Architectural Glass in Pittsburgh

Series 3: Classical Perspective, Industrial Art, and American Gothic

Albert M. Tannler, Historical Collections Director, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation (1991-2019)

Delivered at the First Baptist Church, Pittsburgh, June 21, 2009, as the second event in Charles J. Connick: World-Class Stained Glass in Pittsburgh, offered by the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation in cooperation with First Baptist Church and The Charles J. Connick Stained Glass Foundation, Ltd.

INTRODUCTION

The First Baptist Church, designed by Bertram Goodhue of the New York Office of Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson, was dedicated April 28, 1912. The following October Architecture magazine stated that First Baptist “is, of all the work of this firm which has so far been constructed, the most interesting and the most beautiful, and its interest is due very greatly to the fact that it is to such a slight extent traditional and to such a great extent original . . . . It is genuine modern architecture.”

One month earlier an article on the building appeared in the September issue of Architectural Review. Regarding the large clerestory windows—clerestory windows are a row of upper windows—the author, architect Arthur Byne, wrote:

These clerestory windows occupy the whole bay as do those in fully developed Isle-de-France Gothic. . . . . Neither English nor French, but wholly modern, is the way in which the wall arch of the vault and the inside arch of the window are fused together carrying Gothic construction to its logical issue . . . .

Although colored-glass windows had been known since antiquity in various places and in a variety of forms, one can argue that the stained glass window reached an unprecedented and extraordinary level of technical and artistic achievement in 12th-century Europe. Cathedral builders were able to create window openings of unparalleled size and challenged and inspired glass artists to new levels of creativity—and vice versa. As Robert Scott notes in his study of Gothic cathedrals:

In dramatic contrast to the [Romanesque] style, the walls of Gothic cathedrals appear almost porous. Light permeates the interior and merges with every aspect of it, as though no segment of inner space should be allowed to remain in darkness, undefined by light. . . . The medieval builders’ ideal is exemplified by the interior of Chartres or Canterbury Cathedral, where the glass is colored in deep primary tones. As a result, even though the interiors are filled with light, the spaces acquire deep and rich color tones. The attempt to combine these two things—increased light and deep color—impelled the builders to reach for greater and greater heights.

Arthur Byne called the First Baptist windows “wholly modern” masterpieces of 20th-century architectural design. Yet they are rooted in architectural forms whose materials and techniques were developed some 800 years ago. The architectural style of this building is generally known as “Gothic,” a term adopted in the 17th century. In the 12th-century, when it first appeared, it was initially called “opus modernus.”

How is it that an art form, born in 12th-century Europe, appears in the 20th-century in the United States? This country was not colonized by Europeans until the 17th-century and not formally established as a nation until the 18th century—a nation, in other words, that came into being during a period of architectural classicism. Indeed, architectural historian and curator Barry Bergdoll observed that the United States is “the only independent western . . . nation . . . with no Gothic past.”

During the 18th-century “Age of Enlightenment”—in Britain, despite its Gothic past, and in America—glass historian James Sturm reminds us: “Public buildings and churches in both England and the Colonies increasingly were glazed only with clear glass . . . . The magical colored windows of the medieval cathedral were rejected along with all the rest of what was considered to be darkness and superstition of medieval life.”

A Gothic revival began in England in the 1830s, instigated by Roman Catholic architect Augustus Pugin, and adopted by the Anglican Church of England. Its impact at this time in the United States was minimal. Roman Catholic immigrants from Italy and Eastern Europe, heirs to Mannerist and Baroque Classicism, were often indifferent to Gothic art and architecture, while those from Ireland came to see it as representative of a repressive English establishment. In 1773 when the First Presbyterian Church was established in Pittsburgh, much of Western Pennsylvania was still on the frontier, and was a bastion of Scots-Irish Presbyterianism. Stained glass windows, especially figural windows, were considered idolatrous; they were so considered in some Presbyterian churches as late as 1910.

I. Classical Perspective

The Classical architecture of the 18th-century American colonies and new nation was derived from the architecture of ancient Greece and Rome and was called “Georgian” after the kings of England and later “Federal” after the new nation. During the early years of the 19th-century, Roman architecture took precedence; later, Greek. The fledgling nation looked to these ancient societies as possible role models; indeed, Greece supplanted Rome when Rome’s transition from democracy to imperial empire came to be seen as an uncongenial precedent.

In France another revival of Classical architecture and design was becoming prominent. The Classical Greco-Roman architectural vocabulary as revived and reinterpreted during the Italian Renaissance, roughly 1400 to 1580, underlay the curriculum of the École des Beaux-Arts, or School of Fine Arts, in Paris. Richard Morris Hunt was the first American to study architecture there, from 1846 to 1855; he later trained architects in his New York studio according to École principles. Hunt’s student William Ware established the first U.S. school of architecture in 1867 at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This curriculum was adopted by most of the American architectural schools founded thereafter through the early years of the 20th-century.

Many American painters and sculptors also went to Paris to study at the School of Fine Arts or in the atelier or studio of a prominent French artist.

In 1876, the United States celebrated its Centennial with a great Exposition in Philadelphia; many of the buildings paid tribute to the architecture of the 1770s and reminded attendees of America’s classical past. The following year, in 1877, Richard Morris Hunt began to design a series of Renaissance-inspired mansions for the Vanderbilt family in New York City, Newport, Rhode Island, and North Carolina.

In 1880 a new term appeared in architectural publications—“American Renaissance”—and it gave a name to an era that lasted through World War I. During the years of the American Renaissance the United States became a world power, its population changing from rural to urban. Americans were growing confident, but were still unsure of America’s cultural status among nations. They looked to the 15th-century revival of “Classical” architecture and art, and to its inventiveness, erudition, and vigor, as the model best suited to realize their own aspirations. The American Renaissance, one historian has noted, “proclaimed that a new society based on science, industry, commerce, rational order, democracy, and the great energy of the people had been forged and was the legitimate heir to the concept of the Renaissance.”

The first prominent public building in a Renaissance style in the United States was The Library of Congress; the Library was designed in 1886 and construction began in 1889. Another milestone in American Renaissance architecture was the Boston Public Library, designed by McKim, Mead & White of New York and begun in 1888. While these buildings were under construction and before their interior decoration began, the World’s Columbian Exposition opened in Chicago in the Fall of 1892. The opening ceremony was brief, since the World’s Fair buildings were not finished; the public opening took place in 1893. The leading architects of the country were gathered under to direction of Chicago architect Daniel H. Burnham to design a great American Renaissance assemblage of buildings, decorated by the country’s leading artists.

