Author Archives: ryochum

-

Historic Pittsburgh Home Bears Benign Swastika

By Bob Bauder

PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Sunday, October 31, 2010

Thelma J. Smith's home on Andover Terrace in the Upper Hill District bears a swastika in concrete above the entrance. Before fascism, the swastika was viewed as a good-luck symbol. Justin Merriman | Tribune-Review

Thelma J. Smith and her late husband faced a moral dilemma nearly 30 years ago: As black Americans, they had to decide whether they wanted a universal symbol of hate to remain imprinted on the front of their historic Hill District home.

The swastika was covered for decades by previous owners, and no one in the neighborhood, not even the Smiths until after they bought the house, knew it was there.

Thelma Smith thought of the Jewish neighbors, Holocaust survivors with concentration camp numbers tattooed on their arms.

What would they say? she asked herself.

More importantly, what would people in the community say?

The Smiths researched the subject. What they found, combined with what they knew about the house, swayed them.

The swastika predates Nazis by thousands of years. Before fascism, it was viewed as a good-luck symbol. The one in question was an original feature on a house that was then about 69 years old, the second-oldest home on an old street.

Smith, 72, had to explain all of that to the Jewish neighbors, who came to her upset but later agreed the swastika in this case is benign. It differs from the Nazi symbol in that it is not positioned at an angle.

“I just felt it was important historically to keep it,” Smith said.

A photo from 1912 shows the builder (Lindermer at far right) of Smith's home, which was built in 1912 for Herman S. Davis, who christened his home "Swastika." Justin Merriman | Tribune-Review

The house on Andover Place was built in 1912 for Herman S. Davis, who christened his new home “Swastika,” according to a photograph album that Smith inherited from previous owners and the March 1913 issue of Concrete-Cement Age magazine, which featured a story on the house.

Davis, whom Concrete-Cement Age identifies as a consulting engineer and astronomer, had his house built of poured concrete, a new architectural technique at the turn of the last century. He had the swastika, which Thelma Smith estimated is two feet square, imprinted in a prominent location on an exterior wall facing the street. Nobody knows why.

The house has 13 rooms and 48 windows. It is the only house in the region known to have a swastika as a design feature, according to representatives of Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

Thelma Smith said the swastika was covered by wood when they bought the house in 1976. About 1981, they had the concrete cleaned and the wood removed.

Ever since, the house has been a conversation piece and curiosity for people traveling the narrow, tree-lined street. The house is technically in the Upper Hill, but it’s on the last street before Schenley Farms Historic District. It seems secluded with its large trees, empty lots on either side and a steep hill in back rising about 60 feet to Dakota Street.

"I just felt it was important historically to keep it," Thelma J. Smith said of the swastika imprinted on her home. Justin Merriman | Tribune-Review

Numerous people stopped over the years to ask Smith and her family about the swastika. Cars slow down as they pass. Smith said police officers patrolling at night have shined spotlights on the swastika, presumably for new officers to see.

The family doesn’t mind the attention, but an event in May was a bit much. Somebody came in the middle of the night and attempted to cover the swastika with cement. Smith’s youngest son, Lee, noticed it and found imprints from a ladder in the yard.

His mother, who didn’t hear anything that night — probably because of the thick concrete walls — suspects a student prank. The University of Pittsburgh campus is just down the street. She said the kids probably were scared away before completing the job, which would explain why the swastika was partially filled in.

“They needed to be scared if I would have caught them,” said Lee Smith, 35, a Pittsburgh City Football League most valuable player for Schenley High during the 1990s and still in good shape.

He said a run-in with his father, Donald L. Smith, who died in September, would have been worse. In his younger days, Donald “Toro” Smith was a professional heavyweight boxer, who once fought Joe Frazier before Frazier became world champion.

The family cleaned out the cement without damage to the swastika.

There it remains for all to see, just as Herman S. Davis intended. And there it will stay, as far as Lee Smith is concerned.

