Louis Bellinger and the New Granada Theater

By Albert M. Tannler, Historical Collections Director (1991-2019)

Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

Numbers may speak more forcefully than words. In 1930 there were 22,000 white architects in the United States. The number of black architects?—60. One of them was Louis A. S. Bellinger of Pittsburgh.

Louis Arnett Stuart Bellinger (1891-1946) was born in Sumter, South Carolina and was educated in Charleston. He attended Howard University, concentrating on mathematics and engineering (among his other subjects were Latin, Greek, and German), and was graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in 1914.

After college he married. His wife, Ethel, was two years younger and a native of New Jersey.

Bellinger became a mathematics teacher, first in Florida, then in South Carolina. World War I interrupted his teaching career and he served part of 1917 as a Lieutenant in Training Company 2, 17th Provisional Training Regiment, before returning to the classroom.[1]

In 1919 the Bellingers moved to Pittsburgh and Louis began an architectural career here.[2] His major commission was designing Central Park, home field of the African-American Pittsburgh Keystones baseball team in 1920, at the request of team owner, Alexander m. Williams.[3] In 1922 he rented a downtown office at 525 Fifth Avenue across from the Allegheny County Courthouse, took out a listing in the Yellow Pages, and debuted in the “Contracts to be Awarded” section of The Builders’ Bulletin as the architect of a house to be built in Greenfield. That house and an apartment building on Junilla Street in the Hill District are his first recorded architectural designs in Pittsburgh; their precise location, whether they were built, or, if so, whether they still stand, is presently unknown.

From 1923 to 1926, Bellinger worked as an assistant architect in the office of the City Architect of Pittsburgh.[4] During that time he designed a police station and remodeled service buildings in the city parks. No specific records documenting Bellinger’s work for the city have yet been found, but this position would have given him practical experience in the workings of an architect’s office and useful contacts within city government. He further sharpened his skills by taking a course in advanced construction at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University).

In September of 1926, he returned to private practice with a major commission for a building to be erected, not in Pittsburgh, but in Philadelphia—the now demolished African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Book Concern at 19th and Pemberton Streets.

Early in 1927 Bellinger designed his most important Pittsburgh building. On February 19, 1927, The Builders’ Bulletin announced that plans were being prepared for a building on Centre Avenue in the Hill for the Grand Lodge, Knights of Pythias (Colored). The Knights of Pythias (Colored) was a national fraternal organization dedicated to “‘assuage the sufferings of a brother; bury the dead; care for the widow, and educate the orphan.’ The Colored Knights offered a service that no other late nineteenth-century social organization offered: life insurance.”[5] The organization’s inspiration and name came from the story of the Greek friends, Damon and Pythias; its appellation as a knighthood was based on the medieval concept of chivalry. The Pythian Temple would be the headquarters for the local chapter of the organization as well as provide office and commercial space and recreational and entertainment facilities for the community.

On March 12, 1927, the Pittsburgh Courier formally announced the project and gave details of the interior amenities planned for the building, based on an interview with the architect:

Mr. Bellinger, when interviewed by a Courier reporter, divulged the information that there will be entrances with a lobby decorated in Italian marble with a terrazzo floor.

There will be three commodious storerooms in the first floor, with separate storage cellars. On the Center avenue side, there will also be a banquet and a drill hall with a clear space with 5,000 square feet of drill space. In addition to this, there will be a modern equipped kitchen, a cloak room which can accommodate 2,000 wraps and lavatory facilities.

The second floor will furnish the city with a long-felt want. This floor will contain an auditorium with a gallery, ladies and gentlemen’s lounging rooms, miniature stage with modern footlights, suitable for amateur productions and musical concerts. The auditorium has been so arranged that the floor can be easily converted into a basketball court, with a clear 20-foot floor space of 6,000 square feet. Seating accommodations for 1,500 people have been arranged. The auditorium will be decorated in classical style, with myriad lights, finished walls, box seats, hardwood floor and a new innovation in seating arrangement. Entrance to the gallery will be through a fireproof foyer. Several modern office suites will complete this floor.

On the third floor there will be five lodge rooms, with the latest sound-proofing acoustical methods and several suites of business offices.[6]

The construction contract was awarded to Hodder Construction Company of Braddock and construction began in June 1927. Bellinger served as construction manager. Approximately nine months later, on March 25, 1928, the completion of the building was celebrated.

The Pythian Temple—dramatically sited on a crest of Centre Avenue as it curves past Devilliers Street—is built on the hillside between Centre and Wylie Avenues. The Centre Avenue front is the principal façade. Bellinger gave the fraternal knighthood a four-story brick and terra cotta structure decorated in the late English Gothic style known as Tudor. Below the crenellations at the top we find polychromatic terra cotta coats-of-arms. Projecting bands of molding with foliaged tips are laid in vertical strips across the facade and bent into flat-topped frames around the store windows on either side of the main entrance. The store windows and the grand arched entrance adorned with Tudor flowers had transoms inset with textured glass panes or prisms, popular in display windows since the 1890s.

The Wylie Avenue side, at the top of the hillside and across the street from Ebenezer Baptist Church, is narrower, three-stories high, and constructed of patterned brick. Over the arched center doorway is the inscription, “Pythian Temple A.D. 1927.” Originally there were shops on the first floor and offices above.

The Knights of Pythias presented public exhibitions of quasi-military drill team exercises. Hence the need for a 5,000 square foot drill hall (that could be converted into a banquet hall). The second-floor auditorium, with its innovative seating arrangement that allowed the space to be used as a basketball court, was, according to the Courier, “a long-felt want.” It immediately became the community showplace, attracting nationally known black entertainers to Pittsburgh.

While the Pythian Temple was under construction, Bellinger participated in the first major exhibition of the work of African-American artists in the United States, sponsored by the Harmon Foundation and held in New York City, January 5-15, 1928.[7] He exhibited a “Proposed Plan for Church and Apartments.” (This may have been a design for the Ebenezer Tabernacle at Hemans and Addison Streets.)

During the late 1920s Bellinger designed several houses, including a duplex for Ethel and himself (they had no children) at 530 Francis Street; an apartment building for the Prince Hall Temple Association on Centre Avenue; an office, store, and apartment building for Mutual Real Estate Co. at Wylie and Morgan; remodeled an older home into a store and apartments in Hazelwood; and remodeled St. Mark A.M.E. Church in Wilkinsburg and Rodman Street Baptist Church in East Liberty.

In 1926 Bellinger had considered running for the state legislature.[8] In 1932 he ran unsuccessfully for Congress as a Republican candidate from the 32nd Congressional district; he was the only African-American among the five candidates.[9]

His major architectural work during the 1930s was Greenlee Field, home of the Crawford Grays. The Courier reported: “When completed this park, which promises to be the mecca of the Hill district sport and amusement lovers, will have a capacity of 6,000.”[10] Greenlee Field opened on April 28, 1932. It was demolished in December 1938; public housing was erected on the site. [11]

Bellinger’s only other recorded jobs between 1931-36 were an apartment building on Centre Avenue and a store room remodeling on Wylie. A commission to design a new church for the Sixth Mt. Zion Baptist Church in Lincoln/Larimer was cancelled (they bought a nearby building). The duplex on Francis Street was sold. Louis gave up his downtown office; Ethel gave music lessons at home, which supplemented their income. There were professional disappointments. Bellinger’s drawing of a Proposed Masonic Temple for the 1933 Harmon Foundation exhibition was damaged in transit and couldn’t be displayed.

Although the Pythian Temple auditorium was flourishing—in 1932, for example, a Duke Ellington concert before a live audience of 3,000 was broadcast nationwide—by 1936 the Knights of Pythias were no longer able to contribute to the mortgage on the Temple. Pittsburgh architect Alfred M. Marks prepared plans to convert the building into a commercial theatre. A movie theater was installed in the former first floor drill hall/banquet room; the second floor auditorium became the venue for live music and community events. On May 20, 1937, now sporting a polychromatic Art Moderne first floor marquee, the Pythian Temple reopened as the New Granada Theatre.

By this time, Bellinger had taken a leave-of-absence from the private practice of architecture, and had become an inspector with the City Bureau of Building Inspection. Except for an unsuccessful attempt to reopen his practice in 1940, Bellinger worked as a City building inspector from 1937 to 1942.

His return to private practice began slowly. The only documented commission prior to 1945 was a church basement in Hazelwood. In 1945, however, Bellinger was working on several projects out of the house he and his wife rented at 3171 Centre Avenue: remodeling a house into African-American Legion Post 27 in Fairmont, West Virginia; expanding the Iron City Lodge Post 17 on Centre Avenue; remodeling the Crunkelton funeral home in Manchester; remodeling Johnson’s Photography Studio on Centre Avenue; designing a new house for photographer Luther Johnson. Ethel was now teaching music at Robert L. Vann Elementary School.

On February 3, 1946, Louis Bellinger died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage. He was 54 years old. His career in architecture and the building industry in Pittsburgh had continued for over a quarter of a century. His death was noted in The Builders’ Bulletin, Pittsburgh Courier, Pittsburgh Press, and Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.[12]

He was buried in Allegheny Cemetery; his gravesite is directly up the hill from the grave of baseball player Josh Gibson. On January 27, 1947, the Pittsburgh Chapter of the American Institute of Architects observed a moment of silence in memory of two members deceased the previous year—one was Louis Bellinger.

References to Louis A. S. Bellinger are found in Negro Artists: An Illustrated Review of Their Achievements (New York: Harmon Foundation, 1935), Theresa Dickason Cederholm, Afro-American Artists: A Bio-bibliographical Directory (Boston Public Library, 1973), and Who Was Who in American Art 1564-1975 (Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1999). A detailed account of his life and work appears in African-American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary 1865-1945 (New York: Routledge, 2004).[13]

What you won’t find easily are his buildings. Less than half-a-dozen buildings are known to have survived and all have been changed, in some cases drastically. All that remained of his home on Francis Street in 2003 was a fragment of the green glazed-tile fireplace from the first-floor apartment. Even the house he rented at 3171 Centre Avenue is gone, though its neighbors remain.

In 1995 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation lent the Hill Community Development Corporation $99,000 to purchase the New Granada. It was not until the end of 2008 that serious restoration work began. By 2009 funds from The Heinz Endowments, and commitments from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Budget Office Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program and the Allegheny County Economic Development, Community Infrastructure and Tourism Board were received/promised to Landmarks who acted as fiscal agent for the Hill CDC and supervised the $1.1 million stabilization effort. African-American architect Milton Ogot directed the work of Repal Construction Company and Brace Engineering in masonry restoration, roof replacement, and other stabilization efforts including securing façade masonry and removal of the 1937 marquee to safe storage.

Because of its local and national significance, the Pythian Temple/New Granada is being nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. Events that took place there, from 1928 through 1970, were featured in the Courier, an all-black weekly newspaper distributed worldwide, with a circulation of 250,000 in 1938. The New Granada is a property associated with African-American culture and American jazz history. It is a memorable place as the cultural center of Pittsburgh’s African-American community; Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Lena Horne, Billy Eckstine, Cab Calloway, and other noted musicians performed there in person and on film; and it is the major work of Pittsburgh’s first African-American architect.

Revised and adapted from Albert M. Tannler, “Louis Bellinger: Pittsburgh’s African-American Architect,” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review Focus 28:14 (February 9, 2003), 8-10. Text ©2010 Albert M. Tannler and Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation.

Select Bibliography

Louis Arnett Stuart Bellinger

“Local Man Appointed to City Architect’s Office: L. A. Bellinger Gets Position as Designer After Waiting for 11 Months.” Pittsburgh Courier, 11 August 1923: 2.

“Chosen for Their Works of Art.” Pittsburgh Courier, 21 January 1926: A7.

“Bellinger’s Campaign is Strengthened.” Pittsburgh Courier, 8 May 1926: 4.

“Local Architect Out For Congress.” Pittsburgh Courier, 12 March 1932, 1; “Bellinger Planning Campaign,” Pittsburgh Courier, 26 March 1932, 1; “Bellinger Submits Record,” Pittsburgh Courier, 2 April 1932, 6; “Bellinger Polls Over 6,000 Votes,” Pittsburgh Courier, 30 April 1932: 1; “L. A. S. Bellinger Thanks Voters,” Pittsburgh Courier, 7 May 1932: 7.

“Greenlee Ball Park Preps for Opener,” Pittsburgh Courier, 9 April 1932: 7.

Harmon Foundation. Negro Artists: An Illustrated Review of Their Achievements. New York: Harmon Foundation, 1935: 43.

“Louis A. S. Bellinger.” The Builders’ Bulletin 30:24 (February 9, 1946): 1.

“Louis A. Bellinger, Architect, Buried.” Pittsburgh Courier, 9 February 1946: 1.

Cederholm, Theresa Dickason. Afro-American Artists: A Bio-bibliographical Directory. Boston: Boston Public Library, 1973: 22.

Fields, Mamie Garvin, and Karen Fields. Lemon Swamp and other places: A Carolina Memoir. New York: The Free Press, 1983: 12.

Reynolds, Gary A. and Beryl J. Wright et al. Against the Odds: African-American Artists and the Harmon Foundation. Newark, NJ: Newark Museum, 1989: 284.

Falk, Peter Hastings, ed. “Louis A. S. Bellinger.” Who Was Who in American Art 1564-1975. Madison, CT: Sound View Press, 1999: Vol. 1: 271.

Tannler, Albert M. “Louis Bellinger: Pittsburgh’s African-American Architect.” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review Focus 28:14 (February 9, 2003): 8-10.

Tannler, Albert M. “Louis Arnett Stewart [sic] Bellinger (1891-1946).” African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary 1865-1945. Edited by Dreck Spurlock Wilson. New York: Routledge, 2004: 30-32.

Brewer, John M., Jr. African Americans in Pittsburgh. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2006: 52.

Strecker, Geralyn M. “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field: Biography of a Ballpark.” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal 2:2 (Fall 2009): 37-67.

2007-2013 Centre Avenue:

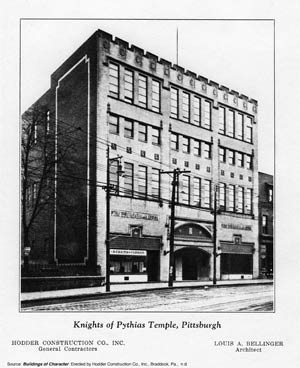

“Knights of Pythias Temple, Pittsburgh.” Buildings of Character Erected by Hodder Construction Co., Inc., Braddock, Pa. Braddock: Daily News Herald, n.d.: [20].

The Builders’ Bulletin 11:25 (February 19), 11:43 (June 25) 1927.

“K. of P.’s to Erect $300,000 Temple; Drawing of Architect Approved.” Pittsburgh Courier, 12 March 1927: 1, 8.

“Insurance Maps of Pittsburgh Pennsylvania.” Vol. 1. New York: Sanborn Map Company, 1927: Plate 43.

“Many Witness Corner-Stone Laying of Pythian Temple.” Pittsburgh Courier, 31 March 1928: 11.

“Pythians Invade City: Collier Heads Throng—Keystone Knights Here For Annual Conclave; Dedicate New Temple.” Pittsburgh Courier, 21 July 1928: 1.

Reid, Ira DeAugustine. Social Conditions of the Negro in the Hill District of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: General Committee on the Hill Survey, 1930: 80, 95.

“Duke in National Broadcast from Temple on Monday.” Pittsburgh Courier, 2 January 1932: 1.

“Ellington is Presented with Courier Loving Cup; Record Crowd Out: King of Jazz Hugs Mother as Trophy is Presented; Largest Crowd Ever to Witness Affair in Attendance at Pythian Temple Ballroom.” Pittsburgh Courier, 9 January 1932: 1.

The Builders’ Bulletin 21:9 (October 31), 21:11 (November 14), 21:13 (November 28), 21:16 (December 19): 1936.

“Huge Crowd Turns Out for Opening of New Granada Theater.” Pittsburgh Courier, 22 May 1937: 1.

“What’s The Old Granada Theatre Doing in the Same Neighborhood With The New Phoenix Mall?” Pittsburgh Courier, 3 June 1978.

Brown, Eliza Smith, et al. African American Historic Sites Survey of Allegheny County. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1994: 147, 148.

Bolden, Frank E., Laurence A. Glasco, and Eliza Smith Brown. A Legacy in Bricks and Mortar: African-American Landmarks in Allegheny County. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 1995: 54-55.

Kidney, Walter C. Pittsburgh’s Landmark Architecture: The Buildings of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 1997: 324.

Palm, Kristin. “The Jazz Messenger: A Boarded-up Theater in Pittsburgh’s Hill District Holds the Key to Community: Collective Memory.” Metropolis, February 2001.

Rawson, Christopher, and Laurence A. Glasco. August Wilson: Pittsburgh Places in His Life and Plays. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation (forthcoming 2010).

Photos:

1. “Knights of Pythias Temple, Pittsburgh.” Buildings of Character: Erected by Hodder Construction Co., Inc., Braddock, Pa., n.d.

2. New Granada with Art Moderne marquis, Frank Stroker, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation ©2007.

3. Cornice detail – terra cotta coat of arms, Frank Stroker, Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation ©2007.

We thank Julie Hodder and Lu Donnelly for providing a copy of the Hodder Co. brochure. The author also thanks Joy Barnes, Henry Bellinger, Lu Donnelly, Geri Strecker, and Louise Sturgess for their assistance.

[1] He was proud of his military service, however brief; the details are inscribed on his grave marker.

[2] In “Bellinger Submits Record” (April 2, 1932), the Pittsburgh Courier reported that Bellinger “practiced architecture in Philadelphia in 1916, going from there to teach mathematics at Allen University, Columbia, S.C., 1916-17.”

[3] McDondald Williams, Ph.D., “The Pittsburgh Keystone 1921-22: Proposal for Placement of State Historical Marker at Site of Central Amusement Park,” submitted May 2011 to the Pennsylvania Historical Museum Commission.

[4]“ Local Man Appointed To City Architect’s Office,” Pittsburgh Courier, 11 August 1923, 2.

[5] Michael Tow, “Secrecy and Segregation: Murphysboro’s Black Social Organizations, 1865-1925,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (Spring, 2004), 58-59. See http://findarticles.com/.

[6] “K. of P.’s to Erect $300,000 Temple; Drawing of Architect Approved.” Pittsburgh Courier, 12 March 1927, 1, 8.

[7] Harmon Foundation. Negro Artists: An Illustrated Review of Their Achievements (New York: Harmon Foundation, 1935), 43. See also Gary A. Reynolds and Beryl J. Wright et al., Against the Odds: African-American Artists and the Harmon Foundation. (Newark, NJ: Newark Museum, 1989), 284.

[8] “Bellinger’s Campaign Is Strengthened,” Pittsburgh Courier, 8 May 1926, 4.

[9] “Local Architect Out For Congress,” Pittsburgh Courier, 12 March 1932, 1.

[10] “Greenlee Ball Park Preps for Opener,” Pittsburgh Courier, 9 April 1932, A5.

[11] Geralyn M. Strecker, “The Rise and Fall of Greenlee Field: Biography of a Ballpark.” Black Ball: A Negro Leagues Journal 2:2 (Fall 2009), 37-67.

[12] After Louis’ death, Ethel Bellinger moved to Philadelphia; she later remarried.

[13] Albert M. Tannler, “Louis Arnett Stewart [sic] Bellinger (1891-1946).” African American Architects: A Biographical Dictionary 1865-1945, edited by Dreck Spurlock Wilson (New York: Routledge, 2004), 30-32. My text, as submitted to the editor, noted that the New Granada Theater “survives but is endangered” and it was described in the supplementary list of Bellinger commissions and buildings as “altered.” The editor chose to declare the building “demolished.” He also changed the spelling of Stuart to “Stewart.”