Category Archive: National Historic Landmarks

-

Hotel Saxonburg Chef Returns to Recently Renovated Landmark

By Pam Starr, FOR THE PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Hotel Saxonburg's executive chef, Alan Green, and owner, Judy Ferree, with Penne Carbonara Erica Hilliard | Valley News Dispatch

Judy Ferree loved Hotel Saxonburg so much as a customer that she decided to buy the Butler County landmark in July.

The former owner, Domenic Gentile, had died a few years ago, and his wife realized she couldn’t keep the restaurant going, says Ferree, a resident of Middlesex.

“I thought this would be a good project,” says Ferree, 50, who used to own Lakevue Athletic Club with her husband, Bob, and managed Butler Country Club for a number of years. “I had watched it slide, partly due to the economy, but I wanted to get Hotel Saxonburg back to where it was.”

Ferree closed the place for five weeks for needed renovation. All of the kitchen equipment was replaced, including the refrigeration units and ventilation system, and the entire interior was painted. The original tin ceiling in the dining room was repaired and painted.

But Ferree was careful to keep the old-fashioned charm and elegance that Hotel Saxonburg is known for. Hotel Saxonburg was built in 1832 and is listed in the National Registry of Historic Places. The black-and-white checkered floor tile is still intact, and the copper-topped bar dates to the 19th century. Five upstairs sleeping rooms have been meticulously refurbished to reflect the 1800s. Ferree points out that Woodrow Wilson once stayed there.

The 138-seat Hotel Saxonburg is the oldest continually operating restaurant and bar in Butler County, she says.

“We reopened on Aug. 12, and it’s been exciting,” she says. “It’s livened up the whole community. I brought back the chef, Alan Green, who was here for 18 years and left to work at the Springfield Grill for four years. He’s the heart of the place and is so approachable and humble. He’ll be the first one to jump in and help the dishwasher.”

Green, 55, has been cooking professionally for 35 years and hand-picked the culinary team when he returned. The Aliquippa native began his career while a student at Penn State, where he graduated with a Spanish degree.

“I cooked my way through school, and my knowledge of Spanish was invaluable while working as a chef in Washington, D.C.,” he says. “When I hire someone, the first thing I look for is enthusiasm, and the ability to look me in the eye. They also need to be able to take criticism.”

Green is very pleased with the chefs and cooks who work with him at Hotel Saxonburg.

“I have some young guns here that are terrifically talented but need steady guidance,” says Green, who is married and lives in Butler. “I can’t marathon anymore at my age, so I teach. I also try to learn something every day.”

The American menu is Green’s creation. He wanted to return to the classics, he says, as well as keep up with trends. His appetizers include staples such as crab cakes, fried asparagus and shrimp cocktail. But one will also find zucchini cakes with roasted red pepper sauce; ground beef sliders; Crimini mushrooms filled with clam stuffing and topped with bacon; and grilled New Zealand lamb chops.

Hotel Saxonburg is famous for its lobster bisque, and Green wouldn’t dream of taking that off the menu. Entrees feature classics such as filet mignon, baby back ribs, chicken gorgonzola and seafood pasta. Green includes other items like sauteed black sea bass filets; satay fire-grilled chicken skewers with wild mushrooms and marinara sauce; shrimp tempura with sweet Thai chile sauce; and cucumber-crusted salmon filet with a cucumber-wasabi puree.

Everything on the menu is made from scratch, he says.

“We get our seafood from Curtze Foods in Erie, and some from Pittsburgh Seafood,” Green says. “Our chicken, lamb and beef comes from Curtze, and US Foods. Our specialty products are from Thoma’s, right down the road, and their pork is superior. Perriello Produce in Natrona Heights handles our produce. They’re all good guys.”

The hours are the hardest part of being a chef, he says, but the “happy stuff far outweighs the dark stuff.” Writing cookbooks is on Green’s bucket list, and the first one will be about soups.

“All I do is think about food,” he says with a laugh. “I read food, I study food, I watch food. Cooking is very rewarding. When you get one customer who tells you how nice their dinner was, it makes your month.”

Penne Carbonara

Chef Alan Green is sharing is popular Penne Carbonara recipe. He uses local bacon from Thoma's to give the dish more oomph, and uses an egg in the final phase to thicken the dish. Erica Hilliard | Valley News Dispatch

Chef Alan Green is sharing is popular penne carbonara recipe. He uses local bacon from Thoma’s to give the dish more oomph, and uses an egg in the final phase to thicken the dish.

“The egg is a delicious way to enhance and enrich the flavor,” says Green. “The sauce should be just thick enough to coat the noodles. This is a good, wintery pasta dish that fills you up.”

He suggests serving this hearty meal with whatever wine you enjoy.

- 3 tablespoons clarified butter

- 2 tablespoons red onion, julienned

- 1 teaspoon minced garlic

- 1/4 cup thick-sliced bacon, diced

- Salt and freshly ground black pepper, to taste

- 1/2 cup heavy cream

- 12 ounces cooked penne pasta

- 1/4 cup grated Romano cheese

- 1 large egg

- 2 tablespoons chopped parsley

Put the butter, red onion, garlic and bacon in a saute pan over medium-high heat. Sweat the onion and garlic for about 2 minutes, and season with salt and pepper.

Add the heavy cream and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat and simmer until reduced by half.

Cook the pasta according to package directions, and drain well. Add the cooked pasta to the cream mixture and season again with salt and pepper. Add the Romano cheese, and then remove from the heat. Stir in the egg and mix well.

Place the pasta in a serving bowl, sprinkle with chopped parsley, and serve immediately.

Makes 2 servings.