Smith intends to buy the house in December from his mother. He said she can live there with him for the rest of her life. That suits his mother just fine.

“I always loved this street,” she said. “It’s country living in the city.”

-

Counties Seek Funds to Refurbish Mon River Ferry

Friday, November 05, 2010Pittsburgh Post-GazetteThe Washington County Commissioners have approved a $971,000 federal grant application to refurbish the Fredericktown Ferry, better known as Fred, which links two tiny towns separated by the Monongahela River.

Fayette County officials signed off on the application last year.

The Port of Pittsburgh Commission recommended repairing the cable driven ferry that shuttles vehicles and passengers across 800 feet of the river between Fredericktown, Washington County, and LaBelle in Fayette County.

The three- to four-minute trip saves motorists from driving about 16 miles to the nearest bridge.

The 60-foot-steel boat can carry six vehicles per trip, and transports about 500 each day.

-

Setback Won’t Deter Move of Historic House

Friday, November 05, 2010By Len Barcousky, Pittsburgh Post-GazettePaul Orange hasn’t given up hope that he will be able to buy and relocate the historic William Smith House in Mercersburg, despite a setback Thursday.

The house is on land owned by the MMP&W Volunteer Fire Co., which acquired the property in 2009 with plans to expand its aging facilities.

The board that oversees the regional fire company opened bids on Thursday for demolishing the 260-year-old structure but did not consider a proposal from Dr. Orange to move it.

Contacted after the meeting, Dr. Orange said he was advised that his offer to pay the fire company $100 for the building, rather than charge for tearing it down, had not been submitted in the right form.

The fire board, however, took no action on the demolition bids it received during its 15-minute meeting. That decision gives him hope that he still can reach an agreement to preserve the house, he said.

Joel Bradnick, a spokesman for the fire board, said the five bids would be forwarded to the fire company’s engineer for evaluation. He described Dr. Orange’s offer as a nonbinding “one-line memo.”

The low bid for demolition was $18,000.

“But why pay $18,000 to knock something down when you have someone willing to give them money to take it away,” Dr. Orange said.

The fire station and the Smith House are next to each other on Mercersburg’s Main Street.

If he is able to reach an agreement to move the house — either with the fire company or with the firm chosen to do the demolition — the next likely step would be to acquire a new location nearby. One possibility is a lot on the other side of Main Street, the site of a closed gas station.

Relocation and land acquisition could cost him as much as $100,000.

The Smith House was built in the 1750s. Constructed as a one-story cottage, it was greatly modified in the 19th and 20th centuries with the addition of a second story and porches.

News that the Smith House might be demolished attracted the interest of a museum in Northern Ireland. The Ulster American Folk Park has been developing plans to rescue the 18th-century first floor of the structure and move it to Europe. There it would become part of a collection of buildings with ties to Scotch-Irish immigration history. Several structures at the outdoor museum were moved from their original sites in southwestern Pennsylvania.

Worries about demolition also resulted in the formation of a small citizens group called the Committee to Save the William Smith House. Committee members have thrown their support behind Dr. Orange’s efforts to move the building.

“I hope we all can come together in a goodwill effort to restore this important piece of history,” said Karen Ramsburg, president of the Smith House committee. “This is America’s house, and I think it could become a real tourism magnet near the Interstate 81 corridor.”

Mercersburg is about 150 miles southeast of Pittsburgh. It is about 10 miles west of the Greencastle exit of I-81.

William Smith, an 18th-century businessman and local magistrate, was one of the leaders of what historians describe as the earliest organized opposition to British rule of its American colonies.

His home was a meeting place in 1765 for mostly Scotch-Irish settlers who organized themselves into armed bands. They formed a local militia after concluding that neither the Quaker-dominated colonial government in Philadelphia nor British officials in London were able to protect them from Indian raids.

