Category Archive: City Living

-

The Making of a Mural: Series of Coincidences Led to Collaboration Between Artist and North Side Homeowner

Saturday, January 15, 2011

By Kevin Kirkland, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Artist Ken Heusey in front of the mural he created for David McAnallen's renovated kitchen on the North Side. Pam Panchak / Post-Gazette

Life is sometimes like a movie script. Or maybe it just seems that way to Ken Heusey because he worked in Hollywood for 16 years.

Only in a movie would absentmindedly leaving your cell phone on a table in an airport restaurant lead to painting murals in a South Side restaurant and a restored North Side townhouse. The work has been a triumph and a treat for Mr. Heusey, an accomplished photographer and native of Fombell, Beaver County, who did fashion shoots and lighting on movie sets, including making Matt Damon look good in “Oceans 12.”

David McAnallen, who is finishing a nine-year renovation of an 1860s brick townhouse in the North Side’s Manchester neighborhood, is glad fate brought them together. No one else could have imagined and created the classical mural that draws your eyes up the moment you step into his kitchen.

“The collaboration with Ken was wonderful. As you walk around, you’re captivated. It sucks you in,” said Mr. McAnallen, a psychologist.

Mr. Heusey, 46, was heading back to Los Angeles a year-and-a-half ago when he stopped to eat at the T.G.I. Friday’s at the Pittsburgh International Airport and left his cell phone. Upon his return, he stopped in and asked to see the manager who was holding it for him. The server he spoke with recognized him — She was his 10th-grade date for the homecoming dance at Riverside High School.

That connection led to an introduction to the owners of Hofbrauhaus Pittsburgh on the South Side. Last fall, Mr. Heusey painted a large two-section mural of 19th-century barmaids and beer drinkers on the terrace overlooking the beer garden. He was finishing that project when he met Mr. McAnallen while the two men were working out at the North Side YMCA. When Mr. McAnallen saw his photos of the Hofbrauhaus project, he decided he’d found the artist to decorate his newly renovated kitchen.

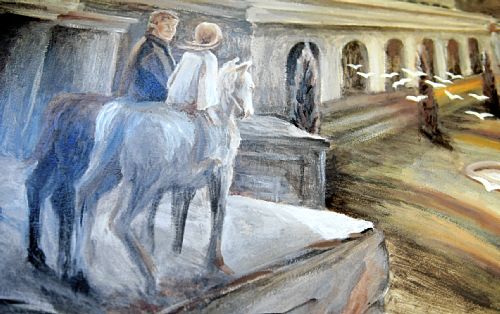

A detail from the mural Ken Heusey painted for David McAnallen's renovated kitchen. Pam Panchak / Post-Gazette

“I had thought about a mural before, but it never happened,” he recalled. “The space is so angular. I wanted to soften the angles.”

The space is an alcove around a new Velux skylight Mr. McAnallen added to the kitchen. Although Mr. Heusey had in mind a prominent spot visible from the doorway, it ended up closer to the ceiling, revealing itself gradually as a visitor enters the kitchen. The homeowner wanted something subtle.

“It was too big, too bold there,” Mr. Heusey agreed.

The artist suggested a trompe l’oeil painting in which old sandstone walls and a fragment of an old mural peek out from beneath layers of plaster. His inspiration for the classical scene came from a Gustave Dore engraving, “Isaiah’s Vision of the Destruction of Babylon.” He liked the mood of the drawing, especially the stormy sky. Mr. McAnallen liked it, too, but he asked the artist to take out the debris. He also added a pond similar to the one the homeowner had installed in his side yard. Isaiah was replaced with one horseman, then two.

“I like to create a story,” Mr. Heusey said, adding that he leaves the story’s details to the viewers’ imagination.

He copied the pattern of the faux stone corbeling beneath the scene from a nearby building and the carved lion’s face from an oak chair that is a McAnallen family heirloom.

