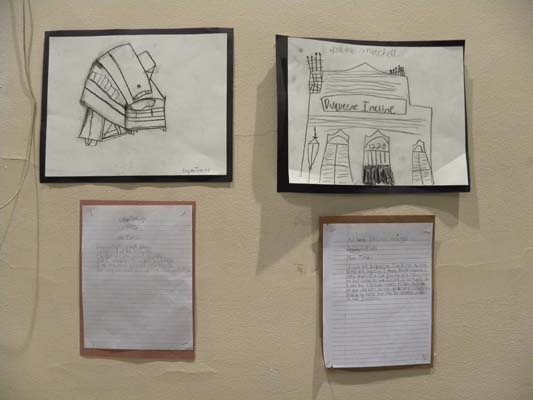

The evening celebrations at Pittsburgh Beechwood and Pittsburgh Whittier also showcased poems, artwork, and three-dimensional models of Pittsburgh landmarks that students had created during PHLF”s “Building Pride/Building Character” program. See photos in the gallery below.

Through tours, art activities, and in-school programs created for the “Building Pride/Building Character” program, students learn about the places and elements that give character to their city––and the more they learn about Pittsburgh, the more “connected” and proud they feel.

As students explore, observe, discuss, and create, they realize that their city is a work in progress. There is always something new being constructed, or something old of value being restored or reused.

They begin to understand that they are works in progress, too. They are growing up and growing older, just as our city is. The older students become, the more “character” they develop. Character is who you are––and who other people think you are. And people, just like cities, are most fascinating when they are full of character-defining traits.

Through “Building Pride/Building Character,” students discover a lot about their school, neighborhood, and city––and a lot about themselves––and fulfill academic standards in the process.

-

June 20 Reception for Landmarks Scholarship Winners and Former Recipients

The Landmarks Scholarship Committee, chaired by PHLF Trustee David Brashear, will welcome four new scholarship recipients and four new honorable mention recipients during a reception on Tuesday, June 20, from 5:00 to 7:00 P.M. on Mt. Washington.

“Our former scholarship and honorable mention recipients are invited to join us on June 20 to help us welcome our 2017 award recipients and their parents,” said Mr. Brashear. “This event is always a wonderful opportunity for us to connect with a group of young people who have achieved academic excellence and possess the potential to make a difference in the Pittsburgh community and beyond. The students we select already feel connected to the city and its history and will hopefully continue to serve the region as leaders in promoting PHLF’s values.”

The four scholarship recipients in 2017 are:

- Eleanor A. Newman, from Barack Obama Academy of International Studies, who will be attending Harvard College and studying Government.

- Brett Monae Searcy, from Barack Obama Academy of International Studies, who will be attending Geneva College and studying Electrical Engineering.

- James J. Shaver, from Pittsburgh Central Catholic, who will be attending the University of Michigan and studying Biology and Biomedical Engineering.

- Liza B. Wilson, from Oakland Catholic High School, who will be attending American University in Washington, D.C, and studying International Business.

Each scholarship recipient will receive a $6,000 scholarship (for book and tuition expenses only), payable over a four-year period to his/her college/university if certain requirements are met.

Because the Scholarship Committee received a record-breaking 81 applications this spring and found so many of the candidates to be excellent, the committee also awarded four Honorable Mentions––a one-time award of $250––to the following people:

- Cassondra D. Hanna, from Gateway High School, who will be attending Fisk University and studying History & Sociology.

- Sarah T. Losco, from North Allegheny Senior High School, who will be attending Penn State University and studying English & Secondary Education.

- Breanna M. McCann, from South Fayette High School, who will be attending Robert Morris University and studying Political Science & History.

- Jiatian Qu, from North Allegheny Senior High School, who will be attending Rice University and studying Psychology while pursuing a pre-med track.

Generous Gifts Continue to Make the Landmarks Scholarship Program Possible

PHLF’s Scholarship Program is funded by generous contributions from the Brashear Family Named Fund and by donations to the Landmarks Scholarship Fund, including contributions to the 2008 and 2014 Scholarship Celebrations. To contribute, visit: www.phlf.org or contact Mary Lu Denny at PHLF (marylu@phlf.org; 412-471-5808, ext. 527).The Landmarks Scholarship Program is the culmination of PHLF’s educational programs for thousands of students from grades PreK-12 and the beginning of its programs for adults. It gives Allegheny County students an incentive to excel in school, become involved in their communities, and express their commitment to this region in a meaningful way. Since the program’s inception in 1999, sixty-eight scholarships have been awarded to high-achieving students in Allegheny County. Thirty-one of those winners graduated from Pittsburgh Public Schools and 37 graduated from other schools within Allegheny County. Eight honorable mention awards have been made since 2016, when that award category was added.

The Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation Scholarship is offered each year. Applications for the 2017-18 school year will be available in January 2018. Applicants must:

- live in and attend school in Allegheny County;

- be a high school senior who has been accepted to a college or university;

- have a cumulative GPA at the end of the first semester senior year of 3.25 or greater;

- have a significant interest in local history, architecture, and/or landscape design; and

- write an essay describing a place in Allegheny County that is important to him/her, complete an application, and submit two letters of recommendation (one must be from a community representative).

-

Fifth-Grade Students Win Historic Landmark Plaque for Whittier School

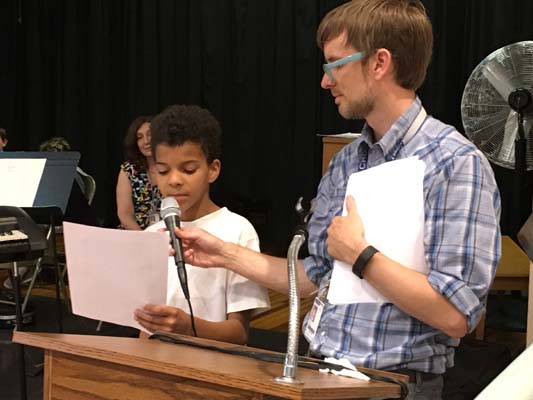

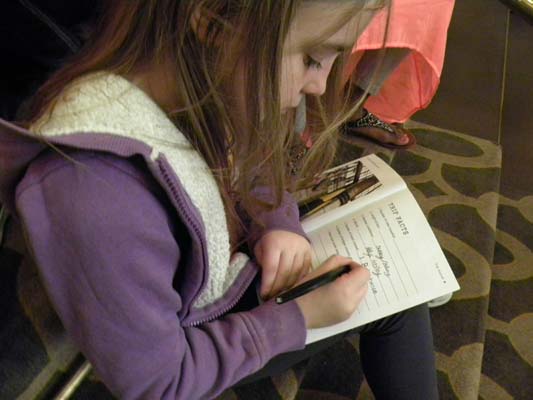

Fifth-grade students read essays to PHLF representatives on April 26 describing what Whittier School meant to them and noting the architectural significance of the school, designed in 1939 by M. M. Steen.

After hearing their essays, David Vater, vice-chair of PHLF’s Historic Plaque Designation Committee, said that the students had indeed presented evidence that confirms the committee’s recommendation. As a result of their good work, fifth-grade students will present the Historic Landmark plaque to their principal on May 25, during Whittier’s Arts and Science Night.

“I loved seeing and hearing the students’ reaction to the news that they would receive the plaque,” said Karen Cahall, PHLF education coordinator. “The tears of joy and relief were touching and showed how much of themselves the students had put into their essays. I was impressed with their presentation skills, with their essays, and with how many of the students came up to shake our hands to say thank you. This was a memorable experience––and we look forward to May 25 with much anticipation.”

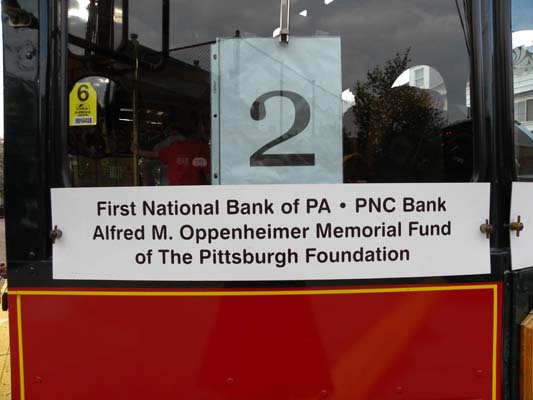

This program is one of many educational initiatives with the Pittsburgh Public Schools, made possible through PHLF’s “Building Pride/Building Character” program that is funded by corporate contributions through the State’s Educational Improvement Tax Credit Program and by grants from the McSwigan Family Foundation and Alfred M. Oppenheimer Memorial Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation.