William Smith’s brother-in-law, James Smith, was the leader of a group of settlers known as the “Black Boys,” who disguised themselves with paint and Indian clothes. Armed and angry, the Black Boys stopped pack trains traveling from Philadelphia to Fort Pitt that they believed were carrying weapons and ammunition that would end up in the hands of their Native American enemies.

After the British sent troops to nearby Fort Loudon to protect the traders and arrest the Black Boys, the soldiers twice found themselves besieged by the frontier militia.

The shots fired in 1765, 10 years before the Battles of Lexington and Concord, could be called the opening shots of the American Revolution, supporters of the Smith House say.

Dr. Orange describes himself as a history buff. A Westmoreland County native, he is a graduate of Greensburg Central Catholic High School and Saint Vincent College. He has a family medical practice on Route 30, east of Chambersburg.

-

Historic Designation Urged for Rest of Fineview Incline

By Tony LaRussa

PITTSBURGH TRIBUNE-REVIEW

Thursday, November 4, 2010

Bill Weis of Fineview walks Wednesday along the old wall that remains of the old Nunnery Hill Incline, which ran from 1887-89. Jasmine Goldband | Tribune-Review

As local historic landmarks go, the red-brick building and soot-streaked stone retaining wall that runs several hundred yards along Henderson Street in the North Side give little indication of their importance to Pittsburgh’s past.

Trees, shrubs and weeds have pushed their way through joints of the wall’s cut sandstone blocks, and sections lean precariously under the weight of the hillside rising above.

The walls and building along Federal Street are remnants of an incline that curved 70 degrees and ferried riders up and down the hillside between old Allegheny City and Nunnery Hill. The neighborhood perched on the hill behind Allegheny General Hospital was named for Flemish nuns who ran a school for girls there in the 1830s. It became Fineview.

“What’s left of the incline, which ran from 1887 to 1899, is a part of Fineview’s history that’s worth saving,” said Ed Lewis, director of Fineview Citizens Council. “We consider this a community asset that can be utilized in our long-range plan to create an inviting gateway to the neighborhood.”

On Wednesday, the city’s Historic Review Commission agreed.

In a 4-2 vote, the commission recommended that Pittsburgh City Council designate the structures as historic landmarks. Commissioners Linda McClellan and John Jennings voted against the nomination.

The incline was designed by prominent civil engineer Samuel Diescher, who designed the Duquesne Incline and the machinery for the Ferris wheel.

The building at the corner of Federal and Henderson was the incline’s base station but was not part of the original petition seeking historic preservation. Commissioners thought it was important to preserve the structure and the wall.

The building’s owner, Jonathan Shepherd, does not have to agree to a historic preservation designation for the process to proceed. He could not be reached.

“In the long run, I think the historic designation will be a benefit to the community and the owner of the property, especially with all the development that’s occurring along Federal Street,” said Walt Spak, vice president of the citizens council.

“And if there are any ways we can help the owner by obtaining grants or whatever is available to make improvements, we’ll be behind him,” he said.

A historic designation means property owners must obtain commission approval before making changes to the exterior.

Bill Weis, who grew up in Fineview and is a citizens council board member, said preserving the structures is a “big first step.”

“When we were kids, we used to play up where the tracks were located,” said Weis, 63. “It was deteriorating then and has only gotten worse. So if we’re going to save it, now is the time.”

-

Civic Arena Seats, Other Items Up for Sale or Bid

Thursday, November 04, 2010By Mark Belko, Pittsburgh Post-GazetteFans will have a chance to buy seats and other memorabilia from the Civic Arena over the next two months through on-line sales.

The city-Allegheny County Sports & Exhibition Authority approved an agreement this morning with the Penguins related to the sale of assets from the Igloo, which closed at the end of July.

