Category Archive: Essays

-

Mary Elizabeth Tillinghast (1845-1912), New York

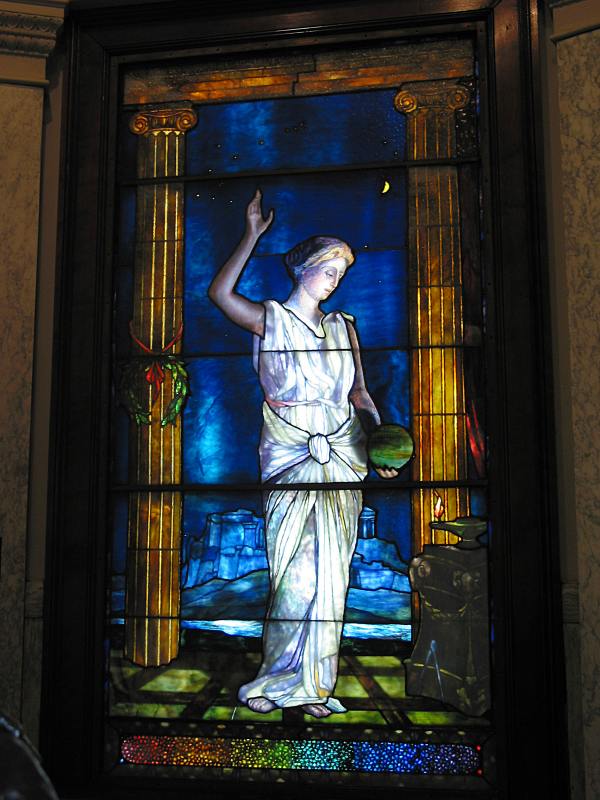

Mary Elizabeth Tillinghast (1845-1912), New York: Urania, 1903, Allegheny Observatory; T. E. Billquist, architect

Photographs and text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

The Allegheny Observatory, established in 1859 and given in 1867 to Western University of Pennsylvania (later the University of Pittsburgh), hired architect T. E. Billquist to design a new building on a more advantageous site in 1899. Billquist’s American Renaissance observatory is a scientific acropolis—a tan brick and white terra cotta hill-top temple whose Classical forms and decoration symbolize the unity of art and science. At the core of the building is a small rotunda, housing an opalescent glass window depicting Urania, the Greek muse of astronomy.

Director Frank L. O. Wadsworth, of the observatory of the Western University of Pennsylvania, announced last evening the arrival of a stained glass window from New York as the gift of the Misses Smith, who have devoted a generous sum to the establishment of the observatory. Prof. Wadsworth says the window is to adorn the new structure of the observatory. It is pronounced one of the most artistic works of Miss Mary E. Tillinghast.

The window, which is 9 x 3 feet, shows Urania, almost lifelike, standing in an open porch. Her garb is of the ancient Grecian fashion; in one hand she holds a planet, the other being raised to the heavens. Beside her resting against a pedestal is a pair of compasses; on the pedestal is the lamp of knowledge, whose flames lighten the figure. She stands between two columns. Around one is a wreath of laurel.

Far behind her, in the moonlight, are the ruins of the Acropolis. Shining in the sky and placed relatively with astronomical precision are the moon, the evening star, planets of Pleiades. Under the figure is a delicately blended spectrum, typifying the work of the observatory.

Pittsburgh Post, 3 July 1903

The donors were well-to-do philanthropic siblings, Jane Smith (1832-1911) and her sister Matilda (1837-1909), enthusiastic supporters of the University. The artist was Mary Elizabeth Tillinghast (1845-1912) of New York City. Like many American artists of the period, she spent several years in Europe, visiting Italy and studying painting in Paris. One of her teachers, Emile-Auguste Carolus-Duran, also taught the most famous American painter of the era, John Singer Sargent.

In 1878 Tillinghast began a seven-year affiliation with New York artist John La Farge (1835-1910)—painter, muralist, critic, and inventor of a new process for making decorative glass windows. Tillinghast became an expert textile designer, served as manager of the La Farge Decorative Art Company, and learned the art of designing and making windows from La Farge.

