Category Archive: PHLF News

-

Register for the “Greene County Heritage Workshop: Practical Ways to Care for Your Historic Building(s)”

Saturday November 4, 2017

9:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m.

Free (including a boxed lunch)Location: Margaret Bell Miller Middle School, 126 East Lincoln Street, Waynesburg, PA 15370

Reservations required by October 31: marylu@phlf.org; 412-471-5808, ext. 527

More than 65 members and foundations contributed to PHLF’s 50th Anniversary Fund between 2014 and 2017. One of the goals of that fundraising effort was to help PHLF provide technical assistance to main streets and historic neighborhoods throughout the Pittsburgh region, with a particular emphasis on outlying counties where no local preservation organizations exist to assist concerned citizens.

After much planning and with the local support of 17 co-sponsoring organizations in Greene County, PHLF is pleased to announce that it will host the first of several Heritage Workshops serving outlying counties on Saturday, November 4, at the Margaret Bell Miller Middle School in Greene County, PA.

Click here for an agenda of speakers and topics. Although the workshop is intended for Greene County residents, anyone interested in preserving historic buildings is invited to attend.

“Many people misunderstand how historic properties fit into a dynamic 21st-century economic environment,” said Bill Callahan, Western PA Community Preservation Coordinator of the Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office, Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. “This workshop will look beyond limited public funding to explore how a community’s historic character fits into economic development strategies. It will outline best-practice approaches to preserve, promote, and invest in historic community character,” he added.

Mary Beth Pastorius, a trustee of PHLF and a native of Greene County, has been instrumental in planning the conference. “PHLF is sharing its expertise in ‘Renewing Communities and Building Pride’ with rural areas outside Allegheny County that have many historic assets but little experience in ‘how to’ preserve,” she said. “I encourage anyone who cares about saving the unique character of Greene County to attend this workshop. It’s been specifically tailored to meet their needs and interests.”

-

Thank You, Interns

“It was a terrific help to have five undergraduate and graduate students assisting us with our educational and archival activities this summer,” said Executive Director Louise Sturgess. As a result of their help, we launched a Facebook Group for all Landmarks Scholarship recipients, completed several archival projects, selected a location and prepared materials for our 21st annual Architectural Design Challenge, began planning for a Heritage Workshop in Greene County on November 4, and offered many educational programs for people of all ages.

We thank the following students for volunteering their time and talents to PHLF this summer:

- James Barnett, from Bruceton Mills, WV, who is studying Public Policy, Urban Affairs, and Business at the University of Delaware;

- Morgan Collins, from Pittsburgh, who is studying Strategic Communications at Elon University in North Carolina;

- Ilana Kisilinsky, from Pittsburgh, who is studying Media Studies at Yeshiva University in New York City;

- Lauren Stanley, from Belle Vernon, who is a graduate student in Duquesne University’s Public History program; and

- Tess Wilson, from Pittsburgh, who is completing her Master’s in Library & Information Sciences at the University of Pittsburgh.

The interns summed up their summer experiences with the following comments:

“This summer really immersed me in valuable field work that has to do with my major and career path. I learned so much by working with the community members and historic buildings in Greene County––both crucial parts of Public Policy and Urban Planning. I enjoyed every second of it and hope the preservation workshop on November 4th goes well!” ––James Barnett

“As a strategic communications major, I expected to be writing copy and editing photos for most of my time at PHLF. Instead, I helped with tours nearly every day of my internship. Watching groups of children, high schoolers, adults, and senior citizens react with the same awe to Pittsburgh’s architecture and its history reaffirmed my appreciation for the city I call home.” ––Morgan Collins

“PHLF taught me to open my eyes, to really look and see, not just buildings but works of art. There are so many beautiful details that make up our city and now I will look for every one.” ––Ilana Kisilinksy

“I enjoyed my summer at PHLF tremendously. I learned so much about Pittsburgh from its incorporation to present day. Best summer internship.” ––Lauren Stanley

“As a youth librarian and educator, I especially enjoyed experiencing the unique ways in which PHLF programming allows kids to engage with their city. Even a single Downtown Dragons Tour can make an extraordinary impact on our young citizens, and that knowledge serves as a daily reminder of why I do what I do.” ––Tess Wilson

-

Mary E. Tillinghast and Urania, The Muse of Astronomy

By Albert Tannler

In 1882, Western University of Pennsylvania (which became the University of Pittsburgh in 1904) moved to Allegheny City. In 1894 land was purchased at the summit of Riverview Park for a new observatory.[1] The cornerstone of the Observatory was laid on October 20, 1900 and construction began.

La Farge created his Fortune window 1900-1902; it was installed in the Frick Building for the building opening on March 15, 1902.

The Observatory is a scientific acropolis—a tan brick and white terra cotta hill-top temple whose Classical forms and decoration symbolize the unity of art and science. The L-shaped building consists of a library, lecture hall, classrooms, laboratories, offices, and three hemispherical domed telescope enclosures. Two were reserved for research; one for use by schools and the general public. The core of the building is a small rotunda, housing an opalescent glass window depicting the Greek muse of astronomy, Urania.

Director Frank L. O. Wadsworth, of the observatory of the Western University of Pennsylvania, announced last evening the arrival of a stained glass window from New York as the gift of the Misses Smith, who have devoted a generous sum to the establishment of the observatory. Prof. Wadsworth says the window is to adorn the new structure of the observatory. It is pronounced one of the most artistic works of Miss Mary E. Tillinghast.

The window, which is 9×3 feet, shows Urania, almost lifelike, standing in an open porch. Her garb is of the ancient Grecian fashion; in one hand she holds a planet, the other being raised to the heavens. Beside her resting against a pedestal is a pair of compasses; on the pedestal is the lamp of knowledge, whose flames lighten the figure. She stands between two columns. Around one is a wreath of laurel.

