Treasure in the Cathedral—A. W. N. Pugin in Pittsburgh

By Albert M. Tannler

Historical Collections Director

English Room, Nationality Rooms at Cathedral of Learning, University of Pittsburgh, Oakland, interior, fragments from the House of Commons; Augustus W. N, Pugin, architect for fragments. Photograph by Keith Hoden for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review Focus Magazine

Some stories do get more interesting, and some places are discovered to be more important than first assumed. Take, for example, one of the Nationality classrooms at the University of Pittsburgh.

It was John G. Bowman, the university’s visionary chancellor of the 1920s, who proposed decorating classrooms in the Collegiate Gothic/Art Moderne Cathedral of Learning (designed by Charles Z. Klauder, 1926-37) in the manner of the countries of origin of Pittsburgh’s multi-ethnic residents. The program began in 1926, each room was to be decorated in a national style prior to 1787 (given as the date of the founding of the university), and the first rooms opened in 1938.

A unique opportunity arose after World War II when the London member of the committee to plan an English Nationality Room, Alfred C. Bossom, M.P. (Member of Parliament; later Lord Bossom) learned that architectural elements salvaged from the House of Commons, bombed on May 10, 1941, could be made available to the university.[1]

The destroyed House of Commons had been completed in the 1850s; thus the inclusion of 19th-century architectural fragments in this Nationality Room represented a variance from the official pre-1787 design policy. Thanks to this bending of the rules the English Room acquired unique, one might say, invaluable 19th-century elements.[2]

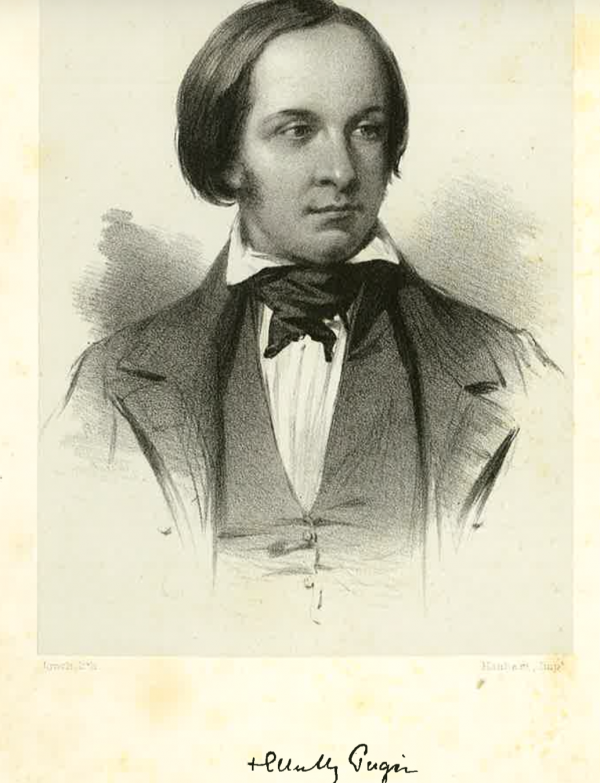

The designer was Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin—one of England’s most important and influential architects and designers.

The Designer

Augustus W. N. Pugin was born in London in 1812, the only child of French émigré Augustus C. Pugin and his English wife, Catharine neé Welby. The elder Pugin was a noted illustrator, architectural draftsman, and drafting teacher. He began his pioneering measured drawings of medieval buildings, “Specimens of Gothic Architecture,” in 1818. His son became his most accomplished pupil, so proficient that by the age of 13 he was preparing plates for his father’s books (and would complete the third and final volume of “Specimens” in 1833).

Augustus W. N. Pugin was born in London in 1812, the only child of French émigré Augustus C. Pugin and his English wife, Catharine neé Welby. The elder Pugin was a noted illustrator, architectural draftsman, and drafting teacher. He began his pioneering measured drawings of medieval buildings, “Specimens of Gothic Architecture,” in 1818. His son became his most accomplished pupil, so proficient that by the age of 13 he was preparing plates for his father’s books (and would complete the third and final volume of “Specimens” in 1833).

Pugin’s education was more activist and practical than formal and academic. He was tutored at home, studied buildings in Britain and France on family trips, and was an avid user of the Print Room at the British Museum. Convinced of the superiority of the “pointed style”—so called after the pointed shape of the late medieval Gothic arch—he began to design furniture and metalwork at an early age. At the age of 15, he was asked to design tables and chairs for Windsor Castle and goblets and candle sticks for the royal silversmiths. Later he worked as a stage carpenter and set designer. Designs for wallpaper, textiles, stained glass, and ceramic tiles based on medieval forms followed, and he collaborated with several architects as an interior designer. He became a collector—and seller—of medieval antiquities.

