Category Archive: PHLF News

-

The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You Is Available from PHLF

As a relatively recent transplant to the City of Pittsburgh, The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You will help me understand and get in touch with the soul of my new home as I work to introduce this city to others. ––Caroline Mount, Public History Graduate Student, Duquesne University

As a tenant of a historical property, we will use these books to educate our staff to answer our guests’ questions. ––Brian George, Grand Concourse Restaurant, Station Square

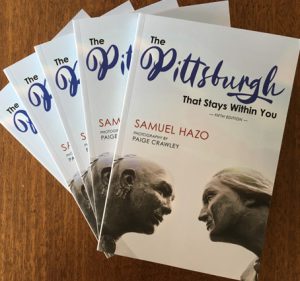

Thanks to a generous grant from The H. Glenn Sample Jr. MD Memorial Foundation, PHLF has copies of The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You, by Samuel Hazo, to distribute to schools, libraries, historical sites, and nonprofit organizations. A distinguished poet, author, and professor, Mr. Hazo was the founder and director of the International Poetry Forum in Pittsburgh from 1966 to 2009. This collector’s edition includes five essays by Samuel Hazo, written in 1986, 1992, 1998, 2003, and 2017, and photographs by 16-year-old Paige Crawley.

Thanks to a generous grant from The H. Glenn Sample Jr. MD Memorial Foundation, PHLF has copies of The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You, by Samuel Hazo, to distribute to schools, libraries, historical sites, and nonprofit organizations. A distinguished poet, author, and professor, Mr. Hazo was the founder and director of the International Poetry Forum in Pittsburgh from 1966 to 2009. This collector’s edition includes five essays by Samuel Hazo, written in 1986, 1992, 1998, 2003, and 2017, and photographs by 16-year-old Paige Crawley.Following the book’s release this fall, PHLF has distributed more than 550 books to more than 30 organizations, including the Carnegie Libraries of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County libraries, regional university libraries, public and parochial schools, community development professionals, the City of Pittsburgh, and Allegheny County Bar Association.

Please contact Louise Sturgess, PHLF’s Executive Director, with your request if you are interested in receiving books to use for educational purposes: louise@phlf.org; 412-471-5808, ext. 536. We are happy to honor requests while supplies last.

-

Envisioning New Uses for a Vacant Lot in Homestead

I learned a lot about the history of the Homestead area. It was interesting to learn to take into account the balance between contextualization and creativity when designing. The program helped me be creative and utilize space. ––High School Apprentice