La Farge patented his opalescent window glass in 1880: “The object of my invention is to obtain opalescent and iridescent effects in glass windows . . . softening the light, and, by reason of its unevenness of structure and formation [prevent] the direct passage of rays of light.” La Farge claimed that his glass had the “great advantage as to realistic representation of natural objects.” This new glass was known at the time as “American Glass.” Barbara Weinberg notes that La Farge developed it in order to “reconcile the color and brilliance of early glass with contemporary desires for naturalistic form . . . , to permit depiction of rounded forms and convincing space.” American Renaissance painters admired the spatial realism introduced by Raphael and 15th-century Renaissance painters, and sought to emulate it—in paintings and in glass windows.

Tillinghast’s first major window, Jacob’s Dream, was installed in 1887 in Grace Episcopal Church, New York City. She worked from her Greenwich Village studio, primarily as a window designer, but she also designed furniture and, in one case, was architect, decorator, and glass artist for a private chapel. Her glass was exhibited and won gold medals at several World’s Fairs. In addition to church windows, she designed windows for residences, and for institutions, most notably Urania in Pittsburgh and The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1908) in the New York Historical Society.

The year before Tillinghast’s Urania was installed in the Observatory, Fortune by La Farge was installed in D. H. Burnham’s Frick Building in downtown Pittsburgh; both windows portray female figures framed by Classical columns—decorative art echoing the Classical architecture of the building.

The Allegheny Observatory was the first major Pittsburgh building by Thorsten E. Billquist (1867-1923). Billquist was born in Sweden and studied at the University of Gothenburg. He arrived in the United States in 1887 and appeared in Pittsburgh in 1893. Little is known about his activities during this six-year period, but he is said to have worked on the Boston Public Library for McKim, Mead & White, the firm most closely identified with the American Renaissance. In Pittsburgh, Billquist spent a year as a draftsman with Longfellow, Alden & Harlow, then another year in the office of W. Ross Proctor, an early graduate of Columbia University’s Beaux-Arts-derived curriculum. He practiced from 1897 to 1923; from 1905 to 1909 in partnership with Edward B. Lee, who had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Billquist is best known for elegant Colonial Revival and Neo-Classical residences in Pittsburgh’s East End.

Sources: “Window for Western Observatory,” Pittsburgh Post, 3 July 1903. “Woman Stained Glass Artist: Mary Tillinghast’s Work in Pittsburgh and Other Cities.” Pittsburgh Post, 15 July 1906. H. Barbara Weinberg, “John La Farge and the Invention of American Opalescent Windows,” Stained Glass 67 (Autumn 1972): 4-11; and “The Early Stained Glass Work of John La Farge (1835-1910),” Stained Glass 67 (Summer 1972): 4-16. L. A. Richards, “An Unworthy Obscurity,” Stained Glass 89 (Spring 1994): 35-41, 51-52. Albert M. Tannler, “‘Temple of the Skies’: Observatory Hill Renaissance of Art and Science,” Pittsburgh Tribune-Review Focus 30:15 (February 13, 2005): 8-10.

Illustrations

- Allegheny Observatory

- Urania

-

Henry Hunt (1867-1951)

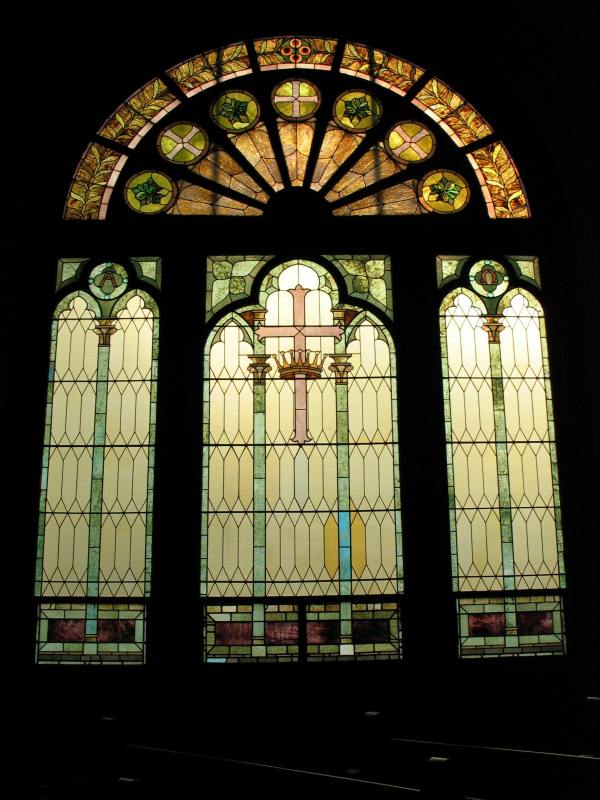

Henry Hunt (1867-1951) for Leake & Greene (1889-1906), Pittsburgh: Window, 1895-96, Hawthorne Avenue Presbyterian Church, Crafton, Pa.; Boyd & Long, architects

