Architecture Feature: Usonian Architecture in Metropolitan Pittsburgh

The idea for the Taliesin Fellowship had come to Mr. and Mrs. Wright at the depth of the Depression in 1932 when . . . architectural commissions had dribbled to zero. If there where no buildings to build, they thought, why not build “builders of buildings”? Mr. Wright was then 65 years old, an age when most people retire. But he was as youthful and fit as a man half his age and full of creative energy.— Cornelia Brierly, Tales of Taliesin, 1999

The Taliesin Fellowship

In 1932 Wright and his third wife Oglivanna created an apprentice program for young architects and would-be architects (it was not mentioned in the first edition of An Autobiography (1932) although it figures prominently in later editions). The Wrights’ plan combined innovative educational theory, Depression-era economic reality, and elements of 19th-century architectural apprenticeship. Those who sought architectural training in the 1880s had not been obliged to attend schools of architecture (although several fine ones existed) but could choose to work as apprentices under the direction of the senior staff in the office of an established architect. Wright had done this himself, working for J. Lyman Silsbee, W. W. Clay, and Adler & Sullivan, and he had established an apprentice system in his Oak Park studio in the 1890s.

The apprenticeship program he established in 1932 was called the Taliesin Fellowship, after Wright’s Wisconsin home. Apprentices paid a fee to work on Wright designs under Wright’s direction in the nearby Hillside School building, a private educational facility Wright designed for his aunts in 1901. In addition, the apprentices maintained the Taliesin buildings, worked on the Taliesin farm, shared food preparation duties, displayed their musical and theatrical talents, and participated in a communal existence revolving around the life and work of a master architect. The Taliesin Fellowship would be an integral part of Wright’s remaining 27 years which saw the design of some of the most acclaimed buildings of his career. Since his death in 1959, the Taliesin Fellowship has been one of the principal heirs of Wright’s estate.

Wrightian Design Centered in Southwestern Pennsylvania

Fallingwater, Frank Lloyd Wright’s great retreat for the Kaufmann family, was designed in 1935 and completed in 1938. During the 1930s Wright also explored more modest designs for moderately-priced homes suitable for 20th-century American lifestyles—a preoccupation of his throughout his career(s). He now called such houses “Usonian” (adapted from United States of America) and the house he designed in 1937 for the Jacobs family near Madison, Wisconsin is widely considered the first. Although the appearance of Usonian houses was not uniform, each house contained standardized elements to reduce construction costs while providing the kind of domestic environment Wright considered desirable—flat roofs, a carport instead of a garage, no basement, a heating system embedded in the floors, built-in indirect lighting, built-in furniture, natural wood cladding (rather than plaster or paint). Like all Wright houses, however modest, a fireplace was essential. Brick, stone, and wood were considered desirable building materials.

Cornelia Brierly and Peter Berndtson

One reader of An Autobiography was Cornelia Brierly, a Pittsburgh-area resident and Carnegie Institute of Technology architecture student. Inspired by the book and dissatisfied with her course of study, Cornelia applied for admission to the Taliesin Fellowship; she arrived in 1934 and was there while Fallingwater and the major projects of the 1930s were designed and constructed.[1] In 1938, Peter Berndtson, a Massachusetts native who had studied architecture at M.I.T., joined the Fellowship. Peter had worked as a painter and set designer in New York City, later apprenticing with an architectural firm there. Peter and Cornelia were married in 1939.

One reader of An Autobiography was Cornelia Brierly, a Pittsburgh-area resident and Carnegie Institute of Technology architecture student. Inspired by the book and dissatisfied with her course of study, Cornelia applied for admission to the Taliesin Fellowship; she arrived in 1934 and was there while Fallingwater and the major projects of the 1930s were designed and constructed.[1] In 1938, Peter Berndtson, a Massachusetts native who had studied architecture at M.I.T., joined the Fellowship. Peter had worked as a painter and set designer in New York City, later apprenticing with an architectural firm there. Peter and Cornelia were married in 1939.