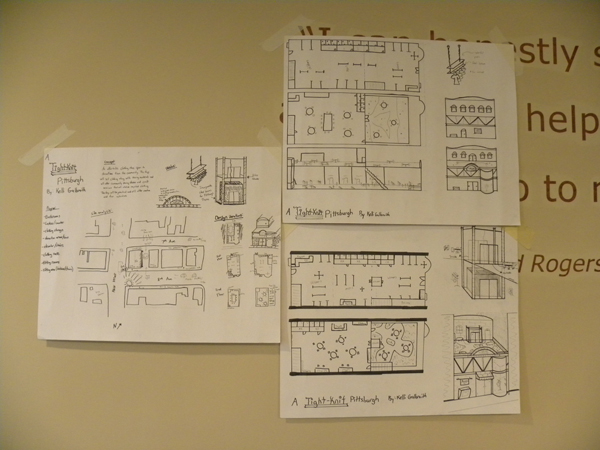

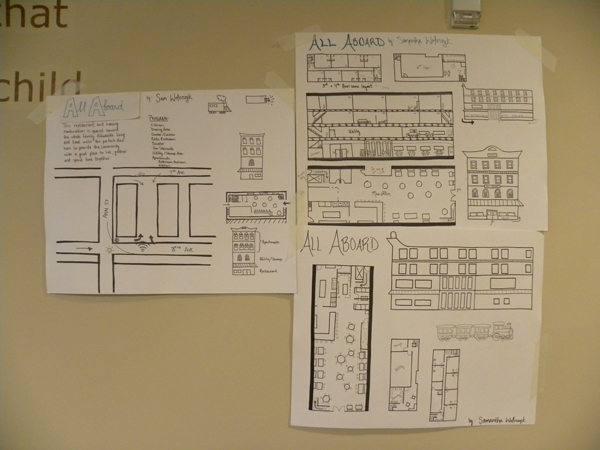

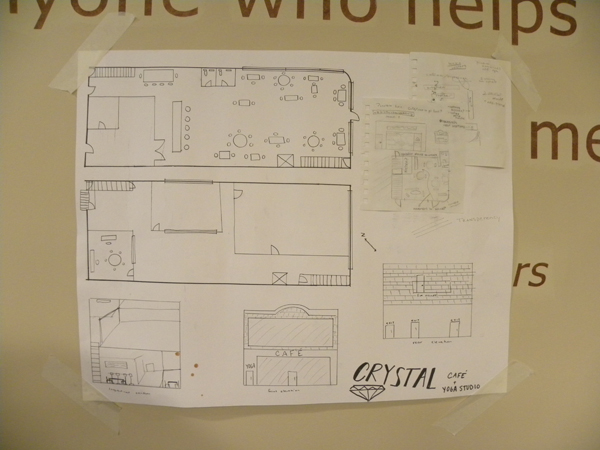

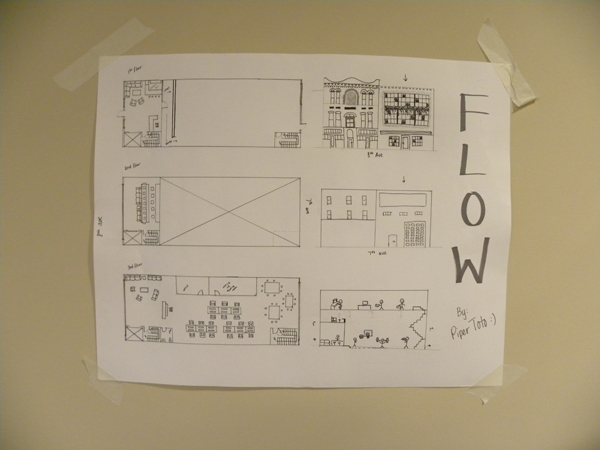

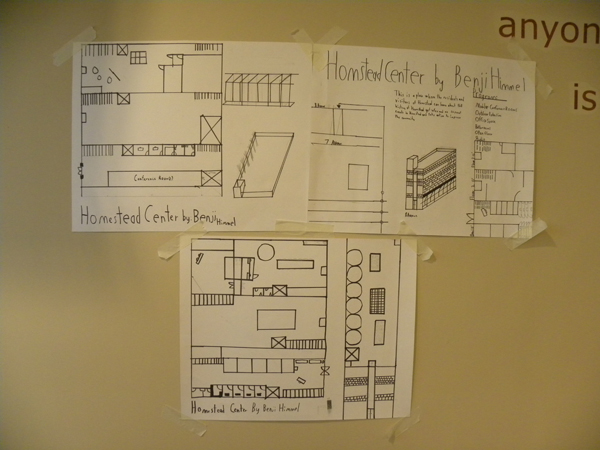

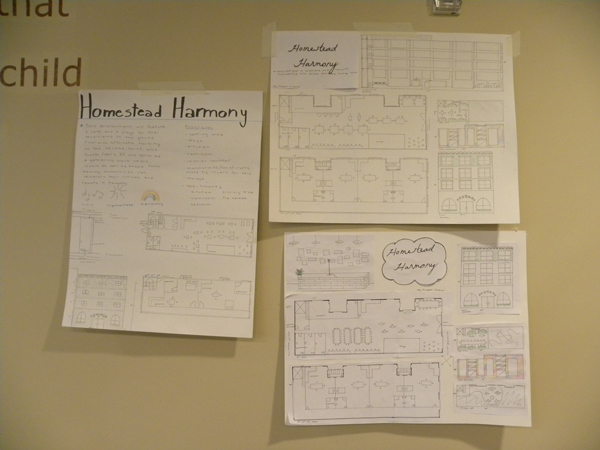

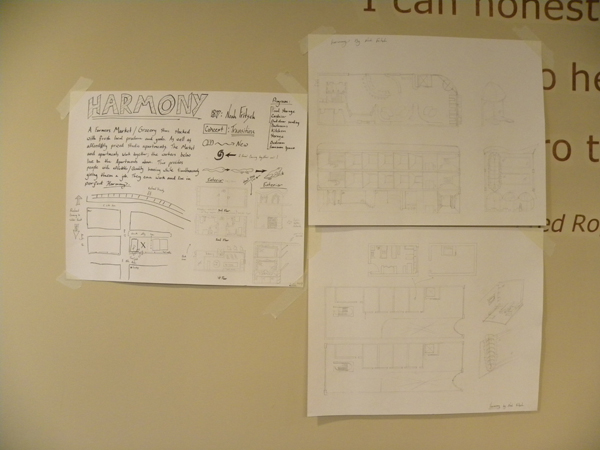

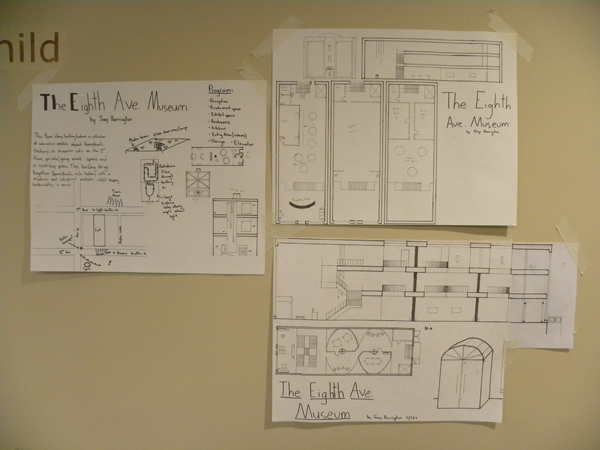

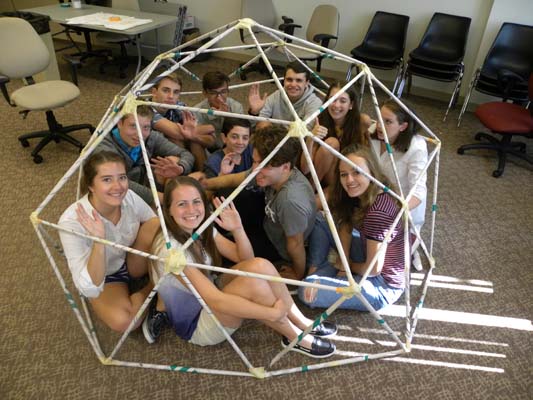

High school students from the City of Pittsburgh, Deer Lakes, Fox Chapel, Franklin Regional, Mt. Lebanon, North Allegheny, Shaler, and Upper St. Clair participated in PHLF’s Architecture Apprenticeship program, offered through the Allegheny Intermediate Unit, in the fall of 2017. After learning about the design process, visiting their design site at 307-09 East Eighth Avenue in Homestead, and touring various places for inspiration, students presented their designs to a jury of architects on December 7, 2017.