Seats from the arena will go on sale to Penguin season ticket holders in the next few days, a sale that will run until Nov. 30. That will be followed by a sale to the general public on Dec. 1. A pair of seats will cost $495. Buyers can choose from red, blue, black and, of course, orange seats, but they will not be able to request individual seat numbers. About 5,000 seat pairs will be available for purchase.

The seat sale will be followed by an online auction Dec. 8 for other arena memorabilia, some of which will include Penguins logos or the signatures of players.

Bidding for the memorabilia will start about two weeks before Dec. 8. The highest bidder will be awarded the items. Those who have placed a bid will be notified if they have been outbid leading up to the closing Dec. 8.

“Although I don’t like this phrase, it’s very similar to eBay,” said Shawn Allen, chief operating officer for AssetNation, which is handling the sale.

The first online auction will be on Nov. 17 for arena furniture.

All of the seat transactions will take place on www.iglooseats.com

Bidding will be conducted at www.asset-auctions.com

Those who don’t have access to the Internet can call 1-800-303-6511 for a paper bid form.

The sale is expected to generate $1.6 million for the SEA and $800,000 for the Penguins, who will donate their share to their foundation.

The SEA’s share ultimately could be used to help pay for the demolition of the iconic 49-year-old domed building to make way for redevelopment.

-

Courthouses Tower as Testaments to Our Pursuit of Justice, Desire to Document Memorable Moments

Thursday, November 04, 2010

By Janice Crompton, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

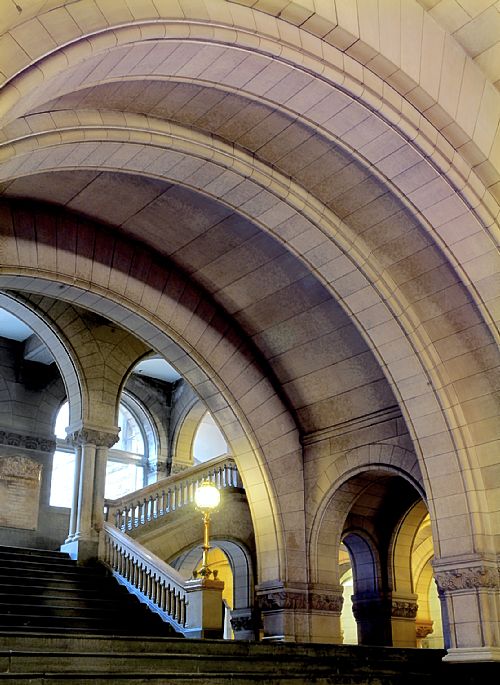

The dome inside the Washington County Courthouse, a building designed by Frederick J. Osterling. Bill Wade/Post-Gazette

The historic county courthouses of Western Pennsylvania are clearly more than mere buildings: Their walls bear witness to everything from birth to death.

They are, as Fayette County eloquently describes in a brochure, “… the scene of human drama, the repository of success and failure in life, the archive of the hopes and dreams of thousands.”

More than half of the courthouses of the 3,069 counties across the United States are recognized on the National Register of Historic Places, including five local ones: Allegheny, Butler, Fayette, Washington and Westmoreland.

This week, some of the courthouses, including those in Westmoreland and Beaver counties, took on a starring role as the official counting houses for Tuesday’s General Election.

Today, the majority of local county courthouses house the Common Pleas Court system and sometimes row offices, such as prothonotary, register of wills and clerk of courts. An exception is Allegheny County, which fused most row offices when voters approved a consolidation in 2005. The merger of the prothonotary, clerk of courts and register of wills offices formed the Department of Court Records, which is in the nearby City-County Building. But for the most part, the life-affirming and life-changing moments for each of us — births, marriages, home purchases and deaths — are recorded in a courthouse. And in the courthouse courtrooms, the drama of justice unfolds daily.

In addition, these buildings often honor and exhibit local history, such as the statue of the late Mayor Richard Caliguiri in Allegheny and the war memorials at the Washington and Beaver courthouses.

