Abel Colley Tavern Helps Preserve Fayette County History

UNIONTOWN — Five miles west of this Fayette County seat stands the Abel Colley Tavern, a red-brick beacon of hospitality to travelers along the National Road during the 1800s.

Just one mile from Searight’s Toll House, the tavern was known for its moderate prices and hearty clientele of wagoners, who swapped many a tale over Monongahela Rye in its barroom.

By this time next year, it will be a place for even more stories as it becomes the Fayette County Museum. With 6,500 square feet, the restored building will have office space on the second floor for the Fayette County Historical Society, which currently has no regular space to meet; its members often house artifacts in their homes.

The last people to live there, Sue and Frank Dulik, left the property to Virginia and Warren Dick, who donated it to the society.

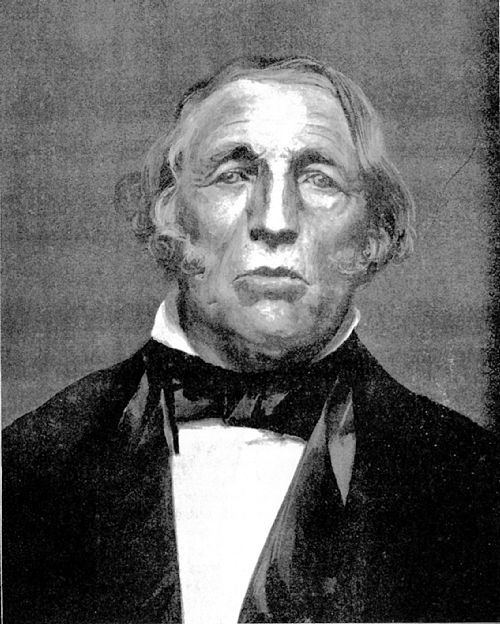

Jeremy S. Burnworth, president of the Fayette County Historical Society, stands inside the front door of the former Abel Colley Tavern, which has been restored and will become the society's new home next year. Marylynne Pitz

Jeremy S. Burnworth, the society’s 31-year-old president, is a Markleysburg native who has developed a passion for Fayette County’s rich history. At a convention in September of the American Association of State and Local History, Mr. Burnworth got excited when he learned about standardized software made by the Rescarta Foundation in Wisconsin that allows historical societies to photograph, log and archive materials.

“What a perfect opportunity to do it right from day one,” he said.

An advisory committee will oversee the museum’s operation and at least 30 people have volunteered to help staff the museum and toll house. One of Fayette County’s best-known residents has also pitched in. At an opening ceremony in July, the temperature rose to 99 degrees in the 19th-century building. Joe Hardy, the 84 Lumber tycoon and former Fayette County commissioner, offered afterward to pay for a new heating and cooling system.

One person who knows the building well is Tom Buckelew, a retired physiology professor from California University of Pennsylvania. He figures he has spent 1,500 hours working on restoring the former tavern.

“It had been modernized with drop ceilings and acoustic tile ceilings,” Mr. Buckelew said, adding that many of the rooms had four or five layers of wallpaper that had to be stripped before repainting with period-appropriate colors.

Just inside the front door is a large foyer with a staircase. On the ceiling is some of Mr. Buckelew’s best craftsmanship — a hand-carved ceiling medallion that lends elegance to the new chandelier.

“I roughed out the medallion with a band saw and then just carved the rest. That was about two weeks, three hours a day,” he said.

On the second floor is a large ballroom where Mr. Buckelew painted an intricate, ruglike pattern of mustard, brick red and chocolate brown. It’s actually a centuries-old trick for disguising uneven floors.

“It was a way of capitalizing on bad design,” he said, adding that the front part of the ballroom is probably an inch lower than the back portion. “That was a feature that a lot of people adopted in the early 19th century. In lieu of rugs, you paint a rug on the floor.”

A team of inmates from SCI-Greene spent two weeks hanging dry wall in the building. A new ceiling was attached to a plaster-and-lathe one in the second-floor ballroom. Then, Mr. Buckelew put up crown molding with the help of another volunteer, Bill Zin. Joe Petrucci, a township supervisor in Menallen, donated 400 board feet of molding.

“That ceiling is tied to irregular joists. So the ceiling naturally has some dips in it, high spots and low spots,” Mr. Buckelew said, adding that the crown molding camouflages the dips.

The building, done in a vernacular Greek Revival style, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1995. Jerry Clouse, who nominated the building for federal designation, dates the structure to around 1835. He said two architectural features signify its use as a tavern: the kitchen ell with a double-stacked porch and two front doors, one of which opens into the barroom.

At least one historian believes it may have been a home much longer than it was a tavern. Ronald L. Michael, a retired anthropologist who excavated around the nearby Peter Colley Tavern in 1973, believes Abel Colley’s famous tavern stood on the opposite side of Route 40, partly because there was once a well on that property which would have provided water for travelers and horses.

Abel Colley owned a Fayette County tavern just outside of Uniontown on U.S. Route 40. Volunteers have restored the 19th-century building during the past year. The former tavern will become the Fayette County Museum next year and also will provide office space for the Fayette County Historical Society.

The building that locals know as the Abel Colley Tavern, Dr. Michael said, is more likely the house he built after making his fortune in the hospitality business, then retiring. Mr. Burnworth agrees but still treasures its history.

“It was probably only a tavern, if ever, for a very short period of time,” he said. “He died a few years after we believe it was built. Most likely, it was his home.”