Far behind her, in the moonlight, are the ruins of the Acropolis. Shining in the sky and placed relatively with astronomical precision are the moon, the evening star, planets of Pleiades. Under the figure is a delicately blended spectrum, typifying the work of the observatory.

This thorough description of the window in the Observatory appeared in the Pittsburgh Post on July 3, 1903.[2] The donors were a pair of well-to-do philanthropic siblings, Jennie Smith (1832-1911) and her younger sister, Matilda (1837-1909). When the University moved to Allegheny City, the Smith sisters became enthusiastic supporters. John Brashear remembered them as:

two good women that lived on the avenue just beyond the Observatory, who from the very beginning of the work of the new institution, contributed liberally, not only of their means, but gave their personal interest to many of the details of architecture, ornamentation, and other things. A beautiful window on the northern side of the building, the Riefler precision clock, the beautiful marble finish of the main building, and many other such matters were due to their interest and generosity.[3]

The artist was Mary Elizabeth Tillinghast (1845-1912) of New York City.[4] Like many American artists of the period, she spent several years in Europe, visiting Italy and studying painting in Paris. One of her teachers, Emile-Auguste Carolus-Duran, also taught the most famous American painter of the era, John Singer Sargent.

In 1878 Tillinghast began a seven-year affiliation with New York artist John La Farge (1835-1910)—painter, muralist, critic, and inventor of a new process for making decorative glass windows. Tillinghast became an expert textile designer, served as manager of the La Farge Decorative Art Company, and learned the art of designing and making windows from La Farge.

In 1878 Mary Tillinghast began a seven-year affiliation with New York artist John La Farge (1835-1910)—painter, muralist, critic, and inventor of a new process for making decorative glass windows. Tillinghast became an expert textile designer, served as manager of the La Farge Decorative Art Company, and learned the art of designing and making windows from La Farge. Urania was installed in the Observatory on July 3, 1903.

La Farge patented his “opalescent” window glass in 1880: “The object of my invention is to obtain opalescent and iridescent effects in glass windows . . . softening the light, and, by reason of its unevenness of structure and formation [prevent] the direct passage of rays of light.”[5] This new glass was known at the time as “American Glass.” Historian Barbara Weinberg notes that La Farge developed it in order to “reconcile the color and brilliance of early glass with contemporary desires for naturalistic form . . . , to permit depiction of rounded forms and convincing space.”[6] American Renaissance painters admired the three-dimensional realism introduced by Raphael and 15th-century Renaissance painters, and sought to emulate it—in paintings and in glass windows.

Tillinghast’s first major window, Jacob’s Dream, was installed in 1887 in Grace Episcopal Church, New York City. She worked from her Greenwich Village studio, primarily as a window designer, but she also designed furniture and, in one case, was architect, decorator, and glass artist for a private chapel. Her glass was exhibited and won gold medals at several World’s Fairs. In addition to church windows, she designed windows for residences, and for institutions, most notably Urania in Pittsburgh and The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1908) in the New York Historical Society.

Tillinghast and La Farge each designed a window in Downtown Pittsburgh.[7] La Farge’s Fortune in the Frick Building, designed by American Renaissance architect and planner D. H. Burnham of Chicago, was installed in 1902; Tillinghast’s Urania was installed in 1903. Each window portrays female figures framed by Classical columns—art echoing the architectural character of the building.

[1] The history of the Allegheny Observatory is taken from John A. Brashear, John A. Brashear: The Autobiography of A Man who Loved the Stars, Ed. by W. Lucien Scaife (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1924).

[2] “Window for Western Observatory,” Pittsburgh Post, 3 July 1903, 1. See also “Artistic window presented to Allegheny Observatory by the Misses Smith of Allegheny—Put in place within the week,” The Bulletin 47:10 (June 27, 1903), 1, 14.

[3] Brashear, Autobiography, 141-142. See also Ruth McCartin, “The Smith Sisters of Old Allegheny,” The Allegheny City Society Reporter Dispatch 1:3 (1996): 6-7, 9-10; and “Miss Matilda Smith, Philanthropist, Dies,” Pittsburgh Gazette, 1 November 1909.

[4] Gilson Willets, “Mary E. Tillinghast,” The Art Interchange 31:6 (December 1893),146-149; “Woman Stained Glass Artist: Mary Tillinghast’s Work in Pittsburgh and Other Cities.” Pittsburgh Post, 15 July 1906; New York Times, 16 December 1912: 13; Betty MacDowell, American Woman Stained Glass Artists, 1870s to 1930s: Their World and Their Windows (Diss. Michigan State University, 1986), 254-256, 326; L. A. Richards, “An Unworthy Obscurity,” Stained Glass 89:1 (Spring 1994), 35-41, 51-52.

[5] H. Barbara Weinberg, “John La Farge and the Invention of American Opalescent Windows,” Stained Glass 67:3 (Autumn 1972), 6.

[6] H. Barbara Weinberg, “The Early Stained Glass Work of John La Farge (1835-1910),” Stained Glass 67:2 (Summer 1972), 10.

[7] La Farge also designed three windows for the Presbyterian Church, Sewickley: Victory of Easter, c. 1897; Contemplative Angel, c. 1899; and Prayer and Hope, c. 1908.

-

Architecture Feature: B. F. Jones Memorial Library, Aliquippa, Pa.

“Classic Lines, Sufficiently Modern, a Charming Freshness, and Dignity of Style”: B. F. Jones Memorial Library, Aliquippa, Pa.