Photographs and text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

Peripatetic in arrival and swift and enigmatic in departure best characterizes the firm of Leake & Greene. Theodore H. Leake (b. 1859) was working as a “draughtsman” in Boston 1886 through 1888; in 1889 he and George Greene (1862-1935) established the decorating firm of Leake & Greene at 78 Boylston Street. Neither apparently had training in stained glass (both list their occupation during the next decade as interior decorators) and they soon hired glass artist Henry Hunt (1867-1951), recently arrived from London, who had learned the glass craft from his father.

In 1890 we find the firm in Pittsburgh; in 1891, Leake & Greene are back in Boston and advertising their services as “stained glass and decorators.” In 1893 the firm returned to Pittsburgh and the partners commissioned a house on Church Lane in suburban Shields (now a part of Edgeworth, Pa., along the Ohio River) attributed to Longfellow, Alden & Harlow, an architectural firm founded in 1886 with offices in Boston and Pittsburgh. It is likely—albeit educated speculation—that the decorators knew the architects and through them discovered Pittsburgh. (Longfellow, Alden & Harlow affably dissolved itself in 1896 with Alexander Longfellow taking over the Boston work while Frank Alden and Alfred Harlow remained in Pittsburgh.)

Leake & Greene’s earliest documented surviving windows are in Hawthorne Avenue Presbyterian Church, which opened in 1896 in Crafton, Pa., four miles southwest of Pittsburgh. The windows, commissioned August 3, 1895, are simple yet colorful windows, with floral decoration and Gothic columns framing a cross-and-crown motif. Such simplicity is often found in Presbyterian church windows of that period. Intriguingly, the Hawthorne windows resemble to a degree the aisle windows in H. H. Richardson’s Emmanuel Episcopal Church (1884-86), which probably date from the 1890s. Frank Alden supervised construction of Emmanuel and designed its parish house in 1887. In 1897, Alden & Harlow added three bathrooms to Henry Clay Frick’s home Clayton and two buildings on the grounds. Leake & Greene designed the glass.

Emmanuel Church is the site of Henry Hunt’s finest known work for Leake & Greene, the Thaw Memorial reredos of 1898, an Italian Romanesque tour-de-force in glass mosaic, with decorative metal and stonework supplied by Richardson’s master carver, John Evans of Boston. The cartoon was exhibited at the first architectural exhibition held in Pittsburgh in 1898, and a section, “Adoring Angels,” illustrated in the catalog. Leake & Greene also exhibited five other Pittsburgh projects, including a stair window for Alden & Harlow’s Jennings residence and a nave window (not executed) for the Church of the Ascension, designed by the late William Halsey Wood, but constructed by Alden & Harlow.

Leake & Greene did not participate in the next two architectural exhibitions, but they were a strong presence in the third exhibition, held in 1905. In addition to windows for Alden & Harlow’s Armstrong residence and the chapel at St. Margaret’s Hospital in Pittsburgh (both gone) and Trinity Episcopal Church, Bellevue, Pa. (current status unknown), the majority of the commissions were for sites in New York state.

The firm is last listed in Pittsburgh city directories in 1906. That year Hunt established his own firm (still in business as Hunt Stained Glass Studios). Leake & Greene exhibited glass at the Architectural League of New York, February 4-24, 1906, but their entry, “St. John and St. Paul,” was designed by New York artist Tabor Sears. The firm’s last documented Pittsburgh commission, awarded February 8, 1906, was the glass in Greenstone United Methodist Church, Avalon, Pa., designed by architects Vrydaugh & Wolfe.

By 1910 Greene had married and listed his occupation as stained glass artist. Leake still called himself a decorator. For a time, Leake and George and Leonora Greene shared the Church Lane residence. Leake drops from view and Greene continued to work in stained glass; in 1923 he designed a window for the Homewood Cemetery chapel, fabricated by Rudy Brothers. Green (he dropped the “e”) was living on Church Lane, sans wife, at the time of his death in 1935.

