Architecture Feature: The African Heritage Room at the University of Pittsburgh

The design of the African Heritage Room was formally presented and approved on May 8, 1986. From left to right: Maxine Bruhns (former Director of the Nationality Rooms Program), William J. Bates (Architect), Dr. Larry Glasco (Concept Chairman), and Wesley W. Posvar (former President of the University of Pittsburgh).

By Larry Glasco

Both individually and collectively, the Nationality Rooms at the University of Pittsburgh constitute some of the most dramatic and beautiful examples of interior architecture in the city. Indeed, one might say in the world, for there is nothing like them anyplace else.

The Nationality Rooms program began in the late 1920s as part of an effort to enlist Pittsburgh’s nationality groups in support of the newly constructed Cathedral of Learning. The University stipulated that the rooms must be authentic representations of a national culture, must be cultural rather than political in design, and must represent a time before 1787, the year of the University’s founding.

Today, some 31 rooms grace the first and third floors of the Cathedral of Learning. They attract some 100,000 visitors annually, and serve as classrooms, regularly exposing students to a variety of world cultures.

In addition to their beauty, what most attracted me to the rooms is that they are designed by the nationality groups, not by the University. This makes them an expression of how the groups think of themselves and want to be perceived by others. The trade-off is that each group has to pay for its room, with the University agreeing to provide subsequent upkeep.

In addition to their beauty, what most attracted me to the rooms is that they are designed by the nationality groups, not by the University. This makes them an expression of how the groups think of themselves and want to be perceived by others. The trade-off is that each group has to pay for its room, with the University agreeing to provide subsequent upkeep.

As professor of African-American history at the University of Pittsburgh, I was excited to serve as chair of the Design Committee for the African Heritage Room. The most immediate problem we faced was that Africa is a continent, not a nationality. How to create a room that reflects that fact? The answer: designate the room as the African Heritage Room, meant to reflect the identity and cultural heritage—or at least the African cultural heritage—of black Americans.

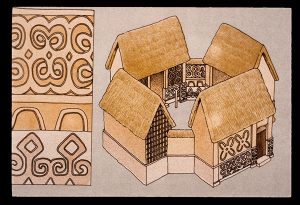

That identity is Pan-African, not based on any one African tribe or nationality, which allowed us to create a room that is both a blend of many cultural elements and an example of a specific African culture. We chose a courtyard as the room’s unifying concept, a place of gathering for friends and family. The courtyard is a feature of home life throughout the continent–the counterpart of the American front porch, backyard, and family room all rolled into one.

The African Heritage room is also a specific example of African architecture – that of the Asante, or Ashanti, people of Ghana. Finally, the room features (in subtle bas relief) examples of African written languages, musical instruments, art, science and mathematics.

One of my greatest pleasures was documenting the authenticity of everything in the room. To examine African artifacts, I visited the British Museum in London, the Museum of Mankind in Paris, and the Museum of Ethnology in Munich. I also traveled to Ghana, where I observed and photographed traditional temples and shrines in the countryside.

The room benefited from contributions by many individuals. African students at Pitt advised us about the importance of the courtyard. Lamidi Fakeye, a renowned traditional woodcarver from Nigeria, created the door, chalkboard, and lectern. Kweku Andrews, a Ghanaian professor of art, made the roof, stools and plasterwork.

The room benefited from contributions by many individuals. African students at Pitt advised us about the importance of the courtyard. Lamidi Fakeye, a renowned traditional woodcarver from Nigeria, created the door, chalkboard, and lectern. Kweku Andrews, a Ghanaian professor of art, made the roof, stools and plasterwork.

Pittsburgh-based architect William Bates (also a member of PHLF) turned ideas, photographs and documentation into a beautiful reality. Maxine Bruhns, the long-time director of the Nationality Rooms program, supported us every step of the way. Committee members, drawn from Pittsburgh’s black community, kept the faith and, under the leadership of Nancy Lee, raised over $150,000.

Today, the room’s current chair, Donna Alexander, leads the African Heritage Classroom Committee in advancing appreciation for Africa and African culture. Since the opening in 1989, it has been a joy to hear tour guides relate how the African Room remains one of the most popular and admired of all the many beautiful rooms.

The African Room’s current focus is providing scholarships for students to study and/or work in Africa. In addition, at Christmas time, the African room – like all the other rooms –is decorated, in our case with a Kwanzaa motif. In these, and in many other ways, the Nationality Rooms Program brings people together in a collective, mutually supportive way to celebrate their nationality alongside that of others. It promotes the sort of interracial and inter-ethnic atmosphere that is worthy of being cherished and cultivated.

Editor’s Note: We were saddened to learn of the recent death of Maxine Bruhns, the former longtime director of the Nationality Rooms Program at the University of Pittsburgh. She was a great friend of our organization, and we worked together for many years on a number of advocacy issues, including our support for the Nationality Rooms, which our organization awarded a historic landmark plaque. Read her obituary featured in the Post-Gazette here.

Larry Glasco is Associate Professor of History at the University of Pittsburgh. Since coming to the University of Pittsburgh’s History Department in 1969, he has focused on African-American history, both locally and globally. He is a longtime member and Board Member of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. He is a co-author of August Wilson: Pittsburgh Places in His Life and Plays, which was published by PHLF.