He published his first book, “Gothic Furniture of the 15th Century Designed and Etched by A. W. N. Pugin” (1835), at the age of 23. Later that year he became a Roman Catholic, and thereafter he wrote books and pamphlets to demonstrate that Gothic was the definitive English architectural style and that the Roman Catholic Church was the legitimate Church of England. The most influential of his many books are “Contrasts: or a Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, and Similar Buildings of the Present Day; Shewing the Present Decay of Taste” (1836), “The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture” (1841), “An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture” (1843), and “Foliated Ornament” (1849).

Pugin designed his first home in 1835 and while he designed a few houses, his principal works as an architect were over 40 churches, and numerous chapels, convents, abbeys, schools, hospitals, parish houses, church interiors, and ecclesiastical restorations in England, Ireland, and Australia.

He was married three times—his first two wives died young (the third outlived him by 57 years)—and he fathered eight children. Contemporaries characterized him as sociable, erudite, energetic, and supremely self-confident in his opinions. He loved the sea and owned and sailed boats. He presented a somewhat bohemian appearance, often mixing nautical garb with other garments he designed or modified, such as a greatcoat whose large inner pockets held all his travel needs, making luggage superfluous.

From 1836 to 1852, Pugin worked on the most important commission of his age: rebuilding the Palace of Westminster (Houses of Parliament), partially destroyed in a fire in 1834. The work was essentially finished with the opening of the House of Commons in February 1852. On September 14, 1852, Pugin died. He was 40 years old.

Pugin, the New Palace of Westminster, and the English Nationality Room

When architect Charles Barry received the commission to design a new Palace of Westminster—one preserving historical elements dating from the 11th century as well as providing the latest in Victorian efficiency and comfort, all within an architecturally harmonious and regal façade—he turned to Pugin for assistance. Pugin was responsible for all aspects of the interior design, and Barry also drew upon his ideas for various exterior details—the famous clock tower, for example, is similar to a Pugin design of 1835.

To unify (and simplify) the extensive program of decoration, Pugin used a number of recurring motifs, treated lavishly in the House of Lords and the Royal apartments, and more simply in the House of Commons. Among them are the Tudor rose, a five-petal marriage of the white rose of York and the red rose of Lancaster; Tudor flowers, cross-shaped patterns with foliage extremities; the Queen’s monogram, “VR” (Victoria Regina); and the portcullis, i.e., a medieval entrance grille raised and lowered vertically; all are used on furniture, upholstery, wallpapers, tiles, etc.

The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture defines “Tudor Architecture” as follows: “Architecture in England during the Tudor monarchy (of Henry VII (1488-1509), Henry VIII (1509-47), Edward VI (1547-53), Mary I (1553-8), and Elizabeth I (1558-1603). . . . ‘Tudor’ is primarily associated with late Perpendicular Gothic, very flat four-centered or Tudor arches, domestic architecture of brick with diaper-patterns, elaborate chimney of carved and molded brick, and square-headed mullioned windows. . . .”[3] ‘Perpendicular’ is defined as the “third and latest of English Gothic architectural styles. . . . An English style, it has no Continental, Irish, or Scottish equivalent, and survived for more than three centuries. . . . It was the first of the Gothic styles to be revived in [the]18[th] [century].”[4]

The possibility of elements from the House of Commons changed the character of the English Room as it had previously been conceived at the University. As Ruth Crawford Mitchell wrote to Alfred Bossom in early 1948: “May I say that I have far greater enthusiasm for this new concept of the English Room than for the Tudor Period Room about which we spoke in 1946.”[5]

With the approval of the Speaker of the House, the architectural elements from the House of Commons were sent to Pittsburgh; they arrived on March 13, 1950. Later that year the earlier proposal for the English nationality room was revised as The English Room in the Cathedral of Learning: Revised Memorandum on Design proposal on the basis of conference and correspondence with Alfred C. Bossom, M.P., Architect A. A. Klimcheck, University Architect, and John Weber, Secretary of the Board of Trustees (November 2, 1950).[6]

