George W. Sotter (1879-1953), Pittsburgh

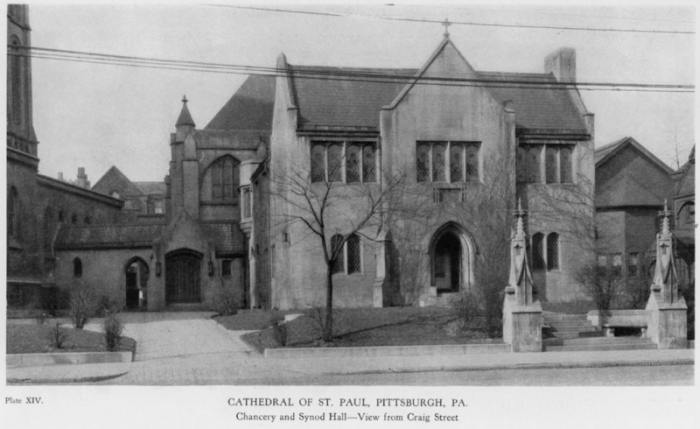

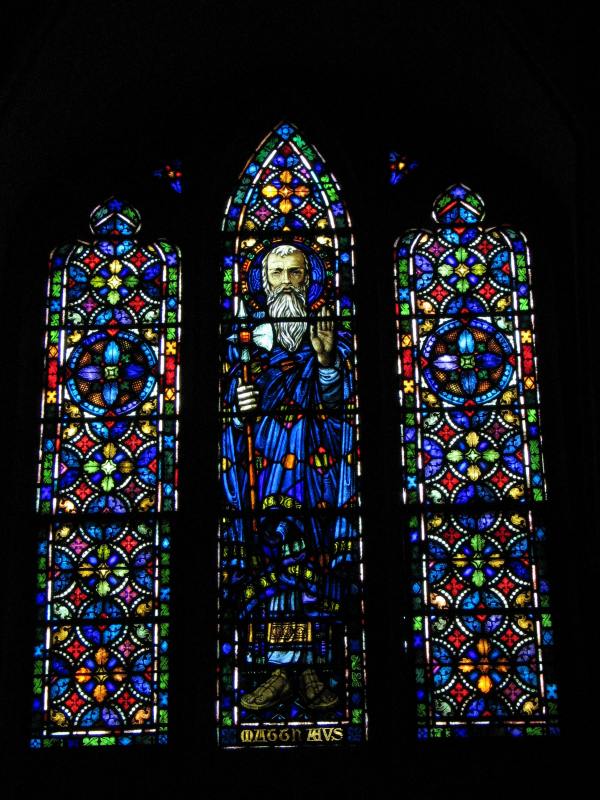

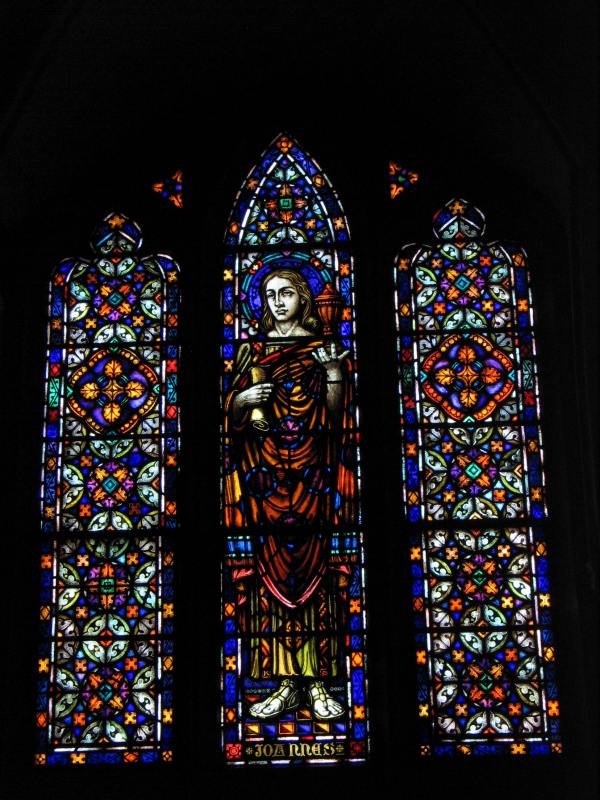

George W. Sotter (1879-1953), Pittsburgh: St. Matthew and St. John, 1914-15, Synod Hall; Edward J. Weber, architect

Photographs of St. Matthew and St. John and text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

The invention of opalescent glass and the “painterly” approach to glass windows that prized pictorial realism above all were largely byproducts of the prevailing “American Renaissance.” By 1910 the character of stained glass art in the United States had changed. Around 1900 Otto Heinigke of Brooklyn began combining native opalescent glass with traditional hand-blown antique glass, and revived leading as a technical and aesthetic component in window making. In 1902 Harry E. Goodhue, brother of architect Bertram G. Goodhue, revived medieval techniques and iconography in the first large all-antique glass window in the United States in Newport, Rhode Island; this was followed by a similar window designed and made 1904-05 by William Willet at the First Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh. Influenced by William Morris and the English Arts and Crafts movement, American glass artists came to appreciate the architectural character of windows as openings in the wall rather than as self-referential glass paintings. The purity of color and the architectural fitness of the medieval stained glass window was no longer viewed as primitive but was now seen as an appropriate and technologically sophisticated element in a new architectural language based on medieval forms, begun by H. H. Richardson and subsequently championed by architects Ralph Adams Cram, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, and other adherents of 20th-century American Gothic.