Mr. Heusey spent about three weeks working on the painting, interrupted by the holidays. Before he started, he warned Mr. McAnallen that he would probably have concerns in the middle of the project, when he was still roughing in the design. He was right:

“I panicked only one time,” Mr. McAnallen admitted. “A lot of orange was coming through. I thought ‘Did I do the right thing?'”

David McAnallen at his home on Sheffield Street in Manchester on the North Side. Pam Panchak / Post-Gazette

The artist explained that the orange was underpainting and that it would not look that way in the final painting. And it doesn’t.

The two men declined to say what the project cost. Mr. Heusey, who spends about half of his time painting murals and the other half doing commercial photography, said his price depends upon the size, detail and complexity of the project. He says collaboration between artist and client yields a painting that pleases both.

“We let it evolve,” he said. “By going back and forth, we created something better.”

To contact Ken Heusey, call 310-963-6772 or go to www.khprod.com, which includes photos taken as he worked on the McAnallen project.

-

‘Location’ is Only Part of Marketing Downtown Homes

By Bob Karlovits, PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Sunday, January 9, 2011

The condos at Gateway Towers, Downtown, offers postcard-like views of PNC Park, Point State Park and the headwaters of the Ohio River. Joe Appel | Tribune-Review

Cindy Clifton stands at the corner of a condo in Gateway Towers overlooking postcard-like views of PNC Park, Point State Park and the headwaters of the Ohio River.

What sells this $1 million condo, like others that can be about $200,000 in the Downtown high-rise, is what has become a mantra of real estate sales, the building manager explains: “Location, location, location.”

But at the same time, she adds, the management of the building also recently spent about $80,000 to bring the lobby, hallways and other public spaces out of the 1950s. It is an attempt to make the building “hipper” and to compete with some other, newer residences.

The need to make a lobby more attractive, to have it “say” something, points to a twist in the marketing of Downtown’s places to live. The vertical lifestyle Downtown creates a different market than the lawns and properties of the suburbs. For many, that upkeep is the reason for leaving the suburbs.

Liz Caplan, real estate broker for Remax, says there is one requirement that is shared in all Downtown homes.

“People want a worry-free lifestyle,” she says. “They don’t want to worry about the garden or cutting grass. They want to be able to take off for a couple weeks in Florida without thinking about anything.”

Debbie Roberts, general manager of the Cork Factory apartments in the Strip District, says urban living is “not for everyone” and those who accept it also are lured by the features their building offers.

Frank Berceli, from the firm that handles leasing for the Heinz Lofts on the North Side, says those amenities are even more important than higher or lower rents or mortgages.

“If your dealing with a person who can afford $1,300 for rent, $50 more or less won’t matter,” he says. “But a good workout room will.”

Roberts says the Cork Factory thrives on amenities such as the picnic area, a marina and the building’s historic architecture

But, she adds, its closeness to Downtown also makes it attractive even if it is not right in the business district.

Similar comments are made at many Downtown residences, pointing to sales pitches that are far different from those for single-family homes.

Those pitches also point to how these buildings would seem to present different lifestyles, even if they seem similar.

It is all in what is offered

Both David Bishoff and Frank Berceli are big on privacy — but even that can take on a different nature.

Bishoff is president E.V. Bishoff Co., the Columbus, Ohio, firm that developed the Carlyle condos at Fourth Avenue and Wood Street. Berceli is general manager of Amore Management of Monroeville, which leases homes at the Heinz Lofts.

They both say they market their residences as offering a form of “privacy,” but Bishoff brags about how his “privacy” is amid bustle. Berceli’s, meanwhile, is in a suburb in the city.

Bishoff says one of the strongest aspects of the Carlyle is the 14 to 18 inches of concrete above and below condos and the walls that are lined with sound-deadening material. That makes the silence in the condos similar to that which residents experienced in their suburban homes before they moved Downtown.

“We don’t want to listen to our neighbor’s stereo,” he says of life in the condos, many of which cost about $300,000. “We did that in college, but we don’t want to do it now.”

Still, though, he adds, the Carlyle is in the middle of town, blocks from restaurants, shows, shops and health clubs. That gives it a location in the middle of activity that has lured many of its residents.