Hotel Saxonburg:Cuisine: American

Hours: 11 a.m.-10 p.m. Tuesdays-Thursdays, 11 a.m.-11 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays, 11 a.m.-9 p.m. Sundays

Entree price range: $10-$23

Notes: Major credit cards accepted. Handicapped accessible. Reservations recommended for weekends. Bottles of wine for $15 featured on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Sunday brunch. Five hotel rooms upstairs.

Address: 220 Main St., Saxonburg, Butler County

Details: 724-352-4200 or website

-

Allegheny West’s Annual Holiday House Tour Shows Off Style, Taste and City History

Saturday, December 04, 2010By Patricia Lowry, Pittsburgh Post-GazetteOn Thanksgiving eve, when I called Alex Watson about previewing his house for next weekend’s Allegheny West Victorian Christmas House Tour, I assumed it would be too early to see it in holiday garb.

“Oh, that won’t be a problem,” he said. “My Christmas tree has been up for three years.”

When your house has been on the tour for 28 of the event’s 29 years, leaving the artificial tree up and decorated in a corner of the library seems the expedient thing to do.

Next to it, on the mantel, stands the illuminated Dickens Christmas village Mr. Watson made decades ago of fiberboard, crowned by London’s St. Paul Cathedral and complete with Scrooge & Marley’s counting house. It’s now a year-round feature, too.

And next to that, on the wainscot ledge, stand a dozen smaller buildings closer to home, representing Allegheny West houses that have appeared on neighborhood tours. He and his neighbors made those, too, for sale to tour-goers in years past.

Anything to support his beloved Allegheny West, the North Side neighborhood in which he and his late partner, Merle Dickinson, settled in 1960, when they purchased the North Lincoln Avenue home. Then broken into 17 (now 10) apartments, it was far from the showplace it is today.

The red brick house, originally a two-story built between 1864 and 1865, was enlarged to its present three-story size and Romanesque Revival appearance in the early 1890s, when a library also was added to the front of the house.

Grain merchant John W. Simpson was the original owner; Joseph Walton bought it in 1888 for daughter Ida Walton Scully and her husband, glass manufacturer James Scully. In 1917 the house was sold to James S. Childs, a shoe, rubber and leather wholesaler whose wife Alice was Ida Scully’s sister.

In 1923 the house changed hands again; the new owners were Samuel and Margaret Crow, who lived there and rented rooms to boarders. The house stayed in the Crow family until 1960.

The library in Alex Watson's North Lincoln St. home is decorated for the holidays. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

The house’s architect is unknown; none surfaced during architectural historian Carol Peterson’s extensive house history research. Mr. Watson thinks it may have been Longfellow, Alden and Harlow, who in 1889 completed a house across the street commissioned by B. F. Jones for his daughter Elizabeth and her husband, Joseph O. Horne, son of the department store founder. It’s a good bet, considering the richly carved and paneled oak interior finishes, the melding of medieval and classical influences and a first-floor layout similar to the Horne house. The firm designed 13 buildings within a radius of several blocks and Frank Alden had lived just around the corner.

Restoring the home’s original features became a decades-long passion for Mr. Watson and Mr. Dickinson, who did much of the work themselves. And there was much work to do. While most of the interior woodwork remained, the first floor’s front parlor, library and dining room had been its own apartment with kitchen and bath.

One bathroom occupied a corner of the entrance hall; during its removal, the owners discovered a long-lost corner of the hall’s original mantel. From that remnant, they re-created the mantel and over-mantel and warmed up the room with a gas fireplace.

The hallway in Alex Watson's North Lincoln St. home is decorated for the holidays. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

Mr. Watson has his regrets, including removal of a mantel and overmantel in the front parlor to gain wall space. They recycled it as a bar and back bar in the former kitchen, now a game room outfitted as a bordello dedicated to 1920s neighborhood madam Nettie Gordon. Eventually, in atonement, they purchased a white marble Italianate mantel from a Sewickley house sale for the front parlor.

The music room in Alex Watson's North Lincoln St. home. Originally the home's dining room, the breakfront still dominates the room. The home will be on the Allegheny West Christmas House Tour. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

In the former dining room, now the music room, Mr. Watson (on the piano) and friend Mark Schumacher (on the organ) plan to greet tour-goers, as they have in years past, with songs of the season. Seeing the faces of visitors as they enter the room, Mr. Watson said, “makes the whole thing worthwhile.”

The hallway in Alex Watson's North Lincoln St. home is decorated for the holidays. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

Trained in nursery and landscape management at Michigan State, Mr. Watson managed the garden shop at Sears for 27 years before it became part of Allegheny Center. His courtyard garden, glimpsed through the oak-paneled music room windows, has been featured on neighborhood garden tours; this time tour-goers will pass through it as they leave.

The six houses on the tour, spread over three blocks, include Gretchen Duthoy’s red brick, Second Empire-style Beech Avenue home, a newbie to the event.

This home at 849 Beech Ave. will be on the Allegheny West Christmas House Tour. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

“My house was turning 150 this year,” said Ms. Duthoy, who wanted to do something to mark the occasion. She commissioned a house history from Ms. Peterson, who discovered the house in fact was 140 years old, having been built in 1870 for railroad conductor Theodore Gray and his wife Annie. The longest ownership — 1887 to 1922 — came with four generations of the family of Christian Stoner, partner in a Strip District lumber mill.

When Ms. Duthoy, an Alcoa employee who grew up in suburban Maryland, bought the house in 2003, it had been restored by its previous owners, for whom she’d worked as a baby sitter in college.

“That’s how I came to know the house and the neighborhood and that’s how I came to live there” a few years later when they had outgrown it, she said.

Her work on the house has been cosmetic, including a kitchen update. For the tour she’ll hang family ornaments on her live tree and decorate extensively with fresh greens.