Nothing is currently known about A. C. Boyd and J. A. Long, the architects of Hawthorne Presbyterian Church. They only appear in the 1895 Pittsburgh city directory.

Sources: Hawthorne Presbyterian Church of Crafton, Pa., Minutes, Inception 1894-May 1901. “George Green.” [sic] Sewickley Herald, 13 December 1935. Henry Hunt, “The Autobiography of Henry Hunt,” Stained Glass 36 (Winter 1941): 118-122. Albert M. Tannler, “A Visit to Boston,” PHLF News 163 (February 2003): 14-15. Information and documentation from Marilyn Evert, Homewood Cemetery. Additional information from Mary Beth Pastorius and Kirk Weaver.

Illustrations:

- Hawthorne Presbyterian Church, Crafton, Pa.

- Hawthorne window

- Aisle windows, Emmanuel Episcopal Church, dates unknown; attributed to Leake & Greene

- “Adoring Angels,” Emmanuel Episcopal Church, 1898 (detail)

-

Ludwig Grosse (1862-1917), Pittsburgh

Ludwig Grosse (1862-1917), Pittsburgh: Robert S. Johnston Memorial, 1892, Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd, Hazelwood; William Halsey Wood, architect

Photographs and text copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation

Most of the finer productions in stained and mosaic glass used in this country were imported from Europe, principally from Munich and other cities in Bavaria. Of late years, however, notable progress has been made in this branch of art in the United States, until a high degree of excellence has been reached.

“The L. Grosse Art Glass Co.”

History and Commerce of Pittsburgh and Environs (1894)Ludwig Grosse is remembered, if at all, for bringing William Willet to Pittsburgh in 1897; Willet served as art director of Grosse’s firm 1897-98, before establishing his own studio here in 1899. While researching Willet’s career, Joan Gaul found that Ludwig Grosse was born in 1862 in Munich, Germany, attended the Munich Academy, arrived in Pittsburgh in 1888, and died in 1917.

An 1894 description of Grosse’s firm in a commercial directory and listings and advertisements in city directories give us glimpses of Grosse’s activities in Pittsburgh. He established himself as “an artist in stained glass” in 1889, worked for the prominent Pittsburgh glass firm of S. S. Marshall & Brothers in 1890, acquired their downtown facility and opened The L. Grosse Art Glass Company there in 1891; the company continued under his name through 1898. In 1899 and 1900 he is listed as a dealer in “art works.” Grosse appears to have left Pittsburgh thereafter.

The list of Grosse’s stained glass commissions in the 1894 commercial directory is invaluable: Four windows for St. Paul’s Cathedral (designed by Charles Bartberger, trained in Germany like many Civil War-era architects in Pittsburgh); mausoleum windows for the McCune and Pollard families; and residential glass for Thomas Jenkins in Allegheny City and S. S. Bloch in Wheeling, West Virginia. Old St. Paul’s and the Jenkins residence are gone, and I have been reliably informed that the mausoleums are not in the Allegheny or Homewood Cemeteries. There are other cemeteries to be explored, as is the house in Wheeling, but no extant glass by Ludwig Grosse in Pittsburgh had been found—until I read in The Bulletin, October 29, 1892:

The dedicatory services of the Protestant Episcopal Church of the Good Shepherd, Hazelwood . . . will take place tomorrow morning . . . . The inside is beautifully frescoed and the windows, made from designs by Mr. Ludwig Grosse, of this city, are both handsome and artistic. One of them is the gift of Mrs. Simon Johnston in memory of her son whose death occurred less than a year ago.

The clue came, as have so many, from the work of the late James D. Van Trump, Pittsburgh’s preeminent architectural historian and Landmarks’ co-founder. Jamie created an index to articles pertaining to architecture that appeared in The Bulletin from 1887 to 1927. His notation, “Windows by Ludwig Grosse of Pittsburgh,” sent me to The Bulletin article and the identification of the Johnston Memorial. (This discovery was the impetus for scanning Jamie’s index to create a finding aid to The Bulletin now available in the Landmarks Library.)