Berceli, on the other hand, says his clients tend to want to get away from urban life, but remain close enough to dip into it at a whim.

For that same reason, Berceli continues, the Heinz Lofts provide a better workout facility: it allows residents to stay at home instead of going to a commercial gym, no matter how close.

By living on the other side of the Allegheny River, the noise of traffic and business activity is gone. But the Downtown life is minutes away when it is wanted.

He says Heinz Lofts tenants are lured by that quiet as well as such features as the bicycle-hiking trail in front of it.

The ‘product’ is everything

William Gatti, president of Trek Development, which owns the Century Building on Seventh Avenue, Downtown, says the total “product” is the most important element in the marketing of a Downtown home.

Apartments there range from $600 a month rent-control units up to $1,500, and are being taken mostly by people who work Downtown or, in some cases, are retired but active as docents or other volunteer jobs.

“It puts people on the street,” he says. “They are out there going to work or going to restaurants. It is part of the whole urban lifestyle.”

He knows of some people who use Downtown residences as a part-time city home and suggests that strategy does not create a lively Downtown.

Brett Malky, a partner in 151 First Side, the upper-end condos on Fort Pitt Boulevard, says ultimately the “success” of all the Downtown residences is one of the best ways of marketing Downtown living.

“It is a lifestyle choice, but the fact that there are places appealing to young workers or empty nesters makes it possible to market Downtown living,” he says.

As he spoke, he was closing in on agreements that would leave only nine units available in the 82-place site that opened in 2007.

For condos that can top $1 million, that bespeaks the success he sees.

“With the small number left, it shows the fear of living Downtown is over,” he says.

-

Friendship May Get Aldi Grocery

Tuesday, January 11, 2011By Mark Belko, Pittsburgh Post-GazetteDiscount grocer Aldi appears to be headed to the East End as part of the redevelopment of a former car dealership.

Michigan-based Warner Pacific Properties is expected to brief the city planning commission today about its plans to convert the Day Automotive dealership into a grocery, offices and other retail uses.

The grocer in question is believed to be Aldi, although Leslie Peters, an attorney for Warner Pacific, said the developer did not yet have an agreement with any particular store.

Asked if Warner Pacific were talking to Aldi, Ms. Peters replied, “I think you can infer that.” City Councilman William Peduto, who represents the area, said Warner Pacific had stated that Aldi would be the grocer.

The developer is proposing an 18,000-square-foot grocery at the site at Baum Boulevard and Roup Street in Friendship. It is also planning 44,000 square feet of office space and 3,000 square feet of retail space.

Ms. Peters said Warner Pacific planned to keep the exterior intact.

The building, with a corner tower that once displayed pulsating light after dark, has some historic value. Built in the early 1930s as a Chrysler sales and service building, it remained as an auto dealership until it was closed in 2009 by the Day Automotive Group.

“We’ll be reusing the existing building,” Ms. Peters said. “We believe it’s a significant structure, at least for Pittsburghers. Everybody knows the building.”

She added that the developer did plan some interior renovations to upgrade the space. The total project cost is estimated at $4 million.

Because the property is a former auto dealership, Mr. Peduto said there are ramps within it that will allow for parking on the upper floors. The grocery will be on the first floor. He said an adjacent structure would be converted for office use.

Mr. Peduto said the project has the support of the Baum-Centre Initiative group. Through a community process, the developer is also addressing concerns about traffic patterns and other issues, he said.

After a planning commission briefing today, Warner Pacific is expected to appear before the city’s Zoning Board of Adjustment Thursday to request a special exception that would allow the property to be used for a grocery and office space.

Ms. Peters said the developer hoped to get all permits needed for the project by February or March and then start construction.

-

Owner Wants to Raze Iron City Building

Commission worries demolition will hamper future development at the historic Lawrenceville landmarkMonday, January 10, 2011By Diana Nelson Jones, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

The pipe shop portion of the closed Iron City Brewery is falling apart at the Lawrenceville landmark, on which the city has bestowed historic status. Bill Wade/Post-Gazette

Iron City Brewing Co. president Tim Hickman sounded urgent Dec. 1 when he asked the Historic Review Commission to let him tear down one of five buildings the city had granted historic status earlier in the year.