The tour, she said, is “a great showcase for the neighborhood, and I’d like to do my part.”

Allegheny West Victorian Christmas House TourInformation: Guided walking tours cost $25 per person and leave from Calvary United Methodist Church, Allegheny and Beech avenues, at 12-minute intervals from 5 to 8 p.m. Friday, and 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. next Saturday, with a maximum of 25 guests per tour. Tour guides will talk about 19th-century holiday traditions and the history of the neighborhood and the homes on the tour.

At the end of the event, which lasts about three hours, tour-goers can visit John DeSantis’ miniature railroad village and toy train collection at Holmes Hall, 719 Brighton Road, for an additional $10, as well as the Holiday Shoppe at Jones Hall, with antiques, gifts and handcrafted items. Mr. DeSantis’ train collection, open to the public only during the Christmas tour, also can be visited separately; hours are 7:30 to 10 p.m. Friday and 12:30 to 10 p.m. Saturday.

Special tours include a wine tour at 6 p.m. Friday, with wine tasting and hors d’oeuvres at a private residence, followed by the house tour ($75 per person). On Saturday, brunch tours will be offered at 10 and 10:30 a.m. and high-tea tours at 3 and 3:30 p.m. ($50 per person), followed by the house tour. With help from The Center for Hearing and Deaf Services, a signed tour will be offered at 3:36 p.m. Saturday ($25 per person).

Tours are rain or shine, snow, sleet or hail. As the Allegheny West Civic Council’s website puts it, “This is Pittsburgh and bad weather is part of the charm.” Reservations are required for all tours and tickets are nonrefundable. Visit the website (alleghenywest.org) or call 412-323-8884.

-

Welcoming Vandergrift has Plenty of Special Features

By Bob Karlovits, PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Monday, November 22, 2010Many small towns have rich stories, but few tell them as well as Vandergrift.

Part of that tale is in the layout of the historic area of the 115-year-old town. Designed by the firm of Frederick Law Olmsted, the creator of New York City’s Central Park and many academic campuses, the streets arch over and around the hillside on which the town is built.

A grand theater, the Casino, sits facing a mall leading down to a train station. It was given that spot intentionally to offer a welcome to anyone arriving in the Westmoreland County town.

The town was built to provide a home for workers at the steel mill of George McMurtry. The mill has had six owners since its first, but still is working, despite the decline of the steel industry.

All of those features make Vandergrift a place where the past is a major part of the present. It makes it worth a visit to see that story.

1:30 p.m.

The Victorian Vandergrift Museum is in a school built in 1911 and, like many features of the town, is a work in progress.

With displays on three floors, it tells the story of the town in a number of ways. On the bottom floor is a room decorated with many pictures of initial work on the town along with map of the plans originated by the Olmsted firm.

If you’re lucky, you might run into Bill Hesketh, treasurer of the museum and historical society. He could tell you about McMurtry, owner of Apollo Iron & Steel, wanting to build a town that would attract workers and entice them to stay.

He would do that by having the famed designers draw up a plan for the ultimate company town. McMurtry thought a cultured worker was a good worker, so included plans for the Casino. He also saw the benefit of religious life, so provided $7,500 to any congregation planning to build a church costing $15,000 or more. He wanted sober workers, so the town was dry until 1936.

If you are lucky, Hesketh will be there to offer you some thoughts. But it will take some luck. He does not schedule tours or times he is there for visits. There are no other guides at the museum either. But simply wandering around the museum will provide a look at what Vandergrift is all about.

Victorian Vandergrift Museum, 184 Sherman Ave. Hours: 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Mondays to Saturdays. Details: 724-568-1990.

3 p.m.

Now, it’s time to take to the streets. In some ways, the rows of houses are the story of Vandergrift.

The look of the town is somewhat defined by the rows of company homes on streets that are devoid of 90-degree angles.

When the Olmsted designers laid out the plan, Hesketh says, they decided on 50-feet-wide lots, but McMurtry thought that was way too wide. He was selling the lots, and wanted to profit from them.

They became 25-feet-wide, leading to streets of homes generally built tightly together.

Hesketh points out some people eventually bought two homes and built them together to make one bigger residence. Or they bought one and tore it down to create a bigger yard. There are some properties that were sold as 50-feet-wide and are the sites of some nicer homes, for the non-laborer class.

Take a walk around and look at the history of a town as seen in its homes. The look of the town is created by the past and the gentle curves of the Olmsted design, which even creates a non-straight business district.

5:30 p.m.

After touring Vandergrift and getting ready for the finale of this day, it is time for dinner.

There are some likely stops for a meal in town, and these three win local praise. You probably saw them as you wandered around.

The G&G Restaurant (724-567-6139) on Columbia Avenue is largely a breakfast and lunch place, but is open till 9 p.m. for dinner.

A.J.’s Restaurant (724-568-2464) is open Tuesdays, Wednesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays until 10 p.m. and 11 p.m. Fridays.

Offering a more specific dinner outlook is the Steeltown Smokehouse (724-568-4087) on Washington Avenue. The burgers-and-wings emporium is open till 8 p.m. Mondays to Thursday, 9 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays and 6 p.m. Sundays.

7 p.m.

The best way to do this trip is to pay attention to the shows at the Casino, which can be checked out at www.casinotheater.org, then plan a visit on a day ending with some entertainment.

Make sure to arrive at the Casino with enough time to look around.

The oldest, active theater in Western Pennsylvania had become a unused shell when a group that became Casino Theatre & Restoration Management took it over in 1991, Hesketh says. They brought the site back to life.

Trumpet star Maynard Ferguson (1928-2006) performed there along with the Vogues and the Clarks. The renovated theater has been the home of stage presentations. Some of the restoration meant changes from the original, Hesketh says, but some of that provided aspects that seemed to be needed.