David Lewis, a founding trustee of PHLF and a distinguished urban designer, reminded the students that “the past is the living tradition that we all inherit. We take the city as we find it, in all its problems, appreciating what exists and envisioning what can be. In your project, you are re-stitching the urban fabric: you are visualizing what can be on Homestead’s historic main street.”

The photo gallery below shows the vacant lot at 307-09 East Eighth Avenue in Homestead and the design concepts presented by eight high school Apprentices on December 7, 2017. Their drawings show a:

- sewing/crafting/clothing donation center;

- train-themed restaurant;

- yoga studio and coffee shop;

- gym, smoothie bar, and office space;

- community center with exhibits, a recording studio, and rooftop garden;

- mixed-used building with a cafe, affordable housing, a stage for local talent, and a rooftop garden;

- farmer’s market, grocery store, community space, and housing;

- and museum with space for a cafe, community gatherings, and private room rentals.

The apprentices described their experiences during PHLF’s five-session crash course in architecture as: “eye-opening, inspiring, enlightening, making history modern, thought provoking, well organized, unique, exciting, helpful, educational, and fun.” Thanks to the Allegheny Intermediate Unit, PHLF has been presenting its Architecture Apprenticeship program since the early 1980s.

-

Architecture Feature: Usonian Architecture in Metropolitan Pittsburgh

The idea for the Taliesin Fellowship had come to Mr. and Mrs. Wright at the depth of the Depression in 1932 when . . . architectural commissions had dribbled to zero. If there where no buildings to build, they thought, why not build “builders of buildings”? Mr. Wright was then 65 years old, an age when most people retire. But he was as youthful and fit as a man half his age and full of creative energy.— Cornelia Brierly, Tales of Taliesin, 1999

The Taliesin Fellowship

In 1932 Wright and his third wife Oglivanna created an apprentice program for young architects and would-be architects (it was not mentioned in the first edition of An Autobiography (1932) although it figures prominently in later editions). The Wrights’ plan combined innovative educational theory, Depression-era economic reality, and elements of 19th-century architectural apprenticeship. Those who sought architectural training in the 1880s had not been obliged to attend schools of architecture (although several fine ones existed) but could choose to work as apprentices under the direction of the senior staff in the office of an established architect. Wright had done this himself, working for J. Lyman Silsbee, W. W. Clay, and Adler & Sullivan, and he had established an apprentice system in his Oak Park studio in the 1890s.

The apprenticeship program he established in 1932 was called the Taliesin Fellowship, after Wright’s Wisconsin home. Apprentices paid a fee to work on Wright designs under Wright’s direction in the nearby Hillside School building, a private educational facility Wright designed for his aunts in 1901. In addition, the apprentices maintained the Taliesin buildings, worked on the Taliesin farm, shared food preparation duties, displayed their musical and theatrical talents, and participated in a communal existence revolving around the life and work of a master architect. The Taliesin Fellowship would be an integral part of Wright’s remaining 27 years which saw the design of some of the most acclaimed buildings of his career. Since his death in 1959, the Taliesin Fellowship has been one of the principal heirs of Wright’s estate.

Wrightian Design Centered in Southwestern Pennsylvania

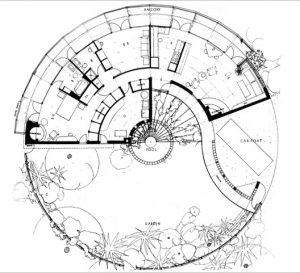

Fallingwater, Frank Lloyd Wright’s great retreat for the Kaufmann family, was designed in 1935 and completed in 1938. During the 1930s Wright also explored more modest designs for moderately-priced homes suitable for 20th-century American lifestyles—a preoccupation of his throughout his career(s). He now called such houses “Usonian” (adapted from United States of America) and the house he designed in 1937 for the Jacobs family near Madison, Wisconsin is widely considered the first. Although the appearance of Usonian houses was not uniform, each house contained standardized elements to reduce construction costs while providing the kind of domestic environment Wright considered desirable—flat roofs, a carport instead of a garage, no basement, a heating system embedded in the floors, built-in indirect lighting, built-in furniture, natural wood cladding (rather than plaster or paint). Like all Wright houses, however modest, a fireplace was essential. Brick, stone, and wood were considered desirable building materials.

Cornelia Brierly and Peter Berndtson

One reader of An Autobiography was Cornelia Brierly, a Pittsburgh-area resident and Carnegie Institute of Technology architecture student. Inspired by the book and dissatisfied with her course of study, Cornelia applied for admission to the Taliesin Fellowship; she arrived in 1934 and was there while Fallingwater and the major projects of the 1930s were designed and constructed.[1] In 1938, Peter Berndtson, a Massachusetts native who had studied architecture at M.I.T., joined the Fellowship. Peter had worked as a painter and set designer in New York City, later apprenticing with an architectural firm there. Peter and Cornelia were married in 1939.

