Courthouses Tower as Testaments to Our Pursuit of Justice, Desire to Document Memorable Moments

Thursday, November 04, 2010

By Janice Crompton, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

The dome inside the Washington County Courthouse, a building designed by Frederick J. Osterling. Bill Wade/Post-Gazette

The historic county courthouses of Western Pennsylvania are clearly more than mere buildings: Their walls bear witness to everything from birth to death.

They are, as Fayette County eloquently describes in a brochure, “… the scene of human drama, the repository of success and failure in life, the archive of the hopes and dreams of thousands.”

More than half of the courthouses of the 3,069 counties across the United States are recognized on the National Register of Historic Places, including five local ones: Allegheny, Butler, Fayette, Washington and Westmoreland.

This week, some of the courthouses, including those in Westmoreland and Beaver counties, took on a starring role as the official counting houses for Tuesday’s General Election.

Today, the majority of local county courthouses house the Common Pleas Court system and sometimes row offices, such as prothonotary, register of wills and clerk of courts. An exception is Allegheny County, which fused most row offices when voters approved a consolidation in 2005. The merger of the prothonotary, clerk of courts and register of wills offices formed the Department of Court Records, which is in the nearby City-County Building. But for the most part, the life-affirming and life-changing moments for each of us — births, marriages, home purchases and deaths — are recorded in a courthouse. And in the courthouse courtrooms, the drama of justice unfolds daily.

In addition, these buildings often honor and exhibit local history, such as the statue of the late Mayor Richard Caliguiri in Allegheny and the war memorials at the Washington and Beaver courthouses.

None of our local courthouses is an original. The first courthouses usually were primitive log cabins that gave way — often more than once — to grandiose architectural gems that have been rebuilt and reincarnated over the past two-plus centuries.

In his 2001 book, “County Courthouses of Pennsylvania,” Oliver P. Williams, a retired University of Pennsylvania political science professor, highlights each of Pennsylvania’s 67 courthouses. He visited each several times while doing his research.

In addition to providing details of architectural design, Dr. Williams examines the political climate and competitive atmosphere that led to the construction of some of the country’s finest monuments.

“I was always surprised how lavish public buildings were in the 19th century and how parsimonious they are now,” the 85-year-old said last week in a phone call from his home in Philadelphia. “There were plenty of tightwads in the 19th century, but the majority went the other way. Cities were in competition for growth and money.”

Before the interstate highway system was built, Dr. Williams traveled from Chicago to New York as a graduate student and he remembers seeing the tall spires of courthouses, beckoning travelers to visit their towns.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, courthouses typically were in the town square and the focus of local activity, he said. Trials there provided relief of boredom for spectators.

“Courtrooms were built like theaters,” Dr. Williams said. “They were big entertainment then.”

Several years ago, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court commissioned paintings of the state’s 67 county courthouses. Prints from those paintings are on display at the Pennsylvania Judicial Center, which opened in the summer of 2009 in Harrisburg.

Here’s a look at a half-dozen in our region:

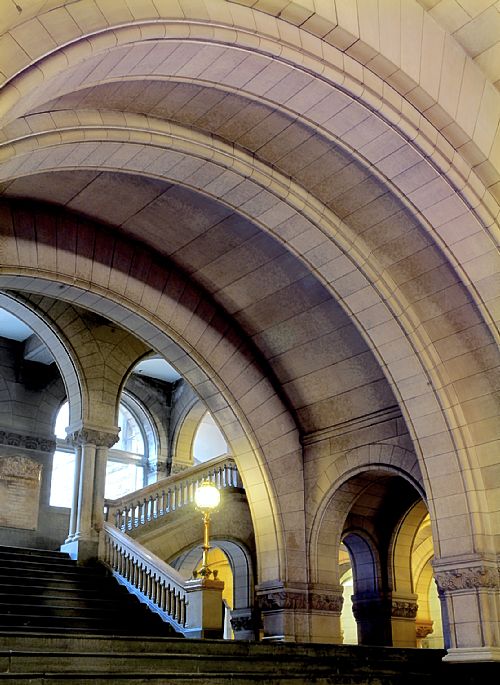

The Allegheny County Courthouse is “one of the most significant county courthouses in the United States from an architectural perspective,” Dr. Williams said.