“This place just called for boxes,” he says, pointing to box seats on each side of the stage.

Roam around the Casino. The balcony casts a good and attractive view of the stage. The lobby, slightly smaller than what it once was, offers an attractive entrance.

McMurtry thought the Casino would be a significant part of the town when it was built in 1900.

It still is.

-

Old Pittsburgh Churches are a Sight to See

By Deborah Deasy, PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Monday, November 29, 2010t’s easy to overlook the oldest churches in Pittsburgh.

“Then, you come inside and see how beautiful it is,” says Sean O’Donnell, secretary at Smithfield United Church of Christ, one the city’s four oldest houses or worship.

The others — all soaring stone structures within blocks of each other — are the First Presbyterian Church and Trinity Cathedral, both on Sixth Avenue, and the First English Evangelical Lutheran Church on Grant Street.

One claims the grave of a Shawnee Indian chief. One has 13 Tiffany stained glass windows insured for $2 million. One boasts the world’s first architectural use of aluminum. One has a marble, wood and brass altar once exhibited at the Carnegie Museum of Art.

Each offers an oasis of quiet — at no charge — and sights to please even the most agnostic art lover. All offer free, informational brochures and tours upon request.

“These are real treasures for people to look at,” says the Rev. Catherine Brall, canon provost at Trinity Episcopal.

Visiting the churches helps one appreciate the city’s architectural history, along with “the depth of faith and piety that created these beautiful buildings,” says the Rev. David Gleason, senior pastor at First English Evangelical Lutheran Church.

On a recent Friday, the First Presbyterian Church wowed curious passers-by from Wyoming, Arizona, Ohio and Virginia.

“I think going to a church is a beautiful thing, regardless of your religion or politics. There are so many aspects that can be shared and appreciated,” says Morrison Simms of Jackson Hole, Wyo.

Simms’ companion — Stuart Herman of Scottsdale, Ariz. — believes a visit to such places helps couples discover and appreciate each other’s interests. “It opens dialogue,” he says.

Two of the churches — Trinity Cathedral and First Presbyterian — also offer sit-down eateries for weekday visitors. The Franktuary at 325 Oliver Ave. — under Trinity Cathedral — offers vegetarian, organic beef and gourmet hot dogs from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Mondays to Fridays. Our Daily Bread at 320 Sixth Ave. — under the First Presbyterian Church — serves hot lunches, soups, sandwiches and salads from 10:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Mondays to Fridays.

Trinity Cathedral (1872), Architect: Gordon W. Lloyd.

A plaque on the cathedral’s black iron fence describes the site as Pittsburgh’s “oldest unreconstructed landmark.”

Trinity Cathedral and the First Presbyterian Church share a former American Indian burial ground deeded by William Penn’s heirs to the congregations’ forefathers. French soldiers at Fort Duquesne (1754) and British soldiers at Fort Pitt (1758) also used the ground for burials.

Today, Trinity Cathedral maintains the last 128 marked graves of an estimated 4,000 people once buried on the site. The identified remains of many have been moved to other cemeteries. The unmarked bones of many others remain interred within a crypt in the sub-basement of First Presbyterian.

Prominent folks recorded on the present tombstones include Red Pole, principal chief of the Shawnee Indian nation, and Dr. Nathaniel Bedford, Pittsburgh’s first physician and a founder of the University of Pittsburgh.

Inside the cathedral, visitors will find hand-carved pews of white mahogany, a stone pulpit covered with intricate carvings of prophets, saints and bishops, plus, stained glass windows dating back to 1872.

Trinity Cathedral, 328 Sixth Ave., Downtown. Hours: 7 a.m. to 1 p.m. Sundays, 7 a.m. to 5 p.m. Mondays to Fridays, 9 a.m. to 1 p.m. Saturdays. Services available at 12:05 p.m. Mondays to Saturdays and 8:45 a.m. and 4:45 p.m. Mondays to Fridays, and 8 and 10:30 a.m. Sundays. Details: 412-232-6404 or here.

First English Evangelical Lutheran Church (1888), Architect: Andrew Peebles.

A 170-foot-spire distinguishes the First English Evangelical Lutheran Church, second oldest structure on Grant Street. Only nearby Allegheny County Courthouse & Jail is older.

Interior decorations include a contemporary cross by Virgil Cantini; the 500-square-foot “Good Shepherd” window of Tiffany Favrile glass, and a free-standing marble, brass and wood altar once displayed at the Carnegie Museum of Art.

Also notable is the “The Presentation of Our Lord in Temple” lunette, a shimmery glass mosaic and cloisonne work made in the late 1800s. It hangs high above the church’s permanent marble altar.

Newest additions to the landmark include a 100-drawer columbarium for the cremated remains of church members and friends of parish. “There’s enough room for 200 bodies,” says senior pastor Gleason. “It’s designed as a special reliquary. … These are the bones of our saints.”

First English Evangelical Lutheran Church, 615 Grant St., Uptown. Hours: 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. Mondays to Fridays; 8:30 to 12:30 p.m. Sundays. Services available 12:10 p.m. Mondays to Fridays, 8:30, 9:45 and 11 a.m. Sundays. Details: 412-471-8125 or here.

First Presbyterian Church (1903), Architect: Theophilus Parsons Chandler

Tiffany Studios designed 13 of the church’s 26-foot-by-7-foot stained glass windows, now insured for $2 million. All were hand-painted, making them unique among Tiffany windows.

“Each of the windows cost $3,000 when the building opened in 1905,” says Bob Loos, a deacon who gives tours. “As soon as you get a little sunlight coming in, they take off in brilliance.”