One reader of An Autobiography was Cornelia Brierly, a Pittsburgh-area resident and Carnegie Institute of Technology architecture student. Inspired by the book and dissatisfied with her course of study, Cornelia applied for admission to the Taliesin Fellowship; she arrived in 1934 and was there while Fallingwater and the major projects of the 1930s were designed and constructed.[1] In 1938, Peter Berndtson, a Massachusetts native who had studied architecture at M.I.T., joined the Fellowship. Peter had worked as a painter and set designer in New York City, later apprenticing with an architectural firm there. Peter and Cornelia were married in 1939.In 1939 Cornelia designed Southwestern Pennsylvania’s first Usonian house for her aunts, Hulda and Louise Notz, in West Mifflin outside of Pittsburgh.[2] Soon after, the Berndtson’s moved to Spokane, Washington, returning when possible to Taliesin. In 1946, Cornelia and Peter and their two daughters moved to Laughlintown, PA, near Ligonier in Westmoreland County and established their architectural practice.

They designed buildings together for over a decade and divorced in 1957. That year. Cornelia decided to return to Taliesin as an interior designer and landscape architect with Taliesin Architects and instructor at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture.[3] Peter moved into Pittsburgh and established an office in East Liberty where he practiced until his death in 1972.[4]

The work of Cornelia Brierly (1913-2012) and Peter Berndtson (1909-1972) is not as well known as it should be. Both were trained by Frank Lloyd Wright, and together and separately they created some of the finest Wrightian residential architecture to be found anywhere.[5] Beginning with the Notz House of 1939 and taking into account their e

leven-year joint practice and Peter’s work between 1958 and 1972, almost 90 designs have been documented. Most are residential, and while buildings were erected as far East as Franconia, New Hampshire, with one outside of Harrisburg and three near State College, most of the constructed buildings are in Westmoreland and Allegheny Counties.

leven-year joint practice and Peter’s work between 1958 and 1972, almost 90 designs have been documented. Most are residential, and while buildings were erected as far East as Franconia, New Hampshire, with one outside of Harrisburg and three near State College, most of the constructed buildings are in Westmoreland and Allegheny Counties.Many of the more ambitious projects were never realized: 3 of the 8 houses planned at Meadow Circles in West Mifflin (1947-50) were erected; St. Michael’s in the Valley Episcopal Church, Rector, PA (1951), although a modification of Peter’s design for the Parish House was erected in 1970; and an apartment building, multi-unit, and single-family dwellings on a 72-acre section of Mt. Washington (1957).

Cornelia Brierly and Peter Berndtson were able to realize approximately 40 constructed buildings of extraordinary quality, inspired and nurtured by Frank Lloyd Wright; they are masterworks of the next generation, progeny of the architectural community the older and wiser Wright did not deny.

Albert M. Tannler

PHLF E-News, December 2017[1] Many of Cornelia’s writings during the 1930s are included in Randolph C. Henning, ed., At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship 1934-1937 (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1992): 58, 82, 85-87, 92, 94-95, 103, 110-12, 125-127, 129, 130, 139, 144, 151-55, 159-60, 170, 310.

[2] See Cornelia Brierly, “Notz House: A Shelter of Warmth and Rest,” Pittsburgh Tribune Review Focus 24:32 (June 13, 1999): 9.

[3] Cornelia Brierly, Tales of Taliesin: A Memoir of Fellowship (Arizona State University 1999).

[4] For Peter Berndtson’s work see Aaron Sheon. The Architecture of Peter Berndtson [An Exhibition of Contemporary Architectural Drawings, Photographs and Color Slides, The University Art Gallery, March 28th through April 18th, 1971] (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 1971) and Donald Miller and Aaron Sheon, Organic Vision: The Architecture of Peter Berndtson (Pittsburgh: The Hexagon Press, 1980).

[5] See James D. Van Trump, “Peter Berndtson, Pittsburgh Architect,” Carnegie Magazine 55:9 (November 1981, 27-29); Charles Rosenblum, “Precedent and Principle: The Pennsylvania Architecture of Peter Berndtson and Cornelia Brierly,” Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly (Spring 1999): 12-15. Two houses designed jointly and one house designed by Peter Berndtson are in Tobias S. Guggenheimer, A Taliesin Legacy: The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Apprentices (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995): 27, 30, 37, 71, 98-101.

-

“The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You” Is Available from PHLF

Our library prides itself on having a strong collection containing Pittsburgh history and Pittsburgh authors. This is an excellent addition to our collection. Thank you! ––South Park Township Library

I am going to use this book as a reflective tool in order to engage my 12th-grade students in conversation on the history and changes in Pittsburgh. ––The Neighborhood Academy

Thanks to a generous grant from The H. Glenn Sample Jr. MD Memorial Foundation, PHLF has a quantity of The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You, by Samuel Hazo, to distribute to schools, libraries, and nonprofit organizations. A distinguished poet, author, and professor, Mr. Hazo was the founder and director of the International Poetry Forum in Pittsburgh from 1966 to 2009. This collector’s edition includes five essays by Samuel Hazo, written in 1986, 1992, 1998, 2003, and 2017, and photographs by 16-year-old Paige Crawley.