“The roof has collapsed,” he said, describing the original ice house in the former brewing complex in Lawrenceville. “The wooden I-beams have rotted and collapsed and the west wall is collapsing.”

Last week, the commission reconvened for a hearing, and Mr. Hickman was fighting to calm his agitation as the discussion drew out. A photo projected onto a screen showed twisted metal trusses hanging in a blue background — a rectangle of sky through the roof.

The brewing company had been cited by the Bureau of Building Inspection to abate the condition, which acting bureau chief John Jennings called “very dilapidated.” But the Historic Review Commission had a longer-term concern about the building, which dates to the 1890s.

And that concern is this: Would demolition of the old ice house prove to be a terrible mistake, jeopardizing a developer’s chances of getting a 20 percent tax break should this property become part of the National Register of Historic Places?

Although Mr. Hickman said a year ago that he embraced the historic status for the economic redevelopment possibilities, he told the commission last week he has not sought national status.

This raised some commissioners’ eyebrows.

Any future development project would almost assuredly depend on the tax credit, without which the company could be stuck with a white elephant.

“Is it your intention to seek tax credits to market this property?” acting chair Ernie Hogan asked him.

“We are still trying to determine that,” said Mr. Hickman, citing the company’s uncertainty over two other buildings that are unusable unless giant tanks can be removed from them. “If I can’t get them out,” he said, “who cares that it’s historic?”

The city approved historic designation for the complex of buildings in February, which automatically kept the company from dismantling any except for one that was exempted — a non-contributing 1970s rectangle. The company still has headquarters in the original building at 3340 Liberty Ave.

Mr. Hickman originally had wanted to demolish all but the headquarters, but preservation advocates seemed to have convinced him the complex was more valuable intact.

“We’re as concerned with the history as anybody in this town,” he said last week, “but if we lose a life, I don’t care about tax credits. I have security 24/7 running off copper thieves.”

As the owner, Mr. Hickman argued, shouldn’t it be up to him whether he wants tax credits?

Mr. Hogan said the commission is responsible for making sure historic buildings have available resources for preservation.

“If that demolition were to jeopardize the integrity of the assemblage, it could jeopardize any federal money to the site,” Mr. Hogan said. “[Mr. Hickman] would be turning his back on any public subsidies.

“I think this property is important. It could be eligible for federal transportation money [being on a bus route], sustainable communities grants, HUD money, all sorts of money.”

The Penn Brewery in Troy Hill was restored using federal tax credits, he said. Similar restoration “could be a huge economic driver” for the Lawrenceville portal.

Scott Doyle, grant manager for the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission in Harrisburg, said the determination of a building’s importance to an overall site “comes down to hardship or a level of significance.”

One way a building in a historic cluster could get a pass is “if it’s outside the period of significance for the property.” Other provisions exempt properties that “lack significance and do not occupy a major portion of the site, and if evidence is presented to show that retention is not economically feasible.”

The hardship provision applies “if a property is so deteriorated or altered that its integrity has been irretrievably lost,” he said.

In order to review the case, the PHMC would need a structural engineering report, photographs, historic documentation and cost estimates for repair.

The brewing company was a regional economic powerhouse in the late 19th and 20th centuries. Founded in 1861 as Frauenheim, Miller & Company, it brewed one of the country’s first golden lagers. It became the Pittsburgh Brewing Co. in 1899 in a merger of 20 regional breweries.

Among the brewery’s firsts were the snap-top can, the twist-off resealable bottle top, draft beer in cans, aluminum beer bottles and the original light beer, Mark V.

Brewing operations moved to Latrobe in summer 2009.

Last week, Mr. Hickman said he is “trying to embrace this process, but what’s the time limit? I have the city [building inspection] telling me you must do something, so I come here to do something and I’m told ‘Let’s wait.’ ”

The commission is expected to consider demolition in February, when an answer is expected about the building’s importance.

-

Historic Panel Gives a Reprieve to Igloo

Thursday, January 06, 2011By Mark Belko, Pittsburgh Post-GazetteThe Civic Arena has won a bit of a lifeline.

A bid to protect the 49-year-old landmark from demolition got a boost Wednesday when the city’s historic review commission gave preliminary approval to its nomination as a city historic structure.

The 5-1 vote clears the way for a formal hearing Feb. 2 on the proposed designation, one opposed by the Pittsburgh Penguins and the arena’s owner, the city-Allegheny County Sports & Exhibition Authority. John Jennings, acting chief of the city’s Bureau of Building Inspection, cast the no vote.

Even as it gave preliminary approval, the commission stated that the decision was not a determination on the merits of the application for historic status filed by Hill District resident Eloise McDonald.

In fact, nine years ago, the commission gave preliminary approval to the arena’s designation as a historic structure only to reject it in a final vote.

Nonetheless, Ms. McDonald said afterward that she was thinking “very positive” on the chances of getting a final vote in favor of the nomination. But she added it could be a tough sell since Mayor Luke Ravenstahl, who appoints historic review commission members, favors demolition.

“I’m going to stay optimistic to the final decision,” she said. “But like I said, I know the politics of the game.”

However, Ernie Hogan, the commission’s acting chair, said afterward that the mayor is “not telling us what decision to make” on the nomination.

“We have a charter to uphold regarding preservation standards. That’s all he’s saying, do your job,” Mr. Hogan said.

In arguing the case for the nomination, Ms. McDonald said the arena, with its retractable roof, is unique.

To tear it down would be “just awful,” she said. “There’s a lot of young kids, if they would ever see that dome open, there would be a whole lot more support for it. If you’ve never seen it open, you have no idea how extravagant and beautiful it is.”

The preliminary finding is a setback for the SEA and the Penguins, who have the development rights to the land that includes the arena. The team wants to demolish the structure to make way for a residential, office and commercial development.

Travis Williams, the Penguins’ senior vice president of business affairs and general counsel, declined comment on Wednesday’s decision.

But Shawn Gallagher, an attorney for the SEA, said the agency does not believe the Igloo meets the criteria for historic status. Describing Ms. McDonald’s nomination as “frivolous,” he said the same criteria used to nominate the arena eight years ago — and rejected — is being used this time.

And while Ms. McDonald spoke of the marvel of the retractable roof, Mr. Gallagher said it “never really worked” and doesn’t work anymore.

“It’s not worthy of preservation,” he said of the arena, adding it is costing the SEA and taxpayers about $65,000 a month to maintain it.

The Penguins moved from the arena to the Consol Energy Center across the street last summer.

Scott Leib, president of Preservation Pittsburgh, noted that state preservation officials have determined that the building is eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

“We’re not trying to obstruct progress. We just have a totally different view of what progress is,” he said.

Wednesday’s vote prevents the SEA from demolishing the structure until a final determination is made on its status. However, the agency did not plan to start the razing until spring at the earliest.

Once the historic review commission has completed its work, the nomination must be considered by the city planning commission and city council before the arena’s final fate is known.

-

Steelpan City

Pittsburgh City Paper

For the Week of 01.05.2011 / 01.12.2011

BY ANDREW MOORE

Jonnet Solomon-Nowlin - Steelpan Drum Instructor, owner of The National Opera House in Lincoln-Lemington - Brian Kaldorf

A local woman is hoping that the sounds of steelpan drums can revitalize one of the city’s most historic homes and the lives of young people.

The National Opera House, located on the border of Homewood and Lincoln-Lemington — and once the home of the National Negro Opera Company — has sat vacant for years. But now Jonnet Solomon-Nowlin, the building’s owner, believes her family’s U.S. Steelpan Academy can add value and structure to young lives, while bringing attention to the neighborhood’s often-overlooked past.