Heinigke, Harry Goodhue, and Willet had all been trained as painters before working with stained glass and they had tentatively made the journey from one medium to another. Their pioneering efforts made it possible for those in the following generation to more readily recognize that different techniques and approaches were required by the easel painter and the stained glass craftsman. Some artists found both worlds congenial.

George William Sotter was one such artist. Born into a Roman Catholic family in Pittsburgh, he apprenticed in several glass shops before studying painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia at the urging of Horace Rudy. In a memorial tribute to Rudy he recalled:

I had come under William Willet, and worked in four shops before meeting Rudy. I shall never forget how Rudy received me, looked at my paintings and gave me an opportunity to work with him. In glass as well as in painting he fed me with his enthusiasm to keep going and keep trying. He was always happy over any success that came to me. He gave and loaned me books, took me to plays . . . . He saw to it that I met all his friends,—Henri, Sloan and Redfield,—saw that I had a leave of absence to go to the Pennsylvania Academy. Then when I studied under Redfield, he extended my leave two more months.

Joan Gaul tells us that Sotter attended the Pennsylvania Academy 1901-02 and returned to Rudy Brothers in 1903. There he met Alice Bennet (1883-1967), who entered the Rudy shop as an apprentice in 1904; they married in 1907.

Sotter successfully—often simultaneously—painted, taught painting, and designed stained glass. He exhibited paintings at the Pennsylvania Academy, the Carnegie Institute, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, 1904, and the Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D. C. He was active in the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh (established 1910), participating in their annual exhibitions. He taught painting at Carnegie Institute of Technology 1910-1919 in Pittsburgh. He designed stained glass for Pittsburgh Stained Glass Company and Petgen Company, and he and his wife collaborated on stained glass projects.

Sotter’s first documented windows, installed in the Church of the Epiphany in Pittsburgh as part of a 1910 renovation supervised by architect John T. Comes, are simple, primarily geometric, and self-effacing. (Sotter has been credited with the original 1903 windows; these are not his work but were almost certainly made by Ludwig von Gerichten of Columbus, Ohio.) At least two churches from this period that had Sotter windows have been demolished, although his 1911 clerestory windows in Comes’ St. Gertrude, Vandergrift, survive.

Sotter’s first noteworthy stained glass windows are in the Synod Hall and Chancery building, adjacent to St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Cathedral, seat of the Pittsburgh Diocese. The windows, in place when the building opened April 12, 1915, include secondary windows in the library, offices, the auditorium stairway, and the impressive, almost life-sized twelve apostles who light the balcony in the auditorium. The Gazette Times described the twelve apostles:

The windows are so designed that the light from the outside filtering through their prismatic colors makes pure white light. The hall is not to be used every hour of the day, nor for reading, nor writing, nor for office purposes: hence very little natural light is required. The twilight of a clear day is perhaps the most favorable time for appreciating the amazing, deep, gem-like coloring of the windows. The tones are as rich and as soft as those of a Persian rug, and the black lead lines give a continual contrast to the glowing labyrinth of translucent jewels. The windows are 12 in number, each dedicated to an apostle, each twinkling with an almost barbaric burst of color.

Notable windows followed in the Diocese of Pittsburgh; in particular those at St. Agnes, 1917-18 (now the Carlow University chapel) and St. Paul of the Cross Monastery, 1919. In 1919, the Sotters moved to Holicong, Pa. in Bucks County. George Sotter painted (one of his paintings recently sold for $110,000) and the Sotters continued to create stained glass windows. A group of windows created for St. Canice Church in Pittsburgh c. 1930 has been reinstalled at St. Paul’s Cathedral, but the Sotters’ most notable achievement are the windows for Sacred Heart Roman Catholic Church in Pittsburgh, designed and made between 1930 and 1954 and completed by Alice Sotter after her husband’s death in 1953.

Synod Hall was designed by Edward J. Weber (1877-1968). Weber apprenticed with architectural firms in Boston and studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He arrived in Pittsburgh c. 1906 and designed a substantial number of handsome schools (public as well as parochial) and ecclesiastical buildings and wrote about church architecture. George Sotter designed the windows for Edward Weber’s St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Cathedral, Wheeling, West Virginia.

Sources: “The Pittsburg Stained Glass Co.,” Up-Town, Greater Pittsburg’s Classic Section; East End, The World’s Most Beautiful Suburb (Pittsburgh Board of Trade, 1907), n.p. “Art.” The Index, 22 June 1907: 25. Lawrence B. Saint, “The Art of a Pittsburgher,” The Bulletin, 14 May 1910: 11. “Building a Triumph,” Gazette Times, 12 April 1915. George Sotter, “J. Horace Rudy, Master of Friendship,” Stained Glass 35 (Spring 1940): 32-33. Jean M. Farnsworth, “Biographical Sketches of Stained: 45, 53, 55.

Illustrations

- Synod Hall. Photograph taken from Edward J. Weber, Catholic Ecclesiology (Pittsburgh 1927): Plate XIV.

- St. Matthew

- St. John