Following the book’s release this fall, PHLF has distributed more than 450 books to more than 25 organizations, including the Carnegie Libraries of Pittsburgh, Allegheny County libraries, regional university libraries, public and parochial schools, community development professionals, the City of Pittsburgh, and City of Asylum.

Please contact Louise Sturgess, PHLF’s Executive Director, with your request if you are interested in receiving books to use for educational purposes: louise@phlf.org; 412-471-5808, ext. 536. We are happy to honor requests while supplies last.

PHLF has received many notes of thanks from the various organizations that have received The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You, by Samuel Hazo, including the following:

Thank you for the generous gift. People are interested in learning about their community. Everyone will learn something new from reading The Pittsburgh That Stays Within You. ––Green Tree Public Library

I will offer this book to our students to read, especially when they are studying the history of Pittsburgh. ––Urban Pathways Charter School

Great author! Has a relationship with our school. Thank you! ––Chatham University

Sam has visited our campus many times and we are always interested in his work. We also have a local history collection and a Public History class taught on campus. Thank you very much. ––Waynesburg University Library

With the college being so close to Pittsburgh, it’s nice to have books like this for our students to read. Sometimes students conducting undergraduate research like to have local history source material for their projects. The photographs are a special touch, reminding our students that creativity at any age should be encouraged and lauded. ––Westmoreland County Community College

This gift will be added to our book collection within our library to be enjoyed by our nearly 500 residents who call Asbury Heights home. ––Asbury Heights

-

Greene County Heritage Workshop

More than 40 owners and caretakers of historic buildings in Greene, Washington, and Fayette counties gathered in Waynesburg on November 4 for the first “Greene County Heritage Workshop: How to Care for Your Historic Building(s),” sponsored by PHLF and 16 local co-sponsors. A full-day’s program of preservation topics, resources, and inspiration was presented by state, regional, and local officials, along with PHLF staff and local experts.

At the end of the day, one participant wrote: “Names of sources, details and examples were excellent. I feel overwhelmed but I now have a road to follow.” Another wrote: “It was a very enlightening day.”

The program began with Bill Callahan, Western PA Community Preservation Coordinator of the State Historic Preservation Office (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission), stating that “It is an economic imperative for communities like Waynesburg to use historic preservation as a 21st-century development strategy. Heritage tourism is a major industry. By saving historic places, a community provides meaningful, authentic experiences for citizens and for visitors––and maintains a sustainable, healthy built environment. Preservation is a design ethic for creating sustainable, livable communities in the 21st century.”

Johnna Pro, Regional Director of Community Affairs for the PA Department of Community and Economic Development, explained that the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development (DCED) has matching fund programs for community revitalization. They are very competitive, but if you have a good solid project, she wants to hear about it. DCED encourages communities to find corporate sponsors to partner with them since corporations receive tax credits through the Neighborhood Partnership Program. She also recommended the community development program of the Federal Department of Agriculture.

Architectural historian Lu Donnelly shared images and information on the many architectural treasures in Greene County. She showed examples of the buildings that contribute to Greene County’s significant architectural heritage, including farms and outbuildings, covered bridges, historic religious properties, residential buildings, a rare, surviving coal patch town, main streets, civic and commercial buildings, rural churches, and academic buildings ranging from one-room school houses to universities.

Clare and Duncan Horner spoke about their c. 1880 farm of 70 acres in Greene County. Since their goal is to keep the land together and maintain the historic buildings, they donated a conservation easement to PHLF, thus protecting the farm and buildings in perpetuity. The Horners talked about the process of donating an easement and the benefits that have come from their on-going relationship with PHLF.

While enjoying a complementary box lunch, participants watched “Through the Place,” a feature-length documentary highlighting the history, achievements, and impact of PHLF since its founding in 1964. The regional preservation story was set within the context of the preservation movement nationwide and includes comments from nationally recognized architects, preservationists, authors, and historians.

Practical tips were the focus of the afternoon sessions. Architect Ken Kulak and Bryan Cumberledge, Waynesburg Borough Code Enforcement Officer, emphasized that building codes are about life-safety issues. They discussed how architects and local officials can work together with property owners from the outset of a project to effectively navigate building rehabilitation projects. Historic construction expert Fred Smith showed samples and evaluated options for the repair or replacement of historic windows and doors.

Participants agreed that the workshop format was effective and would serve as a model as PHLF develops additional workshops in 2018. PHLF funded the workshop thanks to donations to its 50th Anniversary Fund. More than 65 members and foundations contributed to PHLF’s 50th Anniversary Fund between 2014 and 2017. One of the goals of that fundraising effort was to help PHLF provide technical assistance to main streets and historic neighborhoods throughout the Pittsburgh region, with a particular emphasis on outlying counties where no local preservation organizations exist to assist concerned citizens.