In late February 1951, Mrs. Mitchell wrote to Alfred Bossom, noting that the House of Commons elements had arrived and that: “Mr. Klimcheck has completed elevation drawings of a proposed design for the English Room incorporating the House of Commons materials in a Tudor Gothic Design.”[7] Three days later she wrote: “Mr. Klimcheck was guided in part by the revised Memorandum on Design dated November 2, 1950, but chiefly, of course, by his knowledge of Tudor Gothic. . . .”[8] Despite Mrs. Mitchell’s “far greater enthusiasm for this new concept of the English Room than for the Tudor Period Room” that enthusiasm was not shared by the university architect who apparently objected to the tile facing in the fireplace, which was denigrated as “Victorian pseudo-Gothic.” Thus Mrs. Mitchell wrote to Chancellor R. H. Fitzgerald in early July 1951: “Shall emphasis in design be pure Tudor Gothic (No use of tile facing in fireplace.) or Victorian pseudo-Gothic? (use of tile facing, coal basket, House of Commons brass hardware, etc.)”[9] It would seem that architect Klimcheck preferred his own Twentieth-century Pseudo-Tudor Gothic design to a genuine architectural element from the House of Commons. Indeed, Bossom would write to British Consulate General James Robinson in Philadelphia in May 1952: “The tiles are the ones arranged by the famous architect, Welby-Pugin, when he fitted up the interior decoration and designing after the fire of 1834.[10] They were probably installed about 1850 and they are entirely authentic and to be relied upon in every way.”[11] Furthermore, the fireplace (and its tiles) was an important survivor, as Bossom wrote to Mrs. Mitchell later that month: “you have the fireplace from the Aye Lobby which most happily I had the good fortune to be able to retrieve practically intact.”[12] Nonetheless the university architects (note the plural) had no interest in this important architectural element. On May 21, 1952, Mrs. Mitchell wrote again to Bossom: “Please tell us about the use of the tile surround. The architects here insist that such a facing does not belong in an authentic Tudor Room. I have held to the possibility that the Room is Victorian Tudor-Gothic and that the tile surround was conceived in order to use a coal basket and a fireback for the fireplace rather than firedogs. What is your advice?”[13] Bossom wrote back: “As to the tile in the fireplace, I am afraid anybody who questioned these did not quite understand that this fireplace was actually taken from the Aye Lobby, and the tiles, some of which were I understand designed by Welby Pugin, the architect who did all the interior designing in the House, are the ones originally installed.”[14]

The English Nationality Room was dedicated November 21, 1952. As one enters the English Nationality Room, one faces the north or Fifth Avenue side of the Cathedral. The Pugin wall, if I may so designate it, is the south end of the room. The distinctive oak paneling, interrupted by the stone fireplace, continues across the wall to meet the elaborate wooden doorframe on the west side of the room. The oak paneling is called “linenfold,” because of its resemblance to folded fabric; the ornamental cresting above the doorframe lintel is a garland of Tudor flowers topped by a rope molding that stretches between tall foliated finials (decorative knobs). (A plaque above the fireplace inscribed with a quotation from Shakespeare’s “Richard II”; a Royal Coat of Arms circa 1618 above the doorway; and the double doors were either installed by university architect Klimcheck when the room was created 1950-52 or added at a later date.) The paneling, the fireplace, and the doorframe were designed by Pugin.

The fireplace with the Minton tile surround installed. Photograph courtesy of English Nationality Room Collection, 1929-1981, UA.40.07, University Archives, Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh.

The fireplace was originally located in the Aye Lobby of the House of Commons. Hans Wild describes this room in “Westminster Palace” (1946): “On the left and right of the Chamber, doorways gave on to the narrow “Aye” and “No” or “Division” Lobbies, by entering which M.P.’s record their vote on any bill or motion.”

The face of the fireplace is carved limestone (bearing scars from the bombing.) The opening is a composite Tudor arch (concentric arches meeting at a shallow point). The upper section is decorated with three shields; between the shields ribbon-like banners nestle among oak leaves and acorns. Below on either side is Queen Victoria’s monogram, set within a tangle of ribbons. The original fireplace surround held a wide border of Minton tile; the Minton firm was established by Thomas Minton in 1793 and subsequently led by his son Herbert Minton (1793–1858). An early photograph shows exuberant foliate patterns within a Gothic framework. The tile surround was quintessential Pugin, who “brought together … the revival of medieval practice and the celebration of nature,” as Stuart Durant observed in “Ornament” (1986); such designs profoundly influenced William Morris and his successors.

The fireplace floor or hearth is composed of seven rows of ceramic russet tiles 9 inches by 1 1/2 inches, laid in a herringbone pattern, which extend out into the room. In the center of the outer hearth, four six-inch red, gold, and black tiles are set in a 12 inch by 12 inch diamond pattern—oak leaves at the edges and Tudor flowers in the middle radiate from the central Tudor rose. The tile, called encaustic or inlaid tile, was made by Minton.

Two roundels of stained glass fragments from windows in the House of Commons. Photographs by Keith Hoden for the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review Focus Magazine.