By Albert Tannler

Adhering strikingly to the classic lines of the Renaissance, The B. F. Jones Memorial Library is nevertheless sufficiently modern in its treatment to suggest a charming freshness which in no way detracts from its dignity of style.— Programme of the Presentation and Dedication of B. F. Jones Memorial Library. Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, February 1, 1929

Angelique Bamberg notes:

The present City of Aliquippa was created from the merger of the towns of Woodlawn and Aliquippa in 1928. . . . The city’s history is closely tied to that of the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad (P&LERR) and the Jones & Laughlin Steel Company. The P&LERR’s line from Pittsburgh to Youngstown, OH was completed in 1879. To encourage passenger traffic from both cities, the railroad opened an amusement park, Aliquippa Park, roughly equidistant between them in 1880. The name Aliquippa was chosen by the President of the P&LERR, who had an interest in Native American history; Queen Aliquippa was a leader of the Seneca Tribe in the 18th century. There is no evidence of a direct association between the historical figure of Aliquippa and the town site, however.[1]

The Building and the Donor

According to the National Register Nomination Form, “the library serves as a fitting memorial for one of the industrial giants and cofounders of Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, Benjamin Franklin Jones, Sr. [1824-1903] His contributions, along with those of his family and associates, are part of the history of steel making and the socio-economic impact which resulted from J&L’s growth. His daughter, Mrs. Elisabeth McMasters (Jones) Horne, recognizing the importance of individual development, offered to erect a library more responsive to the needs of the public. Her generous gift to the community has probably had as much effect on the growth and development of the community as did the steel plant several blocks away.”[2]

According to the National Register Nomination Form, “the library serves as a fitting memorial for one of the industrial giants and cofounders of Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, Benjamin Franklin Jones, Sr. [1824-1903] His contributions, along with those of his family and associates, are part of the history of steel making and the socio-economic impact which resulted from J&L’s growth. His daughter, Mrs. Elisabeth McMasters (Jones) Horne, recognizing the importance of individual development, offered to erect a library more responsive to the needs of the public. Her generous gift to the community has probably had as much effect on the growth and development of the community as did the steel plant several blocks away.”[2]The National Register of Historic Places Inventory––Nomination Form of 1974 gives a detailed listing of the elements of the building while noting: “The interior has been little altered although some rooms are no longer used for the purposes for which they were designed.”[3]

The February 1, 1929 Programme of the Presentation and Dedication of B. F. Jones Memorial Library, gives a sense of character of the building:

The library building . . . is remarkable not alone for its architectural beauty. The entire structure reflects the thoroughness with which the project was studied long before erection, in order that the completed building might lend itself in every way to the work and service to be accomplished. Consequently, one finds book stacks, work rooms, rest rooms, a librarians office, an exhibition room, furniture, filing cases and other carefully selected equipment, all so favorable [sic] situated and co-ordinated that the building is practically perfect as to workability. Building materials include “grey Indiana limestone . . . Kasota marble . . . and Travertine from Italy.”

The Architect and the Artists

Brandon Smith was among a handful of the most talented eclectic architects to have practiced in western Pennsylvania. One of the last in a noted generation of traditionalists, his work at Fox Chapel Golf Club, The Edgeworth Club, and on a series of fine residential designs are distinguished by thoughtful accommodation and unfailingly gracious resolution. He is deservedly remembered as Pittsburgh’s most sought after high society architect.

Smith was born in Allegheny City in 1889. His parents were Charles O. and Elizabeth Benn Smith. His family was of German and English descent and his father owned the Sterling White Lead Co., which was later sold to the National Lead Co.

Brandon graduated from the old Central High School, his first job was demonstrating roadsters and early automobiles. He attended architectural classes at Carnegie Tech in the years 1910 – 1912. He was a student of unmistakable talent and sophistication, but he never graduated from the program. He enlisted in the Army in 1917 and served as Lieutenant in the Field Artillery during World War I.

While stationed in Salt Lake, Utah, he met and later married Kate Nelson. They had two daughters, Marian and Barbara.

It’s important to note that early in his career Brandon worked in the office of Alden & Harlow. From 1920 – 1927 Brandon worked in partnership with Paul A. Bartholomew, a University of Pennsylvania graduate who had also worked at Alden & Harlow. Bartholomew & Smith had offices in Pittsburgh and Greensburg.[4]

The years of the Great Depression and the Second World War were very hard on architectural careers and Brandon despaired that the profession would never recover. During the war years some of his beautiful drawings for designs that would never be built were exhibited by the Pittsburgh Architectural Club, and by the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh. He remained a traditionalist, opposed modernist ideas, and retired to Florida in 1955. There he also designed a few buildings, and died in Pensacola in 1962 at the age of 72. He is buried in Arlington Cemetery.[5]

David Vater observes that “the B.F. Jones Memorial Library at 603 Franklin Street in Aliquippa, PA . . . is without question the finest building in this once prosperous steel town. . . . It’s well worth a visit.” The National Register of Historic Places form notes that “Three large 30 light windows are set behind the recessed columns. . . The side elevations each have three windows of 30 lights.” David Vater quotes Smith’s daughter who observed that her father “always insisted upon driving convertibles because he was a claustrophobic, like the bright yellow Nash and a little green MG he used to race about in. Perhaps his claustrophobia was the motive for the generous fenestration and a preoccupation with openness in many of his architectural designs.”[6]

Artwork in the library consists of a larger-than-life bronze and marble statue of B. F. Jones by Robert Aiken of New York City; the color scheme in the building was planned by Norah Thorpe of New York City; Mrs. Horne’s portrait is by Dutch portrait painter Alfred Hoen; and the leaded glass windows are by Henry Hunt of Hunt Studios, Pittsburgh.

Bibliography

Programme of the Presentation and Dedication of B. F. Jones Memorial Library. Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, February 1, 1929.

50th Anniversary, B.F. Jones Memorial Library 1929-1979. Aliquippa, Pennsylvania.

- F. Jones Memorial Library, National Register of Historic Places Inventory––Nomination Form. Placed on the NRHP on December 15, 1974.