The Tiffany windows, however, are just a few of the 253 stained and leaded glass windows throughout the sandstone church.

Also notable are two 80-foot ceiling beams — each cut from 150-foot Oregonian oak trees — plus, a pair of rolling, two-ton, 30-foot oak doors in the sanctuary. “They operate on a track in the floor. … and are so perfectly balanced that one person can open or close each one,” reports the church’s free guide for visitors.

Visitors also will notice untold carved birds, animals and insects on the church’s interior stonework, including an eagle, butterfly and dove on the pulpit — representing the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

First Presbyterian Church, 320 Sixth Ave., Downtown. Hours: 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Mondays to Fridays, 9 a.m. to noon Sundays. Services available at 12:25 p.m. Tuesdays and 10:45 a.m. Sundays. Guided tours offered after the 10:45 a.m. Sunday service. Details: 412-471-3436 or here.

Smithfield United Church of Christ (1926), Architect: Henry Hornbostel

An airy, 80-foot aluminum steeple — supported by interior steel beams — marks the multilevel Smithfield United Church of Christ. It’s the sixth house of worship for the city’s first organized Christian congregation. The spire “has the distinction of being the first architectural use of aluminum in the world,” according the church’s Spire bulletin.

“The sanctuary reminds me of some of the big cathedrals in New York City,” says O’Donnell, the church secretary. “I was most taken by the plaster work.”

Interior features include a 19-foot rose window made in 1860, and 12 towering, stained-glass windows that illustrate Biblical scenes and Pittsburgh history, including an 1861 visit by President-elect Abraham Lincoln.

Smithfield United Church of Christ, 620 Smithfield St., Downtown. Hours: 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Mondays to Fridays; 9:45 a.m. to noon Sundays. Services available at 12:10 p.m. Wednesdays and 11 a.m. Sundays. Details: 412-281-1811 or here.

-

Woodville Plantation Offers Holiday Tours by Candlelight

Thursday, November 18, 2010Pittsburgh Post-GazetteThe Woodville Plantation living history museum will celebrate the holiday season in an 18th-century fashion with candlelight tours from noon to 8 p.m. Sunday at the historic site, 1375 Washington Pike, Collier.

Admission is $5 for adults and $3 for children ages 6-12.

The event will feature costumed guides, holiday displays and traditional decorations. Visitors will learn about holiday customs such as Twelfth Night, Boxing Day and the firing of the Christmas guns.

The full table feast celebrated during Twelfth Night will be displayed, and visitors will hear students of The Pittsburgh Music Academy perform musical selections throughout the day on a circa 1815 pianoforte.

A piece of Whiskey Rebellion history will be displayed — a flag that was once used by the whiskey rebels as a symbol of their resistance to the 1791 excise tax on whiskey.

The flag, owned by historian Claude Harkins and on loan to the Neville House Associates, is thought to be one of only two documented flags from the Whiskey Rebellion Insurrection of 1794.

Woodville Plantation, the home of John and Presley Neville, was built in 1775. It interprets life during the period of 1780-1820, the era of the New Republic. Guided tours of the house are available every Sunday from 1 to 4 p.m.

-

Abel Colley Tavern Helps Preserve Fayette County History

Sunday, November 14, 2010By Marylynne Pitz, Pittsburgh Post-GazetteUNIONTOWN — Five miles west of this Fayette County seat stands the Abel Colley Tavern, a red-brick beacon of hospitality to travelers along the National Road during the 1800s.

Just one mile from Searight’s Toll House, the tavern was known for its moderate prices and hearty clientele of wagoners, who swapped many a tale over Monongahela Rye in its barroom.

By this time next year, it will be a place for even more stories as it becomes the Fayette County Museum. With 6,500 square feet, the restored building will have office space on the second floor for the Fayette County Historical Society, which currently has no regular space to meet; its members often house artifacts in their homes.

The last people to live there, Sue and Frank Dulik, left the property to Virginia and Warren Dick, who donated it to the society.

Jeremy S. Burnworth, president of the Fayette County Historical Society, stands inside the front door of the former Abel Colley Tavern, which has been restored and will become the society's new home next year. Marylynne Pitz

Jeremy S. Burnworth, the society’s 31-year-old president, is a Markleysburg native who has developed a passion for Fayette County’s rich history. At a convention in September of the American Association of State and Local History, Mr. Burnworth got excited when he learned about standardized software made by the Rescarta Foundation in Wisconsin that allows historical societies to photograph, log and archive materials.

“What a perfect opportunity to do it right from day one,” he said.

An advisory committee will oversee the museum’s operation and at least 30 people have volunteered to help staff the museum and toll house. One of Fayette County’s best-known residents has also pitched in. At an opening ceremony in July, the temperature rose to 99 degrees in the 19th-century building. Joe Hardy, the 84 Lumber tycoon and former Fayette County commissioner, offered afterward to pay for a new heating and cooling system.

One person who knows the building well is Tom Buckelew, a retired physiology professor from California University of Pennsylvania. He figures he has spent 1,500 hours working on restoring the former tavern.

“It had been modernized with drop ceilings and acoustic tile ceilings,” Mr. Buckelew said, adding that many of the rooms had four or five layers of wallpaper that had to be stripped before repainting with period-appropriate colors.

Just inside the front door is a large foyer with a staircase. On the ceiling is some of Mr. Buckelew’s best craftsmanship — a hand-carved ceiling medallion that lends elegance to the new chandelier.

“I roughed out the medallion with a band saw and then just carved the rest. That was about two weeks, three hours a day,” he said.

On the second floor is a large ballroom where Mr. Buckelew painted an intricate, ruglike pattern of mustard, brick red and chocolate brown. It’s actually a centuries-old trick for disguising uneven floors.

“It was a way of capitalizing on bad design,” he said, adding that the front part of the ballroom is probably an inch lower than the back portion. “That was a feature that a lot of people adopted in the early 19th century. In lieu of rugs, you paint a rug on the floor.”

A team of inmates from SCI-Greene spent two weeks hanging dry wall in the building. A new ceiling was attached to a plaster-and-lathe one in the second-floor ballroom. Then, Mr. Buckelew put up crown molding with the help of another volunteer, Bill Zin. Joe Petrucci, a township supervisor in Menallen, donated 400 board feet of molding.

“That ceiling is tied to irregular joists. So the ceiling naturally has some dips in it, high spots and low spots,” Mr. Buckelew said, adding that the crown molding camouflages the dips.

The building, done in a vernacular Greek Revival style, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1995. Jerry Clouse, who nominated the building for federal designation, dates the structure to around 1835. He said two architectural features signify its use as a tavern: the kitchen ell with a double-stacked porch and two front doors, one of which opens into the barroom.

At least one historian believes it may have been a home much longer than it was a tavern. Ronald L. Michael, a retired anthropologist who excavated around the nearby Peter Colley Tavern in 1973, believes Abel Colley’s famous tavern stood on the opposite side of Route 40, partly because there was once a well on that property which would have provided water for travelers and horses.

Abel Colley owned a Fayette County tavern just outside of Uniontown on U.S. Route 40. Volunteers have restored the 19th-century building during the past year. The former tavern will become the Fayette County Museum next year and also will provide office space for the Fayette County Historical Society.

The building that locals know as the Abel Colley Tavern, Dr. Michael said, is more likely the house he built after making his fortune in the hospitality business, then retiring. Mr. Burnworth agrees but still treasures its history.

“It was probably only a tavern, if ever, for a very short period of time,” he said. “He died a few years after we believe it was built. Most likely, it was his home.”

-

Exhibit Celebrates the Many Styles of Homes in Beaver

Saturday, November 06, 2010By Marylynne Pitz, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

A model replica of the Agnew-Anderson House, built in 1808, is among the exhibits in "Bricks, Mortar and Charm," an exhibition at the Beaver Area Heritage Museum. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

BEAVER — Since 1802, this town 35 miles northwest of Pittsburgh has reflected the aspirations of the bankers, doctors, teachers, lawyers and politicians who inhabit its quaint streets and River Road, a lovely stretch of beautiful homes that overlooks the Ohio River.

Now, this community’s architectural aspirations are on view in a concise exhibition called “Two Hundred Years of Bricks, Mortar & Charm” at the Beaver Area Heritage Museum in downtown Beaver.

Local historians believe that a house built in 1805 and still standing at River Road and Market Street is the town’s oldest structure. Part of the home’s front section was built with hand-hewn logs that are still visible in the basement. The logs may have been salvaged from Fort McIntosh, a Revolutionary War structure built in 1778.

Edwards McLaughlin, left, and Mark Miner of the Beaver Area Heritage Museum take a look at "Bricks, Mortar and Charm," an exhibition that documents the architecture of Beaver. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

Edwards McLaughlin, chairman of the museum’s board of trustees, spent weeks photographing homes all over Beaver for the exhibition, which examines the evolution of design styles in 50-year periods. His volunteer work correlates to his day job because he’s a partner in the real estate firm Bovard Anderson and a fourth-generation owner of the business.

With its 19th-century-style street lights and restored storefronts, Beaver retains its Victorian-era look. So it’s no surprise that from 1850 to 1900, plenty of Colonial Revival, Queen Anne and other Victorian-period homes were built. There’s also a smattering of Italianate, Gothic Revival and Romanesque homes.

A replica log cabin is part of the Beaver Area Heritage Museum's permanent exhibit. Bob Donaldson / Post-Gazette

Surveyor Daniel Leet laid out Beaver, creating four squares in the center of town and four at its edge. Each one is named for a prominent resident or military leader. Agnew Square, for example, is named for Daniel Agnew, who was chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. At Third Street and College Avenue, an exact replica of the clock tower that adorned the 1877 courthouse stands on the southeast corner.

A new century dawned and tastes changed between 1900 and 1950. As a result, Beaver has examples of English Tudor, Craftsman bungalows and Art Deco designs. There are even examples of Prairie-style homes, a Frank Lloyd Wright design ideal that emphasizes an open floor plan, horizontal lines, shallow roofs with broad overhangs and banks of casement windows with art glass.

The exhibition features an excellent model of Beaver’s 1877 courthouse plus a replica of the Agnew Anderson House. Both were made by Robert A. Smith.

Mr. McLaughlin is just one of several hundred volunteers who combined their collective, considerable elbow grease to transform a former Pennsylvania & Lake Erie Railroad freight house into the Beaver Area Heritage Museum 12 years ago. The building was a shambles with holes in the ceiling, thick grime on the floors and a basement packed with old dust.

Now, the museum sparkles. There’s a permanent exhibition about the Beaver region, an outdoor vegetable and herb garden with native plants and an 1802 log house that’s a replica of a frontier home.

Mildred “Midge” Sefton, a retired home economics teacher, oversees the volunteers, who meet regularly on Thursday mornings in the basement to accession, catalog and log onto a database each artifact and document that is donated to the museum. Judy Reiners of Beaver recently finished compiling family documents that belonged to Adolf Mulheim, proprietor of a wallpaper and carpet store from around 1880 to the 1930s.