Within the room are additional elements designed by Pugin. Two of the six roundels (round panels) of stained glass in the windows facing Fifth Avenue contain shards from Pugin’s stained glass windows, shattered in 1941.[15] He designed the four limestone corbels or brackets ornamented with giant Tudor roses that appear to support the ceiling. Among the furnishings are two of the simple, sturdy oak side chairs upholstered in green leather that Pugin designed for use throughout the House of Commons. (His similar version for the House of Lords has more ornate legs.) The green leather backs are embossed with a gold portcullis topped by a coronet and framed by links of chain. Alfred Bossom noted that these chairs had been rebuilt from chairs damaged in the bombing, although the upholstery was new (and has been replaced twice since 1952, the leather acquired from the official upholsterer to Parliament.) The Minton tile surround from the fireplace was apparently removed in late 1953. Bossom had been asked to look for a suitable fireback for the fireplace and he wrote to Mrs. Mitchell on December 7, 1953: “[Is] the tile facing still on the fireplace in the English Room? I have pictures both with it and without it and, of course, this does make a tremendous difference to the type of fireback I get.”[16] The fireback Bossom found “dated 1858, cast in commemoration of the defeat of the Spanish Armada.”[17]

On July 4, 1956, Bossom wrote to Mrs. Mitchell:

You have today actually in Pittsburgh more of the original materials from the old House of Commons that exists anywhere else in the world. That fireplace is quite unique and the paneling too is remarkable. As to the various pieces of material that have been added, like the fireback and the cartouche over the doorway and in fact all of the things sent over, these are absolutely unique.[18]

Pugin’s Legacy

The two great rules for design are these: 1st, that there should be no features about a building which are not necessary for convenience, construction or propriety; 2nd, that all ornament should consist of the essential construction of the building. The neglect of these two rules is the cause of all the bad architecture of the present time.

“The True Principles of Pointed or Christian Architecture,” 1841

Pugin placed Gothic architecture and craftsmanship squarely in the forefront of 19th-century design, informing the sensibilities and the work of countless later architects and artists. In 1888, Arts & Crafts architect John D. Sedding stated: “We should have no Morris, no Street, no Burges, no Shaw, no Webb, no Bodley, no Rossetti, no Burne-Jones, no Crane, but for Pugin.” In 1904, Hermann Muthesius wrote in his monumental book, The English House: “Looking back today at the achievement of the Gothicists in the field of artistic handicrafts, one can have no doubt that Pugin’s work stands supreme.”

For the next sixty-seven years, architects and architectural historians in Europe, Britain, and the United States turned their attention to the contemporary functionalism of the International Style and much nineteenth-century architecture and design was ignored. In 1971, however, the Victoria & Albert Museum devoted a significant section of an exhibition on Victorian Church Art to Pugin and in the USA Professor Phoebe Stanton of Johns Hopkins University published the first substantial study of Pugin’s life and work in the twentieth century since Muthesius’ 1904 study.

Pugin’s stature was emphatically reaffirmed in 1994 when the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, held an exhibition, Pugin: A Gothic Passion (June 15-September 11). As the catalogue, published by Yale University Press, stated: “This book is the first to offer a complete appraisal of Pugin’s life and achievements; it is published to accompany the first major Pugin exhibition ever mounted. . . . It contains twenty-one essays by international scholars and specialists, who discuss in detail the many aspects of Pugin’s life and career. The superb photography has been specially commissioned, and includes numerous objects and buildings never before reproduced.” Co-editor Clive Wainwright wrote in his essay “ ‘Not a Style but a Principle’: Pugin & His Influence” that “both in architecture and the applied arts Pugin’s principles were to underpin the whole of the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain and America.” Pugin: A Gothic Passion inspired another major exhibition (and catalogue also published by Yale University Press), A. W. N. Pugin: Master of Gothic Revival, held at the Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts, New York City (November 9, 1995-February 25, 1996). A 5-volume critical edition of Pugin’s letters (2001-15), a new critical biography (2007), and a major study of Pugin’s stained glass designs (2009) have appeared.

In 2002 I ended my article “Treasure in the Cathedral” as follows:

In Pittsburgh, architecture and decorative arts rooted in medieval design and craftsmanship flourished in the 1840s—John Chislett, Joseph Kerr, John Notman—through the 1880s and 90s—H. H. Richardson, John Evans, William Halsey Wood, Frank Furness—to the 20th-century: Franz Aretz, John T. Comes, Charles J. Connick, Ralph Adams Cram, Bertram G. Goodhue, Harry E. Goodhue, Wright Goodhue, William P. Hutchins, Henry Hunt, Albert F. Link, John Kirchmayer, Charles Z. Klauder, Leo A. McMullen, William R. Perry, E. Donald Robb, Lawrence Saint, George and Alice Sotter, Carlton Strong, Samuel Yellin, Edward J. Weber, Howard G. Wilbert, William and Anne Lee Willet—to name the best known.