Steelpan drums were invented in the Caribbean — in countries like Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago — during the 1930s. Steelpans were originally crafted from discarded 55-gallon oil drums. To achieve their signature pitched sound, two rubber-tipped mallets strike the surface of the pan, where notes have been marked onto the stretched steel surface.

Starting at the age of 14, Solomon-Nowlin’s father, Phil Solomon, founded several steelbands in Guyana; he was named Musician of the Year in 1971. After moving to Pittsburgh in 1984, he founded Solomon Steelpan Company and began manufacturing steel drums for organizations throughout the country. Solomon was the first manufacturer of steelpans in Pittsburgh.

After dedicating years to this instrument, Solomon wants the next generation to take over.

“The whole idea of the academy,” he says, “is to launch the steelpan into the 21st century, for me to pass this knowledge on to younger people.”

Solomon-Nowlin hopes not only to pass on that knowledge, but to teach young people a skill that can add value to their community.

“I would like to see steelpan and the arts and music help young people,” Solomon-Nowlin says, “by giving them an opportunity to express themselves through art.”

While she’s working to restore the Opera House, for the past several years Solomon-Nowlin has been able to teach lessons through community partnerships. And when she begins a new series of classes at the East End’s Union Project this month, it will be a step closer to running the academy within the National Opera House.

The Union Project lessons are important, she says, “and the first set of students will be a marketing piece for the house.”

Using the house as the home base for the Steelpan Academy makes sense. After all, the building has always had a role in the emerging African-American art scene, especially during the previous century.

The three-story Victorian home sits on a terrace overlooking Homewood. Built in the Queen Anne style in 1894, it was home to many prominent black Pittsburghers over the years, including Roberto Clemente, Lena Horne and Woogie Harris, brother of famed photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris.

But its most significant tenant was Mary Cardwell Dawson’s National Negro Opera Company. Launched in 1941, the NNOC was the first African-American opera company in the country. The NNOC held productions for 21 years and traveled to Washington, D.C., New York City and Chicago.

Solomon-Nowlin says she learned about this history through the advocacy efforts of the Young Preservationists Association of Pittsburgh (YPA) and the group’s executive director, Dan Holland.

The YPA is a preservation group that encourages young people to be involved in researching, documenting and eventually restoring historic places. Once a year, the organization releases a Top Ten list of the best opportunities for preservation in the region. In 2003, the Opera House was on that list.

“Their Top Ten list and the education around it, and why it’s important to preserve,” Solomon-Nowlin says, “is one of the key things that brought awareness to the project. They were able to reach a lot of people.”

And that’s what Solomon-Nowlin is hoping to do with Steelpan.

The Young Men and Women’s African Heritage Association, headquartered on Pittsburgh’s North Side, has been teaching steelpan for 15 years, and the Solomon family has been involved since the beginning. Lessons were first taught by Phil Solomon and later his daughters, Janera and then Jonnet. Jonnet gives lessons on Saturdays at the New Hazlett Theatre.

Janice Parks, executive director of the heritage association, says the steelpan is a good fit for her students.

“It’s an easily accessible instrument,” Parks says. “You don’t have to have years and years of experience to be great. [Students] can pick up two mallets and an hour later they can play the melody line of a tune that’s familiar to them.”

Adam Warble, an instructor at the academy, agrees, and says “it’s definitely a popular instrument — it’s fun.” Warble says that his young students get particularly excited when he mentions current hip-hop songs that feature steelpan. But Phil Solomon stresses the versatility of the instrument. “Steelpan was actually created to play classical music,” he says.

Parks says her students learn to play everything from “Bach and Beethoven to Stevie Wonder.”

When the academy begins teaching at the Opera House, Warble thinks it will be “absolutely wonderful. Especially since the steelpan was invented in the Caribbean” — where the culture is heavily influenced by the African diaspora. “[And] since [the home] was a hub of African-American cultures, I think it’s wonderful to bring that back to the Opera House.”

The next step is bringing back the house itself. Solomon-Nowlin has recently hired grant-writers to find funding for the home’s restoration. Architects, electricians and carpenters have all agreed to work with her, and some have already donated time to the project.