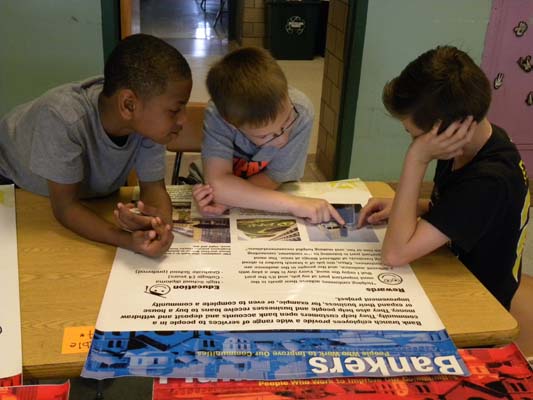

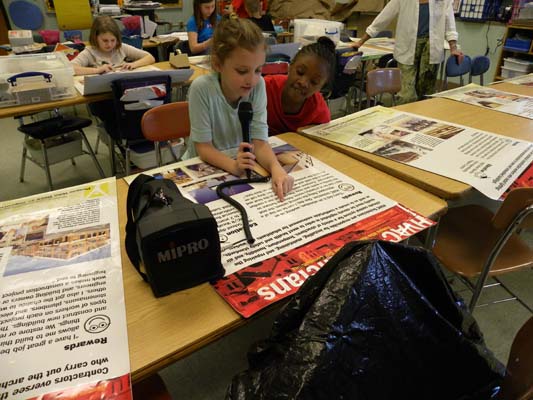

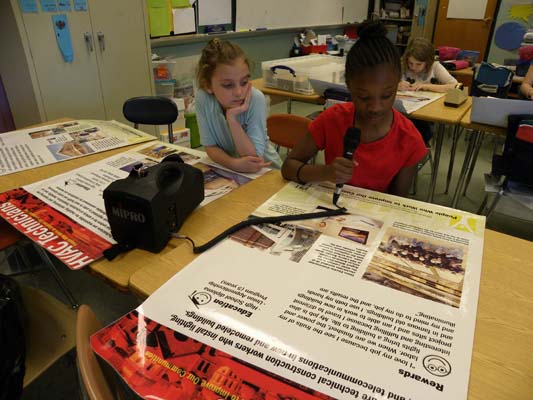

Also through PHLF’s “Building Pride/Building Character” program, fourth-grade students from Pittsburgh West Liberty and Pittsburgh Banksville recently participated in our Career Awareness program, and third-grade students from eight Pittsburgh Public Schools will learn the story of Pittsburgh during trolley tours to five historic sites in Pittsburgh in May and June.

See below, a gallery of photos of the trolley tour on April 20 and of the Career Awareness program on April 26 with Pittsburgh Public School students.

-

Help Preserve a Modern Masterpiece

PHLF members and friends are invited to attend a special event to benefit the preservation of the Frank House in Shadyside, designed in 1939-40 by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. Photo by Ezra Stoller, courtesy of Alan I W Frank.

Join the Art Deco Society of Washington during the 14th World Congress and Alan I W Frank, president and chief historian of the Alan I W Frank House Foundation, on Monday, May 22, for a dinner to benefit the preservation of the Frank House, designed in 1939-40 by Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer.

The open bar reception, beginning at 5:00 p.m., and the dinner at 6:30 p.m., will be held in the Crystal Room of St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Cathedral at 419 South Dithridge Street, in Pittsburgh’s Oakland neighborhood. Guests will enjoy a screening of a new presentation on the Frank House by leading architectural historian Barry Bergdoll, followed by a discussion with Alan I W Frank.

- RSVP and secure tickets by May 17: $140 per guest

- Register at: ly/FrankHouseMay22 or for information: congress@adsw.org

- Inquire about a unique opportunity to tour the ground floor of the Frank House.

The Alan I W Frank House (1939-40) is a work of art brought to life by the most esteemed and influential design visionaries of the 20th-century, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and Marcel Breuer. It remains an unparalleled modern masterpiece and a distinct expression of Pittsburgh’s vital relationship to architecture and innovation.