None of our local courthouses is an original. The first courthouses usually were primitive log cabins that gave way — often more than once — to grandiose architectural gems that have been rebuilt and reincarnated over the past two-plus centuries.

In his 2001 book, “County Courthouses of Pennsylvania,” Oliver P. Williams, a retired University of Pennsylvania political science professor, highlights each of Pennsylvania’s 67 courthouses. He visited each several times while doing his research.

In addition to providing details of architectural design, Dr. Williams examines the political climate and competitive atmosphere that led to the construction of some of the country’s finest monuments.

“I was always surprised how lavish public buildings were in the 19th century and how parsimonious they are now,” the 85-year-old said last week in a phone call from his home in Philadelphia. “There were plenty of tightwads in the 19th century, but the majority went the other way. Cities were in competition for growth and money.”

Before the interstate highway system was built, Dr. Williams traveled from Chicago to New York as a graduate student and he remembers seeing the tall spires of courthouses, beckoning travelers to visit their towns.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, courthouses typically were in the town square and the focus of local activity, he said. Trials there provided relief of boredom for spectators.

“Courtrooms were built like theaters,” Dr. Williams said. “They were big entertainment then.”

Several years ago, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court commissioned paintings of the state’s 67 county courthouses. Prints from those paintings are on display at the Pennsylvania Judicial Center, which opened in the summer of 2009 in Harrisburg.

Here’s a look at a half-dozen in our region:

Allegheny CountyThe Allegheny County Courthouse is “one of the most significant county courthouses in the United States from an architectural perspective,” Dr. Williams said.

Calling it “poetry in stone,” Dr. Williams wrote in his book that its beauty is an ideal example of Richardsonian Romanesque, an architectural style named for Henry Hobson Richardson, who believed, as his peers did, that the Allegheny County Courthouse was one of his crowning achievements.

“Richardson’s style was influential,” Dr. Williams said. “That courthouse was copied all over the nation.”

Mr. Richardson, also known for designing the Trinity Church in Boston, wanted to survive long enough to see the Allegheny County Courthouse completed, saying it was one of the works he wished to be judged by. He died, however, two years before it was finished in 1888.

The "bridge" looms over Ross Street and connects to Court of Common Pleas building, formerly to old Allegheny County Prison, to the Allegheny County Courthouse in Downtown Pittsburgh. It is still used to transport suspects to the "Bull Pen" to wait for their trials and hearings. Darrell Sapp/Post-Gazette

Primarily built from “Milford pinkish gray granite,” according to Dr. Williams’ book, the structure was designed with as many windows as possible, to provide natural lighting. The building’s 318-foot tower not only was symbolic but also served as a ventilation system, pulling in fresh air from above rather than the polluted air near street level.

The building also features four Norman towers with conical roofs along with moldings and ornamental stonework that were hand carved by 13 Americans and 13 Italians, according to literature provided by the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, which provides guided tours of the site.

“The thing that’s so extraordinary is the plan of the building,” said Albert Tannler, historical collections director for the foundation and author of a courthouse tour book. “It really is an amazing building.”

Possibly more impressive than the courthouse itself is the stone walkway, known as the “Bridge of Sighs,” that connects the courthouse to the jail, built at the same time and also designed by Mr. Richardson.

Patterned after the iconic bridge of the same name in Venice, the local bridge for decades provided a practical way to transport prisoners to and from the courthouse with minimal public contact.

Closed in 1995, the jail now serves as a family court center.

Beaver CountyLocated in Agnew Park in Beaver, the Beaver County Courthouse represents what Mr. Williams called “an architectural puzzle of a building.”