Now, she just needs to raise enough money to begin the restoration, and to begin turning the Opera House back into a home for music. But she’s quick to point out that because her forte is music, she can use all the help she can get on the restoration side of this dream.

“I’m not in the preservation business,” she says with a laugh, “I’m just in it by default. My key thing is to just make sure it’s preserved. We really have to push forward.”

-

Some in Carrick Strive to Save Victorian House

Friday, December 24, 2010By Diana Nelson Jones, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

Julia Tomasic of the Carrick-Overbrook Historical Society is trying to save the last great Victorian home in Carrick, at 1425 Brownsville Road, by nominating it for historic status. Bob Donaldson/Post-Gazette

At one corner of Brownsville Road and The Boulevard in Carrick sits state Rep. Harry Readshaw’s funeral home. Across The Boulevard, a late-19th-century Queen Anne house is the last of the grand Victorians remaining on the main drag.

Its owners want to sell and may have a buyer in Mr. Readshaw, who said he is interested in buying the property and that demolishing it to provide parking “might be a decision to be considered.”

Mr. Readshaw’s interest has spurred the Carrick-Overbrook Historical Society to try to save the house.

Historical society member John Rudiak documented the property and this week nominated it for historical designation. He said demolition of the house would put an end to any evidence of Carrick’s Victorian heritage.

The nomination would stall any plan to demolish the house until the Historic Review Commission could determine whether it is eligible, based on a set of federal criteria. Eligibility ultimately must be decided by Pittsburgh City Council. Historic status regulates changes to a building’s exterior but not to its interior.

Richard C. Gasior, whose wife’s family has owned the four-bedroom home since 1952, said the family needs to sell it and has been advised that $150,000 would be a fair price. “If I can’t get anybody to buy it, I’m going to go with Readshaw,” he said.

Known as the Wigman House, it was built in the late 1800s by William Wigman, owner of Wigman Lumber on the South Side. The nomination states that it is “the last remaining example of several homes of the wealthy South Side gentry who lived in Carrick.”

The current owners gave a tour to members of the Carrick-Overbrook Historical Society several weeks ago, said Julia Tomasic, a founding member of the society.

“We’d love to buy it, but there are just three of us” in the society, which has no money, Ms. Tomasic said. “It has a brand-new furnace, a slate roof and the interior woodwork and walls in original hardwood, with six fireplaces, including one converted for wood. Nothing has been done to alter it.”

According to the Pittsburgh code for historic preservation, a property must meet at least one of 10 criteria to be eligible for preservation.

The nomination papers cite several possible eligibilities. One is that the home, a classic American Queen Anne, has not been modified. Its features include an asymmetrical facade, front-facing gable, overhanging eaves, polygonal tower, shaped and Dutch gables, a porch covering part or all of the front facade, a second-story porch or balconies, pedimented porches, dentils, spindles, differing wall textures including fish scales, and oriel and bay windows.

“We heard rumors for a year that Harry [Readshaw] would buy it to tear it down, and we thought it was a joke because we consider Harry a friend of the neighborhood,” Ms. Tomasic said. “Parking? You park on the street. We’re city people.”

“It’s not like I’m sitting here champing at the bit with a sledge hammer,” Mr. Readshaw, D-Carrick, said, “but business is business and any business is looking to improve its services.”

“And if we don’t get it, what happens to it?” he said. “Somebody dying to live in a big Victorian who would be a wonderful neighbor would be a positive.” A Section 8 landlord is a more likely prospect, he said, adding, “The 29th Ward has been inundated with Section 8 housing.”

Brownsville Road once had several grand Victorian homes owned by prominent businessmen. As a hilltop neighborhood, Carrick was a refuge from the smoky city. Through much of the 20th century, it was solidly middle class and owner-occupied. It remains so, but some of its stability is eroding.

In its argument for historic status, the historical society calls the Wigman House the most prominent home in Carrick, “our crown jewel Victorian.” Losing it would be a shock, the document reads, and “one more loss that we cannot sustain.”