It is therefore appropriate—indeed, rather humbling—to discover Pugin in Pittsburgh, and to know that fragments of the work of this brilliant designer and ardent theorist are preserved in the English Nationality Room in the Cathedral of Learning.

In June 29, 2015 I was invited to the English Nationality Room to look at an odd object that had been found at the rear of a closet. It was Pugin’s Aye Lobby fireplace Minton tile surround, where it had been stashed away for the past sixty years, a casualty of a mis-guided and mis-informed historicism. We now know that the most important elements in the English Nationality Room are the elements designed by A. W. N. Pugin for the House of Commons and the most important of these is the Minton tile fireplace surround.

Select Bibliography

“A. W. N. Pugin.”Victorian Church Art. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1971: 7-21.

Stanton, Phoebe. Pugin. New York: The Viking Press, 1971.

Atterbury, Paul, and Clive Wainwright, eds. Pugin: A Gothic Passion. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994.

Atterbury, Paul, ed. A. W. N. Pugin: Master of the Gothic Revival. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

Pugin, A. W. N. The Collected Letters of A. W. N. Pugin. Volume 1-5: 1830 to 1852.

Ed. by Margaret Belcher. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001-2015.

Tannler, Albert M. “Treasure in the Cathedral.” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review Focus 27:48 (October 6, 2002): 8-10.

Tannler, Albert M. “Pugin in Pittsburgh.” PHLF News 163 (February 2003): 16.

Hill, Rosemary. God’s Architect: Pugin & the Building of Romantic Britain. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007.

Shepherd, Stanley A. The Stained Glass of A. W. N. Pugin. Reading: Spire Books Ltd., 2009.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to E. Maxine Bruhns, Nationality Room Director; Maryann Sivak, Assistant to the Director; Michael Walter, Nationality Rooms Tour Coordinator; and Max Adzema, research assistant. Zachary L. Brodt, University Archivist, University of Pittsburgh, facilitated my research in the English Nationality Room Committee Collection, 1929-1981.

[1] This essay is a revision and expansion of “Treasure in the Cathedral,”Pittsburgh Tribune-Review Focus 27:48 (October 6, 2002): 8-10. See also my article “Pugin in Pittsburgh,” PHLF News 163 (February 2003): 16.

[2] Two other Nationality rooms with genuine historical elements and character are the Syrian-Lebanon library (1782) and the Croghan-Schenley ante-room and ballroom (1835).

[3] James Stevens Curl, Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006: 793.

[4] Curl, 571.

[5] Ruth Crawford Mitchell to Alfred Bossom, February 6, 1948, English Nationality Room Committee Collection, 1929-1981, UA.40.07, University Archives, Archives Service Center, University of Pittsburgh [Vol II].

[6] The English Room in the Cathedral of Learning: Revised Memorandum on Design proposal on the basis of conference and correspondence with Alfred C. Bossom, M.P., Architect A. A. Klimcheck, University Architect, and John Weber, Secretary of the Board of Trustees (November 2, 1950). [English National Room Committee Collection, III].

[7] R. C. Mitchell to A. Bossom, February 20, 1951 [Vol. II[

[8] R. C. Mitchell to A. Bossom, February 23, 1951 [Vol. II]

[9] Memo from R. C. Mitchell to Chancellor R. H. Fitzgerald, July 6, 1951 [Vol. II]

[10] Original has 1934, which is clearly a typo.

[11] A. Bossom to James Robinson, British Consulate General, Philadelphia, Pa., May 1952 [Vol. II]

[12] A. Bossom to R. C. Mitchell, May 9, 1952 [Vol. II]

[13] R. C. Mitchell to A. Bossom, May 21, 1952 [Vol. II]

[14] A. Bossom to R. C. Mitchell, July 7, 1952[Vol. II]

[15] These shards of glass were reconfigured as medallions by James Powell & Sons, London. Other medallions were made by Hunt Stained Glass Studio, Pittsburgh.

[16] A. Bossom to R. C. Mitchell, December 7, 1953 [Vol. II]

[17] Chancellor Fitzgerald to A. Bossom, December 22, 1953 [Vol. II]

[18] A. Bossom to R. C. Mitchell, July 4, 1956 [Vol. II]