Vater, David J. “Brandon Smith, Eclectic Architect.” Fox Chapel Golf Club, October 2, 2005.

Bamberg, Angelique. “An Architectural Inventory, Franklin Avenue Aliquippa, PA. Report of Findings and Recommendations.” Prepared for the Community Development Program of Beaver County in cooperation with Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office by Clio Consulting, June 12, 2016.

[1] Angelique Bamberg, An Architectural Inventory, Franklin Avenue Aliquippa, Pa, 3.

[2] “B. F. Jones Memorial Library,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form, n.p.

[3] Ibid.

[4] David Vater notes that Smith later partnered with Harold O. Rief, with offices in downtown Pittsburgh.

[5] Vater, “Brandon Smith, Eclectic Architect,” 2005.

[6] Ibid.

-

An Essay On Town Planning in Upstate New York

On a recent trip to Upstate New York, Arthur Ziegler, president of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation (PHLF), toured the historic Chautauqua community, Buffalo’s Canalside, a waterfront development on the Erie Canal Harbor in Buffalo, and Niagara Falls. He recounts the trips and some of his thoughts and observations on the history of the area, sense of place, and town planning in the essay below.

By Arthur Ziegler

It had been many years since I last visited the Chautauqua Institution near Jamestown, New York, when I drove up there a couple of weeks ago to take in a performance by Garrison Keillor, the noted author, humorist, and radio personality. The Chautauqua Institution, of course, was embroiled in considerable controversy in recent years concerning its demolition of its historic amphitheater, which had been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. We, at PHLF, joined the preservationist voices from all across the country in opposition to the Institution’s plans, but the board of directors of the Institution won out and raised over $23 million to demolish it and build what is actually a rather good replica.

From what I observed, they have created a better access for physically handicapped patrons, a large addition to the theater for back-of-the-house improvements and space needed for performers. The wooden benches and the spaces, the stage, are all replicated and the organ is in place. One would hardly know the difference but one can feel the loss of the patina of time that one felt in the former amphitheater.

For this opening week Garrison Keillor performed with two cast mates from his old radio variety show, A Prairie Home Companion, and the acoustics in the amphitheater were perfect both for performers and the several thousand attendees who joined in singing old-time songs. A new plaza will be developed in front of the theater in the coming year to make that area more inviting.

It is the planning—or lack of planning—that makes Chautauqua itself so welcoming and really endearing. There is a relative grid pattern of streets except for a curving street from the lakefront up toward the hotel. There are few curbs, few sidewalks, and yards go right to the edge of the asphalt and almost every yard has a front yard garden or little lawn. In late July, the flowers were all in bloom, making the town feel very inviting. The informality of the roads and gardens is rare in America and largely disallowed anywhere in planning today.

The architecture of Chautauqua, largely Gothic, board and batten, and some classical, is an endless treat to the eye and every time one walks for about a block, no matter how often it is repeated, one sees new details. In Chautauqua, it appears, that no house has setback requirements and there is no single-use of land i.e., a street block might have single-family houses, inns, rental cottages, lecture hall, restaurant, art center. Everything exists in harmony, a notion that runs counter to our contemporary ideas of urban planning where different uses are isolated from one another.

What they have in Chautauqua that also helps to make the community feel inviting and in-tune with nature is that shade prevails. The town is filled with great trees everywhere, a mixture of deciduous and conifers. One can walk the entire town with comfort because of its short street blocks. There, I recalled that Jane Jacobs taught us the value of short blocks.

Amidst the charm of the town, I was reminded that the community in Chautauqua was founded as a religious retreat by the Methodist churches and religion still prevails. The residents and visitors are— at least when I was there— almost entirely white, and aging. Occupants of houses now seem to be permitted to have alcoholic beverages on their porches but the great hotel has limited its offerings to wine and beer. While the artistic and intellectual programs are plentiful and varied, Chautauqua still seemed to be limited in its demographic appeal and I wondered how many of the people that were there will be there 10 years from now due to age and infirmity. In the future, I wondered: What will bring younger more diversified people there?

Buffalo

From Chautauqua, I drove farther north along I-90 to Buffalo, New York, to visit and see Canalside, a waterfront redevelopment in an historic district on the city’s inner harbor. Located within Buffalo’s Downtown, the redevelopment of the area started in 2005 when the state of New York formed the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation, a state agency that was charged with planning the redevelopment of this historic site to help boost Buffalo’s economic resurgence.

Stanton Eckstut, a leading preservation planner and architect with Perkins Eastman— and who has done considerable work with our organization over the years— was the project designer and through his vision the Erie Canal has been resurrected, water is flowing, and a Downtown playground has been established all around it with a number of developments scheduled to come.

Stanton Eckstut, a leading preservation planner and architect with Perkins Eastman— and who has done considerable work with our organization over the years— was the project designer and through his vision the Erie Canal has been resurrected, water is flowing, and a Downtown playground has been established all around it with a number of developments scheduled to come.A light rail line comes right to the project connecting to the business area a couple of blocks away. Here is a planning triumph, I thought, in that it is bringing residents and visitors back Downtown and in the winter when the water is frozen in the canal, it is a hugely popular ice skating rink. I saw a group of youngsters enjoying hula hoops, some oldsters talking to one another in a collection of Adirondack chairs, and people enjoying views of the water, the marina, and a great naval destroyer anchored there. A highway soars over the site on concrete posts and it has been retained and people frolic underneath it.

The area has been pedestrianized with easy access by vehicle and parking and various areas are treated in different ways, some with wooden boardwalks, some with lawns, some with blocks that might have been used in the ships that sailed there, old foundations from the canal and adjoining buildings have been excavated, and interpretive panels have been displayed with good graphics narrating the history of the area.