Calling it “poetry in stone,” Dr. Williams wrote in his book that its beauty is an ideal example of Richardsonian Romanesque, an architectural style named for Henry Hobson Richardson, who believed, as his peers did, that the Allegheny County Courthouse was one of his crowning achievements.

“Richardson’s style was influential,” Dr. Williams said. “That courthouse was copied all over the nation.”

Mr. Richardson, also known for designing the Trinity Church in Boston, wanted to survive long enough to see the Allegheny County Courthouse completed, saying it was one of the works he wished to be judged by. He died, however, two years before it was finished in 1888.

The "bridge" looms over Ross Street and connects to Court of Common Pleas building, formerly to old Allegheny County Prison, to the Allegheny County Courthouse in Downtown Pittsburgh. It is still used to transport suspects to the "Bull Pen" to wait for their trials and hearings. Darrell Sapp/Post-Gazette

Primarily built from “Milford pinkish gray granite,” according to Dr. Williams’ book, the structure was designed with as many windows as possible, to provide natural lighting. The building’s 318-foot tower not only was symbolic but also served as a ventilation system, pulling in fresh air from above rather than the polluted air near street level.

The building also features four Norman towers with conical roofs along with moldings and ornamental stonework that were hand carved by 13 Americans and 13 Italians, according to literature provided by the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, which provides guided tours of the site.

“The thing that’s so extraordinary is the plan of the building,” said Albert Tannler, historical collections director for the foundation and author of a courthouse tour book. “It really is an amazing building.”

Possibly more impressive than the courthouse itself is the stone walkway, known as the “Bridge of Sighs,” that connects the courthouse to the jail, built at the same time and also designed by Mr. Richardson.

Patterned after the iconic bridge of the same name in Venice, the local bridge for decades provided a practical way to transport prisoners to and from the courthouse with minimal public contact.

Closed in 1995, the jail now serves as a family court center.

Located in Agnew Park in Beaver, the Beaver County Courthouse represents what Mr. Williams called “an architectural puzzle of a building.”

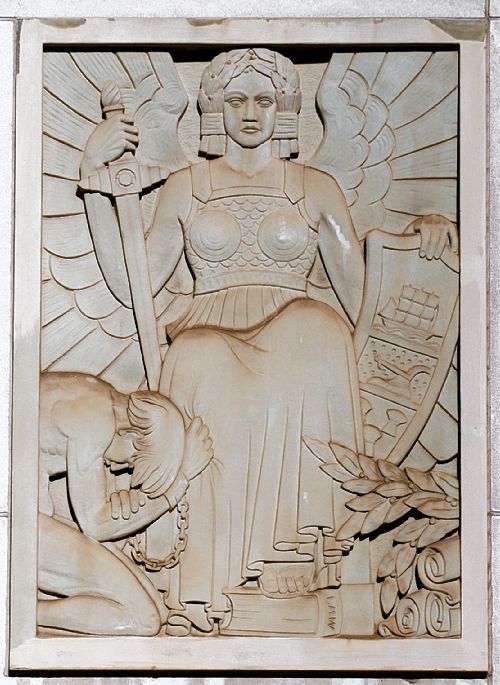

Concrete reliefs from the original Beaver County Courthouse now adorn the walls of the courtyard in the new courthouse, dedicated in January, 2003. Pam Panchak/Post-Gazette

Although it appears to be art moderne style, it contains unusual elements, such as a clock tower and a lunette, or crescent, window.