-

Architecture Feature: Louis Arnett Stuart Bellinger (1891-1946)

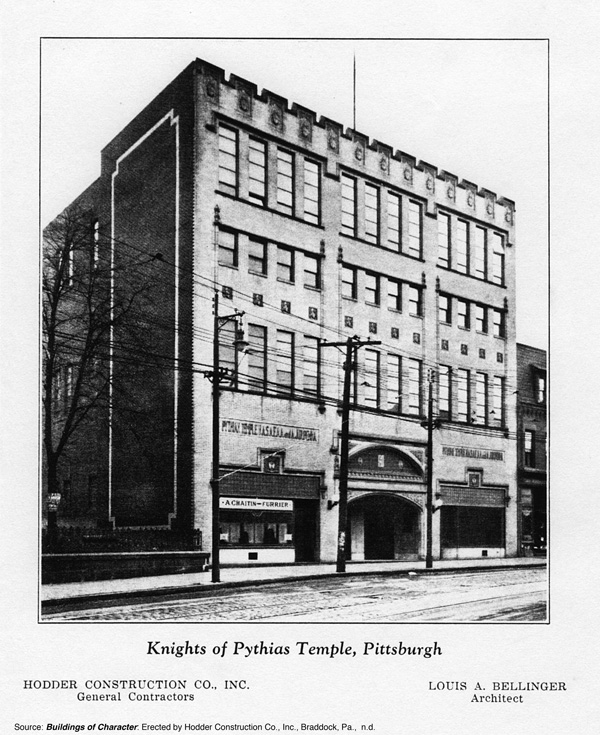

Louis A. S. Bellinger was born in Sumter, South Carolina, on September 29, 1891. He was educated in mathematics and engineering at Howard University (B.S. in Architecture, 1914), then taught mathematics at Fessenden Academy, Ocala, Florida (1914-15), and at Allen University in Columbia, South Carolina (1916-18); he took a leave-of-absence to serve in World War I in 1917. In 1919 he and his wife Ethel Connel Bellinger arrived in Pittsburgh, where he is listed as an architect in the city directory. His first major commission was designing Central Park, home field of the African-American Pittsburgh Keystones baseball team in 1920, at the request of team owner, Alexander M. Williams. In 1922 he opened an office at 525 Fifth Avenue and advertised in the Classified Business Directory. Some Bellinger commissions were listed in the Western Pennsylvania construction magazine, The Builders’ Bulletin, beginning in 1922. He joined the office of the City Architect in 1923—the first African American to be hired—and as an assistant architect he designed a police station and remodeled service buildings in the city parks. In 1926 he received a major commission for the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Book Concern in Philadelphia. A year later he won the commission to design the Pythian Temple in Pittsburgh for the African American Grand Lodge of the Knights of Pythias of North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia, Jurisdiction of Pennsylvania. The lodge/commercial building at 2007-2013 Centre Avenue was completed in 1928 and was one of the largest and most prominent secular buildings in the predominately African American Hill District, known as Pittsburgh’s Harlem.[1]

Louis A. S. Bellinger was born in Sumter, South Carolina, on September 29, 1891. He was educated in mathematics and engineering at Howard University (B.S. in Architecture, 1914), then taught mathematics at Fessenden Academy, Ocala, Florida (1914-15), and at Allen University in Columbia, South Carolina (1916-18); he took a leave-of-absence to serve in World War I in 1917. In 1919 he and his wife Ethel Connel Bellinger arrived in Pittsburgh, where he is listed as an architect in the city directory. His first major commission was designing Central Park, home field of the African-American Pittsburgh Keystones baseball team in 1920, at the request of team owner, Alexander M. Williams. In 1922 he opened an office at 525 Fifth Avenue and advertised in the Classified Business Directory. Some Bellinger commissions were listed in the Western Pennsylvania construction magazine, The Builders’ Bulletin, beginning in 1922. He joined the office of the City Architect in 1923—the first African American to be hired—and as an assistant architect he designed a police station and remodeled service buildings in the city parks. In 1926 he received a major commission for the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Book Concern in Philadelphia. A year later he won the commission to design the Pythian Temple in Pittsburgh for the African American Grand Lodge of the Knights of Pythias of North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia, Jurisdiction of Pennsylvania. The lodge/commercial building at 2007-2013 Centre Avenue was completed in 1928 and was one of the largest and most prominent secular buildings in the predominately African American Hill District, known as Pittsburgh’s Harlem.[1]Between 1927 and 1929 Bellinger posted current projects in the Pittsburgh Architectural Club/Pittsburgh Chapter A.I.A. journal, The Charette. (Unlike his white colleagues, however, his contributions were not acknowledged by the editor.) While the Pythian Temple was under construction, Bellinger was one of three black architects invited to participate in the first major exhibition of the work of African American artists in the United States, sponsored by the Harmon Foundation and held in New York City, January 5-15, 1928. In 1932 Bellinger designed Greenlee Field on Bedford Avenue in the Hill District for the Pittsburgh Crawfords baseball team. Greenlee Field, called the “finest independent ball park in the country, and one of the few black-controlled ones,” [2] opened on April 29, 1932. Later that year Bellinger became the first black candidate for Congress from the 32nd Congressional district; he lost the election. (An African American did not win a Congressional seat from Pennsylvania until 1958). In 1933 Bellinger was invited to contribute to the Harmon Foundation’s second African American art exhibition. Bellinger became the first African American hired as a City of Pittsburgh Building Inspector; he held this position from 1937-1939 and from 1941-1942. He practiced architecture briefly in 1940 and resumed his architectural career in 1943.

On February 3, 1946, Louis Bellinger died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was 54 years old. He is buried in Allegheny Cemetery in Pittsburgh. The New Granada Theater, formerly the Pythian Temple, was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 27, 2010.