-

Downtown Honus Wagner Store has Finally Struck Out

A sporting goods fixture for 93 yearsWednesday, January 05, 2011By Mark Belko, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

The Honus Wagner Sporting Goods store on Forbes Avenue is closing after 93 years in business Downtown. Michael Henninger/Post-Gazette

First it was Gimbels, then Joseph Horne, Kaufmann’s and Candy-Rama. Now another iconic Pittsburgh retailer is preparing to fade from the scene.

After 93 years Downtown, Honus Wagner Co. sporting goods store plans to close its doors permanently within the next six weeks after a going-out-of-business sale.

Harriet Shapiro, who co-owns the store with her husband, Murray, said Tuesday that the family, after four generations of ownership, simply had no one left to take over the reins.

“We’re very sad to see it go. It’s been a Pittsburgh landmark for so many years,” she said.

While word of the closing filtered out Tuesday, the clock has been ticking on the store for some time. In 2009, Point Park University reached an agreement with the owners on an option to purchase the property as part of its plan to move the Pittsburgh Playhouse Downtown.

Under terms of the agreement, the university had the right to take over the property once the Shapiros vacate it or in four years, whichever came first.

Mrs. Shapiro said she and her husband had considered selling the store but were unable to find anyone with an interest in purchasing it.

She said the store was not closing because of poor business.

“Absolutely not,” she declared. “It’s a closing sale. It’s not a desperation sale or a bankruptcy sale or anything like that.”

Opened in 1918 by the legendary Honus Wagner, the Hall of Fame shortstop for the Pirates, the store has been a sports fans oasis Downtown for decades, jam-packed to the rafters with jerseys, jackets, T-shirts, tennis shoes and other merchandise.

At one time, the store also supplied uniforms for the Pittsburgh Pirates as well as semipro and high school teams in the region.

The Shapiros purchased the store from Mr. Wagner about 1928. The shop first was housed on Liberty Avenue but moved to its current location on Forbes Avenue nearly 60 years ago.

On Tuesday, the store with the black-and-gold awning and sign (what else?) was closed for inventory, but will reopen today for its final days.

Patrons were saddened to hear about its demise.

Ron Gruendl, spokesman for BNY Mellon Downtown, said he still had a Frank Robinson model baseball bat he bought at the store in the mid-1960s.

“For many people who grew up and came into the city during the baby boom era, we’re losing part of our childhood,” he said. “Before there was Dick’s [Sporting Goods], before there was anything, it was Honus Wagner. Honus Wagner and Chatham Sports, those were the places.”

David Vance, a former Pittsburgher who now lives in Hudson, Quebec, just outside of Montreal, remembers driving to the store with a friend to pick up their first Little League uniforms.

“Along with standing out in the right field [seats] section of Forbes Field hoping to catch a home run and see [Roberto] Clemente up close, that visit to Honus Wagner was a cherished memory of my youth. It will be missed,” he wrote in an e-mail.

The closing likely will be a boost for Ace Athletic, a sporting goods store that opened on Forbes a short distance from Honus Wagner in September. Manager Tim Piett, however, found no joy Tuesday in knowing that the old store was closing.

“I worked there 27 years,” he said. “I was very close to the family. They’re very good people.”

The store will eventually be reborn as a performing arts center. Point Park intends to use it and several adjacent properties it owns to relocate the Pittsburgh Playhouse from Oakland to Downtown. The new complex would feature three theaters ranging from 150 to 500 seats each, production and teaching areas, a residence hall and retail space.

University spokeswoman Mary Ellen Solomon said the move wouldn’t occur until the second phase of the school’s academic village initiative Downtown and that that was still “several years down the road.”

For some, though, the promise of new development did little to soothe the pain of seeing another local landmark disappear.

“It’s sad. It’s a long-standing store in Pittsburgh. Downtown is getting empty,” said Brenda Lane of Scott, who stopped at the store Tuesday, hoping to purchase a Winter Classic T-shirt. “All our retail places are going by the wayside.”