With the house, interiors, furnishings, and landscape original and virtually unchanged, the mission of the Alan I W Frank House Foundation is to preserve and program this site of modern heritage, providing future access to an international community of art, design, and architecture professionals and enthusiasts, thereby enhancing our community with an exceptional cultural resource. The Alan I W Frank House Foundation, a 501(c)(3) public charity, welcomes direct donations year-round: www.thefrankhouse.org

-

Visit Photo Antiquities on the North Side to See “The Abraham Lincoln Photographic Exhibition”

- Open: Mondays, Wednesdays through Saturdays.

- Hours: 10 a.m. – 4 p.m.

- Ground floor access ADA compliant

- For information: 412-231-7881; bruce817@yahoo.com

PHLF docents and staff toured the Photo Antiquities Museum of Photographic History at 531 East Ohio Street on Pittsburgh’s North Side on April 3. They were fascinated to see how the museum, that began 21 years ago with one display case, has grown to fill five rooms in two historic buildings.

The Lincoln exhibit, opening on May 1, is the largest display of vintage original photographs ever shown under one roof. The exhibit will be on display for one year and will have historical Lincoln photos and artifacts rotating in and out.

Visitors to the exhibit will see:

- The last check Abraham Lincoln wrote before attending Ford’s Theater

- A large oil painting by A. F. King of Lincoln, based on a Mathew Brady photograph

- A quarter-plate Daguerreotype copy of Alexander Hesler’s 1860 portrait

- Vintage photographs by N. H. Shepherd, W. J. Thompson, M. B. Brady, A. Hesler, C. S. German, A. Gardner, and H. F. Warren

- Documents and a portrait by Mathew B. Brady, signed by Lincoln

- A bronze bust of Lincoln in 1860, by Volk, mounted onto a pedestal base

- A plaster Life Mask by Clark Mills

- A copy of a Philadelphia Derringer

- A replica of the Ford’s Theater chair

- An original copy of the Dedication Gettysburg National Cemetery book, c.1864, which contains the first printing of the Gettysburg Address

- Various period prints of Lincoln

- A wax life-like portrait head of Lincoln, by Ivo Zini, c.1980

-

Architecture Feature: Grosvenor Atterbury’s Pittsburgh Buildings

A postcard of the former Federal Street Bridge, which preceded the present-day Sixth Street/Roberto Clemente Bridge, with a view of the four Pittsburgh buildings by Grosvenor Atterbury. Only the Fulton Building (just left of the bridge), now the Renaissance Pittsburgh Hotel, remains.

By Albert M. Tannler

Grosvenor Atterbury (1869-1956) designed buildings of unusual diversity and character.[1] We will explore his career and the four buildings he created for Pittsburgh between 1904 and 1908.

Atterbury was born in Detroit, Michigan. His father was a lawyer, and Atterbury spent summers on Long Island, New York, where his family had a house. He attended Yale University, graduating in 1891. After six months traveling in Europe and Egypt, he enrolled in Columbia University where he studied architecture for two years. During this period he worked in the office of McKim, Mead & White (Stanford White was a family friend) and studied painting during the summer with William Merritt Chase. In 1894 he began a two-year course of study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. When he returned to New York in 1896, he established his own architectural practice, and moved into the family house on Long Island. He began his career designing townhouses, country houses, and cultural and social facilities such as the Parrish Art Museum and the Southhampton Club near his home.[2]

Atterbury’s residential architecture primarily reflected asymmetrical Shingle Style influences and often found inspiration in the picturesque buildings of Britain and Central and Southern Europe.[3]

Atterbury’s Pittsburgh buildings were erected rapidly—in part simultaneously—within a four-year-period, and stood shoulder-to-shoulder along the Allegheny River.[4]

Bessemer and Fulton Buildings

The Bessemer Building was erected 1904-05 at 100 Sixth Street. It was a popular landmark—many postcards survive and photographs were published of both the exterior and the interior.[5] At 13 stories, the stone and brick clad, steel-frame building was a typical office “skyscraper” of the time. Rough-cut Stony Creek granite covered the first-three floors of the facade. The stone base, decorative “quoins” (bands of masonry) around each corner, and the bracketed, wide-eaved, shallow hipped roof pavilions recall Italian Renaissance palaces. The lobby was marble-clad, with polychromatic geometric tile trim and steel grillwork ornamented with an innovative fusion of Renaissance pattern and exposed rivets and bolts. Atterbury displayed two drawings of the Bessemer Building in the 1905 Pittsburgh Architectural Club (PAC) exhibition.