-

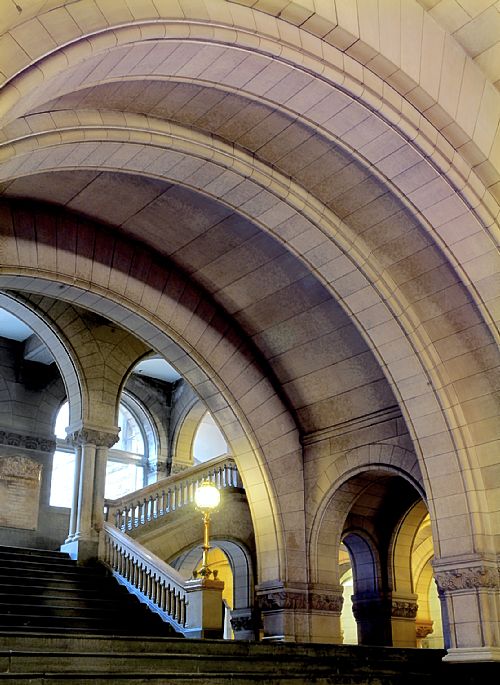

Courthouses Tower as Testaments to Our Pursuit of Justice, Desire to Document Memorable Moments

Thursday, November 04, 2010

By Janice Crompton, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

The dome inside the Washington County Courthouse, a building designed by Frederick J. Osterling. Bill Wade/Post-Gazette

The historic county courthouses of Western Pennsylvania are clearly more than mere buildings: Their walls bear witness to everything from birth to death.

They are, as Fayette County eloquently describes in a brochure, “… the scene of human drama, the repository of success and failure in life, the archive of the hopes and dreams of thousands.”

More than half of the courthouses of the 3,069 counties across the United States are recognized on the National Register of Historic Places, including five local ones: Allegheny, Butler, Fayette, Washington and Westmoreland.

This week, some of the courthouses, including those in Westmoreland and Beaver counties, took on a starring role as the official counting houses for Tuesday’s General Election.

Today, the majority of local county courthouses house the Common Pleas Court system and sometimes row offices, such as prothonotary, register of wills and clerk of courts. An exception is Allegheny County, which fused most row offices when voters approved a consolidation in 2005. The merger of the prothonotary, clerk of courts and register of wills offices formed the Department of Court Records, which is in the nearby City-County Building. But for the most part, the life-affirming and life-changing moments for each of us — births, marriages, home purchases and deaths — are recorded in a courthouse. And in the courthouse courtrooms, the drama of justice unfolds daily.

In addition, these buildings often honor and exhibit local history, such as the statue of the late Mayor Richard Caliguiri in Allegheny and the war memorials at the Washington and Beaver courthouses.

None of our local courthouses is an original. The first courthouses usually were primitive log cabins that gave way — often more than once — to grandiose architectural gems that have been rebuilt and reincarnated over the past two-plus centuries.

In his 2001 book, “County Courthouses of Pennsylvania,” Oliver P. Williams, a retired University of Pennsylvania political science professor, highlights each of Pennsylvania’s 67 courthouses. He visited each several times while doing his research.

In addition to providing details of architectural design, Dr. Williams examines the political climate and competitive atmosphere that led to the construction of some of the country’s finest monuments.

“I was always surprised how lavish public buildings were in the 19th century and how parsimonious they are now,” the 85-year-old said last week in a phone call from his home in Philadelphia. “There were plenty of tightwads in the 19th century, but the majority went the other way. Cities were in competition for growth and money.”

Before the interstate highway system was built, Dr. Williams traveled from Chicago to New York as a graduate student and he remembers seeing the tall spires of courthouses, beckoning travelers to visit their towns.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, courthouses typically were in the town square and the focus of local activity, he said. Trials there provided relief of boredom for spectators.

“Courtrooms were built like theaters,” Dr. Williams said. “They were big entertainment then.”

Several years ago, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court commissioned paintings of the state’s 67 county courthouses. Prints from those paintings are on display at the Pennsylvania Judicial Center, which opened in the summer of 2009 in Harrisburg.

Here’s a look at a half-dozen in our region:

Allegheny CountyThe Allegheny County Courthouse is “one of the most significant county courthouses in the United States from an architectural perspective,” Dr. Williams said.

Calling it “poetry in stone,” Dr. Williams wrote in his book that its beauty is an ideal example of Richardsonian Romanesque, an architectural style named for Henry Hobson Richardson, who believed, as his peers did, that the Allegheny County Courthouse was one of his crowning achievements.

“Richardson’s style was influential,” Dr. Williams said. “That courthouse was copied all over the nation.”

Mr. Richardson, also known for designing the Trinity Church in Boston, wanted to survive long enough to see the Allegheny County Courthouse completed, saying it was one of the works he wished to be judged by. He died, however, two years before it was finished in 1888.

The "bridge" looms over Ross Street and connects to Court of Common Pleas building, formerly to old Allegheny County Prison, to the Allegheny County Courthouse in Downtown Pittsburgh. It is still used to transport suspects to the "Bull Pen" to wait for their trials and hearings. Darrell Sapp/Post-Gazette

Primarily built from “Milford pinkish gray granite,” according to Dr. Williams’ book, the structure was designed with as many windows as possible, to provide natural lighting. The building’s 318-foot tower not only was symbolic but also served as a ventilation system, pulling in fresh air from above rather than the polluted air near street level.

The building also features four Norman towers with conical roofs along with moldings and ornamental stonework that were hand carved by 13 Americans and 13 Italians, according to literature provided by the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, which provides guided tours of the site.

“The thing that’s so extraordinary is the plan of the building,” said Albert Tannler, historical collections director for the foundation and author of a courthouse tour book. “It really is an amazing building.”

Possibly more impressive than the courthouse itself is the stone walkway, known as the “Bridge of Sighs,” that connects the courthouse to the jail, built at the same time and also designed by Mr. Richardson.