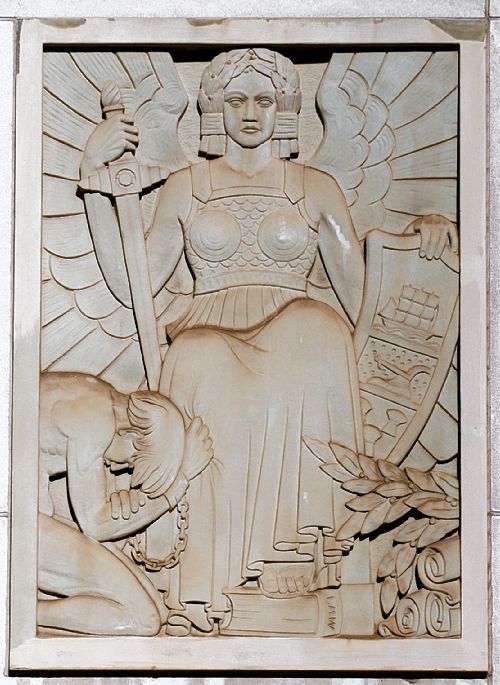

Concrete reliefs from the original Beaver County Courthouse now adorn the walls of the courtyard in the new courthouse, dedicated in January, 2003. Pam Panchak/Post-Gazette

Although it appears to be art moderne style, it contains unusual elements, such as a clock tower and a lunette, or crescent, window.

The eclectic mix is a result of a 1932 fire, which severely damaged the structure. Architects were able to salvage part of the burned 1875 courthouse, and they covered the new and old construction with a stone veneer, parts of which have been replaced over the years.

Butler CountyBuilt in 1885, the Butler County Courthouse has undergone several major alterations. Perhaps the most noticeable is the pointed stainless steel cap placed on its tower.

In his book, Mr. Williams explains how the shiny tower cap, which he calls “as durable as it is deforming,” was installed in 1958 after county commissioners found themselves unable to reject an offer of a free tower cap from Armco Steel.

The courthouse in Butler features a central clock tower with an elaborate cornice, a row of rosettes and arcaded corbels, or brackets, flanked by corner turrets, Mr. Williams said.

Gothic-arched windows on the first and second stories still have their stained-glass transoms.

Fayette CountyThe Fayette County courthouse is similar to the Richardsonian Romanesque style of the Allegheny County Courthouse, except it is smaller.

The gray sandstone courthouse in Uniontown features a 188-foot-tall central square tower, arcade windows and arched entryways. It also includes a “Bridge of Sighs” identical to the one in Allegheny County.

“Back in the day, that was the biggest compliment you could give an architect,” said Tammy Boyle, county human resources administrative assistant. “Today, you’d probably be sued.”

The design may have been borrowed from its neighbor to the north, but the structure is all Fayette County.

The stone was quarried locally, oak planks and panels were grown locally, and the iron for the building was rolled at a local mill. Even the brick used in the interior and for partition walls was made in the county.

The building has marble floors and iron stair railings, and the second-floor lobby contains four oval medallions, each 10 feet across, representing the county’s four leading industries at the time: coal mining, coke burning, agriculture and manufacturing.

While Ms. Boyle said the building is an architectural gem, it’s not without its drawbacks, especially when it comes to modern conveniences.

It’s no easy task to retrofit a historic building with wiring and security systems, not to mention plumbing and heating systems.

“There’s those days that we like it, and there’s those days when we don’t,” she said, speaking for county employees. “Sometimes in the winter it seems like we’re in Hades.”

Washington CountyWhen Debbie O’Dell Seneca was 13, she told her mother that she wanted to be a judge. She hadn’t yet laid eyes on the imposing sandstone and granite beaux-arts structure that is the Washington County Courthouse, but she never forgot the day she did.

“I was in complete awe,” she recalled. “It was like walking into a Roman cathedral.”

Today, she is Washington County president judge and she and others consider it an honor to work in the building, perched atop a large hill in Washington. It was built in 1900 and is crowned by a terra-cotta dome and statue of George Washington, both of which were recently refurbished.