The eclectic mix is a result of a 1932 fire, which severely damaged the structure. Architects were able to salvage part of the burned 1875 courthouse, and they covered the new and old construction with a stone veneer, parts of which have been replaced over the years.

Built in 1885, the Butler County Courthouse has undergone several major alterations. Perhaps the most noticeable is the pointed stainless steel cap placed on its tower.

In his book, Mr. Williams explains how the shiny tower cap, which he calls “as durable as it is deforming,” was installed in 1958 after county commissioners found themselves unable to reject an offer of a free tower cap from Armco Steel.

The courthouse in Butler features a central clock tower with an elaborate cornice, a row of rosettes and arcaded corbels, or brackets, flanked by corner turrets, Mr. Williams said.

Gothic-arched windows on the first and second stories still have their stained-glass transoms.

The Fayette County courthouse is similar to the Richardsonian Romanesque style of the Allegheny County Courthouse, except it is smaller.

The gray sandstone courthouse in Uniontown features a 188-foot-tall central square tower, arcade windows and arched entryways. It also includes a “Bridge of Sighs” identical to the one in Allegheny County.

“Back in the day, that was the biggest compliment you could give an architect,” said Tammy Boyle, county human resources administrative assistant. “Today, you’d probably be sued.”

The design may have been borrowed from its neighbor to the north, but the structure is all Fayette County.

The stone was quarried locally, oak planks and panels were grown locally, and the iron for the building was rolled at a local mill. Even the brick used in the interior and for partition walls was made in the county.

The building has marble floors and iron stair railings, and the second-floor lobby contains four oval medallions, each 10 feet across, representing the county’s four leading industries at the time: coal mining, coke burning, agriculture and manufacturing.

While Ms. Boyle said the building is an architectural gem, it’s not without its drawbacks, especially when it comes to modern conveniences.

It’s no easy task to retrofit a historic building with wiring and security systems, not to mention plumbing and heating systems.

“There’s those days that we like it, and there’s those days when we don’t,” she said, speaking for county employees. “Sometimes in the winter it seems like we’re in Hades.”

When Debbie O’Dell Seneca was 13, she told her mother that she wanted to be a judge. She hadn’t yet laid eyes on the imposing sandstone and granite beaux-arts structure that is the Washington County Courthouse, but she never forgot the day she did.

“I was in complete awe,” she recalled. “It was like walking into a Roman cathedral.”

Today, she is Washington County president judge and she and others consider it an honor to work in the building, perched atop a large hill in Washington. It was built in 1900 and is crowned by a terra-cotta dome and statue of George Washington, both of which were recently refurbished.

Two 25-foot-high Italian Renaissance angels flanking the statue were removed when they began to deteriorate, but history buffs, including Judge O’Dell Seneca and county Commissioner J. Bracken Burns, have been pushing to have the angels restored.

Massive pilasters, Roman arches, Italian marble, bronze and highly polished brass grace the interior of the courthouse, which has a grand central stairway topped by a skylight.

Judge O’Dell Seneca said Architectural Digest in 1976 called it “one of the finest pieces of architecture in the United States.”

Another imposing and well-known beaux-arts style courthouse is in Greensburg.

Topped by a massive yellow-gold dome made of cast aluminum bronze over a rolled iron frame, the exterior is gray granite and “copiously decorated with the ornamental patterns learned at the Ecole des Beaux Arts,” Dr. Williams said.

The celebrated “Golden Dome,” as locals call it, is 175 feet above the sidewalk and arguably the signature piece on the county skyline.

Three arches grace the building’s entrance, framed by Corinthian pilasters, rosettes and bronze lamps. A marble staircase opens upward to twin spirals on the next floor. The structure contains marble walls in public halls, wall and ceiling murals, and a central rotunda that rises four stories to the domed ceiling.

The top of the building is graced by three female figures representing Justice, Guardian of the Law and Keeper of the Law — a fitting symbol for the courthouses themselves.