Ludwig Grosse was trained in Munich, a center for the production of stained glass and religious decorative art, supported by Ludwig I and shaped aesthetically by an association of German artists, The Brotherhood of St. Luke. These artists, also known as “the Nazarenes,” were inspired by early Renaissance portraiture. Sarah Brown writes in Stained Glass (1992): “The work of the Nazarenes was characterized by a religious idealism combined with a style derived from that of Dürer, Raphael, and Perugino.” When Grosse arrived in Pittsburgh in 1888, he found a kindred artistic environment. Although American glass artists were using a new material—opalescent window glass, invented by American painter John La Farge, that was made by blending opaline (milk glass) with molten colored glasses—and not the traditional hand-blown antique glass used elsewhere, the prevailing aesthetic in the United States favored glass windows imbued with the idealized naturalism found in Renaissance paintings.

The Johnston Memorial uses American opalescent glass in a manner that both American and German glass makers of the time would have found congenial. It is the only window known to be by Grosse, pending further documentation. (The Mary Burgwin Memorial chancel window, the Hill Burgwin Memorial in what is now the Baptistery, and a damaged window after Holman Hunt’s Light of the World might be his work as well.)

The Church of the Good Shepherd, Hazelwood (1891-92), ranks among Pittsburgh’s most significant church buildings. It is the second of three buildings in metropolitan Pittsburgh designed by William Halsey Wood of Newark, New Jersey (1855-1897), an architect of great promise—Ralph Adams Cram called him “a man of genius”—who died at the age of 41. Wood also designed the Carnegie Library in Braddock, 1888; and the Episcopal Church of the Ascension in Pittsburgh, 1896, noteworthy for glass by Healy & Millet of Chicago and furnishings and decoration by J. & R. Lamb Studios of New York.

Sources: The Bulletin 25, 29 October 1892: 19. History and Commerce of Pittsburgh and Environs (New York 1894): 83, 219. Pittsburgh city directories 1889-1900. Sarah Brown, Stained Glass: An Illustrated History (London 1992): 134. Joan Gaul, “Pittsburgh 1893-1912: Five Artists,” The Journal of Stained Glass 28 (2004): 49. Thanks to David J. Vater and Sue Weigand of Wheeling, WV, for research assistance.

Illustrations

- Church of the Good Shepherd – exterior

- Church of the Good Shepherd – interior

- Robert S. Johnston Memorial

-

Alfred Godwin (1850-1934), Philadelphia

Alfred Godwin (1850-1934), Philadelphia: Harvest window, 1883?/1892 and

Library window 1892, Clayton, Henry Clay Frick residence; Andrew W.

Peebles (1882) and F. J. Osterling (1890-92), renovation architectsText and photograph of Library window copyright © 2007 Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. Photograph of Clayton © 1998 William Rydberg PHOTON for Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation. Photograph of Harvest by Pytlik Design Associates copyright © 2006 Frick Art & Historical Center.

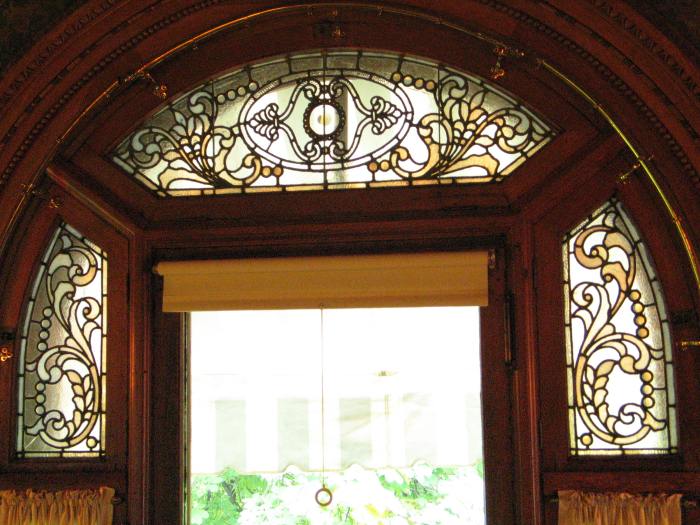

In 1882 Henry Clay Frick purchased Homewood, an Italianate house in Pittsburgh’s East End. He hired Pittsburgh architect Andrew W. Peebles to supervise extensive remodeling, and D. S. Hess & Company of New York provided fashionable furniture and interior appointments. Eighteen ornamental glass windows designed and made by Alfred Godwin & Company of Philadelphia were installed in 1883: the principal window in the stairway landing, Love in the Tower; transom windows; vestibule door windows; parlor and library windows containing figures and landscapes; and a “Window Rear Hall (with figure).” Jean Farnsworth tells us that Godwin, of Manchester, England, arrived in Philadelphia in 1870. By 1882 he had established his own glass firm, and although he closed his shop in 1916 he remained active in Philadelphia well into the 1930s.

In 1890 Frick hired Pittsburgh architect Frederick J. Osterling to transform the house into a grand French château, Clayton. The enlargement/renovation was completed in 1892. Some of Godwin’s 1883 glass was retained and remounted in the remodeled interior. The figure window, Harvest, made of hand-blown (known as “antique”) and enamel-painted glass may be the window originally located in the rear hall; it received an opalescent frame. A letter of January 2, 1892, from Frick’s secretary, George Megrew, to Godwin notes that Godwin had “not sent the glass panel called ‘Harvest’ for the sliding door. Please let me know about it immediately.” A work order dated January 22, 1892, noted “ornamental work ordered added to figure for sliding door in hall”; the work was approved by F. J. Osterling on January 25, 1892.

Frick’s great-granddaughter Martha Sanger describes Harvest:

For the door between the entrance hall and kitchen quarters, A. Godwin & Company of Philadelphia, known for using semiprecious stones in stained-glass windows, provided a small golden-hued panel framed in moonstones that depicts a woman dressed in blue, holding an overflowing cornucopia.

Godwin also provided bathroom windows for Mrs. Frick and her sister Martha Childs and four three-light glue-chip or “crystalline” windows for the Library.

The Pittsburgh firm of Leake & Greene provided the opalescent glass dome and ornamental cabinet doors in Mr. Frick’s new bathroom of 1897, designed by Alden & Harlow. Godwin’s Love in the Tower was removed from the stairway (only two panels have survived and may be seen in the Frick Art Museum) when Cottier & Company of New York redecorated the house in 1903-04 and installed an antique glass Cottier window, The Four Virgins.

Windows by Alfred Godwin in Pittsburgh are especially noteworthy since Godwin played a significant part in the training of two of Pittsburgh’s leading glass artists. According to Joan Gaul, J. Horace Rudy (1870-1940) was an apprentice in Godwin’s firm 1891-1892; the period that the Clayton windows were reinstalled. In 1893, Rudy, his parents and his brothers, arrived in Pittsburgh and established Rudy Brothers Company. Rudy is important, not only for the high quality of his own work, but for his training of some of the most important American glass craftsmen of the next generation, notably Charles J. Connick (1875-1945), George W. Sotter (1879-1953) and his wife, Alice Bennet Sotter (1883-1967), and Lawrence B. Saint (1885-1961). Before William Willet (1867-1921) moved to Pittsburgh to join The L. Grosse Art Glass Company, he worked for Godwin c.1894-96. Willet’s work helped reshape the approach of the next generation of American glass artists to the glass craft in this country.

Sources: Alfred Godwin catalogues, c. 1883, c. 1890, and 1895, Athenaeum of Philadelphia and the Rakow Library, Corning, New York. “Alfred Godwin,” Stained Glass 29 (Spring/Summer 1934): 54. Helene Weis, “Some Notes on Early Philadelphia Stained Glass,” Stained Glass 71 (Spring 1976): 24-27. Jean Farnsworth, “Biographical Sketches of Stained-Glass Studios and Selected Artists,” Stained Glass in Catholic Philadelphia (Philadelphia 2002): 435-436, 456. www.philadelphiabuildings.org. Information and documentation from Robin Pflasterer, Frick Art & Historical Center. Helen Clay Frick Foundation-Henry Clay Frick Papers, Frick Art Reference Library, New York. Clayton: The Pittsburgh Home of Henry Clay Frick; Art and Furnishings (Pittsburgh 1988). Martha Frick Symington Sanger, The Henry Clay Frick Houses: Architecture, Interiors, Landscapes in the Golden Era (New York 2001): 22. 28. Joan Gaul, “Pittsburgh 1893-1912: Five Artists,” The Journal of Stained Glass 28 (2004): 47. Special thanks to Rona H. Moody and Nicholas Parrendo.

Illustrations:

- “Clayton” (1998)

- Harvest

- Library windows

-

Places Around Pittsburgh: Architecture in Spite of Everything

Frank Lloyd Wright and an admirer, Bruno Zevi, were in front of Santa Maria delle Salute in Venice. Wright said, “Bruno that’s a good church.” It had a wooden dome with fake wooden buttresses, it had pediments, it had pilasters. “But Mr. Wright, you don’t like things like this!” “Bruno: that’s a good church!” The old Shady Avenue Presbyterian Church mixes Romanesque of the homeliest description with Queen Anne, and has a marquee suitable for an apartment house on a rather clumsy wing, but the whole complicated composition somehow muddles through to a charm that could never have been attained in cold blood or with inhibiting clarity of thought.

Frank Lloyd Wright and an admirer, Bruno Zevi, were in front of Santa Maria delle Salute in Venice. Wright said, “Bruno that’s a good church.” It had a wooden dome with fake wooden buttresses, it had pediments, it had pilasters. “But Mr. Wright, you don’t like things like this!” “Bruno: that’s a good church!” The old Shady Avenue Presbyterian Church mixes Romanesque of the homeliest description with Queen Anne, and has a marquee suitable for an apartment house on a rather clumsy wing, but the whole complicated composition somehow muddles through to a charm that could never have been attained in cold blood or with inhibiting clarity of thought.—Walter C. Kidney

-

Places Around Pittsburgh: Façade in Your Face

Fourth Avenue still contains a few “swagger banks,” with facades contrived to give a small-but-O-My! impression even though the properties are diminutive. One of these is Number 337, now the Pittsburgh Engineers’ Building, once the Union Trust Company, a work of 1898 by D. H. Burnham & Co.

Fourth Avenue still contains a few “swagger banks,” with facades contrived to give a small-but-O-My! impression even though the properties are diminutive. One of these is Number 337, now the Pittsburgh Engineers’ Building, once the Union Trust Company, a work of 1898 by D. H. Burnham & Co.Now, street architecture downtown in any case is very likely to strut its lithic stuff, make a grand display despite the drab structural facts, and in this regard a swagger bank is not to be left behind. But 337’s facade is most frankly a work of fictive architecture, a gratuitous composition shoved well out from the glazing line. A Grecian Doric temple stands on a thin imitation of a rusticated basement with a lot of batter. The order is in antis, and the antae are set against the granite-faced end walls, which rise above the pediment to terminate in antefixes (antephiges?) and go back to a little-detailed pediment-like feature that echoes the real pediment. The whole composition has one door and eight window openings, and the front as a whole keeps the weather out somehow, but it is panache that spent the money—wisely and functionally in its own way.

—Walter C. Kidney

-

Places Around Pittsburgh: A Detail

The Conestoga Building stands at Wood Street and Fort Pitt Boulevard, a work of about 1890 by Longfellow, Alden & Harlow. It has a steel frame within solid masonry walls, and its ground-floor openings have a detail that is enlivening in an almost subliminal way. The openings are squarish, and are shaped at the upper corners by little corbels flush with the picked-sandstone facing. The corbels and the lintel they help carry are not plausible as masonry bearing elements, but look good. The shaping of the corbels is particularly subtle. From bottom to top, they go out horizontally, go upward in quarter-rounds, then vertically. The edges begin right-angled, turn into quarter-rounds, then finish as right angles again. A quiet but well-considered modulation.

—Walter C. Kidney

-

Places Around Pittsburgh: A Moderate-Income Fantasy Life

When you live in a building element that takes the form of a tower, you can imagine yourself in a castle if you wish—if you can keep objectivity at bay. A party-wall castle with a front porch, after all, merely suggests a dwelling with identity problems. But on Alpha Terrace in East Liberty, a row of quasi-chateaux faces a row of quasi-Queen Anne villa—the fantasies going only a few inches deep. But the whole thing works out pretty well. This block of Beatty Street has won the hearts of the people, and is now a City Historic District.

When you live in a building element that takes the form of a tower, you can imagine yourself in a castle if you wish—if you can keep objectivity at bay. A party-wall castle with a front porch, after all, merely suggests a dwelling with identity problems. But on Alpha Terrace in East Liberty, a row of quasi-chateaux faces a row of quasi-Queen Anne villa—the fantasies going only a few inches deep. But the whole thing works out pretty well. This block of Beatty Street has won the hearts of the people, and is now a City Historic District.