The building was demolished in 1964; a parking garage now occupies the site. The Bessemer and the Fulton Building, erected across Sixth Street, were clearly intended to complement each other. As PHLF’s architectural historian James Van Trump observed in 1967: “It is a great pity that the Bessemer Building was demolished because the two structures together formed a monumental entrance, a kind of triumphal arch at the river entrance to Sixth Street.”[6]

By October 1905 the Fulton Building was rapidly rising at 107 Sixth Street. Completed in early 1906, the Fulton is the larger building. “A steel frame building with an envelope of brick and granite,” Van Trump wrote, “it has … a skylighted interior court that serves as a lobby. This great court with its monumental staircase and galleries is unusually spacious … and gave rise to a legend that the structure had originally been constructed as a hotel.”[7] Light enters the lobby through the great art glass skylight lit by a central light court, facing the river and dramatically exposed to view, and even more dramatically framed by a seven-story arch.

Van Trump refers to a letter Atterbury wrote in 1909 denying that the Fulton had been designed as a hotel (both the recipient and the whereabouts of the letter are currently unknown).[8] Ironically, if prophetically, the Fulton Building now houses the Renaissance Pittsburgh Hotel.

Manufacturer’s Building and the Natatorium

The Manufacturer’s Building was located at 530 Duquesne Way (now Fort Duquesne Boulevard).[9] Construction began September 14, 1906, and the 16-story building was completed in 1907. Elevation drawings were displayed at the 1907 PAC exhibition and photographs and postcards exist, but less is known about this building than any of the others. It was the tallest member of the ensemble. Although it shared their granite base, the Manufacturer’s Building had a ten-story shaft of great simplicity topped by a three-story penthouse—an architectural Easter bonnet displaying classical forms—gables with balustrades, fan and circular windows, symmetrical rough-cut stone trim. The Manufacturer’s Building was not an office building, like the Bessemer or Fulton buildings, but a loft building, offering tenants high ceilings and unobstructed floor space.[10] The building was demolished in 1956 and a parking garage now occupies the site.

The Pittsburgh or Phipps Natatorium, a bathhouse and swimming pool, was soon erected at 540 Duquesne Way, behind the Manufacturer’s Building, and could be entered through it. The building was designed and built 1907-08; Atterbury displayed three views of the swimming pool at the 1907 exhibition. In 1980, Van Trump wrote about Pittsburgh bathhouses in Pittsburgher Magazine, observing:

Even more stylish—truly a bathing establishment of Roman Splendor—was the Natatorium, a structure of almost imperial dimensions. The four-story structure was located on Duquesne Way near the Sixth Street Bridge. This was a commercial rather than a charitable venture. Anyone who had 25 cents could get a tub bath, but the place was chiefly famous as possessing the first great swimming pool in Pittsburgh.[11]

The swimming pool was clad in Guastavino tile, a light-weight, fire-proof acoustical tile used in churches, railroad stations, public buildings, and occasionally private homes. Four detailed drawings for the pool have been preserved in the Guastavino Company Archives at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.[12] The Natatorium was demolished in 1935 to reduce property taxes and the site remained vacant for some years.

Atterbury after Pittsburgh

Atterbury last displayed his work in Pittsburgh at the 1910 PAC exhibition—houses he had designed years before at Bayberry Point, Long Island. He continued to design country estates on Long Island; he redecorated major rooms in New York City Hall, and he designed the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1924-25). He designed hospitals and medical facilities, including the Yale University Medical Library, and educational buildings and clubhouses.

He also continued to design worker housing in New York City, and experimented with prefabricated reinforced concrete to produce standardized, low-cost housing. He became an urban planner/designer, first and most notably at Forest Hills Gardens in Queens (1909-13), where he and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. created a 140-acre planned community 15 minutes from Manhattan by train. Atterbury designed Indian Hill Village for the Norton Company in Worchester, Mass. (1915-16), as well as worker housing in Cincinnati, Mocanaqua, Pa. (Luzerne County), and Erwin and Kingsport, Tennessee.[13]

By all accounts, Atterbury had a successful career. His idealistic commitment to affordable housing may have been uncommon, but his exploration of innovative technologies while creatively re-imagining traditional forms was typical of peers such as Burnham, Hornbostel, and Post, as recent studies have shown.[14] Still, as biographer David Dwyer notes: “It was as a town planner with a special concern for housing the poor and for hospitals that he wished to be known. Architects with such interests rarely become famous.”[15]

[1]The first critical study of Atterbury was published in 2008: Peter Pennover, and Anne Walker, The Architecture of Grosvenor Atterbury (New York: W. W. Norton, 2008).

[2] Donald Dwyer, “Grosvenor Atterbury, 1869-1956.” Long Island Country Houses and Their Architects, 1860-1940, ed. by Robert B. MacKay, Anthony Baker, and Carol A. Taynor (New York: W. W. Norton, 1997), 49-57. Also “Biographical Sketch” (May 22, 1953), Grosvenor Atterbury papers, Rare and Manuscript Collections, Carl K. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

[3] For illustrations of his work, in addition to Long Island Country Houses cited above and Pittsburgh Architectural Club exhibition catalogs cited below see American Architect and Building News 94 (August 26, 1908) and (September 2, 1908) and C. Matlack Price, “The Development of a National Architecture: The Work of Grosvenor Atterbury.” Arts and Decoration 2:5 (March 1912): 176-179.

[4] James D. Van Trump, “Henry Phipps and the Phipps Conservatory,” Carnegie Magazine 50:1 (January 1976), 31, had credited Atterbury, who designed the Phipps Houses in New York in 1905 (and later), with the design of the demolished Phipps Model Tenement erected in Allegheny 1906-08. The building was designed by Alfred C. Bossom (1881-1965) and the drawings were executed in Atterbury’s office.

[5] The Brickbuilder 13 (June 1904), 131; 14 (October 1905), 236; “Bessemer Building interior, Grosvenor Atterbury,” Ohio Architect & Builder 14:6 (December 1909): 42.

[6] James D. Van Trump and Arthur P. Ziegler, Jr., Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 1966): 53.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Fulton Building,” James D. Van Trump Notecards, Van Trump Papers, James D. Van Trump Library, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

[9] Construction 3:3 (January 20, 1906): “Henry Phipps has approved the plans for a fourteen-story building on his Duquesne Way property in the rear of the Bessemer Building. The plans were drawn by a New York architect. It is expected that work will be started by April 1st. The plot has a frontage of 120 feet on Duquesne Way. The new building will be on the site of the present natatorium building and it is said that another natatorium will be constructed in the rear of the fourteen-story building. The big building will be used for storage and light manufacturing purposes.” [53]

[10] “Downtown Landmark Soon to Be Torn Down,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 29 February 1956.

[11] James Van Trump, “Jamie’s Journal: The Great Unwashed,” Pittsburgher Magazine (October 1980), 19-20. See also “The Pittsburgh Natatorium, Pittsburgh, PA,” The Builder 27:7 (October 1909), 40; 1 unnumbered plate.

[12] “Phipps Natatorium,” Janet Parks and Allen G. Neumann, The Old World Builds the New: The Guastavino Company and the Technology of the Catalan Vault 1885-1962 (Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, 1996), 93.

[13] G. Atterbury, “Model Towns in America,” Scribner’s Magazine 52:1 (July 1912), 20-35; Samuel Howe, “A Forerunner of the Future Suburb: The Growing Popular Appreciation of the Picturesque in Domestic Architecture,” Arts and Decoration 2:12 (October 1912), 414, 419-422; Susan L. Klaus, A Modern Arcadia: Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and the Plan for Forest Hills Gardens (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press), 2002; Laurence Veiller, “Industrial housing developments in America. Part IV: A Colony in the Blue Ridge Mountains at Erwin Tenn.: Grosvenor Atterbury, Architect and Town Planner,” Architectural Record 53:6 (June 1918), 547-559; Margaret Crawford, Building the Workingman’s Paradise: The Design of the American Company Town (New York: Verso, 1995, chap. 6). John L. Fox, Housing for the Working Classes: Henry Phipps from the Carnegie Steel Company to Phipps Houses (Larchmont, NY, 2007).

[14] In addition to Schaffer, Daniel H. Burnham (2003), see Sarah Bradford Landau, George P. Post, Architect (New York: Monacelli Press, 1998) and Walter C. Kidney, Henry Hornbostel: An Architect’s Master Touch (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 2002).

[15] Dwyer, “Grosvenor Atterbury,” 57.