Patterned after the iconic bridge of the same name in Venice, the local bridge for decades provided a practical way to transport prisoners to and from the courthouse with minimal public contact.

Closed in 1995, the jail now serves as a family court center.

Beaver CountyLocated in Agnew Park in Beaver, the Beaver County Courthouse represents what Mr. Williams called “an architectural puzzle of a building.”

Concrete reliefs from the original Beaver County Courthouse now adorn the walls of the courtyard in the new courthouse, dedicated in January, 2003. Pam Panchak/Post-Gazette

Although it appears to be art moderne style, it contains unusual elements, such as a clock tower and a lunette, or crescent, window.

The eclectic mix is a result of a 1932 fire, which severely damaged the structure. Architects were able to salvage part of the burned 1875 courthouse, and they covered the new and old construction with a stone veneer, parts of which have been replaced over the years.

Butler CountyBuilt in 1885, the Butler County Courthouse has undergone several major alterations. Perhaps the most noticeable is the pointed stainless steel cap placed on its tower.

In his book, Mr. Williams explains how the shiny tower cap, which he calls “as durable as it is deforming,” was installed in 1958 after county commissioners found themselves unable to reject an offer of a free tower cap from Armco Steel.

The courthouse in Butler features a central clock tower with an elaborate cornice, a row of rosettes and arcaded corbels, or brackets, flanked by corner turrets, Mr. Williams said.

Gothic-arched windows on the first and second stories still have their stained-glass transoms.

Fayette CountyThe Fayette County courthouse is similar to the Richardsonian Romanesque style of the Allegheny County Courthouse, except it is smaller.

The gray sandstone courthouse in Uniontown features a 188-foot-tall central square tower, arcade windows and arched entryways. It also includes a “Bridge of Sighs” identical to the one in Allegheny County.

“Back in the day, that was the biggest compliment you could give an architect,” said Tammy Boyle, county human resources administrative assistant. “Today, you’d probably be sued.”

The design may have been borrowed from its neighbor to the north, but the structure is all Fayette County.

The stone was quarried locally, oak planks and panels were grown locally, and the iron for the building was rolled at a local mill. Even the brick used in the interior and for partition walls was made in the county.

The building has marble floors and iron stair railings, and the second-floor lobby contains four oval medallions, each 10 feet across, representing the county’s four leading industries at the time: coal mining, coke burning, agriculture and manufacturing.

While Ms. Boyle said the building is an architectural gem, it’s not without its drawbacks, especially when it comes to modern conveniences.

It’s no easy task to retrofit a historic building with wiring and security systems, not to mention plumbing and heating systems.

“There’s those days that we like it, and there’s those days when we don’t,” she said, speaking for county employees. “Sometimes in the winter it seems like we’re in Hades.”

Washington CountyWhen Debbie O’Dell Seneca was 13, she told her mother that she wanted to be a judge. She hadn’t yet laid eyes on the imposing sandstone and granite beaux-arts structure that is the Washington County Courthouse, but she never forgot the day she did.

“I was in complete awe,” she recalled. “It was like walking into a Roman cathedral.”

Today, she is Washington County president judge and she and others consider it an honor to work in the building, perched atop a large hill in Washington. It was built in 1900 and is crowned by a terra-cotta dome and statue of George Washington, both of which were recently refurbished.

Two 25-foot-high Italian Renaissance angels flanking the statue were removed when they began to deteriorate, but history buffs, including Judge O’Dell Seneca and county Commissioner J. Bracken Burns, have been pushing to have the angels restored.

Massive pilasters, Roman arches, Italian marble, bronze and highly polished brass grace the interior of the courthouse, which has a grand central stairway topped by a skylight.

Judge O’Dell Seneca said Architectural Digest in 1976 called it “one of the finest pieces of architecture in the United States.”

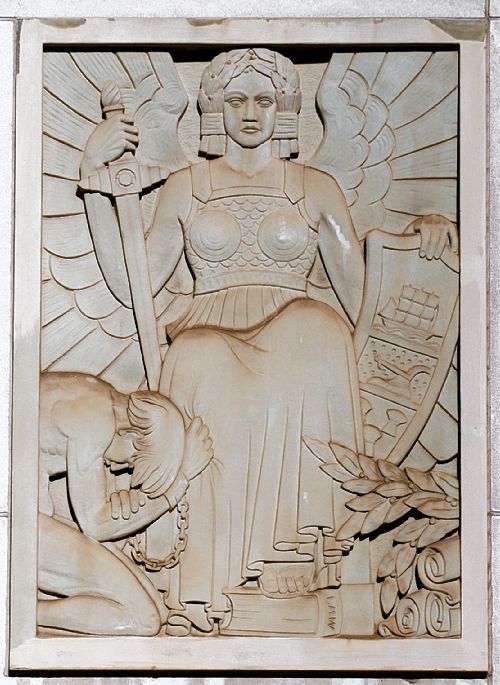

Westmoreland CountyAnother imposing and well-known beaux-arts style courthouse is in Greensburg.

Topped by a massive yellow-gold dome made of cast aluminum bronze over a rolled iron frame, the exterior is gray granite and “copiously decorated with the ornamental patterns learned at the Ecole des Beaux Arts,” Dr. Williams said.

The celebrated “Golden Dome,” as locals call it, is 175 feet above the sidewalk and arguably the signature piece on the county skyline.

Three arches grace the building’s entrance, framed by Corinthian pilasters, rosettes and bronze lamps. A marble staircase opens upward to twin spirals on the next floor. The structure contains marble walls in public halls, wall and ceiling murals, and a central rotunda that rises four stories to the domed ceiling.

The top of the building is graced by three female figures representing Justice, Guardian of the Law and Keeper of the Law — a fitting symbol for the courthouses themselves.