In 1939 Cornelia designed Southwestern Pennsylvania’s first Usonian house for her aunts, Hulda and Louise Notz, in West Mifflin outside of Pittsburgh.[2] Soon after, the Berndtson’s moved to Spokane, Washington, returning when possible to Taliesin. In 1946, Cornelia and Peter and their two daughters moved to Laughlintown, PA, near Ligonier in Westmoreland County and established their architectural practice.

They designed buildings together for over a decade and divorced in 1957. That year. Cornelia decided to return to Taliesin as an interior designer and landscape architect with Taliesin Architects and instructor at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture.[3] Peter moved into Pittsburgh and established an office in East Liberty where he practiced until his death in 1972.[4]

The work of Cornelia Brierly (1913-2012) and Peter Berndtson (1909-1972) is not as well known as it should be. Both were trained by Frank Lloyd Wright, and together and separately they created some of the finest Wrightian residential architecture to be found anywhere.[5] Beginning with the Notz House of 1939 and taking into account their e leven-year joint practice and Peter’s work between 1958 and 1972, almost 90 designs have been documented. Most are residential, and while buildings were erected as far East as Franconia, New Hampshire, with one outside of Harrisburg and three near State College, most of the constructed buildings are in Westmoreland and Allegheny Counties.

leven-year joint practice and Peter’s work between 1958 and 1972, almost 90 designs have been documented. Most are residential, and while buildings were erected as far East as Franconia, New Hampshire, with one outside of Harrisburg and three near State College, most of the constructed buildings are in Westmoreland and Allegheny Counties.

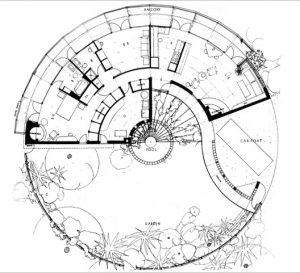

Many of the more ambitious projects were never realized: 3 of the 8 houses planned at Meadow Circles in West Mifflin (1947-50) were erected; St. Michael’s in the Valley Episcopal Church, Rector, PA (1951), although a modification of Peter’s design for the Parish House was erected in 1970; and an apartment building, multi-unit, and single-family dwellings on a 72-acre section of Mt. Washington (1957).

Cornelia Brierly and Peter Berndtson were able to realize approximately 40 constructed buildings of extraordinary quality, inspired and nurtured by Frank Lloyd Wright; they are masterworks of the next generation, progeny of the architectural community the older and wiser Wright did not deny.

Albert M. Tannler

PHLF E-News, December 2017

[1] Many of Cornelia’s writings during the 1930s are included in Randolph C. Henning, ed., At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship 1934-1937 (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1992): 58, 82, 85-87, 92, 94-95, 103, 110-12, 125-127, 129, 130, 139, 144, 151-55, 159-60, 170, 310.

[2] See Cornelia Brierly, “Notz House: A Shelter of Warmth and Rest,” Pittsburgh Tribune Review Focus 24:32 (June 13, 1999): 9.

[3] Cornelia Brierly, Tales of Taliesin: A Memoir of Fellowship (Arizona State University 1999).

[4] For Peter Berndtson’s work see Aaron Sheon. The Architecture of Peter Berndtson [An Exhibition of Contemporary Architectural Drawings, Photographs and Color Slides, The University Art Gallery, March 28th through April 18th, 1971] (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 1971) and Donald Miller and Aaron Sheon, Organic Vision: The Architecture of Peter Berndtson (Pittsburgh: The Hexagon Press, 1980).

[5] See James D. Van Trump, “Peter Berndtson, Pittsburgh Architect,” Carnegie Magazine 55:9 (November 1981, 27-29); Charles Rosenblum, “Precedent and Principle: The Pennsylvania Architecture of Peter Berndtson and Cornelia Brierly,” Frank Lloyd Wright Quarterly (Spring 1999): 12-15. Two houses designed jointly and one house designed by Peter Berndtson are in Tobias S. Guggenheimer, A Taliesin Legacy: The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Apprentices (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995): 27, 30, 37, 71, 98-101.