The area has been pedestrianized with easy access by vehicle and parking and various areas are treated in different ways, some with wooden boardwalks, some with lawns, some with blocks that might have been used in the ships that sailed there, old foundations from the canal and adjoining buildings have been excavated, and interpretive panels have been displayed with good graphics narrating the history of the area.I could see that Stan Eckstut and his team sought to renew the core of the city as a major attraction by reviving its history. In doing planning anywhere, Stan first looks to the history of what happened at a particular site and then develops relevant concepts for people living, working, and playing in the space today. In Buffalo, unlike Chautauqua, people of every age and race were there in abundance and the place felt alive.

It also occurred to me that Canalside is very different from our own historic Point State Park in Pittsburgh, which is really disconnected from the rest of Downtown. Here, our history in Point State Park is treated modestly and was recently mostly covered up. It is no wonder that the park is not heavily used unless there is a special event.

At Point State Park, the museum is almost hidden away and the Block House was saved only through the intrepid determination of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The foundations of the historic buildings, historic wharfs, were all eliminated in favor of plain concrete walkways around the rivers’ edges. It is beautiful and pristine but not in any way equivalent to the educational playground I saw at Canalside.

Niagara Falls

About half an hour’s drive north of Buffalo lies the majestic Niagara Falls. On the American side of the falls, we have a Downtown whose street pattern is elusive. Traffic overwhelms the town, parking is not neatly provided. The park and the falls are hidden beyond various tourist stores in the town. Way finding is hard for pedestrian or drivers but when one finally arrives at the park, which is maintained by the National Park Service, the landscaping, unlike at Chautauqua or Canalside, leaves a lot to be desired. It feels more like the remnants of a landscaped park, with shrubs and trees looking like they need nourishment. The lawn in many places is just dirt. Granted that there are many thousands of visitors here and it can be hard to maintain landscaping but it is done across the river in Canada very well.

Signage is poor if it exists at all and one can end up driving around and around the same block or doing the same on foot because each block seems to be lined with the same tourist shops. Niagara Falls is a major world attraction and we should have there a town outstanding for its architecture and its linkages to the river and the Falls and demonstrate our country’s planning and landscaping to the best.

One very good thing that can be said about Niagara Falls is that the population is highly diversified. People from every country, every ethnic background, and every age are there and the great natural wonder of the Falls delivers a spectacle that somehow equalizes the human beings who come to enjoy it and they seem to enjoy one another.

As I reflect on my journey to this part of Upstate New York, I can’t help but wonder:

- How will Chautauqua Institute move toward the future?

- How should Buffalo work to spin off more good economic development for the future by its investment in the visionary Canalside?

- How can Niagara Falls reconfigure itself to be in itself an attraction that befits and enhances the natural attraction that brings people there?

-

Doors Open Pittsburgh: October 7-8, 2017

Doors Open Pittsburgh Features Sites in Downtown, on the North Side, and in the Strip District: October 7 & 8, 2017

The second annual Doors Open Pittsburgh, a nonprofit 501c3, will be presented in partnership with AIA Pittsburgh, Visit Pittsburgh, and PHLF on October 7 & 8, 2017. The event will provide a unique opportunity to explore and experience the interiors of a collection of Pittsburgh’s iconic and newly designed buildings in Downtown Pittsburgh, on the North Side, and in the Strip District. The buildings will be announced on the Doors Open website on August 7.

New to this year’s event are “Insider Tours.” These fully-guided, thematic tour experiences will be a great option for participants yearning to learn more about Pittsburgh’s fascinating architecture. PHLF will offer a “Downtown Safari” walking tour for families on Saturday, October 7. This 90-minute adventure will call attention to the stone, terra cotta, and metal creatures that inhabit Pittsburgh’s historic bridges and buildings. Details for this tour and all other Insider Tours can be found on the Doors Open website.

More than 200 people have already registered online to volunteer, but 250 more volunteers are still needed. All volunteers will receive a Doors Open Pittsburgh t-shirt, free admission to the event with front-of-the-line privileges, and an invitation to the post-event celebration. Register to volunteer at www.doorsopenpgh.org/volunteer/.

Check out www.doorsopenpgh.org to learn more, to see the list of participating buildings, and to buy tickets for the event and/or Insider Tours. General admission for adults will be $8 for one day or $12 for both days. Admission is free for individuals under 18 or over 65 years of age. Tickets are still required, so please go online to get yours.

Insider Tours are separate from event tickets, are not included in general event admission, and need to be reserved in advance; they vary in price.

Save the dates and plan on attending Doors Open Pittsburgh, October 7 & 8, 2017!

-

Students Propose Solutions for Vacant Grant Street Lot

Westmoreland County Students Propose Solutions for Grant Street Lot that Chicago Company Hopes to Repurpose

The following story is by Ilana Kisilinsky, who is majoring in Media Studies at Yeshiva University in NYC and is spending the summer as a volunteer intern with PHLF.

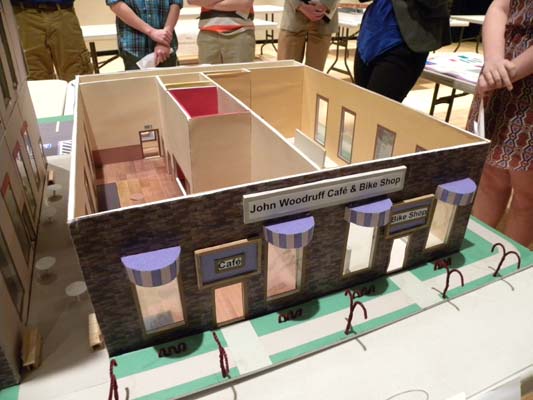

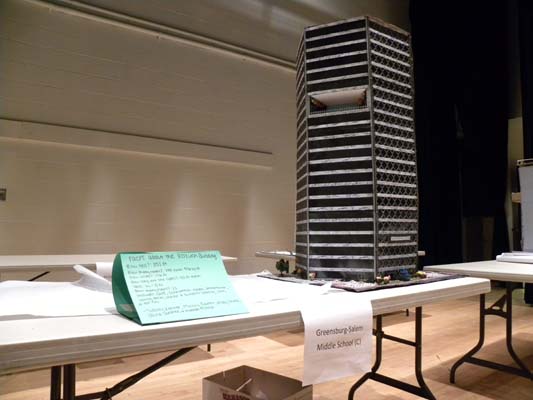

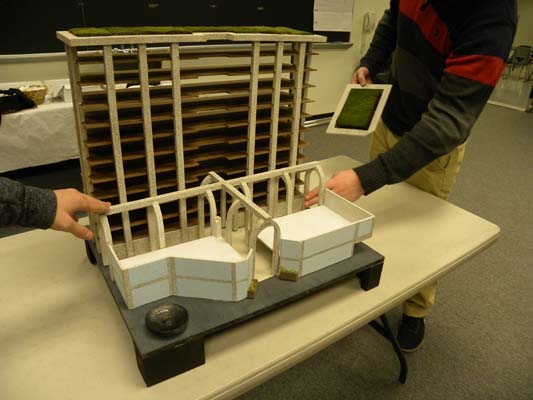

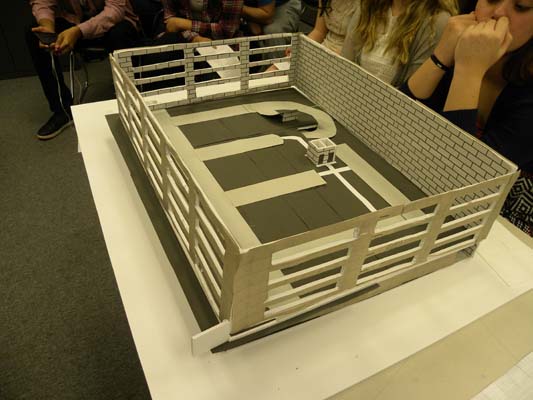

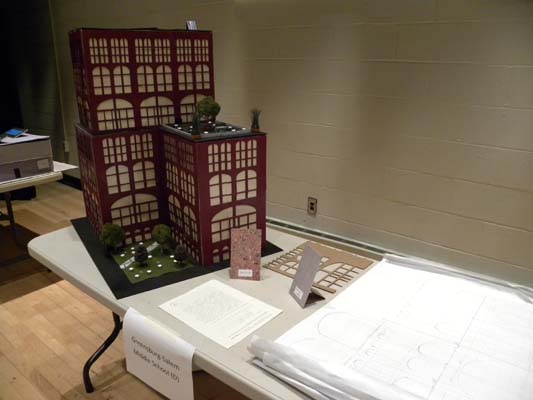

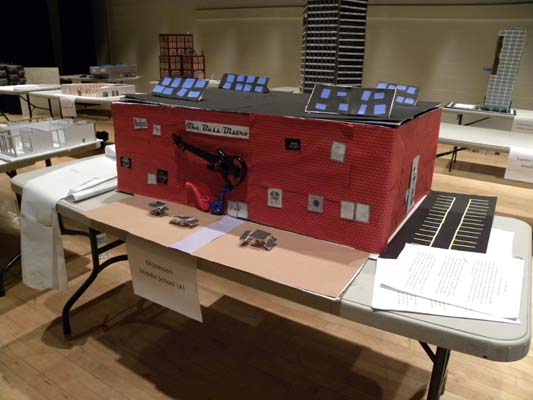

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported on June 6, 2017, that the Chicago-based company, InterPark Holdings, is looking for a developing partner to revitalize and repurpose a prime Grant Street lot that has been used for years as a surface parking lot. By coincidence, just three months before, on March 30 and 31, more than 120 students from Westmoreland County Schools had presented their ideas for that very Grant Street lot, in response to PHLF’s 21st Annual Architecture Design Challenge.

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported on June 6, 2017, that the Chicago-based company, InterPark Holdings, is looking for a developing partner to revitalize and repurpose a prime Grant Street lot that has been used for years as a surface parking lot. By coincidence, just three months before, on March 30 and 31, more than 120 students from Westmoreland County Schools had presented their ideas for that very Grant Street lot, in response to PHLF’s 21st Annual Architecture Design Challenge.The developers will be inspired to know that middle school and high school teams from Westmoreland County envisioned many innovative and creative uses for the site. “I think the most valuable thing [I learned] is how important it is to make cities cohesive,” said one of the participating high school students. InterPark Holdings is working hard to develop the site so it does become an integral part of downtown and fits within its prestigious neighborhood. “All development options will be considered for the site, including residential, office, hotel and retail,” according to the article.