Decoration of The Library of Congress and the Boston Public Library began in 1893 and many of the American-born, Paris-trained artists who decorated these buildings had worked on the buildings at the Chicago Fair. The Library of Congress opened November 1, 1897. Historian Pierce Rice has written: “The World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 had provided the example of painter, sculptor, and architect working side by side. The Library of Congress was the first great building that sprang out of the Chicago vision, to be followed by heroic civic projects.”

In 1901, Mrs. John A. Logan wrote in her memoir of life in Washington: “The new Library of Congress is a monument of a nation which has emerged from the darkness of doubts and dangers into the full glory of conscious power. Every stone in the Capitol was the promise of a nation yet to be; every stone in the Library of Congress is the symbol of fulfillment.”

One artistic expression of the American Renaissance was the invention of a new colored window glass. New Yorker John La Farge, a Paris-trained painter and muralist, interior decorator, art critic and scholar, and the first important collector of Japanese art in the United States, invented opalescent window glass by combining milky, iridescent opal or milk glass, with molten colored glasses, rolled into large sheets. Glass historian Julie Sloan notes: “Opalescent glass has a milky opacity created by the suspension of particles that reflect and scatter light. While the material had been in use for tableware . . . for decades, it had never before been made into flat sheets for use in windows.”

As La Farge stated in his 1879 patent application, his invention enabled him “to gain effects as to depth, softness, and modulation of color [and] gain great advantage as to realistic representation of natural objects.” This goal was derived from, and an extension of, Renaissance painting techniques. La Farge scholar Barbara Weinberg tells us that “La Farge sought to reconcile the color and brilliance of early glass with contemporary desires for naturalistic form . . . and the necessary sense of depth to permit depiction of rounded forms and convincing space.”

The strips of lead used to frame and connect panes of glass were now used only to outline figures, and perspective was achieved by layering panels of different colored glasses. Opalescent glass is iridescent and holds light; it is not transparent. A single pane may be richly multicolored and the lack of transparency made this an ideal glass for skylights and lampshades.

English critic Cecilia Waern published a monograph on John La Farge in 1896. She observed: “His very earliest windows are purely ornamental: one of the first he made is based on Japanese metal open work, in which the leads form the decorative basis. Soon afterwards he began to show his intimate alliance with the feeling of the Renaissance.” La Farge’s mature windows are derived from Classical Renaissance iconography. Frequently his figures are framed by Classical columns and Greco-Roman decorative forms such as Greek fret and dentil patterns, as in his 1902 Fortune window in Pittsburgh’s Frick Building.

La Farge’s opalescent glass patent was granted February 24, 1880. La Farge subsequently discussed his invention with Charles Tiffany, proprietor of Tiffany & Co., and Charles’ son, Louis, proprietor of the interior decorating firm, L. C. Tiffany Co. Writer and glass enthusiast Roger Riordan noted in his 1881 essay “American Stained Glass”: “Mr. La Farge has taken out patents for the manufacture of ‘opal’; it is also largely used by the firm of Louis C. Tiffany & Co., associated artists, under Mr. La Farge’s patent.” Louis Tiffany subsequently applied for his own opalescent window glass patent, which was granted in 1881. La Farge filed a lawsuit against Tiffany for patent infringement, but lacking the Tiffanys’ financial resources, he dropped it.

During the period of the American Renaissance, opalescent glass was known throughout the world as “American Stained Glass” or just “American Glass.” Since the 1960s, opalescent glass has been widely and incorrectly called “Tiffany” glass, whether or not it was produced by or for Louis Tiffany’s glass company. Tiffany first sold glass windows in 1880; he opened his own glass-making plant in 1892, he retired in 1919, and his firm went bankrupt in 1932. His father’s firm, Tiffany & Co., is still in business and did not make stained glass windows.

By 1890 and through circa 1915, almost all American glass studios used opalescent glass as their primary material and sought to create windows that mimicked the Classical idealism and naturalistic perspective first explored in Italian Renaissance painting. Such naturalistic visual art—both idealistic and realistic—would have seemed quintessentially modern. At the same time, its naturalistic depiction of Bible stories appealed to churchgoers. Even prestigious Presbyterian churches embraced the medium. In 1903, The Presbyterian Banner wrote about the windows at the new Third Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh:

In the history of churches of all denominations in this country there has been no period that has shown such a marked growth and development of the love of the beautiful in their enrichment and adornment as within the past quarter of a century. . . . With the development of art education, . . . linked with a higher appreciation of the possibilities of Scriptural interpretation through its medium, there began an enrichment of houses of divine worship irrespective of previous denominational tradition. . . In ecclesiastical decoration there is no more effective feature, nor one which embraces such a wide range of Scriptural teaching in a pictorial sense than the stained glass window.

Although Tiffany set up his own glass factory, directed by Englishman Arthur Nash, most studios purchased their glass from glass makers such as Louis Heidt of Brooklyn, Decorative Stained Glass Company in New York City, and Kokomo Opalescent Glass Company, Kokomo, Indiana, founded in 1888 and still in business.

Many Americans aspired to be painters, but after studying in Paris, returned to the United States and began to work in glass, often as employees of interior decorating firms such as those established by La Farge and Louis Tiffany. Among the most important of these artists are Sarah Lyman Whitman of Boston; George Healy and Louis Millet of Chicago; David Maitland Armstrong, Mary Elizabeth Tillinghast, Edward Peck Sperry, Clara Miller Burd, and members of the family that operated the J. & R. Lamb Studio, all of New York. Except for Mrs. Whitman, we have work by all the others in metropolitan Pittsburgh.

Some Parisian-trained artists were primarily painters and muralists who occasionally made designs for glass windows: Will Low, Elihu Vedder, Kenyon Cox, Violet Oakley, and Herman Schladermundt are among the best known. More than a few artists, some Paris-trained and some not, worked for John La Farge: Low, Tillinghast, Joseph Lauber, Roger Riordan, and Jacob Holzer. Low, Lauber, and Holzer (sounds like a law firm!) would later work for Tiffany. We have windows by Kenyon Cox and Herman Schladermundt in Pittsburgh. William Willet, who worked in John La Farge’s studio from 1885 through 1887, was active in Pittsburgh from 1897 to 1913.

Does this suggest a crowded playing field rather than a one-man show? Indeed it does. It demonstrates that the overwhelming majority of American artists and firms worked in opalescent glass during the American Renaissance.

In 1900 in Pittsburgh—then acknowledged as a center of business, industry, and, yes, culture—15 glass firms vided for customers for opalescent windows for residences, schools, libraries, government buildings, commercial buildings—as well as churches. Among the leading local firms was Rudy Brothers, established in 1893. Artistic director J. Horace Rudy trained some of the most prominent stained glass artists in this country—George Sotter and his wife Alice both apprenticed at Rudy Brothers and subsequently worked as a team, Lawrence Saint became head of the stained glass workshop of the National Cathedral in Washington, and, preeminently, Charles Connick whose stained glass was acclaimed internationally. William Willet and his wife and partner Anne Lee Willet, who got equal billing, arrived in Pittsburgh in 1897 and established The Willet Stained Glass Company in 1899. Leake & Greene established their firm in Boston, then moved permanently to Pittsburgh in 1894; their glass artist, Henry Hunt, left in 1906 to establish his own Pittsburgh firm, now 103 years old.

II. Industrial Art

And so we return to Tiffany, whose name everybody knows. Louis Tiffany was born with financial and artistic advantages. His successful and socially prominent mercantile family could afford to support his artistic training and extensive travel. Many of his father’s customers became his as well.

One influence on Louis’ artistic sensibility was Edward Moore (1827-91), chief designer from 1868 to 1891 of Charles Tiffany’s silverware and jewelry store, Tiffany & Co., founded in New York City in 1837. Moore was an avid collector of Japanese and Islamic art.

Louis studied painting in Paris with Leon Belly, best known for exotic Oriental paintings such as Pilgrims Going to Mecca, Interior of the Harem, and By the Nile. Tiffany traveled throughout Europe, and visited North Africa, which particularly intrigued him. Back in New York, Tiffany joined textile artist Candace Wheeler and decorator Lockwood de Forest in a series of interior decorating ventures beginning in 1879. Tiffany’s interest in the business of art is shown in a letter he wrote to Candace Wheeler about the new venture: “It is the real thing, you know; a business not a philanthropy or an amateur educational scheme. We are going after the money there is in art, but the art is there, all the same.”

Meeting John La Farge and learning about his glass experiments, moved Tiffany’s interest in glass to the forefront, and in 1880 he asked David Maitland Armstrong to design windows for Tiffany’s decorating firm. In his pioneering 1881 essay, “American Stained Glass,” cited earlier, Roger Riordan evaluated Tiffany’s artistic approach:

Mr. Tiffany’s Oriental leanings are well-known. He is in favor of the boldest, strongest, most telling method. He never hesitates to join cloth of gold to cloth of frieze [heavy rough woolen cloth], to inlay rough-cast with fine marbles, or to use the cheapest along with the most gorgeous glass, when an artistic result may be secured. He is without any touch of the “literary sort of thing.” He speaks, as nature does, through the eye to the mind and the feelings . . . .

In 1885 Tiffany’s firm became Tiffany Glass Company, then Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company (in 1892), and finally Tiffany Studios (in 1902).

Windows by La Farge and Healy & Millet were the first American opalescent windows awarded gold medals at an international exposition—in Paris in 1889. Tiffany’s display at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 brought him national acclaim and international attention.

In 1894, the French government sent art dealer Siegfried Bing to study the current state of the arts in America. Bing did not meet La Farge, but submitted a series of questions which La Farge answered in a letter. Bing did visit the Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company. In Artistic America, published in France in 1895, Bing devoted 3 paragraphs to La Farge and 19 paragraphs to Tiffany and enthusiastically described Tiffany’s New York studio in the chapter entitled “Industrial Art.” It was, Bing wrote, “a large factory, a vast central workshop that would consolidate under one roof an army of craftsmen … all working to give shape to the carefully planned concepts of a group of directing artists.”

Sometime after writing her book on La Farge, English art critic Cecelia Waern visited the Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company and described it in a two-part article, “The Industrial Arts in America,” in the English magazine The Studio. She wrote: “Tiffany’s main sources of inspiration have been Oriental and transitional styles that have something colouristic in their very treatment of lines and masses. He knows them well and uses them freely.”

Miss Waern contrasted what she called Tiffany’s “industrial art” with that of English Arts & Crafts. Neither Charles or Louis Tiffany, she wrote, “try to emulate Morris and Co. in educating the public taste; their aim is to sell, to persuade, not to elevate or instruct; there is also a tendency to simplify the labour expended, as far as possible, with a view to reducing the cost of production.”

Regarding the workforce she observed: “At present there are from forty to fifty young women employed in the glass workshop, working at either mosaic or windows, generally ornamental. The larger memorial windows are, as a rule, put together by men (in other workshops).”

Concerning the character of ecclesiastical windows she noted:

The Tiffany ecclesiastical work certainly does not err on the side of baldness, as all will remember who saw the World’s Fair chapel with its sumptuous wealth of Tiffany Byzantine in mosaic, scroll borders, gorgeous hanging lamps, and marble inlays. The effect was to many, indeed, over-ripe and heavy, with a tendency to somewhat cloying sweetness.”

Nonetheless, she admired much of Tiffany’s work and enjoyed his frenetic energy, suspecting that he regarded, in her words: “the workshops as nothing but a splendid opportunity for trying experiments on a large scale.”

As stated earlier, since the 1960s there has been a renewed interest in Louis Tiffany and many books, articles, and exhibition catalogs have been published. Initially, extravagant claims were made; more recent studies have provided accurate documentation and more balanced views. The interpretive problems can largely to traced to Tiffany himself and any examination of American stained glass windows must contend with his self-generated legend; this requires, regrettably, some effort and much time, before the story of stained glass in America can be continued.

Let’s take a look at Tiffany’s iconographic program; in other words, his visual language. His contemporaries noted his interest in forms derived from nature; his exotic “Oriental” imagery, more Middle Eastern than Asian; and his flamboyant use of colors and materials.

We should note that Tiffany’s stained glass studio soon added a line of lamps, then glass objets, then metalwork. Perhaps the most salutary influence on Tiffany came from French Art Nouveau, in particular, Emile Gallé who designed and made exquisite glass objects inspired by natural forms. Exotic influences and vibrant colors are often found in Tiffany glassware and metalware. And, as Cecila Waern noted, Tiffany’s opalescent windows “certainly do not err on the side of baldness.”

Tiffany windows remained within the Renaissance tradition, exhibiting perspective and three-dimensionality. As Martin Eidelberg has stated, somewhat acerbically: “Tiffany’s figure windows after 1900 still bore the dulling effects of nineteenth-century academic propriety, and certainly shunned all the modernistic elements of design that he could have learnt from [French painters Pierre] Bonnard and [Paul] Ranson.” Eidelberg further notes Tiffany’s “drive toward realism” and “absence of modernism of design.”

Our second question: to what extent was Louis Tiffany a stained glass artist? The answer may surprise you. Let us recall Siegfried Bing’s description of Tiffany’s studio: “a large factory, a vast central workshop that would consolidate under one roof an army of craftsmen … all working to give shape to the carefully planned concepts of a group of directing artists.” Although curator Hugh McKean clarified Tiffany’s role as early as 1980, the reality has often been overlooked. McKean stated: “Tiffany’s workshops, of course, made thousands of windows. A rare few were made from his own designs. Most were from designs by artists on his staff.”

David Maitland Armstrong (1836-1918), who designed Tiffany’s first commercial opalescent glass windows, worked for Tiffany from 1879 to 1887. Armstrong was succeeded by Swiss-born Jacob Holzer (1858-1938), who joined Tiffany in 1888 and held the position of chief window designer from 1890 until 1896. Holzer was succeeded by Frederick Wilson (1858-1932) who was chief designer for 27 years, longer than anyone else. He left Tiffany’s firm around 1923. Wilson’s Tiffany windows may be seen at First Lutheran, First Presbyterian, and Third Presbyterian in Pittsburgh.

The chief window designers supervised the artists who designed most of the firm’s windows. Two of the most talented window designers were Agnes Northrup (1857-1953), who joined the firm in 1884 and created the first landscape windows and did so throughout the firm’s existence, and Edward Peck Sperry (1850-1935), who entered the firm around 1888 and remained until 1902; he designed the Tiffany windows at Calvary Methodist and First United Methodist churches in Pittsburgh. Other well-known painters, as mentioned earlier, were hired to design glass on a free-lance or part-time basis.

Executing a Tiffany window also involved glassmakers, glasscutters, artists who specialized in painting hands and faces, “builders” who assembled the windows, and crews of installers who set them in place.

One of the most recent studies of Tiffany’s firm was published in 2007 and uses newly discovered material documenting the career of Clara Driscoll, who designed some of the most famous Tiffany lamps between 1888 and 1909. The authors tell us:

[M]ost Tiffany employees worked anonymously. Although he occasionally credited the designers of his firm’s windows and mosaics, Tiffany preferred that his name alone appear before the public. His advertisements . . emphasized how he himself had labored to perfect the richly colored iridescent glass that was his invention. . . .

As we know, Tiffany did not invent opalescent glass. The text continues:

When the firm was obliged to disclose the names of individual workers to juries, as at the Paris World’s Fair of 1900, it complied and, in fact, both Clara [Driscoll] and Arthur Nash [head of Tiffany’s glass works] as well as others received prizes. Nonetheless, their individual awards were never publicized but Tiffany’s were.

I cannot count the number of well-intentioned people who know that Tiffany personally made the windows in their church, or who insist that all Tiffany windows have an unmistakable “look” that only he could impart. These misconceptions result from what has been called “a brilliant and typical display of showmanship” and explain why the Tiffany name is ubiquitous.

Louis Tiffany exhibited sketches for window designs in the 1880s and 90s when his firm exhibited at the Architectural League of New York, but the majority of the designs were by other artists. Tiffany designed some windows, and he would have supervised, to some extent, the most important realized commissions. His artistic role was primarily visionary and entrepreneurial.

With the exception of a few already established artists, Tiffany’s staff was only mentioned by name when outside parties intervened. The best writers on Tiffany have understood this. In 1982 James Sturm wrote, in what is still the best overview of stained glass in America, that the finest Tiffany windows “testify to the talent, lost in the shadow of their employer’s reputation, of the designers and craftsmen at Tiffany Studios.”

Louis Tiffany created a brand name, and generations of museum curators and gallery owners have been more than willing to increase the economic value of the art works designed and made by his employees.

Tiffany transformed the Renaissance workshop, and its successor the 19th-century atelier, into an American factory. Tiffany is inaccurately identified with the Arts & Crafts movement when in fact his mechanized glass-making process and his hierarchical division of labor are its antithesis. He is mistakenly celebrated as a Modernist although there is nothing modern, that is, abstract, about his artwork, while he himself denounced modern art. Changes in artistic taste and the Depression ended his career.

Although Tiffany wasn’t a Modernist, there is something in his Renaissance-derived approach that appeals to the 21st-century American art market. In 2006, an article appeared in the arts section of The New York Times titled “Looks Brilliant on Paper But Who, Exactly, Is Going to Make It?” It said in part:

Artists have relied on the aid of apprentices, artisans and studio assistants for centuries. Raphael, Titian, Rubens and Rembrandt all presided over busy workshops where apprentices churned out paintings to which the master would add finishing touches—and his signature. What has changed is the expectation that artists actually possess the skills to produce their own work.

The article quotes a prominent New York gallery owner: “We’re in a post-Conceptual era where it’s really the artist’s idea and vision that are prized, rather than the ability to master the crafts that support the work. Today our understanding of an artist is closer to a philosopher than to a craftsman.”

III. American Gothic

So we are back at First Baptist and the paradox of “genuine modern architecture” with “wholly modern windows” based on 800-year-old forms.

“What does this mean?” Or perhaps: “How did this happen?”

It was the arrival of the Expressionist, Primitivist, and Abstract art movements in the teenage years of the 20th century and the reshaping of the architectural curriculum under the influence of German and French architects and theorists beginning in the 1920s that led to widespread objections to any use of the Western classical design vocabulary. After World War II this escalated, so much so that some historians ignored or denied America’s Classical heritage. One example is the recent objection to the design of the World War II Memorial in Washington—Nazi Germany! Fascist Italy!—were evoked by critics blind to the myriad American Renaissance buildings in the nation’s capitol and throughout the country. Venerable non-Western architectural vocabularies have been permitted since they are by and large not recognized as “classical,” but newspaper writers on design still bristle at the sight of Western classical forms on contemporary buildings.

If classical forms refuse to die in the USA, much to the annoyance of some, Gothic architectural forms have been perceived to be irrelevant, and hence, non-threatening. Interest in such forms is relegated to a small “religious” segment of the population.

I earlier mentioned the Gothic Revival in England in the early 19th-century. This movement did influence some architects in the United States. Andrew Jackson Downing’s pattern books of 1842 and 1850, Cottage Residences and The Architecture of Country Houses, placed Gothic dwellings—and the equally exotic Swiss Chalet—on an equal footing with Classical Greek, Italianate, Second Empire, and Queen Anne designs. Thus Gothic became one of several equally popular “picturesque” styles. Some handsome Gothic churches, modeled after those in England, were designed by James Renwick, John Notman, and Richard Upjohn for a limited constituency, usually Episcopalian. Nonetheless no American architects possessed the single-minded allegiance to Gothic forms that we find in English architect Augustus Pugin and his many successors.

I should also note that late medieval elements are found in 17th–century American domestic architecture. Antoinette Downing and Vincent Scully observe that “the houses and meeting houses of seventeenth-century Newport were built by carpenters who . . . followed medieval building methods.” These buildings were “a later afterglow of Gothic tradition on colonial soil. They [had] great exposed hewn beams, huge space-consuming chimneys and fireplaces, steeply pitched roofs, small leaded casement windows.” The beams, fireplace inglenooks, and casement windows were subsumed into 18th-century design and re-emerged in American “Shingle Style” and Craftsmen houses.

Such fragments aside, the United States had no indigenous Gothic tradition of design and building. English historians have noted this; Isabelle Anscombe and Charlotte Gere wrote in 1978: “Americans had not had an identifiable Gothic Revival of their own.” Perhaps the only American historian to both state and sharpen this perception is Barry Bergdoll, now architectural curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, who wrote in 1995: “The United States is the only western . . . nation with no Gothic past.” It is therefore inexact, indeed, incorrect to speak of an American Gothic “Revival”; as we had no Gothic past, there was no Gothic to “revive.”

Medieval design entered the architectural vocabulary of the United States thanks to two larger-than-life individuals, one English—William Morris; the other American—Henry Hobson Richardson.

Remember Cecelia Waern’s assessment that Charles and Louis Tiffany “certainly do not try to emulate Morris and Co in educating the public taste; their aim is to sell, to persuade, not to elevate or instruct; there is also a tendency to simplify the labour expended, as far as possible, with a view to reducing the cost of production.”

William Morris (1834-96) apprenticed briefly in an architectural firm, was a painter; a designer of furniture, glass, textiles, and books; a poet and novelist; a social activist, indeed, a social revolutionary; and, as founder of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings in 1877, a pioneering preservationist. His firm, Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., was founded in 1861 and became Morris & Co. in 1875. Morris deplored the cheap machine-made goods and the dehumanizing division of labor prevalent in his industrialized society. Influenced by John Ruskin’s interpretation of Gothic art and labor, Morris looked to the Guilds of the Middle Ages as models for social equality and artistic achievement. Through his company, Morris sought to produce quality work, often using traditional—“natural,” if you will—ingredients, and handcrafted methods. He advocated the equality of the decorative arts with the fine arts. English historian Alan Crawford notes: “Morris’ attachment to the old ways of working is often presented as ideological. It was also technical; he was a manufacturer getting things right.”

William Morris understood that the great glass windows of the 12th century were a technically and architecturally sophisticated achievement that could be revived but should not be drastically changed. He wrote in 1890: “This art . . . is especially an art of the middle ages; there is no essential difference between its processes as now carried on and those of the 12th century; any departure from the medieval method of production in this art will only lead us astray.”

In 1883, Morris & Co. exhibited some windows in Boston and provided a pamphlet that described their character:

Glass-painting differs from oil-painting and fresco, mostly in the translucency of the material and the strength, amounting to absolute blackness of the outlines. This blackness of outline is due to the use of lead frames, or settings, which are absolutely necessary for the support of the pieces of glass if various colours are used. . . . Absolute blackness of outline and translucency of color are then the differentia between glass-painting and panel or wall-painting. They lead to treatment quite peculiar in its principles of light and shade and composition.

Windows transmit light into a building; that is their primary architectural function. Morris believed that the glass must be made the traditional, medieval way: each color hand-blown into a tube, then flattened and cut into pieces. The lead framing the pieces of colored glass both support the glass and help focus the light and sharpen the colors. “It is highly desirable to break up the surface of the work by means of them,” Morris wrote, as they intensified “pieces of exquisite color.” Morris’s figures are, like the window itself, two-dimensional. What Morris & Co. called glass-painting refers to the use of a black ink-like compound to outline heads and hands and garments, provide shading, and create text.

In the 1870s Boston architect Henry Hobson Richardson (1838-1886) began to adapt 11-century Romanesque architectural forms and materials with such skill and flexibility that his buildings created a bridge between medieval and American design and produced some of the most powerful and imaginative buildings in 19th-century America. Richardson’s massive yet simple stone and brick government buildings, commercial buildings, residences, libraries, hospitals, churches, schools, train stations, and bridges, with their fanciful carving and decoration, brought medieval architectural forms into the American design vocabulary for the first time in a substantial way. Richardson’s Romanesque was the principal American expression of the revival of the art of the Middle Ages championed in England by John Ruskin, William Morris, and Morris’ Arts & Crafts successors.

Morris was the progenitor of the Arts & Crafts movement, which historian Peter Cormack has called “the only significant art movement to be wholly initiated in Britain.” Morris encouraged and employed younger artists and participated to some extent in the activities and publications of the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society, founded in 1888. But he also kept his distance, coming to believe that the only remedy for social inequality was the destruction of the industrial economy.

The term Arts and Crafts as used in the United States has become so broad and undefined as to be virtually meaningless. So let me be succinct: the American movement is about the customer; the original British movement is about the worker: “the decorative artist in his studio, the craftsman in his workshop, negotiating daily with materials,” in Alan Crawford’s evocative phrase. The Arts & Crafts movement was intrinsically preservationist, affirming the vitality of past verities in the present. Its adherents would have found the assertion that the past has no relevance for the present or the future to be psychologically and, indeed, technologically, naïve. Morris and his followers sought to revitalize traditional ways of working that engaged the worker and his or her skills, so that work would be humanizing and restorative.

Christopher Whall (1849-1924) of London, inspired by William Morris’s revitalization of medieval crafts, became the leading English Arts & Crafts glazer. Whall’s 1905 book Stained Glass Work is the definitive Arts & Crafts glass textbook. It was typical of Whall that he would warn his readers: “the worst thing that could happen to you would be to suppose that any book can possibly teach you any craft, and take the place of a master on the one hand, and of years of practice on the other.”

Whall criticized the Renaissance-derived desire to turn windows into naturalistic pictures “where the lead-line is disguised or circumvented,” noting that stained glass windows should remain windows: “Keep your pictures for the walls and your windows for the holes in them,” he wrote, adding: “a window is, after all, only a window . . . and nothing in it should stare out at you so that you cannot get away from it; windows . . . should be so treated as to look like what they are, the apertures to admit the light; Subjects painted on a thin and brittle film, hung in mid-air between the light and dark.”

Arts & Crafts artists deviated from Morris’ practice with one regard; while each Morris & Co. worker specialized in design or in one of the various tasks of fabrication, each Arts & Crafts artist, Whall wrote, “should be able to do the whole of the work oneself . . . There is not a touch of painting . . . which is not by a hand that can also cut and lead and design and draw, and perform all the other offices pertaining to stained-glass.” The ideal for Arts & Crafts artists was to work “with their own hands . . . designing only what they themselves can execute, and giving employment to others only in what they themselves can do.”

In England, the Gothic Revival gave birth to the Art & Crafts movement. In America, the British Arts & Crafts movement and the medieval architectural forms explored by Richardson provided the foundation for American Gothic architecture and design. The key figures of the American Gothic generation were Ralph Adams Cram (1863-1942), his partner, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue (1869-1924), and architects and artists they inspired or trained.

Ralph Adams Cram was particularly enthusiastic about the work of Christopher Whall and assisted in commissioning six windows from Whall for two Boston churches between 1906 and 1909.

Cram also encouraged and supported American craftsmen and artists. Some were immigrants, some native born. Cram worked with stone carver John Evans (1847-1923), who had worked closely with Richardson, and with wood carver John Kirchmayer (1860-1930), both founding members of the Society of Arts & Crafts, Boston; two other founding members were ceramicist and tile maker William Grueby (1867-1925) and stained glass artist Harry Eldredge Goodhue (1873-1918), brother of Cram’s partner, Bertram Goodhue. In addition to Harry Goodhue, Cram encouraged the work of stained glass artists Otto Heinigke (1850-1915) of New York and William Willet (1867-1921) of Pittsburgh. All but Heinigke have work at Calvary Episcopal Church, Pittsburgh. Sculptor Lee Laurie (1877-1963) began working for Cram and Goodhue in 1898; he frequently worked with Goodhue, carving, for example, the War Memorial at First Baptist. The woodwork at First Baptist is by the New York office of Irving & Casson, a firm established by Robert Casson, a founding member of the Society of Arts & Crafts, Boston. The chancel tile comes from Pewabic Pottery, established by Mary Chase Perry (1867-1961) in 1903 in Detroit.

Recitations of largely unfamiliar names can be numbing, so let me restrict the list to artists who worked with Cram in the 1930s on his two later Pittsburgh churches, Holy Rosary and East Liberty Presbyterian. In addition to English stone carver John Angel, we should note stained glass artists Wilbur Burnham, Sr.; Charles J. Connick; Nicola D’Ascenzo; Wright Goodhue, Harry Goodhue’s son; Oliver Smith, the son of Otto Heinigke’s partner; Joseph G. Reynolds and his partners William M. Francis and J. Henry Rohnstock; Howard Gilman Wilbert; and Henry Lee Willet, the son of William Willet. Cram’s patronage was multi-generational. As I have stated elsewhere: “It is largely due to Cram’s advocacy that the purity of colour and architectural fitness of the medieval stained glass window was widely accepted in the United States as an appropriate and indeed sophisticated element in a new architectural language based on ancient forms.”

If Christopher Whall was the principal English Arts & Crafts glass artist, then Charles Connick became the preeminent American Gothic glass artist. Connick was educated and apprenticed in stained glass in Pittsburgh and lived here for some 20 years. Cram and Connick met in 1909 in Boston. The artist showed the architect photographs of four windows from St. Mary’s Episcopal Church in Pittsburgh and the artist was hired to design and make a transept window for All Saints Episcopal Church, in the Boston suburb of Brookline. In rapid succession Connick quit his job, made the Brookline window at another studio, saw five of the six Christopher Whall windows in Boston and was awe-struck. He travelled to England to meet Whall and to look at English stained glass, and then visited Chartres Cathedral in France where he stayed for several months; the experience proved for him, as for many others, to be revelatory.

From about 1910 through 1913, Connick designed and made his windows at various Boston glass studios as an independent contractor. On April 22, 1913, Connick officially opened his own studio at 9 Harcourt Street in Boston. He organized it after Christopher Whall’s Arts & Crafts Studio which he had visited in 1910.

In the Connick Studio Records in the Fine Arts Department of the Boston Public Library there is a folder titled “Early Windows.” It contains copies of two typewritten lists; both are titled “Work Designed and Made by Charles J. Connick, Boston, Mass,” and dated August 20, 1913. One page is subtitled “Ornamental Windows” and includes 6 executed commissions. The other page is subtitled “Figure Windows, or Ornamental and Figure Windows Combined” and it includes 9 executed commissions. Each list has an asterisk beside jobs indicating “work of unusual importance.”

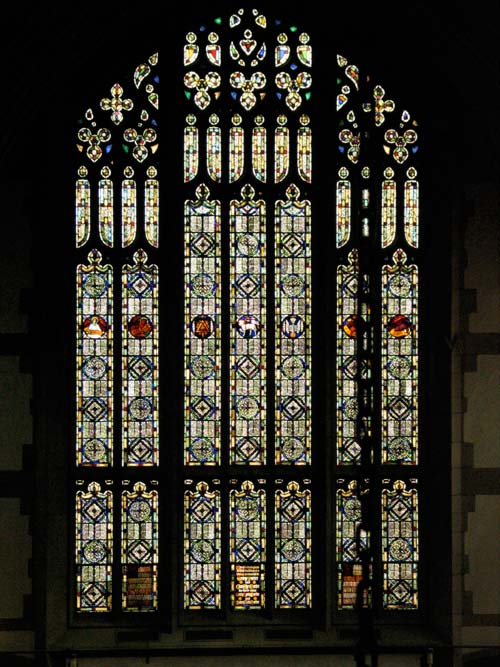

The list of “Ornamental Windows” designates four commissions as of “unusual importance.” These commissions are the chancel window at the First Unitarian Church, Chestnut Hill, Mass.; all the windows in Synod House at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City; all the windows in Fourth Presbyterian Church, Chicago (which were still being installed in August 1913), and, the first item on the list: “All windows in First Baptist Church, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” The commissions are not in chronological order. The First Baptist commission was the largest of Connick’s ornamental window projects prior to 1913. (The design of the blue-green panel behind the organ case, incidentally, is attributed to Bertram Goodhue.)

The ornamental windows at First Baptist are known as “grisaille.” Connick defined grisaille in a letter to a client:

The French word “grisaille” is translated “grayish.” It achieves a delightful luminous and colorful “gray” through the use of flowing patterns of paint over varying tints of glass that are interrupted by bands and spots of color—usually in a geometrical arrangement resembling what is ordinarily called an arabesque.

Grisaille windows had their origin under the monastic rule of Bernard of Clairvaux who considered vividly colored figural glass ostentatious.

It seems likely that Connick discovered grisaille in France, and it struck him as a wonderful opportunity to introduce a type of medieval glass to American churches as an aesthetically preferable and much less expensive alternative to opalescent windows. The qualities of grisaille glass are mentioned in Connick’s first article published in 1915:

Today many American churches are enriched by grisaille, wrought sympathetically in the exquisite textures consistent with its highest possibilities, and painted with due regard for varying intensities of light. Its cost is so moderate that, in many instances, a type of it is used for temporary glass, and thus the violent glare, so distasteful to architect and layman, is most pleasantly avoided.

A fascinating letter written five years earlier on December 21, 1910 by Ralph Adams Cram, however, makes clear how significant Connick’s revitalization of Gothic grisaille was—and would be—for American Gothic architecture and stained glass:

Dear Mr. Connick:

You asked me to say what I think of the results of your experiments in the production of grisaille glass. I have no hesitation in saying that the results you have achieved are far above anything I . . . supposed would be possible. . . .

Your real grisaille, which is really almost equal to the medieval product, is, in my opinion, ideal for permanent purposes, and its price brings it within the reach of almost everyone. . .

On the whole, I should say you had put both the Church and architecture in your debt by making it possible for both to obtain so absolutely beautiful and satisfactory a material.Very truly yours,

Ralph Adams Cram

Architect James McFarlan Baker, a member of Goodhue’s staff when First Baptist was designed and built, noted that the walls at First Baptist “seem almost literally walls of glass. Fortunately, it was possible to fill this with silvery grisaille of unusual quality.”

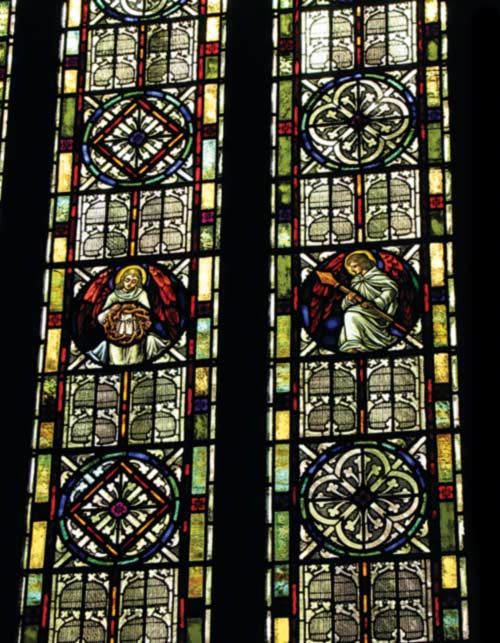

Sixty-seven colored glass medallions of angels and Christian symbols are set within the grisaille. It was almost certainly Charles Connick who described the windows as follows:

These windows have a remarkable quality of coloring and of light effect. The separate pieces of glass that join together to form the repeated patterns do not match exactly in color; the tones are intentionally used somewhat at random. This diverts the eye from undue emphasis on the pattern designs and gives—without the eye knowing why—an impression of individual workmanship . . . enhanced by the removal at irregular intervals, especially in the darker places, of small patches of color, exposing completely or partially the plain glass surface. Thus a defused effect to light and color is gained.

When Charles Connick died in 1945 the New York Times wrote that he was “considered the world’s greatest contemporary craftsmen in stained glass.” In Pittsburgh from about 1905 to 1907, Connick worked as manager of Rudy Brothers. There he supervised George Sotter and Lawrence Saint, who became leaders in the next generation of American Gothic glass artists. Howard Gilman Wilbert of Pittsburgh spent some time at the Connick Studio in Boston after World War I. In the 1930s, Connick invited a gifted teenager, Rowan LaCompte, to visit the Connick Studio; he provided council and encouragement to an artist, now 84, known for his great Rose window, and other windows, at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. At Connick’s death, his employees inherited the Studio he had led for 32 years. The men and women Connick had trained operated the studio as Connick Associates until 1986, 41 years after his death. Charles Connick’s American Gothic windows, and the windows of those he trained and influenced, continue to surprise, delight, and inspire.

Photographs of stained glass windows © 2008 and text © 2009 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

Illustrations

1. First Baptist Church

2. Façade window

3. Chancel window section

Architectural Criticism,” Architecture 26:4 (October 15, 1912), 186.

Arthur G. Byne, “First Baptist Church Pittsburgh Pa.,” Architectural Record 32:3 (September 1912), 208. Arthur Byne (1883-1935) was an authority on Spanish architecture and decorative arts; he and his wife Mildred co-authored numerous books in this field.

Robert A. Scott, The Gothic Enterprise: A Guide to Understanding the Medieval Cathedral (Berkeley, CA, 2003), 109-110.

Lawrence Lee, George Seddon, and Francis Stephens, Stained Glass (New York, 1976), 72.

Barry Bergdoll, “The Ideal of the Gothic Cathedral in 1852,” A. W. N. Pugin: Master of Gothic Revival (New Haven, 1995), 103.

James L. Sturm, Stained Glass From Medieval Times to the Present: Treasures to Be Seen in New York (New York, 1982), 13.

Ernest E. Logan, The Church That Was Twice Born: A History of the First Presbyterian Church of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1773-1973 (Pittsburgh, 1973), 13.

Michael Botwinick, “Foreword,” in Richard Guy Wilson, et al, The American Renaissance 1876-1917, (New York, 1979), 7.

Artists who worked at both the Chicago Fair and The Library of Congress (LOC) include muralist Edwin Blashfield, muralist Kenyon Cox (who has a stained glass window in Pittsburgh’s Third Presbyterian Church), painter Gari Melchers, painter William De Leftwich Dodge, sculptor Daniel Chester French, painter Elmer Ellsworth Garnsey (who also worked at the Carnegie Library, Pittsburgh), sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens (who designed the Magee Memorial at the entrance to the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in 1908), sculptor Frederick W. MacMonnies, sculptor Philip Martiny, painter Carl Melchers, painter Herman Schladermundt (who did the 1907 stained glass windows and skylight in Pittsburgh’s Rodef Shalom), and sculptor Francois Tonetti-Dozzi. French, Garnsey, A. Saint-Gaudens, and Martiny also worked on the Boston Public Library. The architects of the LOC were John Smithmeyer and Paul Pelz, who designed the Carnegie Library of Allegheny. The stained glass in LOC was fabricated by Heinigke & Bowen of New York who had windows in the R. B. Mellon residence in Pittsburgh and the Henry R. Rea residence in Sewickley (both gone). John White Alexander who worked at LOC also painted the murals in the 1907 entrance to The Carnegie.

Pierce Rice, “The Thomas Jefferson Building as a Work of Art,” in John Y. Cole and Henry Hope Reed, eds., The Library of Congress, (New York, 1997), 74.

Mrs. John A. Logan, Thirty Years in Washington (1901), quoted in Cole/Reed 1997, 66.

Julie L. Sloan, “The Rivalry Between Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge.” Nineteenth Century 17:2 (Fall 1997), 30.

Helene Barbara Weinberg, “The Early Stained Glass Work of John La Farge (1835-1910) Stained Glass 67:2 (Summer 1972), 10.

Cecilia Waern, John La Farge, Artist and Writer, The Portfolio: Monographs on Artistic Subjects with Many Illustrations (London, 1896), 68.

For a description of La Farge’s three windows at The Presbyterian Church, Sewickley, see Albert M. Tannler, “Shedding Light on Some New Old Windows,” PHLF News 171 (October 2006), 16.

Roger Riordan, “American Stained Glass.” Pts. 1-3. American Art Review (Boston) 2 (April 1881), 229-234; (May 1881), 7-11; (June 1881), 59-64.

“Dedication of the New Third Presbyterian Church, Pittsburgh.” Presbyterian Banner, November 5, 1903: 17

John Calvin and Thomas Wright worked for La Farge beginning in 1880. They formed their own firm c. 1885 and continued to make glass for La Farge.

Amelia Peck and Carol Irish, Candace Wheeler: The Art and Enterprise of American Design, 1875-1900 (New York, 2001), 38.

Riordan, “American Stained Glass” [Montgomery reprint 1889], 607.

Julie Sloan 1997.

S. Bing, Artistic America, translated by Benita Eisler and introduced by Robert Koch (Cambridge, MA, 1970), 147. See also Gabriel Weisberg, Art Nouveau Bing: Paris Style 1900 (New York, 1989).

Cecelia Waern, “The Industrial Arts of America: The Tiffany Glass and Decorative [sic] Co., ” The Studio 11:52 (August 1897), 161.

Waern, “Industrial Arts,” 162.

Waern, “Industrial Arts,” 157-158.

Waern, “Industrial Arts,” 158.

Waern, “Industrial Arts,” 162.

Martin Eidelberg, “Tiffany and the Cult of Nature,” Masterworks of Louis Comfort Tiffany. [1989] (New York, 1993), 88.

Hugh McKean, The “Lost” Treasures of Louis Comfort Tiffany (Garden City, NJ, 1980), 83.

Martin Eidelberg, Nina Gray, and Margaret K. Hofer, A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll and the Tiffany Girls (New York, 2007), 12.

Eidelberg, et al, A New Light, 12.

Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company exhibited at the1898 Pittsburgh A.I.A. Chapter Exhibition. Exhibits included one window designed by Frederick C. Church, a collection of Favrile glass, and cartoons and sketches for windows designed by Elihu Vedder, J. A. Holzer, Mary E. MacDowell, Howard Pyle, Frederick Wilson, L. C. Tiffany, Edward P. Sperry, F. C. Church, and Joseph Lauber. [33] Two of the Sperry sketches were for windows at Calvary Methodist Church and one of the Wilson cartoons was for the window he designed in First Lutheran Church. Tiffany’s firm did not participate in any of the later architectural exhibitions in Pittsburgh.

Sturm, Stained Glass, 43. One should note that Sturm’s book is not without error; it is also out-of-print.

Mia Fineman, “Looks Brilliant on Paper But Who, Exactly, Is Going to Make It?” New York Times, 7 May 2006. Emphasis added.

For example George F. Bodley, William Burges, William Butterfield, J. L. Pearson, Anthony Salvin, George Gilbert Scott, J. P. Seddon, George Edmund Street, Alfred Waterhouse, and others.

Antoinette F. Downing and Vincent J. Scully, Jr., The Architectural Heritage of Newport Rhode Island 1640-1914, 2nd rev. ed. (New York, 1982), 22.

Isabelle Anscombe and Charlotte Gere, Arts and Crafts in Britain and America (London, 1978), 84.

Alan Crawford,” United Kingdom: Origins and First Flowering,” The Arts and Crafts Movement in Europe and America: Design for the Modern World 1880-1920, edited by Wendy Kaplan (Los Angeles, 2004), 26.

William Morris, “Glass, Painted or Stained.” From Chambers’s Encyclopaedia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge, V, 246-248, in Morris on Art and Design, edited by Christine Poulson (Sheffield, 1996), 45.

A. C. Sewter, The Stained Glass of William Morris and His Circle (London, 1974), 21.

Morris, “Glass, Painted or Stained,” 44.

Peter Cormack, “A Truly British Movement,” Apollo (April 2005), 49.

Crawford, 2004, 31.

Christopher Whall, Stained Glass Work (London/New York, 1905), 82. See also Peter Cormack, The Stained Glass Work of Christopher Whall 1849-1924 (Boston, 1999).

Whall, 84.

Whall, 94.

Whall, 268.

Whall, 238.

Some architects: E. Donald Robb, who worked on First Baptist, and later formed the firm that completed the National Cathedral; [Francis] Allen & [Charles] Collens and Charles Maginnis of Boston; John Corbusier of Cleveland, Charles Z. Kauder of Philadelphia; and John T. Comes, his associates Leo McMullen and William Perry, and William P. Hutchens, Edward J. Weber, and Carlton Strong of Pittsburgh.

Albert M. Tannler, Charles J. Connick: His Education and His Windows in and near Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, 2008), 82.

I am grateful to Janice Chadbourne, Curator, Fine Arts Department, Boston Public Library who drew my attention to this file.

Charles J. Connick to Edwin J. van Etten, November 15, 1933; Calvary Episcopal Church Archives.

Connick, “Stained and Painted Glass,” 82.

My thanks to Peter Cormack who provided a copy of this letter.

James McFarlan Baker, American Churches, Vol. 2, Illustrated by the Work of the New York Office of Cram, Goodhue & Ferguson (New York, 1915), 8.

“Symbols of the Interior: The Windows,” [William E. Lincoln,] The First Baptist Church of Pittsburgh (Boston, 1925), 60-63.