[1] In 1935 the Pythians defaulted on their mortgage payments, and although ownership of the Pythian Temple would not be resolved until 1948, the lodge lost control of the building in 1936. It was remodeled by Pittsburgh architect Alfred Marks as the New Granada Theater and opened May 20, 1937.

[2] Rob Ruck, Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 156.

-

Architecture Feature: Edward Trumbull in Pittsburgh

By Albert M. Tannler

Edward Trumbull (1884-1968) was born in Michigan. He studied painting at the Art Students’ League of New York. He subsequently worked in London circa 1911 as an assistant to Frank Brangwyn.[1] According to an interview in the Pittsburgh Index in 1917, Trumbull was recommended to Henry J. Heinz by British painter Sir Alfred East (1849-1913) and received the commission to paint murals for the Heinz administration building in Pittsburgh.[2] He returned to the USA in 1911; he lived and worked in Pittsburgh between 1912 and 1920.

Trumbull exhibited sketches for “Decoration in the New Administration Building of the H. J. Heinz Company” at the 1912 Pittsburgh Architectural Club exhibition.[3] He participated at the 1912 and 1915 exhibitions of the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh (founded in 1910 and still active). In 1915 he painted two murals—“William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians” and “The Steel Industries of Pittsburgh”—for the Pennsylvania Building at the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco designed by architect Henry Hornbostel (1867-1961), who practiced in both New York and Pittsburgh. Three artworks—“Chinese Flamingo,” “Royal Dodo Bird,” and “Midsummer”—were displayed at the Pittsburgh Architectural Club exhibition of 1916-17.

Trumbull moved to New York City but continued to collaborate with Hornbostel on Pittsburgh projects, painting murals for the Supreme Court Room in the City-County Building (1923), the Eugene Strassburger residence in Squirrel Hill (1928-30), and the Grant Building lobby (1931). Trumbull’s acclaimed Grant Building mural, “The Three Rivers,” is believed to be entombed above a dropped ceiling, but his Supreme Court Room murals and ceiling paintings are breathtaking: neither as impressionistic nor as boldly colored as Frank Brangwyn’s murals, they are prodigy worthy of a master muralist.[4]

In New York City Trumbull executed the façade terra cotta bas relief on the Chanin Building, the ceiling fresco “Transport and Human Endeavor” in the Chrysler Building lobby, and murals in the Oyster Bar and Restaurant in Grand Central Terminal (1912; Guastavino tile vaulting[5]). He painted murals in the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

Select Chronological Bibliography

Associated Artists of Pittsburgh Annual Catalogues 1912, 1915.

Pittsburgh Architectural Club Exhibition catalogs 1912, 1916-17

McCord, Myra Webb. “An Atelier That is Different: Edward Trumbull’s Unusual Workshop at His East End Home—Murals Are Done In An Atmosphere Remote From Pittsburgh’s Humdrum Life—Mills Offer Great Inspiration.” The Index 36:1 (January 6, 1917), 5, 15.

Kidney, Walter C. Henry Hornbostel: An Architect’s Master Touch. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 2002, 46, 145,168, 169, 173, 230.

Horner, Libby. Frank Brangwyn: A Mission to Decorate Life. London: Fine Arts Society/Liss Fine Art, 2006.

[1] Horner 2006 shows a photograph of Brangwyn and Trumbull in the studio [116]. She notes: “Whatever qualities Trumbull may have had as an artist were forgotten when Brangwyn discovered Trumbull was a bigamist.” [242]. See “Miss Dreier Finds She is Not a Wife: Edward Trumbull, Artist, Not Legally Free When He Married Brooklyn Society Girl,” New York Times, 22 August 1911.

[2] Myra Webb McCord, “An Atelier That is Different: Edward Trumbull’s Unusual Workshop at His East End Home—Murals Are Done In An Atmosphere Remote From Pittsburgh’s Humdrum Life—Mills Offer Great Inspiration,” The Index 36:1 (January 6, 1917), 5, 15.

[3] Edward Trumbull’s Heinz Plant murals have been preserved at the Heinz History Center, the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, but are not on display. I am grateful to Kathleen Wendell for this information.

[4] Trumbull murals in Hornbostel buildings are illustrated in Walter C. Kidney, Henry Hornbostel: An Architect’s Master Touch (Pittsburgh, 2002), 46, 145, 169, 173.

[5] See John Ochsendorf, Guastavino Vaulting, 140-141.

-

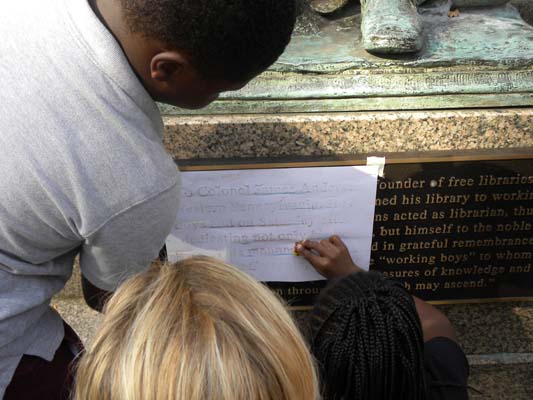

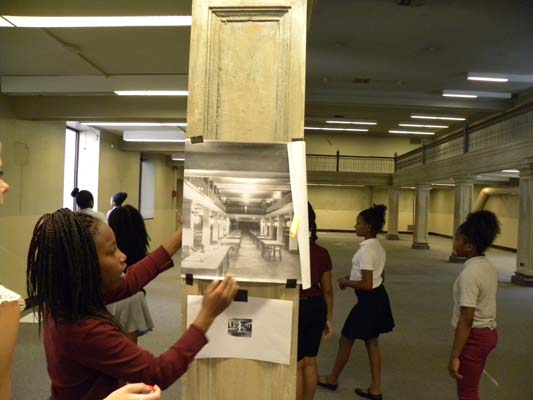

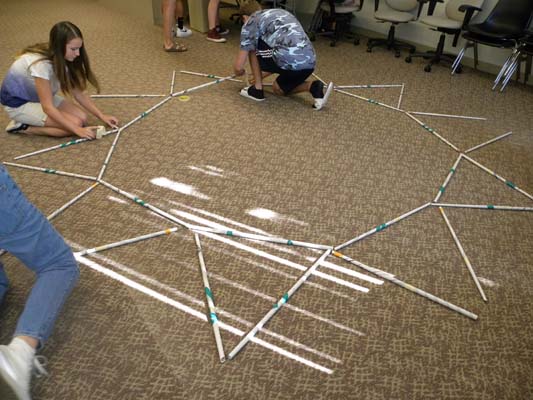

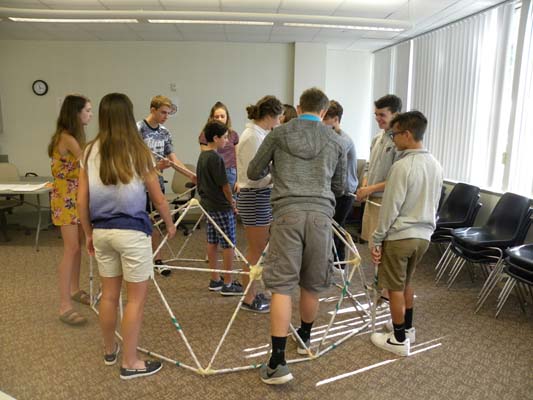

Exploring Architecture and Local Communities

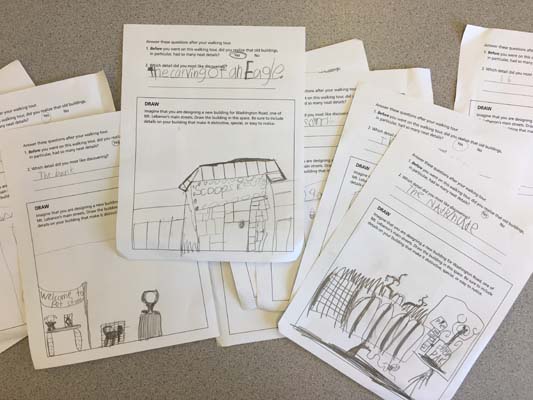

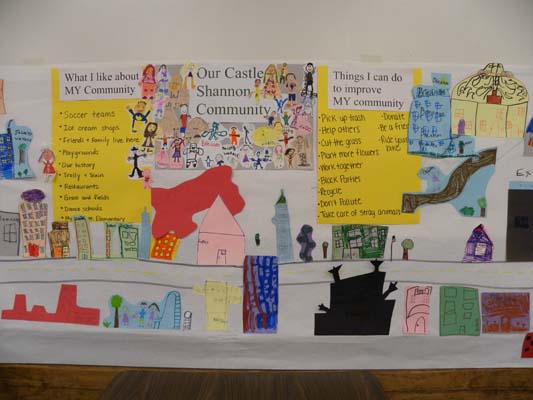

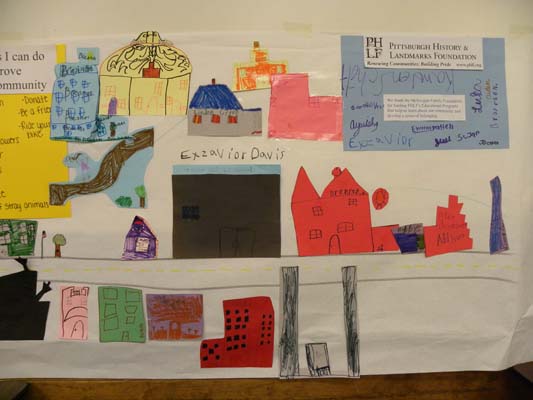

The photos below document a few of the many educational programs that PHLF hosted in September. They include architectural design challenges in Pine-Richland, Homestead, and West Newton (Westmoreland County); community explorations in Mt. Lebanon and Castle Shannon; and a chance to experience the former Carnegie Library on Pittsburgh’s North Side and talk with Tony Pitassi of Perfido Weiskopf Wagstaff + Goettel Architects before the historic building is renovated to include MACS’ new middle school.

“In all that we do, we are encouraging students to become active citizens who appreciate the importance of saving and reusing historic buildings and are capable of proposing new uses for vacant lots, based on the needs of the community,” said Louise Sturgess, executive director of PHLF. “We thank the many foundations and individuals who donate to our educational programs that serve more than 5,000 students each year. Our programs are affordable, meaningful, and lots of fun.”