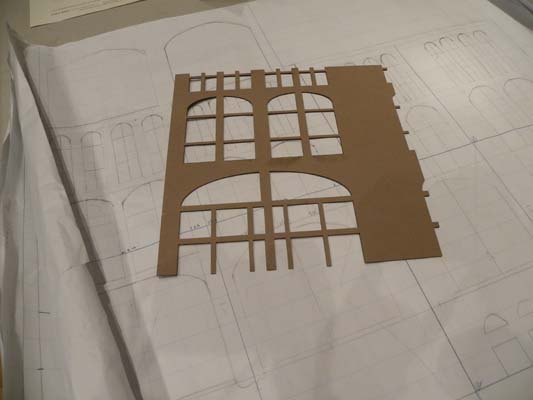

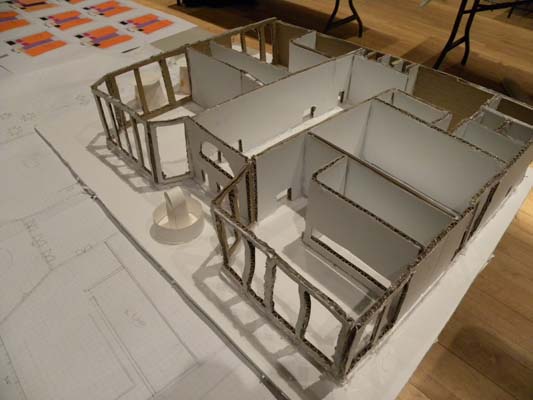

In its annual design challenges, PHLF asks middle school and high school students to think outside the box. From October 2016 through March 31, 2017, more than 120 students from nine schools in Westmoreland County were divided into 28 teams (22 middle school and 6 high school). They were tasked with creating a master plan for the Grant Street parking lot and building a model showing an architectural element that was integral to the design concept. Inspirational words from David Lewis, Pittsburgh’s distinguished urban designer, were included in the orientation packet that was given to the students when they toured the Grant Street site and area on October 14, 2016. Mr. Lewis’ words reminded the students that architects hover between the future, with the buildings they are creating, and the past, by being inspired by the great works that came before them. Buildings tell stories, not just for us, but for generations. With this in mind, Nicole Kubas of Urban Design Associates emphasized to the students that their designs must be contextual and contribute coherence and beauty to Grant Street.

The students prepared for several months, putting time and energy into designing and constructing something amazing. They met with their teams, deliberated, and worked together to create a plan that would add to the city of Pittsburgh. During final presentations at Monessen High School on March 30 and 31, the students explained their models and drawings to a jury of architects. Their written reports were bound in a booklet and are archived at PHLF.

The student projects were filled with wonderful and unique ideas including: the “Clemente Sports Bar and Grille” and “The Frick Multi-Purpose Building, to give handicapped people a living space and to supply food.” Magnet schools were also suggested, such as the “George Shiras High School for Criminal Justice and Law,” appropriately located across the street from the City-County Building and the Courthouse, as well as an art school where “kids and adults can both make great experiences in Pittsburgh. … Students who enroll, for free, can practice and/or create whatever art they major in.”

“We are always inspired by the concepts that the students propose and are amazed by their presentations and model-making abilities,” said Executive Director Louise Sturgess. “After touring the area and spending so many months working through the Design Challenge, the students become absorbed in their work and committed to their ideas. During the design-challenge process, they strengthen their skills in math, art, science, language arts, and social studies and improve teamwork and problem-solving skills.”

The student’s presentations and remarkable ideas clearly showed the effort they put into this project and the passion they felt for it. “The students loved this project,” said one of the teachers involved. “They did everything on their own, so this was a great learning experience for them. Not only did they learn how to build their projects, they learned necessary and valuable social skills as well. ‘They were so proud that they did it all on their own!’”

The students now have a better understanding of the work that InterPark Holdings has ahead of them, and wish the developers the best of luck.

-

Architecture Feature: William Halsey Wood in Pittsburgh

“Completely original and unprecedented”: William Halsey Wood in Pittsburgh and Southwestern Pennsylvania

By Albert Tannler

In 1937, Ralph Adams Cram, then this country’s leading church architect, wrote the preface to a book about a New Jersey architect who had been dead for 40 years and whom he had never met. This architect had been, Cram wrote, “a man of genius whose name, after so many years, has been forgotten by all but a few of my own generation and profession.” [1]

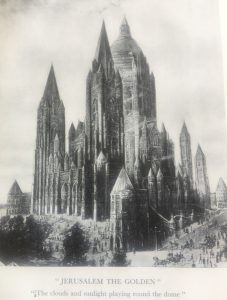

In 1937, Ralph Adams Cram, then this country’s leading church architect, wrote the preface to a book about a New Jersey architect who had been dead for 40 years and whom he had never met. This architect had been, Cram wrote, “a man of genius whose name, after so many years, has been forgotten by all but a few of my own generation and profession.” [1]The architect was William Halsey Wood (1855-1897), perhaps best known for his 1888 competition design for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City. Wood’s design, “Jerusalem the Golden,” was one of four finalists. Although the commission went to another firm, Wood’s design was displayed at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893 and won a gold medal.

“Halsey Wood’s design,” Cram wrote, “was neither Richardsonian nor Victorian Gothic, nor indeed quite like anything else ever recorded in history; it was an artistic tour de force, completely original and unprecedented.”[2] Had Wood’s design been chosen:

it might very possibly have considerably modified the course of development in American architecture. In a sense he anticipated [Louis] Sullivan, [Frank Lloyd] Wright, [Bertram] Goodhue and the other path-breakers towards modernism …. Halsey Wood indicated the possibility of a rather convincing amalgamation of historic tradition and a revivifying modernism, and he very well might have become the leader of a new school of design.[3]

Wood was, Cram concludes, “a great and creative artist, measurably in accomplishment, but greater still in potentiality.”[4]

Wood’s designs for Southwestern Pennsylvania included:

- the Carnegie Library of Braddock (1888-89), which was the first library building in the United States to be funded by Andrew Carnegie;

- a design for the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh,

illustrated in the American Architect & Building News, May 21, 1892, but not realized;

illustrated in the American Architect & Building News, May 21, 1892, but not realized; - the Church of the Good Shepherd in Hazelwood (1891-92), characterized as “rather fantastic”[5] by the region’s leading architectural historian, James D. Van Trump;

- St. Peter’s Episcopal Church, Butler, Pa. 1895-96)[6]; and

- the Church of the Ascension (1896-98) in Pittsburgh. [7] Wood was given the commission and completed the design, but he died of tuberculosis on March 13, 1897 at the age of 41. The architectural drawings were received from his estate and the building was erected by Alden & Harlow, whose predecessor firm, Longfellow, Alden & Harlow, had added the music hall to Wood’s Braddock Library in 1893. Wood’s design draws upon Late English Gothic forms. The interior is yellow Kittanning brick (now painted) with a great wooden ceiling and arresting saw-tooth chancel arch; the rough stone exterior is dominated by a Tudor tower modeled after one of 1506 in Wrexham, Wales. Van Trump, in his 75th Anniversary article on Ascension, states:

It is the rugged, masculine mass of the building, the rock-like texture of its walls and the paucity of ornament which give an especially ‘Pittsburgh’ tone and feeling to the structure. Wood, like Richardson before him in the design of the great Allegheny County Court House and Jail, succeeded almost spectacularly in interpreting the spirit of the Steel City.[8]

The church furnishings were designed by J. & R. Lamb Studios of New York City; eighteen stained glass windows were designed and made by Healy & Millet of Chicago

––George Healy and Louis Millet had attended the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris with Louis Sullivan and these artists frequently worked together; and in 1918-19, redecoration of the small chapel on the south side of the chancel began, supported by the Gordon family. Ralph Adams Cram designed the Chapel and the six small antique glass windows are the work of Charles J. Connick of Boston, Cram’s preferred glazer (who grew up in Pittsburgh and apprenticed in glass studios here).

Although Connick’s glass in the Gordon Chapel consists of simple gray and blue “grisaille” panels, colorful saints eventually filled the clerestory windows that Healy & Millet left empty. The antique glass windows were designed and made by Howard Wilbert of Pittsburgh Stained Glass Studios (1918) and George Hunt of Hunt Studios (1962-64) and are ambitious local examples of Modern Gothic glassmaking. The installation of the last of these windows in 1964 concluded the dialogue between architects, designers, and craftsmen begun in 1896.

One of the most interesting and satisfactory ecclesiastical buildings that Wood designed and completed during his lifetime is the Church of the Good Shepherd (1891-92) in Hazelwood. Van Trump observed in 1967:

This asymmetrical and rather fantastic structure with its frilled shingle tower recalls very pleasantly the rugged, stylish “natural” contours of those late nineteenth century suburban churches boldly designed by a small number of “original” architects, a group that might be described as the “boulder and shingle” school. . . . The church should be preserved as a unique local representative of its type.[9]

In 1997 Walter Kidney wrote:

Good Shepherd has an artfully rustic expression. An industrial town has grown around it, yet with its low walls of rubble and dark-red brick, its prominent roof, its much louvered, shingled little tower it announces itself as a simple country church. Such a quality of sophisticated humility, a practice of rejecting pompous gestures and ornamental displays in favor of plain materials and vernacular forms––yet composing these with a very knowing eye––had begun early in the Romantic period and would persist far into the twentieth century.[10]

The stained glass windows were designed and made by Ludwig Grosse (1862-1917), born and educated in Munich, Germany. Grosse arrived in Pittsburgh in 1888. In 1889 he began to work in stained glass; in 1890 he was working for the Pittsburgh glass firm of S.. S. Marshall & Brothers, purchased their downtown studio and opened the L. Grosse Art Glass Company, which continued under his name through 1898. In 1899 and 1900 he is listed as a dealer in “art works.” Grosse appears to have left Pittsburgh thereafter.

In 1897, Gross hired William Willet of Philadelphia, who moved to Pittsburgh and became art director of the L. Grosse Art Glass Company; in 1899 Willet established his own firm, Willet Stained Glass & Decorating Company, in Pittsburgh.[11]

In 1897, Gross hired William Willet of Philadelphia, who moved to Pittsburgh and became art director of the L. Grosse Art Glass Company; in 1899 Willet established his own firm, Willet Stained Glass & Decorating Company, in Pittsburgh.[11]Gross’s work at The Church of the Good Shepherd was described in The Bulletin (October 29, 1892):

The dedicatory services of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd, Hazelwood . . . will take place tomorrow morning . . . . The inside is beautifully frescoed and the windows, made from designs by Mr. Ludwig Grosse, of this city, are both handsome and artistic.[12]

Illustrations:

- “Jerusalem the Golden”

- Church of the Good Shepherd – exterior

- Church of the Good Shepherd – interior

- Robert S. Johnston Memorial window, designed by Ludwig Grosse.

[1] Ralph Adams Cram, “Preface.” Memories of William Halsey Wood By His Wife (Privately printed 1937), 9.

[2] Ibid., 10.

[3] Ibid., 11

[4] Ibid., 13.

[5] James D. Van Trump, “Church of the Good Shepherd,” Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 1967), 121.

[6] Butler is 29 miles north of Pittsburgh; the first service at this church was held January 17, 1897.

[7] The primary sources for information about the Church of the Ascension are James D. Van Trump, “Pittsburgh’s Church of the Ascension,” The Charette 36:6 (June 1956), 14-16, 29, reprinted in Life and Architecture in Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh History & Landmarks, 1983), 171-176, and Van Trump, “The Church of the Ascension, Pittsburgh: A Brief Chronicle of Its Seventy-Five Years,” Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine 48:1 (January 1965): [1-18], 15; 17. Van Trump’s research notes are preserved in the James D. Van Trump Library, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. See also Marilyn P. Whitmore, Centennial History: Church of the Ascension 1889-1989. Pittsburgh: Privately printed, 1989.

[8] Van Trump, “A Brief Chronicle,” 10.

[9] Van Trump, Landmark Architecture of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (PHLF 1967): 121.

[10] Kidney, Pittsburgh’s Landmark Architecture: The Historic Buildings of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County (PHLF 1997): 459.

[11] See Albert M. Tannler, William Willet in Pittsburgh 1897-1913: A Research Compendium (PHLF 2005).

[12] See also “Ludwig Grosse Art Glass Company,” History and Commerce of Pittsburgh and Environs: Consisting of Allegheny, McKeesport, Braddock and Homestead 1893-1894 (New York: A. F. Parsons Publishing Co., 1893): 83.