Two 25-foot-high Italian Renaissance angels flanking the statue were removed when they began to deteriorate, but history buffs, including Judge O’Dell Seneca and county Commissioner J. Bracken Burns, have been pushing to have the angels restored.

Massive pilasters, Roman arches, Italian marble, bronze and highly polished brass grace the interior of the courthouse, which has a grand central stairway topped by a skylight.

Judge O’Dell Seneca said Architectural Digest in 1976 called it “one of the finest pieces of architecture in the United States.”

Westmoreland CountyAnother imposing and well-known beaux-arts style courthouse is in Greensburg.

Topped by a massive yellow-gold dome made of cast aluminum bronze over a rolled iron frame, the exterior is gray granite and “copiously decorated with the ornamental patterns learned at the Ecole des Beaux Arts,” Dr. Williams said.

The celebrated “Golden Dome,” as locals call it, is 175 feet above the sidewalk and arguably the signature piece on the county skyline.

Three arches grace the building’s entrance, framed by Corinthian pilasters, rosettes and bronze lamps. A marble staircase opens upward to twin spirals on the next floor. The structure contains marble walls in public halls, wall and ceiling murals, and a central rotunda that rises four stories to the domed ceiling.

The top of the building is graced by three female figures representing Justice, Guardian of the Law and Keeper of the Law — a fitting symbol for the courthouses themselves.

-

$22 Million Sustainable Reuse Project Transforms Former Mt. Washington School

Wednesday, November 03, 2010

Pop City Media

Abandoned for over 25 years and once the location of Mt. Washington’s highest crime rates, the former South Hills High School building at 101 Ruth Street is being reused and transformed into a 160,000 square-foot sustainable and affordable mixed-use community asset as the South Hills Retirement Residence.

“The building fell into terrible disrepair,” says Laura Nettleton, an architect at Thoughtful Balance Inc., who co-designed the building with Rothschild Doyno Collaborative. “There was a lot of water damage and the neighbors were dismayed when their property values fell.”

Working with developers Rodriguez Associates and Sota Construction, the architects installed 106 1- and 2-bedroom apartments for seniors, 22 of which are market rate and 84 that are age and income restricted. The ground floor contains a 7,500 square-foot space that will become a YMCA community fitness center and a 4,500 square-foot space that will become a daycare center.

The architects and developer expect to receive LEED Gold certification for the project, which contains sustainable features like a full-building spray foam insulation and an energy efficient mechanical system. The project team was awarded a grant for alternative energy systems, and there is a 27 kilowatt photovoltaic array on the roof and a gas fueled co-generation plant in the penthouse that generates power on site.

Funding for the $22 million project came from multiple sources, including the Pennsylvania Housing and Finance Agency, the URA, and Allegheny County.

Writer: John Farley

Source: Lura Nettleton, Thoughtful BalanceImage courtesy Thoughtful Balance

-

Carnegie Library Approves Plans to Renovate Historic South Side Branch

Wednesday, November 03, 2010

Pop City Media

The Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh Board of Trustees has unanimously agreed to make plans to renovate the South Side branch a top priority with funding to come from the Libraries for Life capital campaign that has set aside $2.7 million for renovating the aging building.

“The South Side does not have air conditioning and it’s a little over 100 years old. It’s not compliant with the guidelines of the Americans with Disabilities Act,” explains Suzanne Thinnes, communications manager for the Carnegie Library. “We find that when libraries are renovated they bring a new excitement to the community. More people discover the library and we see our circulation and account numbers go up.”

While the renovation process is in its early stages and an exact date for the project’s completion is currently ambiguous, a community meeting is scheduled at the South Side branch on November 17 at 6 p.m. to hear from the community about what they’d like to see preserved and changed about the library. Karen Loysen of Loysen + Kreuthmeier is the architect for the project and the upcoming meeting marks the start of a public dialogue that will create a vision for the library hoping to satisfy as many people as possible.

Writer: John Farley

Source: Suzanne Thinnes, Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh